Abstract

This paper analyses the impact of financial crises on the Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating poverty. To do so, we develop an adjusted Multidimensional Poverty Framework (MPF) that includes 15 indicators that span across key poverty aspects related to income, basic needs, health, education and the environment. We then use an econometric model that allows us to examine the impact of financial crises on these indicators in 150 countries over the period 1980–2015. Our analysis produces new estimates on the impact of financial crises on poverty’s multiple social, economic and environmental aspects and equally important captures dynamic linkages between these aspects. Thus, we offer a better understanding of the potential impact of current debt dynamics on Multidimensional Poverty and demonstrate the need to move beyond the boundaries of SDG1, if we are to meet the target of eradicating poverty. Our results indicate that the current financial distress experienced by many low-income countries may reverse the progress that has been made hitherto in reducing poverty. We find that financial crises are associated with an approximately 10% increase of extreme poor in low-income countries. The impact is even stronger in some other poverty aspects. For instance, crises are associated with an average decrease of government spending in education by 17.72% in low-income countries. The dynamic linkages between most of the Multidimensional Poverty indicators, warn of a negative domino effect on a number of SDGs related to poverty, if there is a financial crisis shock. To pre-empt such a domino effect, the specific SDG target 17.4 on attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies plays a key role and requires urgent attention by the international community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The adoption of UN 2030 agenda for sustainable development, crystallised in 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets, is one of the most important decisions that has been taken in the pursuit of socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. Yet, the whole SDGs endeavour has been based on the assumption that the global economy would be steadily ‘moving forward’. Developing countries were anticipated to grow on average at 5 percent, between 2015 and 2030 (UN 2013), while the target for least developed countries was even higher at 7 percent per annum (SDG 8: target 8.1).

Neither developing nor least developed countries have reached the anticipated growth rates in any single year since 2015. Especially, least developed countries have lagged significantly behind, with average growth for 2015–2018 at 4.2% (WB databank). Furthermore, over the last decade, global debt has been rising in all sectors across the globe (Antoniades and Griffith-Jones 2018). These dynamics are especially pertinent in the low-income developing countries (LIDCs),Footnote 1 which are the priority target of SDGs. Debt has risen significantly in the great majority of LIDCs over the last years, and now 40 percent of these countries (i.e. 24 countries) are already in debt distress or face a high risk of debt distress (up from 21 percent in 2013) (IMF 2018a). The rise of debt is not necessarily a negative development. Indeed access to funding is a prerequisite for economic development (Cecchetti et al. 2011; Antoniades and Griffith-Jones 2018). But the magnitude of debt distress problems currently experienced by LIDCs threatens the successful implementation of SDGs. This is not only an issue for LIDCs. Across 126 developing countries, debt repayments have increased by 60 percent between 2014 and 2017 and are now at the highest level since 2004 (Jubilee Debt Campaign 2018). This means that an increasing percent of the income of developing countries is not directed towards investments that will help them meet the SDGs, but towards servicing their debt. In some cases, the magnitude of this burden can hardly be overstated. According to UNCTAD (2018: 5) ‘in poorer economies, interest payments as a percentage of government revenue more than doubled from 5.7 percent in 2008 to 14 percent in 2017 and to 18.5 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, reaching as much as 30 percent of tax revenue in some sub-Saharan economies’.

The recently attempted monetary normalisation in the US and the EU has significantly exacerbated these negative debt dynamics in developing economies. Increases in the US dollar and Euro interest rates were accompanied by disinvestment from developing countries, leading to their currency devaluation (see BIS 2018). The numbers are staggering: 79 percent of developing countries’ total debt (i.e. both public and private, including financial institutions) is denominated in US dollar and 13 percent in Euro; only 4 percent is denominated in local currencies (authors’ calculation based on BIS 2018 statistics). As a result, developing countries’ treasuries, corporations, banks and households have to pay higher interest rates with local currencies the value of which in many cases has collapsed. Historically these conditions lead to currency and/or bank crises followed by sovereign debt crises and defaults.

These adverse dynamics are exacerbated by the fragile and deteriorating condition of the global economy. In recent annual reports, the IMF (2019) refers to a ‘weakening global expansion’ and the World Bank (2019) to ‘darkening skies’. Both institutions refer to a number of headwinds against the weak recovery experienced by the global economy after the 2007/08 global economic crisis. These headwinds include tightening financial conditions, trade tensions, increased geopolitical uncertainty, reduced resilience, and, as already noted, high levels of public and private debt. The slowdown in growth in developed economies raises also concerns about the donors’ will and ability to honour their commitment for increasing development funding; a sine qua non factor for meeting the SDGs.

Although international organisations have recently shifted their attention to the effects of existing debt dynamics in the implementation of the SDGs (e.g. IMF 2018a; UNCTAD 2018; UN 2018), analyses that attempt to quantify the implications for different SDGs and to assess knock-on effects between them are still missing. In this context, this paper focuses on poverty and has a dual aim. First, we develop a comprehensive framework that allows us to study in an integrated way the aspects of poverty that are dispersed in different SDGs. This is important as aiming to eradicate monetary poverty without addressing poverty’s multiple social, economic and environmental facets is unlikely to succeed. To do so, we propose an adjusted Multidimensional Poverty approach that allows us to bring together monetary, basic needs, health, education and environmental aspects of poverty.

Second, we bring the existing global debt context ‘back in’ in the analysis of SDGs by offering new estimates on its impact on poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon. We do not mean this primarily as an exercise in numbers or costing. Having concrete estimates on how existing debt dynamics impact on different dimensions of poverty, in different groups of countries, help us understand better the mode of interaction, feedback loops and dynamic linkages between these different poverty dimensions in conditions of financial distress. This is an important piece in the jigsaw of rethinking and hopefully improving the implementation strategy regarding the eradication of poverty in the current global economic context. To produce these new estimates, we use a large dataset of more than 400 past financial crisis episodes, across the globe, over the period 1980–2015. Our data are not constrained in sovereign debt default episodes, but include currency crises (significant depreciation of local currencies vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar), as well as banking crises that require significant policy intervention measures by governments. Thus, we attempt to capture most of the parameters that define the global debt context of SDGs implementation.

Our analysis proceeds in the following way. First, we present our adjusted Multidimensional Poverty approach that includes aspects of income, basic needs, education, health, and environment. Then, we present our data sources and modelling strategy that aim to assess the impact of financial crises on Multidimensional Poverty. Finally, we present and discuss our findings. Based on the latter, we conclude that current debt dynamics are making the attainment of SDGs in most LIDCs unfeasible. This is a problem that will not go away unless decisive action is taken from the side of the creditors. Therefore, activating debt sustainability management tools, included in SDG 17, should become a priority, if the SDGs are to remain on track, especially in LIDCS, and the gains made with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are to be maintained.

Multidimensional poverty in the SDGs framework

A number of recent studies has pointed to the fact that if no significant action is taken now, the SDGs will not be met by a wide margin (e.g. Chandy et al. 2013; Schmidt-Traub 2015; Manuel et al. 2018; Development Initiatives 2013, 2018). For instance, Chandy et al. (2013) using a consumption-based model estimate that the number of people in extreme poverty in 2030, in their baseline scenario, will be 342 million (cited in Development Initiatives 2013), while under benign conditions (best case scenario) this could fall to 100 million and in adverse conditions (worst case scenario) it could rise to 1.04 billion. Similarly, Manuel et al. (2018) project that if growth continues at past rates the number of people in extreme poverty will be halved in comparison to 2015, which means that 400 million people will still live in poverty. This corresponds with updated projections reported by the Development Initiatives (2018) that point to a margin between 200 (best case) and 400 (worst case) million people still in poverty by 2030. Furthermore, the available studies point to an increasingly greater concentration of poverty in low-income countries (54 percent of global total according to Manuel et al. 2018) and in sub-Saharan Africa (50 percent of global total according to Development Initiatives 2018), i.e. those areas and populations that are in greater danger of being ‘left behind’.

Yet, the experience from the earlier UN Millennium Development Goals programme (2000–2015) has taught us that meeting a nominal poverty or funding target is not enough to reach those most in need or address the causes that perpetuate extreme poverty. It is unlikely that extreme poverty itself will be eradicated if we increase people’s income to more than $1.90 a day, because extreme poverty is a multidimensional condition of deprivation rather than an amount in dollars. Put differently, without employing new integrated frameworks of analysis and supporting new arrangements and practices that address the sources of poverty in developing countries (and beyond), SDGs will not meet their aim of eradicating poverty regardless of the amount of money poured into meeting nominal poverty targets (Clemens et al. 2007; Devarajan 2015).

Moving beyond extreme poverty headcount indicators and including more poverty dimensions and their inter-related nature is therefore a precondition for developing effective strategies to tackle global poverty. Yet, there is no easy way to tackle the overlapping and co-determining nature of SDGs. Sachs et al. (2019) suggest to operationalise SDGs, by organising them into six sets of transformation: (1) education, gender, and inequality; (2) health, wellbeing, and demography; (3) energy decarbonization and sustainable industry; (4) sustainable food, land, water, oceans; (5) sustainable cities and communities; and (6) digital revolution for sustainable development. In a similar manner, Schmidt-Traub (2015) has suggested to approach SDGs as eight ‘investment areas’. But these suggestions diffuse rather than integrate the different aspects of the phenomenon of poverty.

A different approach would be to prioritise the conceptualisation of poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon. The contribution of the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) designed and launched in 2010 by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Report Office (HDRO) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) is critical here. The MPI attempts to capture poverty in terms of deprivation in three key aspects of living: health, education, and living standards. Therefore, it generates unique insights in what ways are different people poor and ‘how people themselves experience poverty in multiple and simultaneous ways’ (UNDP 2019; Alkire and Santos 2010; Alkire et al. 2011). In this way, MPI not only goes beyond an income-based definition of poverty, but also offers a framework to integrate different SDGs in analysing poverty as a social rather than a monetary phenomenon. For as analysis on Multidimensional Poverty has demonstrated, people may not fall into the $1.90 category of extreme poverty, but may still experience extreme poverty in terms of health (nutrition and child mortality), education (years of schooling and school attendance) and living standard (access to water, sanitation, electricity, housing, cooking fuel and asset ownership) (see Alkira and Sumner 2013). Therefore, a Multidimensional Poverty approach offers a more effective analytical tool on poverty, better placed to assist the global SDG strategy to eradicate poverty. Table 1 presents the ‘architecture’ of the Multidimensional Poverty Framework (MPF).

Our paper builds on the Multidimensional Poverty Index by integrating in the same framework income and non-income based definitions of poverty as well as aspects of environmental poverty. The need to incorporate environmental and natural resources aspects in MPF is an issue raised by OPHDI itself, which has developed the MPI (see especially OPHI 2016; Thiry et al. 2018). Of course, both the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (M.E.A 2005) and now the SDGs encourage such an integrated approach to poverty alleviation, wellbeing and sustainable environmental management. Existing literature points to trade-offs between poverty and the environment and the need for decisions in alleviating poverty to be taken with explicit consideration for environmental and ecological trade-offs (Uitto 2016; Schreckenberg et al. 2018). For instance, intensification of agriculture or timber production may help lifting groups out of poverty, but will likely have adverse, unsustainable effects on natural habitats and biodiversity. Conversely, converting managed landscapes to natural or protected environments may in some cases be done without considering local communities relying on this natural capital (Fairhead et al. 2012). Yet, by integrating environmental indicators in our poverty analysis, we want to advocate that environmental damage is not a trade-off to poverty alleviation, but a critical and integral aspect of poverty itself. Our adjusted Multidimensional Poverty Framework is presented in Table 2.

Our proposed adjusted MPF consists of five dimensions of poverty and 15 indicators that cut across SDG 1 (poverty), SDG 2 (hunger), SDG 3 (health and wellbeing), SDG 4 (education), SDG 6 (water and sanitation), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG 9 (industry, innovation, infrastructure), SDG 11 (sustainable cities), SDG 13 (Climate action), SDG 15 (life on land). Wherever possible, we used official SDG targets for our indicators. Wherever this was not possible, due to lack of effective official indicators or available long-term data, we consulted the existing literature so as to identify alternative proxy indicators (see Table 2). In constructing this adjusted MPF, our aim is not to create a ‘new index’. Our decision on indicators to be included was not based on ‘ideal indicators’, but on indicators for which long time-series data are available. Building on MPF, our main aim was to construct a methodological framework that allows indicators for different aspects of poverty to productively come together in the context of SDGs. This is a necessary step for analysing the differential impact of financial crises on key aspects of living that define the phenomenon of poverty as well as how this differential impact matters for meeting or missing the key sustainable development goal of eradicating poverty.

In the next section, we present our data and empirical strategy in studying the relationship between financial crises and Multidimensional Poverty.

Data sources and rationale

For the 15 indicators in our adjustment Multidimensional Poverty Framework, we use secondary unbalanced data from 150 countries for the period of 1980–2015. These data are sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank (The World Bank 2018b), CCI satellite data imaging available in Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) dataset (Food and Agriculture Organization 2018) and the Environment Performance Index (EPI)-Yale (Wendling et al. 2016, 2018). The unbalanced dataset used in this study is due to different starting date of data availability and missing data in the indicators and control variables used. Regarding different starting date, data for some indicators are available from 1980, whilst others are only after 1990 or 2000. As a result, econometric analysis of indicators and income groups is performed on different numbers of observations. Table 2 presents the 15 Multidimensional Poverty indicator used and their sources. Table 2 also presents which of these indicators are official SDG indicators and which ones are used as proxy to capture aspects of poverty falling under different SDGs.

For our analysis, we further divide the 150 countries in our dataset into four income groups based on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita as per the World Bank Atlas Method (The World Bank 2018a). The number of countries per income group is presented in Table 3.

Our data on global financial distress events are based on Laeven and Valencia (2018). Initially published as part of an IMF working paper, the Laeven and Valencia dataset is one of the most comprehensive datasets available, covering financial crises at global level during the period 1970–2017. The dataset includes three types of financial crises: systemic banking, currency, and sovereign debt crises. Banking crises are defined as systemic, when two conditions are met: there are significant signs of financial distress in the banking system (e.g. bank runs, bank liquidations, significant losses in the banking system in terms of non-performing loans or total assets) and significant banking policy interventions in response to banking losses (e.g. deposit freezes, bank nationalizations, substantial public liquidity support or guarantees). Currency crises are defined as a nominal depreciation of the country’s currency vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar of at least 30 percent that is also at least 10 percentage points higher than the rate of depreciation in the year before. As for sovereign debt crises, these include episodes of sovereign default or debt restructuring. It is important to mention that approximately 58 percent of the crises in the dataset have a duration of 3 or more years, whilst the most frequent duration in the dataset is that of 5 or more years (approximately 37 percent of the total). Thus, we are not only focusing on the break-out year of crises, but on their continuous effects throughout their duration. The database includes 151 banking crises, 236 currency crises and 75 sovereign debt crises; of these 41 are twin crises (banking and currency) and 11 triple crises (banking, currency, sovereign debt). The most frequent type of crisis in high-income countries is that of banking crises, whereas for middle- and low-income countries is currency crises. All income groups have experienced all three different types of crises, giving us room for comparison between crisis and non-crisis years.

In this paper, we are less interested in the different sources of financial distress. Our main concern is to estimate how financial crises, regardless of specific types, impact on poverty dynamics in different groups of countries. Such an approach serves also better our panel data statistical approach (see below). Thus in our analysis, we aggregate all types of crises into one categorical variable, namely financial crisis. Out of 5400 total observations, 651 periods are characterised by a financial crisis, while 4749 periods are ‘crisis-free’. A positive sign to the financial crisis categorical variable means that the events of financial crises are associated to higher magnitude of poverty indicators relative to the absence of financial crises and vice versa.

Modelling the impact of financial crises on multidimensional poverty

This paper investigates the association between financial crisis events in different countries with each of the 15 Multidimensional Poverty indicators. This is intended to capture the influence of financial crises on poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon and as a result on the attainment of key SDGs related to poverty. This method of using a categorical variable in capturing event responses has been frequently used (see for instance Barkema et al. 1996; McGahan and Mitchell, 2003; Makino et al. 2004; Afonso et al. 2010; Papi et al. 2015; Widiarto et al. 2017). Thus, our focus herein is whether the financial crisis events exhibit statistically significant association with a change in time series of the poverty indicators used in our framework.

To deal with the multiplicity and diversity of poverty indicators included, we adopted an econometric approach of general-to-specific (GETS) modelling. In GETS, empirical model building starts with a general statistical model, which includes all potential regressors based on existing theories, then it is reduced by removing the statistically insignificant variables. This step was accompanied by continuous validity checking at every step, until our model arrived to a simplified final form with all significant regressors (see for instance Hoover and Perez 1999, 2004; Hendry and Krolzig 2004). The literature used in the modelling of different indicators is presented in Table 2.

In evaluating the association of financial crises to poverty indicators and the attainment of selected SDGs, we utilize generalized least square random effects panel data econometric modelling. Separate models are developed for each poverty indicator, where each indicator is specified as the dependent variable. The financial crisis influence is set as a categorical variable of interest, controlling for several economic indicators based on existing studies (see Table 2).

If the Multidimensional Poverty indicator of interest in country i in time t, as dependent variable, can be denoted as \({\text{MPI}}_{it}\) (\(i = 1, \ldots ,n; \,t = 1, \ldots ,T),\) thus, the reduced form of the model for global region can be written as follow:

whereby \(\beta_{0}\) is the regression intercept; \(X_{ijt}\) represents the independent variable X (\(j = 1, \ldots ,k\)) for country i in time t; \(\beta_{j}\) represent coefficients for independent variable j (\(j = 1, \ldots ,k\)); \(\gamma_{1}\), \(\gamma_{2}\) and \(\gamma_{3}\) are coefficients for three categorical variables representing lower-middle, upper-middle and high-income countries (that are compared against low-income countries); \(\gamma_{4}\) is coefficient for categorical variable representing a financial crisis event, \(u_{it}\) captures between-entities (in this case between-countries) error, whilst \(e_{it}\) signifies within-entities (within-countries) error.

In line with Eichengreen et al. (2017), this study assumes that there are inherent differences in economic growth characteristics between countries in different income groups. Moreover, in the event of financial crisis, the assumption herein is that low-income countries are affected more than middle- and high-income countries (see Harper 2009). Thus, to permit the impact of a financial crisis to vary across income groups, and thus capture the ‘income group effect’ in poverty dynamics (Eichengreen et al. 2017), we run our model (1) for each income group separately (i.e. low-income, lower-middle income, upper-middle income and high-income countries). To preserve uniformity, these four sub-models are constructed with the specification used in global model with reduced form that can be written as follow:

Random effect panel data are chosen in the analysis for three reasons: firstly, as it is expected that between-countries variation influences the dependent variables, i.e. the differences across countries have some influence in the attainment of poverty indicators (Lee et al. 2018). Random effects modelling captures this cross-sectional variation, i.e. variation between-countries in each year, in addition to time-series variation, i.e. within-countries variation, along the period observed. Secondly, implementing random effects panel data modelling enables us to observe the influence of time-invariant variables, i.e. income groups, to poverty indicators. Finally, random effects modelling provides more flexibility in observing possible curvilinear relationships between poverty indicators and their explanatory variables. This curvilinear relationship is indeed significant in one of income-based indicators of poverty used, i.e. the poverty gap at US$1.90 a day poverty line.

Our models incorporate Huber/White or sandwich estimator to obtain heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (see Huber 1967; White 1980; Freedman 2006). To test the overall significance of the models, a Wald F-test is first run along with the regression analysis. This test shows that all coefficients from our regression results are statistically significant. A Breusch–Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test is also performed to assess the use of random effects panel data regression (using generalized least squares) in comparison to ordinary least squares regression (which includes fixed effect panel data regression). The results show that the random effects are appropriate to be used in the models as the variance between-countries is significant. The results of Wald F-Test are included with complete regression results in Electronic Supplementary Material S1–S14, whilst the results for Breusch–Pagan tests are included in S15.

Results: financial crises and poverty dynamics

The results of our panel data econometric modelling are presented in Table 4. Financial crises events are observed to have statistically significant relationships with most Multidimensional Poverty indicators. The results point to several negative synergies between different indicators of deprivation in the event of financial crises. Furthermore, our econometric estimates generally point to significant differences between different income groups, with low-income countries being more severely affected by financial crises in most cases. Financial crisis events are generally showing the expected statistically significant association with our Multidimensional Poverty indicators stated in column 2 of Table 4. Yet, counterintuitive results are found on two indicators (access to safe drinking water and infant mortality rate). Using the framework of Multidimensional Poverty approach, we present the findings of our analysis below.

Income

Financial crises exhibit statistically significant correlations to deteriorated measures of both poverty headcount (breadth of poverty) and poverty gap (depth of poverty). At global region crises are associated with a higher poverty headcount of 2.05% and a larger poverty gap of 1.20%, ceteris paribus. The correlation between crises and aspects of income-based poverty is extended to all income groups, but the differences between them are striking. The most important result in this regard is the magnitude of the coefficients in the case of low-income countries, where crises are associated with 9.89% higher poverty headcount and a 9.82% wider poverty gap. Thus, these countries in times of financial crises, not only see significant numbers of people falling below the $1.90 a day extreme poverty line, but also see the conditions of people already in extreme poverty to significantly deteriorate. A pronounced but smaller impact on poverty headcount (6.75%) is also observed in lower-middle income countries, although, in these countries we find no statistically significant relation with regard to poverty gap. The reverse is the case for upper-middle income countries, where financial crises are associated with an increase of 1.05% in poverty gap, but not with a higher poverty headcount. Finally, financial crises are associated with negative developments in both poverty headcount and poverty gap in high-income countries at 0.29% and 0.17%, respectively.

Our results point to a more pronounced effect of financial crises on income-based poverty than existing results in the literature (see Chen and Ravallion 2010; Ravallion and Chen 2009). The strong and statistically significant effect of financial crises on low-income countries is particularly worrying. Considering the high number of low-income countries in high risk or already in debt distress, meeting SDG1 on eradicating extreme poverty is a huge challenge that requires urgent action, if the target is not to be missed from our generation’s time horizon.

Basic needs

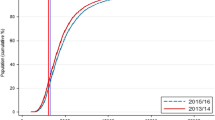

Our results on the association between financial crises and access to drinking water, basic sanitation and electricity are not uniform. At global region, financial crises are found to be significantly correlated with a reduced access to basic sanitation and electricity, by 0.5% and 1.79%, respectively, ceteris paribus, but we find no significant correlation with regard to access to drinking water. At income group level the picture is mixed. The reduced access to basic sanitation in the global region is driven by the statistically significant reduced access to basic sanitation in the lower-middle income countries of 0.81%, while we find no statistically important relationship for the other groups. Financial crises are associated with significantly lower access to electricity in the low and lower-middle income countries, at 5.28% and 2.93%, respectively, while no significant effect is found for upper-middle and high-income countries. Finally, counterintuitively, financial crises appear to be associated with reduced access to basic drinking water only in high-income countries, at 1.16%, whereas this association appears to be positive in low-income countries. Our positive result here may reflect the overall continuous positive trend of increased access to basic drinking water in low-income countries (see Fig. 1), rather than a positive impact of financial crises on drinking water. This may also be the reason why no significant relationship is found between crises and basic sanitation in low-income countries (Table 4 and Fig. 1).

Health

Our health-related poverty indicators include infant and maternal mortality rates and premature deaths due to exposure to particulate matter pollution. With regard to infant mortality, we find that financial crises are significantly associated with lower global infant mortality rates in lower-middle and upper-middle income countries, whilst no significant association is recorded for low-income and high-income countries. These findings are counterintuitive as they contradict existing country- or region-specific results in the literature. For instance, Rajmil et al. (2014) have found an excess infant mortality rate in sub-Saharan African countries and Filippidis et al. (2017) have found increased infant mortality rate in Greece in 2009, as a result of the economic crisis. Yet the general trend for infant mortality for both global region and each income groups, shows a continuous declining trend (see Fig. 1) and it is this signal that seems to be recorded in our results. With regard to maternal mortality, we do not observe a statistically significant relationship for most income groups. This corresponds with recent findings that stress the general steady improvement in maternal mortality (e.g. Alkema et al. 2016 and WHO 2019). However, we do find a significant effect for low-income countries, where financial crises correlate to higher maternal mortality, on average by 29 deaths per 100,000 live births. This confirms past and recent studies on maternal mortality in low-income countries (e.g. Brenner 1973, Alkema et al. 2016) and highlights the problem of government health expenditure in these countries, especially in periods of economic crisis (Anderson et al. 2011). Our third health indicator refers to premature deaths due to exposure of a country’s population to particulate matter pollution. Although, this indicator estimates the economic costs (‘foregone labour income’) to the national economy due to these premature deaths, we are interested in this as an effective proxy of health damage due to environmental pollution. We find that financial crises are significantly associated with higher economic costs due to particulate matter pollution in global region by 0.16% of GNI, ceteris paribus. This effect in low-income, lower-middle income and upper-middle income countries is 0.37%, 0.13% and 0.06% of GNI, respectively; we find no effect in high-income countries. Note that these results do not capture ‘other’ health effects (not leading to death) and their related huge economic costs (e.g. children respiratory diseases) (see Chen et al. 2017).

Education

Here, we examine how financial crises may affect the out-of-school rates in primary education and government education expenditure. Our results show that financial crises episodes are significantly associated with higher numbers of primary children out of school. At the global level, we estimate the effect at 1.43% and for low-income and lower-middle income countries is 5.80% and 3.13%, respectively, whereas we find no statistically significant results for upper-middle income and high-income countries. With regard to government education expenditure, the magnitude of the effect of financial crises, especially in low and middle income countries, is staggering. Financial crises correspond significantly to lower government education expenditure in the global region, low-income, lower-middle income and upper-middle income countries, by 24.04%, 17.72%, 12.10% and 25.24%, respectively. Thus, financial crises have a severe effect on education-related aspects of poverty, by severely constraining the capacity of developing countries to develop their future human capital.

Our results confirm findings reported by Shafiq (2010) and OECD (2013). Financial crises exacerbate education-related poverty through both macro and micro channels. They force countries to reduce their future human capital investment, whilst, at the same time, they strike households already in poverty or around poverty line, forcing them to pull out the children from primary education; thereby destroying a key route to escape poverty, i.e. education. Lack of education pulls the occasional or churning poor segments of the population (as per Hulme and Shepherd (2003)’s classification) into chronic poverty condition (Kulild 2014).

Environment

Our indicators here aim to capture how financial crises relate to key dimensions of environmental poverty such as CO2 emissions from forest removals and fossil fuels, forest rents, terrestrial protection and agricultural land use. These indicators are very important as they point to the potential overexploitation of a country’s natural capital, reducing ecosystem services. We find that financial crises associate with an increase in net forest land CO2 emissions both in low-income and high-income countries by 0.818 and 2.479 terragrams, respectively. The possible causes for this are multiple and may include an increase in forest product exports from low-income countries (Mills Busa 2013), to household illegal logging (Pagiola 2001; Lekakis and Kousis 2013) and increase in large-scale forestry operations and wildfires in high-income countries (Curtis et al. 2018). Contrary to the increase in net carbon emission due to forest loss during financial crises, at the global level financial crises are significantly associated with an 8.19% decrease in economic costs from CO2 fossil fuel emissions. These results are driven by decreases in lower-middle and upper-middle income countries of 16.88% and 17.89%, respectively; no effect is found in low- and high-income countries. Yet, as existing literature points out the beneficial crisis impact from the reduction in CO2 emissions is rather short term (for a recent review and evidence see Pacca et al. 2020). With regard to forest rents, we find a statistically significant effect only for low-income countries, where forest rents are higher by 0.80%. These results confirm earlier findings from Angelsen and Resosudarmo (1999) and Leahy and Schipani (2018). Financial crises are also observed to be significantly correlated with the reduction of terrestrial protected areas, an important indicator with regard to natural resources rent exploitation and biodiversity protection (Scharlemann et al. 2016). At global level, the reduction is 0.57%. At different income groups level the most pronounced effect is at upper-middle income countries, at 1.05%, followed by low-income countries, at 0.85%.

Finally, a significant association is found between periods of financial crises and decrease in agricultural land in global region and amongst upper-middle income and high-income countries, by 1%, 2.36% and 1.21%, respectively. More research is required to establish the drivers for this decrease in agricultural land, but reasons may include changes in the price of agricultural commodities (Pagiola 2001), while farmers are also faced with higher input costs and poorer output price transmissions (Piesse and Thirtle 2009). Furthermore sustainable diversification and intensification of agricultural land practices may also play a role (for lower income countries see Pretty et al. 2018). In other cases, crises events may cause agriculture to be reduced in favour of manufacturing or industrial plants or the reduction in agricultural land may point to population movements to urban centres, thus uncovering another negative feedback loop of the crises that affect Multidimensional Poverty dynamics.

Income groups’ differences

The income group results in Table 4 are based on our model (2), i.e. we run our model separately for each income group. One of the advantages of using a random effects approach in our modelling is that we can better observe how different income groups influence each other in times of economic shocks, based on the assumption that the performance of each income group is not independent of the performance of the other groups. Thus, we are better placed to establish the significance of group-specific drivers in each of the Multidimensional Poverty indicators. To account for these group-specific effects, we include categorical variables representing income groups, with low-income group as base category. We present the results of this analysis in Table 5.

Our results show that there are significant differences between all four income groups in access to basic drinking water, access to basic sanitation, access to electricity, maternal mortality ratio, governmnet education expenditure, forest rents and terrestrial protected area. In these variables, low-income countries are shown to be significantly lagged behind other income groups. For instance, in the access to basic sanitation, lower-middle, upper-middle and high-income countries are found to have significantly higher access by 8.90%, 21.795% and 22.379% ceteris paribus. In other variables, significant differences are also found between two or three income groups. Our results suggest that an income group-specific effect exists and plays a role in the attainment of most of the poverty indicators in the global region. The magnitude of the gap between low-income and other income groups is significant. If SDGs are to be met for this group of countries in the current context of debt dynamics, thinking out of the box and policies beyond established conventions will be required.

Discussion

Our analysis provides new empirical evidence and estimates on the effect of financial crises on Multidimensional Poverty indicators. As expected, low-income countries are affected more severely than other income groups in most poverty indicators, including the poverty headcount ratio, poverty gap, access to electricity, maternal mortality and children out of school. Considering current global debt dynamics and heightened debt distress risks and episodes across poor countries this means that not only the attainment of the UN Agenda 2030 for low-income countries is beyond reach, but also that instead of steps ahead we may see steps backwards, i.e. a reversal of the positive outcomes achieved during the MDGs.

Yet, focusing only on low-income countries is not enough to understand the challenge posed by financial crises on poverty. For instance, our results show that financial crises have significantly impacted upper-middle income countries more than other income groups, in reduction of government education expenditure, reduction of agricultural land and reduction of terrestrial protected areas. Considering both the area of the planet and the size of global population living in these countries, this demonstrates that Multidimensional Poverty remains a significant challenge for upper-middle income countries with significant wider planetary implications (e.g. on food, environment and biodiversity).

Not unexpectedly, poverty in high-income countries is less affected, but not immune to financial crises. This is not only evident in income-based indicators of poverty, but unexpectedly touches also upon areas of basic needs such as access to basic water. Further research is needed to test and contextualise these results.

Along with income-based poverty, the most disruptive effect of crises is on education. Financial crises hit both government policies (reduction on education expenditure) and directly households (children out of school at primary school age). This is a critical aspect for SDGs attainment, as lack of education locks countries and individuals into a vicious circle of poverty. This is an issue of ultimate priority for the international community. Redirecting limited resources from education and public services to debt repayment will not leave poor and developing countries with better public finances, will just enhance the sources that feed and reproduce their poverty.

Our evidence on economic costs due to premature deaths from particulate matter pollution, in global region, low-income, lower-middle income and upper-middle income countries comes to confirm recent WHO (2018) facts that refers to air pollution as a major global threat to health and climate, leading to an estimated 4.2 million premature deaths per year due to strokes, heart diseases, lung cancer and chronic respiratory diseases. We also find some evidence of deforestation during financial crises, in the form of increases in net forest land CO2 emissions, but only in low-income and high-income countries.

Not all our results, however, are negative. For instance, we deem our counterintuitive findings on access to basic water equally important. Comprehensive global data on access to basic water are available only since 2000. Thus, our model essentially captures the significant progress achieved in this area since 2000. Indeed, the respective Millennium Development Goal of halving the proportion of global population without access to clean and safe drinking water by 2015, was achieved 5 years earlier in 2010 (2.6 billion people had gained access to improved drinking water since 1990). Of course the problem has not been solved, as 3 in 10 people still lack access to safely managed drinking water services (see Weststrate et al. 2019; Alcamo 2019). Respective dynamics should underlie also our counterintuitive results on infant mortality with data going back to 1980. These counterintuitive results, especially with regard to access to drinking water, demonstrate the positive impact that concerted international efforts can have despite any local adverse socioeconomic shocks as well as the degree of determination and proactive action that is needed if poverty is to be eradicated.

The adopted Multidimensional Poverty Framework exposes also an interesting contrast in poverty dynamics over recent decades. The significant gains that we have seen in very basic areas of subsistence (e.g. infant mortality, water) in the context of financial crises and beyond, are not replicated in areas that feed and sustain poverty dynamics (e.g. education, electricity). Put differently, although there is still substantial distance to be covered, there has been considerable progress towards the target of ‘surviving poverty’. Much less so is the case with the target of ‘escaping poverty’. This is a significant message from our Multidimensional Poverty analysis. Without addressing the forces that sustain poverty, the declaration of consequent ‘Development Goals’ international initiatives will end up being a permanent feature of our international society—always bringing us nominally closer to the target, but never able to meet it.

One of the most important factors governing more successful and potentially cost-effective implementation of the SDGs lie in identifying potential positive and negative synergies between individual targets (SSRP 2018). This has taken off with investigations into the effects of implementing individual targets (e.g. Nerini et al. 2018; Diz et al. 2017) or attempting to link all SDGs (International Council for Science 2017). In line with our analysis, Pardhan et al. (2017) have also identified that SDG1 on poverty has synergistic relationships with most other SDGs, with stronger statistical links to SDGs 3 (Good health and wellbeing), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 6 (Clean water and sanitation) and 10 (Reduced inequalities). In our analysis, we have presented an adjusted Multidimensional Poverty Framework incorporating income, basic needs, health, education and environment, allowing us to investigate positive or negative synergies of multiple parameters related to poverty, not just those stated in SDG1. Our results point to a number of dynamic linkages between different aspects of poverty. An increase in poverty headcount and poverty gap during a financial crisis, corresponds to a decrease in access to basic sanitation (SDG1), a decrease in access to electricity (SDG7), an increase in maternal mortality (SDG3), an increase in particulate pollution (SDG11, 13), a higher number of children out of school and a decrease in the education expenditure (SDG4), an increase in CO2 from forest removals and forest rents (SDG15 and SDG12), and a decrease in terrestrial land protection (SDG15). Not all links are clear cut or have a unidirectional impact. A decrease in agricultural land may have an influence on food security (SDG3) as well as natural land regeneration (SDG15). An increase in forest rents may have a positive immediate effect on income from natural resources (SDG1, 12) but may negatively affect SDG15 and long-term environmental poverty, if the wood harvests are unsustainably sourced. Using this Multidimensional Poverty Framework approach helps up understand dynamic linkages between different aspects of poverty, but also warns of a domino effect on a number of SDGs if the current problem of slow burning financial crises in low-income countries is not decisively and preemptively addressed.

In this sense, the keys for the success or failure of the Agenda 2030 and the target of ‘leaving no one behind’ may be in the SDG 17, Partnerships for the Goals. As we have mentioned in the beginning of the paper, for many low-income countries debt distress and financial crisis are not dangers to be avoided in the future but a reality, and debt repayment costs have gone up for most developing countries, in some cases at devastating levels. Target 17.4 refers explicitly to the need and outlines the framework for global action in this regard: ‘Assist developing countries in attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies aimed at fostering debt financing, debt relief and debt restructuring, as appropriate, and address the external debt of highly indebted poor countries to reduce debt distress’. This is a long-standing pending issue in global economic history and one can legitimately be pessimistic that the needed institutions and arrangements will be implemented in time. But in a period when deglobalisation dynamics seem to dominate and the remaining social fabric of the international community is torn apart by excessive inequalities, it seems to be an issue that can bring citizens and governments together creating new purpose and dynamic for the Agenda 2030. In this context, the IMF, with its expertise in financial crises, has an important role to play, by effectively integrating the SDG targets in its debt sustainability framework for low-income countries, and proactively and preemptively leading and coordinating the global policy that is urgently needed in the framework of SDG Target 17.4.

Conclusion

This paper has analysed the role of financial crises on the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, especially in relation to poverty indicators. We have used an adjusted Multidimensional Poverty approach addressing poverty’s multiple social, economic and environmental facets in an integrated way. This has been achieved using an econometric approach of general-to-specific (GETS) modelling on 150 countries over the period 1980–2015 and separating countries into four income groups: low income, lower-mid income, upper-mid income and high income.

We offer new estimates on the potential impact of financial distress on the SDG target of eradicating poverty. This is an issue of imminent importance, as according to the IMF (2018a) eight low-income countries are now in debt distress and sixteen more are facing a high risk of debt distress. Furthermore, debt repayment obligations have risen significantly across developing countries and global debt dynamics indicate that a new global financial crisis may be in the making (IMF 2018b). In this context, our results indicate that key poverty dynamics in low-income countries will get worse rather than better in the near future (including, poverty headcount and poverty gap, access to electricity, maternal mortality, particulate material health damage, children out of school and government expenditure on education, forest rents and reduction in biodiversity). The implementation of SDGs, especially in low-income countries, should be ‘remodelled’ to take into account existing financial distress and crisis impact estimates. In this context, the SDG target 17.4 on attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies requires urgent attention and should be ‘activated’ sooner rather than later, to give the implementation of the SDGs a chance.

The use of the Multidimensional Poverty Framework makes it clear that the problem of poverty and its eradication cannot be effectively dealt within the ‘boundaries’ of SDG1. Attempting to eradicate poverty by focusing only on SDG1 will distort our understanding of progress made and may come at the cost of other poverty dimensions (e.g. environment). Our analysis highlights the interconnectedness of different SDGs related to poverty. Although synergies are supposedly built into different SDGs, there is a constant risk that focusing on individual SDGs separately will hamper our capacity to meet the target of eradicating poverty.

The use of the Multidimensional Poverty Framework allows a better grasp of different poverty components and their interconnections. Financial crises have a significant negative impact on people’s livelihoods (especially in low-income countries), and a significant positive impact on the forces and mechanisms that sustain poverty. To meet the target of eradicating poverty we need an integrated, holistic approach to the phenomenon of poverty. The MPF offers a solid starting point for this. Including environmental aspects is key here both for short and long-term poverty dynamics (e.g. health damage, depletion of natural resources, biodiversity loss). There can be no sustainable escape from poverty that does not account for environmental sustainability.

References

Achard F, Eva HD, Mayaux P, Stibig H‐J, Belward A (2004) Improved estimates of net carbon emissions from land cover change in the tropics for the 1990s. Global Biogeochem Cycles 18(GB2008):1–12

Afonso A, Grüner HP, Kolerus C (2010) Fiscal policy and growth: do financial crises make a difference? ECB Working Paper No 1217, ECB, Frankfurt

Afzal M, Ansari MF, Shibli M, Ahmed N (2014) Factors affecting suspended particulate matter concentration in multi-storied buildings. Int J Environ Res Dev 4(3):227–232

Alcamo J (2019) Water quality and its interlinkages with the sustainable development goals. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 36:126–140

Alexander KT, Dreibelbis R, Freeman MC, Ojeny B, Rheingans R (2013) Improving service delivery of water, sanitation, and hygiene in primary schools: a cluster-randomized trial in western Kenya. J Water Health 11(3):507–519

Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A, Gemmill A et al (2016) Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. Lancet 387:462–474

Alkira S, Sumner A (2013) Multidimensional poverty index and the post-2015 MDGs. OPHI, Oxford

Alkire S, Santos ME (2010) Multidimensional poverty index. OPHI, Oxford

Alkire S, Roche JM, Santos ME, Seth S (2011) Multidimensional poverty index 2011: brief methodological note. OPHI Briefing 5. University of Oxford

Allahyari MS, Koundinya V (2013) Effective factors on agricultural land use change in Guilan effective factors on agricultural land use change in Guilan Province, Iran. Mediter J Soc Sci 4(11):744–751

Al-mulali U (2012) Factors affecting CO2 emission in the Middle East: a panel data analysis. Energy 44(1):564–569

Anderson I, Axelson H, Tan B (2011) The other crisis: the economics and financing of maternal, newborn and child health in Asia. Health Policy Plan 36:288–297

Angelsen A, Resosudarmo DP (1999) Krismon, farmers and forests: the effects of the economic crisis on farmers’ livelihoods and forest use in the outer islands of Indonesia. (Unpublished Manuscript): CIFOR, Bogor http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=GB2013202417. Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Angelsen A, Wunder S (2003) Exploring the forest—poverty link: key concepts, issues and research implications, CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 40, Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor

Antoniades A, Griffith-Jones S (2018) Global debt dynamics: the elephant in the room. World Econ 41(12):3256–3268

Barkema HG, Bell JHJ, Pennings JM (1996) Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strateg Manag J 17:151–166

BIS (2018) Quarterly Review: International banking and financial market developments. BIS, Basel

Borenstein S (2012) The private and public economics of renewable electricity generation. J Econ Perspect 26(1):67–92

Brenner MH (1973) Fetal, infant, and maternal mortality during periods of economic instability. Int J Health Serv 3(2):145–159

Burke K, Beegle K (2004) Why children aren’t attending school: the case of Northwestern Tanzania. J Afr Econ 13(2):333–355

Busemeyer MR (2007) Determinants of public education spending in 21 OECD democracies, 1980–2001. J Eur Public Policy 14(4):582–610

Buys G, Thomson A, Moxley J, Malcolm H, Henshall P (2017) Mapping carbon emissions & removals for the land use, land use change & forestry sector. Report prepared by the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology for the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, Penicuik

Cecchetti S, Mohanty M, Zampolli F (2011) The real effects of debt. Working papers No 352, BIS, Basel

Chakrabarti A, Joglekar R (2006) Determinants of expenditure on education: an empirical analysis using state level data. Econ Political Wkly 41(15):1465–1472

Chandy L, Ledlie N, Penciakova V (2013) The final countdown: prospects for ending extreme poverty by 2030. Policy Paper 2013-04. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

Chen S, Ravallion M (2010) The developing world is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty. Q J Econ 125(4):1577–1626

Chen G, Li S, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Li D, Wei X, Guo Y (2017) Articles effects of ambient PM 1 air pollution on daily emergency hospital visits in China: an epidemiological study. Lancet Planet Health 1:e221–e229

Clemens M, Kenny C, Moss T (2007) The trouble with the MDGs: confronting expectations of aid and development success. World Dev 35(5):735–751

Curtis PG, Slay CM, Harris NL, Tyukavina A, Hansen MC (2018) Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 361(6407):1108–1111

Devarajan S (2015) Shame on me: why it was wrong to cost the Millennium Development Goals. Future development. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

Diorio A, Crivelli-kovach A (2014) The global and local factors influencing maternal mortality ratios: barriers and recommendations for success. J Soc Sci Policy Implic 2(3):33–60

Diz D, Morgera E, Wilson M (2017) Marine policy special issue: SDG synergies for sustainable fisheries and poverty alleviation. Marine Policy 110:1–2

Dube B, January J (2012) Factors leading to poor water sanitation hygiene among primary school going children in Chitungwiza. J Public Health Afr 3:25–28

Eichengreen B, Park D, Shin K (2017) The landscape of economic growth: do middle-income countries differ? ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 157, Asian Development Bank, Manila

Fairhead J, Leach M, Scoones I (2012) Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature? J Peasant Stud 39(2):237–261

Filippidis FT, Gerovasili V, Millett C, Tountas Y (2017) Medium-term impact of the economic crisis on mortality, health-related behaviours and access to healthcare in Greece. Sci Rep 7(46423):1–7

Food and Agriculture Organization (2018) Global Land Cover-SHARE (GLC-SHARE). http://www.fao.org/land-water/land/land-governance/land-resources-planning-toolbox/category/details/en/c/1036355/. Accessed 20 October 2018

Freedman DA (2006) On the so-called “huber sandwich estimator” and “robust standard errors”. Am Stat 60(4):299–302

Ghouali YZ, Belmokaddem Mostefa Sahraoui MA, Guellil MS (2015) Factors affecting CO2 emissions in the BRICS Countries: a panel data analysis. Procedia Econ Financ 26:114–125

Harper C (2009) The Global Financial crisis: identifying the chronically poor in low income countries. https://www.odi.org/comment/4245-global-financial-crisis-identifying-chronically-poor-low-income-countries. Accessed 12 Jan 2019

Hendry DF, Krolzig H-M (2004) We ran one regression. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 66(5):799–810

Hoover KD, Perez SJ (1999) Data mining reconsidered: encompassing and the general-to-specific approach to specification search. Econom J 2:167–191

Hoover KD, Perez SJ (2004) Truth and robustness in cross-country growth regressions. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 66(5):765–798

Huber PJ (1967) The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In: Proceedings of the fifth berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, vol 1. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 221–233

Hulme D, Shepherd A (2003) Conceptualizing chronic poverty. World Dev 31(3):403–423

Imai N, Furukawa T, Tsujino R, Kitamura S (2018) Factors affecting forest area change in Southeast Asia during 1980–2010. PLoS One 13(5):e0197391

Imana DK (2017) The determinants of public education expenditures : an empirical analysis of changing patterns and growth of public expenditure on education in Kenya. J Public Adm Gov 7(4):1–23

IMF (2018a) Macroeconomic developments and prospects in low-income developing countries—2018. IMF, Washington DC

IMF (2018b) Global financial stability report—a decade after the global financial crisis: are we safer?. IMF, Washington, DC

IMF (2019) World economic outlook update: a weakening global expansion. IMF, Washington DC

Development Initiatives (2013) Investments to end poverty: real money, real choices, real lives. Development Initiatives, Bristol

Development Initiatives (2018) Investments to end poverty: meeting the financing challenge to leave no one behind. Development Initiatives, Bristol

International Council for Science (2017) A guide to SDG interactions: from science to implementation. International Council for Science, Paris

Jubilee Debt Campaign (2018) Developing country debt payments increase by 60% in three years. Jubilee Debt Campaign, London, March 2018

Kaasa A (2003) Factors influencing income inequality in transition economies. University of Tartu Economics and Business Administration Working Paper Series 18, University of Tartu Economics and Business Administration, Tartu

Kemmler A (2007) Factors influencing household access to electricity in India. Energy Sustain Dev 11(4):13–20

Kulild V (2014) Role of education in ending extreme poverty—taking a global lead. In: The carita seminar on the United Nations sustainable development goals and post-2015 development agenda, Oslo. https://norad.no/en/front/about-norad/news/role-of-education-in-ending-extreme-poverty–taking-a-global-lead/. Accessed 11 Nov 2014

Laeven L, Valencia F (2018) Systemic banking crises revisited. IMF Working Paper No. WP/18/206, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC

Leahy J, Schipani A (2018) Brazil: rainforest pays the price for the country’s crisis. https://www.ft.com/content/971f03aa-f9e0-11e7-9b32-d7d59aace167. Accessed 12 Jan 2018

Lee K, Lu S, Shih Y (2018) Contagion effect of natural disaster and financial crisis events on international stock markets. J Risk Financ Manag 11(2):16

Lekakis JN, Kousis M (2013) Economic crisis, troika and the environment in Greece. South Eur Soc Politics 18(3):305–331

Liu ZG, Wang SS, Liu JY, Liu F, Fu XL (2013) Analysis of factors affecting CO2 emissions by civil buildings in China’s urban areas. Int J Low Carbon Technol 10:460–463

Loria K (2018) CO2 levels are at their highest in 800,000 years. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/05/earth-just-hit-a-terrifying-milestone-for-the-first-time-in-more-than-800-000-years. Accessed 20 Jan 2018

Makino S, Isobe T, Chan CM (2004) Does country matter? Strateg Manag J 25:1027–1043

Manuel Marcus, Desai Harsh, Samman Emma, Evans Martin (2018) Financing the end of extreme poverty. ODI, London

McGahan AM, Mitchell W (2003) How do firms change in the face of constraints to change? Toward an agenda for research on strategic organization. Strateg Org 1(2):231–239

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, M.E.A (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being. Island Press, Washington, DC

Mills Busa JH (2013) Deforestation beyond borders: Addressing the disparity between production and consumption of global resources. Conserv Lett 6(3):192–199

Nerini FF, Tomei J, To LS, Bisaga I, Parikh P, Black M, Borrion A, Spataru C, Broto VC, Anandarajah G, Milligan B (2018) Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the sustainable development goals. Nat Energy 3(1):10

OECD (2013) What is the impact of the economic crisis on public education spending? Education indicators in focus, no 18. OECD Publishing, Paris

Okumu I, Nakajjo A, Isoke D (2008) Socioeconomic determinants of primary school dropout: the logistic model analysis. EPRC Research Series No. 54. Makerere University, Kampala

OPHI (2016) How to incorporate environmental and natural resources (ENR) considerations into multidimensional poverty. Inception Report, OPHI, Oxford

Pacca L, Antonarakis A, Schröder P, Antoniades A (2020) The effect of financial crises on air quality: an assessment of the short vs medium-run effect. Sci Total Environ 698:133612

Pagiola S (2001) Deforestation and land use changes induced by the East Asian economic crisis. EASES Discussion Paper Series. World Bank, Washington, DC

Papi L, Presbitero A, Zazzaro A (2015) IMF lending and banking crises. IMF Working Paper No 15/19, IMF, Washington DC

Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Schroeder DG, Habicht J-P (1995) The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 73(4):443–448

Piesse J, Thirtle C (2009) Three bubbles and a panic: an explanatory review of recent food commodity price events. Food Policy 34(2):119–129

Poloamina ID, Umoh UC (2013) The determinants of electricity access in Sub-Saharan Africa. Empir Econom Quant Econ Lett 2(4):65–74

Pradhan P, Costa L, Rybski D, Lucht W, Kropp JP (2017) A systematic study of sustainable development goal (SDG) interactions. Earth’s Future 5(11):1169–1179

Pretty J, Benton TG, Bharucha ZP, Dicks LV, Flora CB, Godfray HCJ, Goulson D, Hartley S, Lampkin N, Morris C, Pierzynski G (2018) Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nat Sustain 1(8):441

Rajmil L, de Sanmamed MF, Choonara I, Faresjö T, Hjern A, Kozyrskyj A, Taylor-Robinson D (2014) Impact of the 2008 economic and financial crisis on child health : a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11:6528–6546

Ravallion M, Chen S (2009) The impact of the global financial crisis on the world’s poorest. https://voxeu.org/print/3520. Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Rice AL, Sacco L, Hyder A, Black RE (2000) Malnutrition as an underlying cause of childhood deaths associated with infectious diseases in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 78(10):1207–1221

Rutstein SO (2000) Factors associated with trends in infant and child mortality in developing countries during the 1990s. Bull World Health Organ 78(10):1256–1270

Sachs J, Schmidt-Traub G, Kroll C, Lafortune G, Fuller G (2019) Sustainable development report 2019. Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), New York

Scharlemann JPW et al (2016) Global goals mapping: the environment-human landscape. SSRP and UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge

Schmidt-Traub G (2015) Investment needs to achieve the sustainable development goals: understanding the billions and trillions. Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Working Paper, New York

Schreckenberg K, Mace G, Poudyal M (2018) Ecosystem services for poverty alleviation: trade-offs and governance. Routledge, London

Schulze K, Knights K, Coad L, Geldmann J, Leverington F, Eassom A, Marr M, Butchart S, Hockings M, Burgess N (2018) An assessment of threats to terrestrial protected areas. Conserv Lett 11:e12435. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12435.5

Sen A (1976) Poverty: an ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica 44(2):219–231

Shafiq MN (2010) The effect of an economic crisis on educational outcomes: an economic framework and review of the evidence. Curr Issues Comp Educ 12(2):5–13

Siddiqui A, Iram U (2007) Socioeconomic determinants of school progression in Pakistan. Appl Econom Int Dev 7(2):179–196

Slocumb JC, Kunitz SJ (1977) Factors affecting maternal mortality and morbidity among American Indians. Public Health Rep 92(4):349–356

SSRP (2018) Achieving the SDGs: building on interlinkages among goals. Wilton Park Report, WP1608, March

Streeten P (1979) From growth to basic needs. Finance Dev 16:28–31

The World Bank (2018a) World Bank Country and Lending Groups—World Bank Data Help Desk. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 10 Oct 2018

The World Bank (2018b) World Development Indicators (WDI) | Data Catalog. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators. Accessed 15 Oct 2018

Thiry G, Alkire S, Judith Schleicher J (2018) Incorporating environmental and natural resources within analyses of multidimensional poverty. Research in Progress Series 50a. OPHI, Oxford

Uitto JI (2016) The environment-poverty nexus in evaluation: implications for the sustainable development goals. Global Policy 7(3):441–447

UN (2013) A New Global partnership: eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development. The Report of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, UN, New York

UN (2018). Financing for development: progress and prospects 2018. Report of the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development, UN, New York

UNCTAD (2018) Financing for development: debt and debt sustainability and interrelated systemic issues. Submitted to Trade and Development Board-Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Financing for Development, Geneva, 7–9 Nov

UNDP (2019) The 2019 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-MPI. Retrieved 18 Dec 2019

Wendling ZA, Emerson JW, Esty DC, Levy MA, de Sherbinin A, et al. (2016) 2016 Environmental performance index. Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, New Haven. https://epi.yale.edu/. Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Wendling ZA, Emerson JW, Esty DC, Levy MA, de Sherbinin A, et al. (2018) 2018 Environmental performance index. Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, New Haven. https://epi.yale.edu/. Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Weststrate J, Dijkstra G, Eshuis J et al (2019) The sustainable development goal on water and sanitation. Soc Indic Res 143:795–810

White H (1980) A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48:817–830

WHO (2018) Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health. Accessed 25 Feb 2019

WHO (2019) Maternal mortality. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. Retrieved 18 Dec 2019

Widiarto I, Emrouznejad A, Anastasakis L (2017) Observing choice of loan methods in not-for-profit microfinance using data envelopment analysis. Expert Syst Appl 82:278–290

World Bank (2019) Global economic prospects: darkening skies. World Bank Group, Washington DC

Wrisdale L, Mokoena MM, Mudau LS, Geere J (2017) Factors that impact on access to water and sanitation for older adults and people with disability in rural South Africa : an occupational justice perspective. J Occup Sci 24(3):259–279

Zhang Y, Jiang W (2018) Pollution characteristics and influencing factors of atmospheric particulate matter (PM2. 5) in Chang-Zhu-Tan area. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 108:1–6

Zhou Y, Levy JI (2007) Factors influencing the spatial extent of mobile source air pollution impacts: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 7(89):1–11

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Patrick Schröder, Joseph Alcamo, Caroline Grundy, Beate Jahn, Peter Newell, Lucia Pacca, two anonymous reviewers and our colleagues at the Sussex Sustainability Research Programme for comments in earlier versions of this paper. Any errors remain our responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research was funded by the Sussex Sustainability Research Programme (SSRP) (Grant number SSRP2016-004), University of Sussex, UK.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handled by Joseph Alcamo, University of Sussex, United Kingdom.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antoniades, A., Widiarto, I. & Antonarakis, A.S. Financial crises and the attainment of the SDGs: an adjusted multidimensional poverty approach. Sustain Sci 15, 1683–1698 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00771-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00771-z