Abstract

Background

Antipsychotics (APs) increase weight, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Guidelines recommend cardio-metabolic monitoring at initial assessment, at 3 months and then annually in people prescribed APs.

Aim

To determine the rates of cardio-metabolic monitoring in AP treated early and chronic psychosis and to assess the impact of targeted improvement strategies.

Methods

Medical records were reviewed in two cohorts of first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients before and after the implementation of a physical health parameter checklist and electronic laboratory order set. In a separate group of patients with chronic psychotic disorders, adherence to annual monitoring was assessed before and 3 months after an awareness-raising educational intervention.

Results

In FEP, fasting glucose (39% vs 67%, p=0.05), HbA1c (0% vs 24%, p=0.005) and prolactin (18% vs 67%, p=0.001) monitoring improved. There were no significant differences in weight (67% vs 67%, p=1.0), BMI (3% vs 10%, p=0.54), waist circumference (3% vs 0%, p=1.0), fasting lipids (61% vs 76% p=0.22) or ECG monitoring (67% vs 67%, p=1.0). Blood pressure (BP) (88% vs 57%, p=0.04) and heart rate (91% vs 65%, p=0.03) monitoring dis-improved. Diet (0%) and exercise (<15%) assessment was poor. In chronic psychotic disorders, BP monitoring improved (20% vs 41.4%, p=0.05), whereas weight (17.0% vs 34.1%, p=0.12), BMI (9.7% vs 12.1%, p=1.0), fasting glucose (17% vs 24.3%, p=0.58) and fasting lipids remained unchanged (17% vs 24.3%, p=0.58).

Conclusions

Targeted improvement strategies resulted in a significant improvement in a limited number of parameters in early and chronic psychotic disorders. Overall, monitoring remained suboptimal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Improving physical health outcomes in people with psychotic disorders remains a major concern and challenge [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The 15–20-year mortality gap between people with chronic psychotic disorders and the general population may even be widening [7,8,9,10,11,12]. The majority of the excess deaths are due to partially modifiable physical diseases, such as premature cardiovascular disease (CVD), respiratory disease and infection [13,14,15,16]. In the current pandemic, people with schizophrenia are seven times more likely to contract COVID-19 than the general population and have twice the mortality rate (8.5% vs. 4.7%) [17]. Given the increased risk of COVID-19 associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome [18,19,20,21], which are elevated in both early [22] and chronic [23] psychotic disorders, the disparities are likely to increase further.

A complex interaction between lifestyle factors [24], AP side effects and lower-quality healthcare [25, 26] contributes to the higher cardio-metabolic risk. People with chronic psychotic disorders are at a two to three times higher risk of dying from CVD than the general population [27, 28]. Up to 75% of patients with schizophrenia, compared with approximately 33% in the general population, die of coronary heart disease [16], and approximately 66% will have multiple physical conditions [29, 30]. People with chronic psychotic disorders have increased levels of obesity (50%), metabolic syndrome (30%) [23, 31], glucose intolerance (25%) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (10%) [32], together with high levels of smoking [33], poor diet [34, 35] and low physical activity levels [36].

Not only are some cardio-metabolic risk factors evident at the earliest stages of psychosis [22, 37, 38], even with minimal AP exposure [23, 39,40,41,42], persistently high fasting insulin levels during childhood are associated with an increased risk of developing a psychosis at-risk mental state and psychotic disorder [43]. APs, by a combination of central and peripheral actions, for example 5-HT2C and histamine receptor antagonism, together with an inhibition of insulin signalling pathways, greatly increase the risk of metabolic dysregulation, diabetes and CVD [7, 15, 44, 45]. Metabolic risk profiles vary between APs [46,47,48], with olanzapine and clozapine being the worst [49,50,51], whereas aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone and ziprasidone have the most benign metabolic profiles [52, 53]. Weight gain can occur within weeks of starting APs [54]. In the CATIE study, 30% of people with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine gained 7% or more of their baseline body weight [55], whereas the EUFEST (European First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial) showed that up to 50% of individuals who were treatment-naive gained over 7% of body weight within 1 year [56].

Guidelines state that cardio-metabolic monitoring should be carried out at initial assessment, at 3 months and then annually in people prescribed APs [57, 58]. The Second National Audit of Schizophrenia (NAS) in 2014 of 5500 people in community mental health services showed minimal improvement in the monitoring of physical health parameters compared with 2012 [59,60,61]. Only 33% of people with schizophrenia had all five key physical health risk factors (smoking, weight, blood glucose, blood lipids, blood pressure) monitored, compared with 29% in 2012 [59]. Monitoring of glucose control increased from 50 to 57%, but when abnormal levels were identified, further support was offered in 36% of cases, which dis-improved compared with 2012 (53%). Lipid monitoring increased from 47 to 57%, and approximately half had their BMI checked in 2014 (52%) and 2012 (51%) [59]. A recent cross-sectional study of routine cardio-metabolic monitoring in patients treated with long-acting injectable (LAI) APs (n=116) showed that less than 45% of medical records had documentary evidence of metabolic monitoring over the previous 6 months [31].

The persistent physical health monitoring and implementation deficits highlighted in the second NAS prompted a movement towards greater integration between primary and secondary care and shared responsibility of physical health monitoring/treatment in psychiatric patients. Additionally, it launched the National Health Services (NHS) Lester Positive Cardio-metabolic Health Resource Tool encompassing the “don’t just screen, intervene” strategy [62, 63]. More recently, the Maudsley prescribing guideline series has launched practice guidelines for Physical Health Conditions in Psychiatry [64].

The most recent data from the Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) spotlight audit (2019) in the UK, including 9631 patients, demonstrated a marginal improvement compared with the NAS [59,60,61]. In this EIP audit, 64% had been screened for all seven physical health measures (smoking, alcohol use, substance misuse, BMI, blood pressure, blood glucose, lipids) [65]. The rates of intervention varied between measures, from 66% for elevated blood pressure to 93% for harmful/hazardous use of alcohol [65].

In general, rates of monitoring tend to be worse for male patients, younger patients (16–44 years) and those with schizophrenia [66]. Several previous studies have demonstrated that various interventions can improve the rates of cardio-metabolic health monitoring in early [67] and chronic psychotic disorders [68,69,70,71,72], including efforts to monitor physical health in people’s homes [73]. The HSE National Model of Care for EIP Services (2018) in line with UK guidelines [57, 58] stipulates that weight, BMI, pulse, blood pressure, physical examination, ECG and routine bloods (including fasting glucose/lipids, HbA1c and prolactin levels) should be completed as part of the initial assessment, at 3 months and then annually or more frequently if indicated [74]. In parallel, a comprehensive assessment of lifestyle factors and corresponding lifestyle advice should be conducted [74].

While there is an abundance of research investigating cardio-metabolic monitoring improvement strategies in people with psychotic disorders [67,68,69,70,71,72,73, 75], to the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated metabolic monitoring including lifestyle assessment in FEP in the Irish context. Given the considerable rates of cardio-metabolic pathology, exacerbated by APs, and the persistent deficiencies in the monitoring of modifiable risk factors across the psychosis disorder spectrum, we aimed to determine the baseline rate of monitoring in AP treated FEP patients and separately, in patients with chronic psychosis treated with LAI APs. We then investigated whether pragmatic interventions could improve monitoring rates in both groups.

Methods

Audit standards

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. CG178 [58] and NICE quality standards in relation to treating and managing psychosis (QS80, Quality statement 6; QS102, Quality statement 6) were used.

The guidelines recommend that 100% of FEP individuals should have the following physical health parameters recorded in clinical files during commencement of AP medication.

-

Baseline monitoring

-

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG), fasting blood glucose, fasting lipids, prolactin.

-

-

Physical examination

-

-

Weight, height, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), abnormal movement assessment.

-

-

Lifestyle assessment

-

-

Documented enquiry about (i) smoking history, (ii) alcohol use, (iii) illicit drug misuse, (iv) prescription drug misuse, (v) personal family/medical history and (vi) physical activity levels.

-

-

Lifestyle advice

-

-

Documentation of advice given on (i) illicit drug misuse, (ii) prescription drug misuse, (iii) alcohol misuse, (iv) recommended physical exercise.

-

Modification of guidelines

The severity of psychotic illness has implications for behaviour and can affect a patient’s willingness to engage in monitoring and examination. Therefore, after a consensus meeting, it was decided that all physical health parameters recorded within 2 weeks of commencing an AP were acceptable.

Annual monitoring for those on long-term APs

-

Weight, BMI, blood pressure (BP), fasting glucose, fasting lipids.

Inclusion criteria/eligibility criteria

FEP

All patients aged (16–65 years) enrolled in the Dublin South City First Episode Psychosis Programme (DSFEP), St. James’s Hospital, prescribed AP medication were included. The initial audit included all individuals enrolled on the Programme over an 18-month period from January 2015 to June 2016. The re-audit included individuals enrolled over a 12-month period from December 2016 to December 2017.

Chronic psychosis

All adult (18–75 years) patients with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective, delusional disorder) receiving long-acting injectable (LAI) APs attending the CAMAC Community Mental Health Service at St. James’s Hospital in October 2016 were included. Patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder and depression were excluded.

Intervention

FEP

Clinical records, medication records and hospital electronic records were reviewed by (PG, TOC, ZL, RMcC, RF, AMcL, LM, MH) using a study-specific data collection tool.

Chronic psychosis

Clinical records were reviewed before and 3 months after (January 2017) the implementation of an awareness raising-educational intervention aimed at improving rates of cardio-metabolic monitoring.

Physical health parameter checklist (FEP)

On completion of the initial audit, recommendations to improve adherence to physical health monitoring guidelines were implemented, including the following: development of an evidence-based physical health parameter checklist in hard copy format for completion by medical staff was incorporated into the general admission template at a service wide level.

Pre-antipsychotic electronic laboratory order set (FEP)

A service-wide pre-AP prescribing blood order set was established. Order sets are a form of clinical decision support system (CDSS) where a limited set of evidence-based tests are proposed for a series of indications, integrated in a computerized clinician order entry. The specific pre-AP profile was incorporated into the hospital electronic system with assistance of the IT department, making it accessible to all clinicians in the service. Clinicians were prompted to enter baseline laboratory tests for those patients with psychosis through a searchable drop-down menu of common indications selected through tick boxes. Selecting one or more of these indications prompted a new window with the appropriate tests for the indications. This facilitated efficient FEP blood ordering on the patient’s initial contact with the service via their electronic record.

Awareness-raising educational sessions (FEP and chronic psychosis group)

Educational sessions with members of the MDT were conducted at interdepartmental meetings. These educational meetings focused on the rationale for routine screening and monitoring of physical health parameters, and provided an opportunity to discuss potential service-specific barriers to monitoring (i.e. resources/equipment/clinician time and availability). As such, these sessions provided a forum to problem-solve around these barriers and explore potential solutions. Feedbacks of baseline audit results were presented at MDT meetings, case conferences and audit meetings in the Department of Psychiatry St. James’s Hospital.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact in GraphPad was used to determine differences in the proportion of patient records in compliance with standards pre and post-intervention.

Results

Demographics

See Table 1.

Antipsychotics

Prescribed APs in FEP are shown in Table 2. In the chronic psychosis group, 75.6% (31/41) were prescribed only second-generation antipsychotics (SGA), 14.6% (6/41) were prescribed only first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) and 9.8% (4/41) were prescribed both SGA and FGA.

First-episode psychosis

In the first cohort, 35 patients enrolled in the DSFEP programme over the 18-month period of initial audit. Two patients were excluded as they were not prescribed APs. In the second cohort, 21 patients enrolled in the DSFEP programme over a 12-month period. One patient was excluded as was not prescribed APs.

Changes in cardio-metabolic parameters in FEP post-intervention

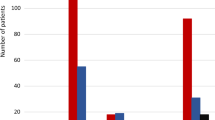

Monitoring of fasting glucose (p=0.047), HbA1c (p=0.005) and prolactin (p=0.001) significantly improved at re-audit (Fig. 1). Conversely, the monitoring of blood pressure (p=0.039) and heart rate (p=0.03) significantly dis-improved. There were no significant changes in fasting lipids (p=0.23), weight (p=1.0), BMI (p=0.54), waist circumference (p=1.0) or ECG monitoring (p=1.0) (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Monitoring of physical health parameters. a There were significant improvements in the monitoring of fasting glucose (p=0.047), HbA1c (p=0.005) and prolactin levels (p=0.001) after the implementation of targeted improvement strategies in FEP. There were no changes in the rate of ECG, weight or BMI monitoring. Blood pressure (p=0.039) and heart rate (p=0.03) monitoring dis-improved (data not shown). b The routine monitoring of blood pressure improved (p=0.053) post-intervention in the chronic psychotic disorders group (HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin, FEP: first-episode psychosis, ECG: electrocardiogram, BMI: body mass index)

Changes in lifestyle assessment parameters in FEP post-intervention

There was a significant improvement in the recording of prescription drug misuse (p=0.01) from baseline to re-audit. In contrast, the documentation of illicit drug misuse (p=0.01) and alcohol misuse (p=0.047) advice decreased from baseline to re-audit. There were no other significant lifestyle assessment or advice parameter changes.

Changes in cardio-metabolic parameters in chronic psychosis post-intervention

The routine monitoring of blood pressure improved (p=0.053) post-intervention (Fig. 1b). There were no significant changes in the monitoring of weight, BMI, waist circumference, fasting glucose or fasting lipids post-intervention (Table 2).

Four percent of the sample had diabetes (DM), though none were prescribed diabetic treatment. Hypertension (HTN) was recorded in 9.7%, of which 2.4% were prescribed anti-hypertensive treatment (Table 3). GPs were notified of DM or HTN findings via a letter.

Cardio-metabolic parameters in FEP compared with chronic psychosis post-intervention

The rates of weight (p=0.03), fasting glucose (p<0.001) and fasting lipids (p<0.001) monitoring were higher in the post-intervention FEP group compared with the chronic psychosis group. There were no differences in BMI, waist circumference or blood pressure (Table 3).

Discussion

This study investigated the rates of compliance with cardio-metabolic monitoring as per NICE physical health guidelines in antipsychotic (AP) treated patients with early and chronic psychotic disorders [58]. Furthermore, we determined whether the implementation of targeted improvement strategies could advance the baseline monitoring rates. We found that baseline cardio-metabolic monitoring was suboptimal in both first-episode psychosis (FEP) and chronic psychosis. In the FEP cohort, the introduction of a physical health parameter checklist and pre-AP prescribing electronic laboratory order set significantly improved the rate of blood glucose, HbA1c and prolactin monitoring (Fig. 1a). Separately, in the group with chronic psychotic disorders treated with LAIs, our psychoeducational and awareness-raising intervention significantly improved blood pressure monitoring (Fig. 1b).

While there were improvements in the monitoring of some cardio-metabolic parameters, particularly related to blood markers in FEP, overall the rates in both FEP and chronic psychosis were considerably less than the 100% stipulated by the NICE guidelines [58]. Our post-intervention rates in the FEP group, while below the 100% guidelines, were approximately in line with the most recent data from the EIP spotlight audit (2018–2019) in the UK [65], highlighting the challenges of adhering to cardio-metabolic monitoring guidelines across different health care systems.

In contrast to our high rates of smoking, alcohol and illicit drug assessment in the FEP group, the rates of diet and exercise assessment were very poor (Table 2). Notably, physical exercise, a key component in reducing cardio-metabolic risk factors in general, was discussed only in 6% at baseline and 15% at re-audit, whereas diet was not assessed. This may indicate a lack of knowledge of evidence based guidelines among health professionals caring for those with FEP or, potentially suggest a professional mindset that those with psychosis were unlikely to engage in positive lifestyle behaviours. Regardless, it represents a missed opportunity for lifestyle modification, all the more important in the early stages of psychotic disorders [38]. Ongoing education of healthcare professionals and patients is necessary to improve incorporation of lifestyle assessment and advice in daily clinical practice in mental health settings. The inclusion of a self-screening checklist, in addition to the standardized AP information leaflet distributed to all patients starting on APs, may also improve rates.

A variety of “lifestyle interventions” aimed at adjusting dietary and/or physical activity behaviours, to benefit the physical health of people with psychotic disorders have been developed in recent years [76]. The majority are based on behaviour change psychological theory and require enquiry by healthcare professionals into an individual’s current lifestyle to establish a behaviour baseline to guide individualized advice and interventions. A pilot study of a physiotherapy-led motivational programme to increase physical activity and improve cardio-metabolic parameters in people with major mental illness in St. James’s Hospital showed promising results [4], but the consistent integration of standardized, effective and implementable physical health improvement interventions for people with psychotic disorders remain a challenge [2, 77]. Positive effects can be delivered, especially if delivered early, but may only last for the duration of the intervention [78]. Motivational issues are problematic, as highlighted by a 30% non-attendance rate in a naturalistic cohort study of an exercise physiology service in an FEP programme [2] and a 34% non-attendance rate for metabolic screening in patients prescribed LAI APs [31]. We await with interest the results of a trial investigating whether the introduction of more complex interventions such as a dedicated physical health nurse into an FEP programme will improve physical health outcomes [79].

The multi-level approach to mitigating the cardio-metabolic risk in psychotic disorders also includes personalized AP treatment strategies. APs form a vital adjunct to multidisciplinary psychosocial interventions, including cognitive behavioural therapy and family interventions in early onset psychosis [80, 81]. Consequently, an AP minimization strategy [82] based on individual preferences, avoidance of polypharmacy and high doses is essential [83,84,85]. Interestingly, the Australian early psychosis guidelines switched olanzapine to second-line treatment in 2014 [86]. This reduced the rate of olanzapine as a first line agent from 25 to 20% at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) [86]. A recently published retrospective cohort study of EIP services in South County Dublin showed that 80% of EIP patients were initially prescribed olanzapine [87]. The HSE EIP model of care suggests olanzapine as a second-line agent, but advise that this “should be balanced by the relatively lower risk of extra-pyramidal side effects” [74]. In accordance, our rate of olanzapine prescribing decreased by 10% from baseline to 45% at re-audit, conversely aripiprazole doubled to 15% (Table 2).

The rates of monitoring in the FEP group were better than the chronic psychotic disorders group. Specifically, rates of weight, fasting lipids and fasting glucose monitoring were significantly higher in the post-intervention FEP group compared with the post-intervention chronic psychosis group (Table 3). While both groups incorporated awareness-raising educational sessions, only the FEP group had a specific electronic laboratory order set and physical health parameter checklist, which could account for the better rates. However, we acknowledge that a 3-month period between baseline and re-audit in the chronic psychosis group may have been insufficient. Nonetheless, our post-intervention monitoring rates in chronic psychosis, similar to the Lydon et al. study [31] were all below 45%.

Lydon et al. also highlighted the discrepancy between the higher rates of metabolic monitoring in those prescribed clozapine (>90%) compared with those in the LAI group [31]. This shows that a systematized approach such as dedicated clozapine monitoring clinics can increase metabolic monitoring. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that a dedicated metabolic clinic can improve monitoring rates in non-clozapine AP-treated patients [71]. It is noteworthy that despite the significantly higher levels of monitoring in the clozapine group, the rate of metabolic syndrome was 8% higher (at 39%) than the LAI group [31], which is most likely due to the less favourable metabolic profile of clozapine.

Prior research suggests that the prevalence of T2DM among individuals with schizophrenia is approximately 10% [32, 88]. The threshold for diagnosis of diabetes according to clinical notes or glycaemic testing in our group of people with chronic psychotic disorders was lower at 4%, which is double the rate of undiagnosed T2DM in the Irish adult population (1.8%) [89]. In terms of HTN, our 10% rate is approximately in line with the rate of clinically diagnosed HTN in the Irish population (13%) [90]. In our sample, none of the patients identified as having diabetes were on diabetic treatment (Table 3), whereas 2.4% of those identified as HTN were prescribed anti-hypertensive treatment. These findings clearly indicate a deficit in the model of shared care between primary and secondary care, which is imperative for improved outcomes for patients across the psychotic disorder spectrum [91, 92].

Undoubtedly, this could be improved by greater integration of connected IT systems between primary and secondary care [93]. At a local level, occurring post completion of this study, St. James’s Hospital introduced a hospital-wide electronic patient record (EPR) system. It would be interesting in future research to investigate whether this hospital wide EPR system has influenced the rates of cardio-metabolic monitoring and associated utilization rates of the electronic laboratory order sets. Although mental health services are often the main source of metabolic monitoring for patients, it is possible that some patients had metabolic monitoring carried out by their own GP’s. This data was not captured in our study, and this limitation of our study further re-enforces the importance of implementing a shared electronic system between primary and secondary care.

COVID-19 will likely make cardio-metabolic monitoring even more challenging, but simultaneously it may expedite the integration of enhanced IT solutions. For example, an estimated 80% of people with psychotic disorders own a mobile phone and a majority report a willingness to use this modality for self-support and enhanced contact with mental health services [94]. There are preliminary indicators that the tele-medicine approach can be useful for exercise and weight management in people with psychotic disorders [95,96,97,98,99,100], and the extension into personalized home-based physical health monitoring systems, potentially assisted by MDT members may also be on the horizon.

In summary and in keeping with previous research, our study highlights the challenges of improving cardio-metabolic health monitoring practises for people with both early- and chronic-stage psychotic disorders. This study identified suboptimal rates of cardio-metabolic monitoring and lifestyle factor assessment, notably diet and exercise in AP-treated FEP patients. Moreover, it showed that the implementation of a targeted awareness-raising educational intervention and introduction of a physical health checklist and AP electronic laboratory order set resulted in significant improvements in the monitoring of blood glucose, HbA1c and prolactin levels in FEP. Separately, a targeted awareness-raising educational intervention improved the routine monitoring of blood pressure in LAI-treated patients with chronic psychotic disorders. While awareness-raising activities may play a limited role, our study indicates that standardized systems for monitoring are more effective. In line with previous studies, our post-intervention rates of monitoring were well below the 100% guideline requirement.

Conclusions

Targeted improvement strategies resulted in significant improvements in a limited number of cardio-metabolic monitoring parameters in early and chronic psychosis. However, monitoring remained suboptimal in both groups. Improving cardio-metabolic health across the psychotic disorder spectrum requires ongoing awareness-raising and promotion of physical health among MDT members and patients, the availability of effective physical health interventions and enhanced collaboration between primary and secondary care, all facilitated by standardized systems and enhanced utilization of IT platforms. This is all the more important in the era of COVID-19.

Limitations

Direct comparisons between the FEP and the chronic psychotic disorder groups are limited as the interventions were different and occurred over different time scales. Not all post-intervention measures were captured (i.e. diet and exercise). In the group with chronic psychosis, the 3-month period between baseline and re-audit may have been insufficient to fully capture potential improvements. In chronic psychosis, the rate of cardio-metabolic monitoring could be different between those who are prescribed oral APs compared with LAI APs. The chronic psychosis group in our study only contained patients prescribed LAI APs and therefore may not be representative of the broader chronic psychosis group. In addition, the type of LAI AP was not recorded. This study focussed solely on monitoring rates and did not investigate rates of support or interventions when patients screened positively. We did not specifically seek metabolic monitoring records from GPs.

References

Vancampfort D et al (2019) The impact of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve physical health outcomes in people with schizophrenia: a meta-review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 18(1):53–66

Pearce M et al (2020) Evaluation of an exercise physiology service in a youth mental health service. Ir J Psychol Med p. 1-6

Buhagiar K, Parsonage L, Osborn DPJ (2011) Physical health behaviours and health locus of control in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder: a cross-sectional comparative study with people with non-psychotic mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 11(1):104

Waugh A et al (2018) A feasibility study of a physiotherapy-led motivational programme to increase physical activity and improve cardiometabolic risk in people with major mental illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 54:37–44

Happell B, Davies C, Scott D (2012) Health behaviour interventions to improve physical health in individuals diagnosed with a mental illness: A systematic review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 21(3):236–247

Green CA et al (2015) The STRIDE weight loss and lifestyle intervention for individuals taking antipsychotic medications: a randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry 172(1): p. 71-81

De Hert M et al (2011) Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 10(1): p. 52-77.

Wahlbeck K et al (2011) Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 199(6):453–458

Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J (2007) A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(10):1123–1131

Plana-Ripoll O et al (2020) Nature and prevalence of combinations of mental disorders and their association with excess mortality in a population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry 19(3):339–349

Crump C et al (2013) Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 170(3):324–33

Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2014) Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10(1):425–448

Liu NH et al (2017) Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry : Official J World Psychiatr Assoc (WPA) 16(1):30–40

Olfson M et al (2015) Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72(12):1172–81

Firth J et al (2019) The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 6(8):675–712

Hennekens CH et al (2005) Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J 150(6):1115–21

Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND (2020) Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry 20(1):124–130

Ghoneim S et al (2020) The incidence of COVID-19 in patients with metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a population-based study. Metabolism Open 8:100057

Bansal R, Gubbi S, Muniyappa R (2020) Metabolic syndrome and COVID 19: endocrine-immune-vascular interactions shapes clinical course. Endocrinology 161(10)

Williamson EJ et al (2020) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584(7821):430–436

Anderson MR, Geleris J, Anderson DR, Zucker J, Nobel YR, Freedberg D, Small-Saunders J, Rajagopalan KN, Greendyk R, Chae SR, Natarajan K, Roh D, Edwin E, Gallagher D, Podolanczuk A, Barr RG, Ferrante AW, & Baldwin MR (2020) Body mass index and risk for intubation or death in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 173:782-790

Mitchell AJ et al (2013) Is the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull 39(2):295–305

Mitchell AJ et al (2013) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 39(2):306–18

McCreadie RG (2003) Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry 183:534–9

Jørgensen M et al (2018) Quality and predictors of diabetes care among patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide study. Psychiatr Serv 69(2): p. 179-185

Nasrallah HA et al (2006) Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res 86(1):15–22

Laursen TM et al (2014) Cardiovascular drug use and mortality in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a Danish population-based study. Psychol Med 44(8):1625–37

Nordentoft M et al (2013) Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS One 8(1):e55176

Kugathasan P et al (2020) Association of physical health multimorbidity with mortality in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: using a novel semantic search system that captures physical diseases in electronic patient records. Schizophr Res 216:408–415

Stubbs B et al (2016) Physical multimorbidity and psychosis: comprehensive cross sectional analysis including 242,952 people across 48 low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med 14(1):189

Lydon A et al (2020) Routine screening and rates of metabolic syndrome in patients treated with clozapine and long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications: a cross-sectional study. Ir J Psychol Med p. 1-9

Stubbs B et al (2015) The prevalence and predictors of type two diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 132(2):144–157

de Leon J, Diaz FJ (2005) A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res 76(2):135–157

Dipasquale S et al (2013) The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res 47(2):197–207

Kelly JR et al (2020) The role of the gut microbiome in the development of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res

Vancampfort D et al (2017) Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 16(3):308–315

Carney R et al (2016) Cardiometabolic risk factors in young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 170(2):290–300

Gaughran F et al (2019) Effect of lifestyle, medication and ethnicity on cardiometabolic risk in the year following the first episode of psychosis: prospective cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 215(6):712–719

Pillinger T et al (2017) Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74(3):261–269

Perry BI et al (2016) The association between first-episode psychosis and abnormal glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3(11):1049–1058

Pillinger T et al (2019) Is psychosis a multisystem disorder? A meta-review of central nervous system, immune, cardiometabolic, and endocrine alterations in first-episode psychosis and perspective on potential models. Mol Psychiatry 24(6):776–794

Rajkumar AP et al (2017) Endogenous and antipsychotic-related risks for diabetes mellitus in young people with schizophrenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 174(7):686–694

Perry BI et al (2021) Longitudinal trends in childhood insulin levels and body mass index and associations with risks of psychosis and depression in young adults. JAMA Psychiatry

De Hert M et al (2009) Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry 24(6):412–24

Henderson DC et al (2015) Pathophysiological mechanisms of increased cardiometabolic risk in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. Lancet Psychiatry 2(5):452–464

Verma S et al (2009) Effect of treatment on weight gain and metabolic abnormalities in patients with first-episode psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43(9):812–7

Barton BB et al (2020) Update on weight-gain caused by antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 19(3):295–314

Teff KL et al (2013) Antipsychotic-induced insulin resistance and postprandial hormonal dysregulation independent of weight gain or psychiatric disease. Diabetes 62(9):3232–3240

O’Donoghue B et al (2020) Physical health trajectories of young people commenced on clozapine. Ir J Psychol Med p. 1-7

Leucht S et al (2013) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. The Lancet 382(9896):951–962

Zhang J-P et al (2013) Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16(6): p. 1205-1218

Pillinger T et al (2020) Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 7(1):64–77

Huhn M et al (2019) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet 394(10202):939–951

Rummel-Kluge C et al (2010) Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 123(2–3):225–33

Lieberman JA et al (2005) Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 353(12):1209–1223

Kahn RS et al (2008) Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet 371(9618):1085–97

Cooper SJ et al (2016) BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol 30(8):717–48

NICE (2014) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance, in Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Treatment and Management: Updated Edition 2014. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK)Copyright (c) National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, London

Psychiatrists RCo (2014) Second National Audit of Schizophrenia. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/ccqi/national-clinical-audits/national-clinical-audit-of-psychosis/national-audit-schizophrenia

Crawford MJ et al (2014) Assessment and treatment of physical health problems among people with schizophrenia: national cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 205(6):473–7

Psychiatrists RCo (2012) National Audit of Schizophrenia (NAS). Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/ccqi/national-clinical-audits/national-clinical-audit-of-psychosis/national-audit-schizophrenia

Shiers D, Bradshaw T, Campion J (2015) Health inequalities and psychosis: time for action. Br J Psychiatry 207(6):471–473

Shiers D et al (2014) Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource: an intervention framework for patients with psychosis and schizophrenia. Royal College of Psychiatrists, London

Taylor DM, Gaughran F, Pillinger T (2020) The Maudsley Practice Guidelines for Physical Health Conditions in Psychiatry

Psychiatrists RCo (2019) National clinical audit of psychosis – National Report for the Early Intervention in Psychosis Spotlight Audit 2018/2019. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/NCAP

Pearsall R et al (2019) Health screening, cardiometabolic disease and adverse health outcomes in individuals with severe mental illness. B J Psych open 5:e97. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.76

Thompson A et al (2011) Targeted intervention to improve monitoring of antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic disturbance in first episode psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 45(9):740–8

O’Callaghan C et al (2011) Screening for metabolic syndrome in long-term psychiatric illness: audit of patients receiving depot antipsychotic medication at a psychiatry clinic. Eur J Psychiatry 25:213–222

Murtagh A et al (2011) Improving monitoring for metabolic syndrome using audit. Ir J Psychol Med 28(3):1–4

Barnes TRE et al (2015) Screening for the metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication: findings of a 6-year quality improvement programme in the UK. BMJ Open 5(10):e007633

Gallagher D et al (2013) A health screening and promotion clinic to improve metabolic monitoring for patients prescribed antipsychotic medication. Ir J Psychol Med 30(2):113–118

Michael S, MacDonald K (2020) Improving rates of metabolic monitoring on an inpatient psychiatric ward. BMJ Open Quality 9(3):e000748

Mouko J, Sullivan R (2017) Systems for physical health care for mental health patients in the community: different approaches to improve patient care and safety in an Early Intervention in Psychosis Service. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 6(1)

Ireland, H.N.W.G.a.C.A.G.o.C.o.P.o (2019) HSE national clinical programme for early intervention in psychosis - model of care. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/about/Who/cspd/ncps/mental-health/

Vasudev K, Martindale BV (2010) Physical healthcare of people with severe mental illness: everybody’s business! Ment Health Fam Med 7(2):115–22

Bonfioli E et al (2012) Health promotion lifestyle interventions for weight management in psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry 12:78

Shannon A et al (2020) A systematic review of the effectiveness of group-based exercise interventions for individuals with first episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res 293:113402

Fouhy F, Cullen W, O’Connor K (2020) Physical health interventions for patients who have experienced a first episode of psychosis: a narrative review. Ir J Psychol Med p. 1-14

O’Donoghue B et al (2020) Physical health assistance in early recovery of psychosis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Early Interv Psychiatry 14(5):587–593

Morrison AP et al (2020) Antipsychotic medication versus psychological intervention versus a combination of both in adolescents with first-episode psychosis (MAPS): a multicentre, three-arm, randomised controlled pilot and feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry

Kane John M et al (2016) Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry 173(4):362–372

Horowitz MA, Murray RM, Taylor D (2020) Tapering antipsychotic treatment. JAMA Psychiatry

Nguyen T et al (2020) The effect of Clinical Practice Guidelines on prescribing practice in mental health: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res 284:112671

Kelly J et al (2014) The impact of a change in prescribing policy on antipsychotic prescribing in a general adult psychiatric hospital. Ir J Psychol Med 31(3):167–173

Kelly J et al (2015) The impact of a change in prescribing policy on antipsychotic prescribing in a general adult psychiatric hospital. Ir J Psychol Med 32(4):361–363

Nguyen T et al (2020) Reduction in the prescription of Olanzapine as a first-line treatment for first episode psychosis following the implementation of clinical practice guidelines. Schizophr Res 215:469–470

Keating D et al (2021) Prescribing pattern of antipsychotic medication for first-episode psychosis: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 11(1):e040387

American Diabetes Association APA, Endocrinologists AAoC, Obesity NAAftSo (2004) Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Obes Res 12(2): p. 362-368

Sinnott M et al (2015) Fasting plasma glucose as initial screening for diabetes and prediabetes in Irish adults: the Diabetes Mellitus and Vascular Health Initiative (DMVhi). PLoS One 10(4):e0122704

Ireland IoPHi (2010) Hypertension briefing. Available from: http://www.publichealth.ie/sites/default/files/Hypertension%20Briefing%2015%20May%202012%20FINAL.pdf

McCombe G et al (2019) Key worker-mediated enhancement of physical health in first episode psychosis: protocol for a feasibility study in primary care. JMIR Res Protoc 8(7):e13115–e13115

Fogarty F et al (2020) Physical health among patients with common mental health disorders in primary care in Europe: a scoping review. Ir J Psychol Med p. 1-17

Health Df (2013) e-Health strategy for Ireland. Available from: https://www.ehealthireland.ie/Strategic-Programmes/Electronic-Health-Record-EHR

Firth J et al (2016) Mobile phone ownership and endorsement of “mHealth” among people with psychosis: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Schizophr Bull 42(2):448–455

Torous J et al (2019) Towards a consensus around standards for smartphone apps and digital mental health. World Psychiatry: Official J World Psychiatr Assoc (WPA) 18(1):97–98

Muralidharan A et al (2018) Impact of online weight management with peer coaching on physical activity levels of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 69(10):1062–1068

Macias C et al (2015) Using smartphone apps to promote psychiatric and physical well-being. Psychiatr Q 86(4):505–19

Hoffman L et al (2020) Digital Opportunities for Outcomes in Recovery Services (DOORS): a pragmatic hands-on group approach toward increasing digital health and smartphone competencies, autonomy, relatedness, and alliance for those with serious mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract 26(2): p. 80-88

Vaidyam AN et al (2019) Chatbots and conversational agents in mental health: a review of the psychiatric landscape. Can J Psychiatr 64(7):456–464

Tréhout M et al (2020) A web-based adapted physical activity program (e-APA) versus health education program (e-HE) in patients with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (PEPSY V@Si). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The SJH/AMNCH Research Ethics Committee deemed this project an audit, and therefore, there were no ethical issues.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, J.R., Gounden, P., McLoughlin, A. et al. Minding metabolism: targeted interventions to improve cardio-metabolic monitoring across early and chronic psychosis. Ir J Med Sci 191, 337–346 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02576-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02576-5