Notes

The term ‘Michurinism’ referred to a hero of Soviet agriculture, I. V. Michurin (1855–1935), who was recognized as an important plant breeder by Soviet authorities. His closest analogue would be Luther Burbank in the US (1849–1946); however unlike Burbank, none of Michurin’s innovations are cultivated today.

The earliest use of ‘Lysenkoism’ in English dates from 1945, when it was invoked in a discussion about the autonomy of science after the Second World War—the moment when researchers in the US were waking up to the dangers and opportunities presented by the increased interest of the government in their work. The term Lysenkovschina was coined about a decade later in Russia as part of the first wave of criticism of Lysenko following the death of Stalin. The suffix ‘-schina’ is also attached to other names in Russia besides Lysenko’s. It denotes the politicization of an individual’s public image and ideas. It is also worth noting that though ‘Lysenkovschina’ appears in the Russian version of Wikipedia, ‘Lysenkoism’ does not. For a definition of the latter term one must consult a dictionary. See . The word is also spelled in English as ‘Lysenkovshchina’—however I have chosen the version without the ‘h’ between the ‘s’ and ‘c’ for the sake of simplicity and the fact that even Lysenko’s name is often pronounced quite differently depending upon who is talking about him.

The most prominent was Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943), whom Haldane met when he visited the USSR in 1932 (for details of the visit see Charlotte Haldane’s Truth will out (Haldane 1950, pp. 41–42)). For a comprehensive list of the scientists and politicians who were victims of this period, see Joravsky (1970, pp. 317–335); for an account of the history of famine in Russia, with an emphasis on the Soviet period, see the following description and list of sources published by Mark Tauger: https://www.newcoldwar.org/archive-of-writings-of-professor-mark-tauger-on-the-famine-scourges-of-the-early-years-of-the-soviet-union/.

It is worth noting that this essay was left out of the edition of Possible worlds published in the US.

‘J.B.S. Haldane’s self-obituary,’ The Listener, 10 December 1964, pp. 934–935.

J. B. S. Haldane to Maya (Louisa Kathleen Haldane), 29 March 1915 (MS-374-12. Mf. Sec. MSS. 2103. MS. 20665. Haldane Papers, National Library of Scotland).

According to Haldane’s sister Naomi Mitchison, the family was never thanked for their work on the gas mask due to a political scandal involving their uncle, Richard Haldane, who was blamed for having been naïve about Germany’s preparations for war when he served as British War Minister from 1905 to 1912. See Mitchison’s All change here (Mitchison 1988, pp. 112–113), as well as numerous references to Lord Haldane in The Times of London, from January 1915 through December 1918.

Cock and Forsdyke (2008).

Cock and Forsdyke (2008, p. 289).

Cock and Forsdyke (2008, p. 376).

Haldane et al. (1915).

Cock and Forsdyke (2008, pp. 337–338). Correspondence: Naomi Mitchison to J. B. S. Haldane, Thursday the 23rd[1915?] (J. B. S. Haldane Papers, National Library of Scotland); J. B. S. Haldane to Naomi Haldane, undated (Acc. 1075 3/1, Haldane Papers, National Library of Scotland); Naomi Mitchison Correspondence, 1915–1917, 1967–1970 (Haldane Papers. National Library of Scotland). It is ironic that Bateson accepted their paper given that its significance was showing genetic linkage, which was the precise reason he had rejected Sturtevant’s paper the year before.

Correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to Naomi Mitchison, 31 March 1915 (MS-374-12. Mf. Sec. MSS. 2103. MS. 20665. Haldane Papers National Library of Scotland).

Callinicus (Haldane 1925, pp. 5–6).

Aldous Huxley’s Antic hay (Huxley 1997, pp. 55, 58, 60 and 94); the first edition was published in 1923, the same year Haldane published Daedalus.

See bibliography items 1924a, 1924b, 1925d, 1926a, 1927a, 1927b, 1931a, 1931b, 1932c. in Pirie (1966). For the connection between Haldane’s work and Drosophila genetics, see, among other primary sources: Dobzhansky (1937, pp. 124, 174, 176, 177 and 252) (the number of references to Haldane is particularly notable in light of the fact that Dobzhansky was much more attracted to Sewall Wright’s mathematics of population genetics than he was to Haldane’s or Ronald Fisher’s); Lewontin et al. (2003, pp. 56–63).

Another very early example of Haldane’s antipathy towards the US is an undated letter sent to his sister Naomi between 1916 and 1928, where he congratulated her on being published in the US by saying: ‘I am glad you are being translated into American. I don’t remember anything worse than TONGUES.’ (Acc. 9186/2, Naomi Mitchison Correspondence, 1916–1928, n.d. Haldane Papers, National Library of Scotland).

It is not only ironic that Haldane used his first opportunity to publish popular articles in the US to insult the US, but then he also ignored his deal with Forum to give them first option on his work (Correspondence, Managing Editor to Mrs C. Burghes, 25 January 1926. MS-374-12. Mf. Sec. MSS. 2103. Ms. 20665. National Library of Scotland).

Haldane (1926).

Muller (1932, see pages 40 and 45).

‘Dr. Haldane on Eugenics’, New York Herald Tribune, 23 August 1932.

American Museum of Natural History Library Central Archives, Box 737, Folder ‘International Congress of Genetics 1932’, 1267. Muller’s behaviour towards Haldane at this point was most likely due to the fact that he thought, because they were both socialists, they had much more in common than they did. Another factor is that Muller had so few allies at this point due to his reputation for alienating people by accusing them of taking credit for his work. See Carlson (1981) as well as comprehensive histories of the Fly Room such as Kohler (1994) and Allen (1978).

Evidence that Muller considered the USSR his new home and did not plan on returning as a citizen to the US includes trivial details such as that he let his auto insurance as well as his membership in the American Society of Zoologists expire, to broader evidence such as that the reason he never joined the Communist Party in the US was because he believed it would hurt his chances of being able to resettle in the Soviet Union. Also, in the letter Muller wrote to Stalin hoping to sell him on his eugenics plan, as outlined in Out of the night (Muller 1935), he predicted that the army that would be bred as a result could easily conquer capitalism. See Correspondence, The Robbins Company to Mr Muller, 17 February 1934 (Muller Correspondence, 1933–1934. Muller MSS. Series I Box 1, LMC1899, Lilly Library, Indiana University). Correspondence, H. B. Goodrich to Dr Muller, 9 January 1935; correspondence, Carlos Offermann to Elof Axel Carlson, undated (Hermann J. Muller Papers. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives). For Muller’s letter to Stalin see Subseries: Writings by Muller (Box I. Muller Papers, Lilly Library, Indiana University).

Correspondence, H. J. Muller to Julian Huxley, 9 March 1937 (Huxley, J. S. 1933–1937. Muller MSS. Series I, Box 23. Lilly Library, Indiana University); see also deJong-Lambert (2013).

See deJong-Lambert (2017).

The notes on these experiments can be found in the J. B. S. Haldane papers at the National Library of Scotland. Among the best examples of what Haldane subjected himself to can be found in MS20566-73, ‘Third trial of proposed helium-breathing apparatus’ (J. B. S. Haldane Papers. National Library of Scotland). For accounts of the effect of these experiments upon Haldane’s health see Montagu (1970, pp. 234–238) and Sheridan (1986, p. 87).

Haldane (1940, p. 83).

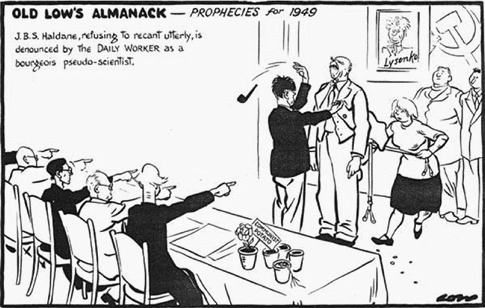

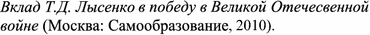

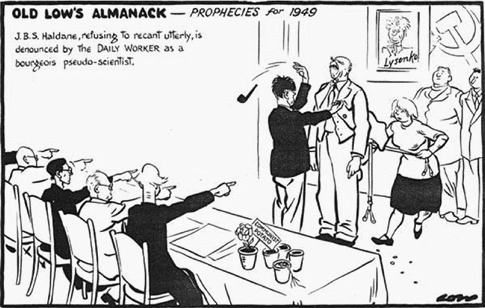

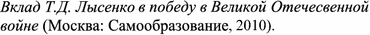

Lysenko’s wartime activities remain a relatively understudied topic. One recent investigation is Hirofumi Saito, ‘T. D. Lysenko and VASKhNIL during wartime: The “Pre”-History of the August Session of 1948’ (unpublished presentation, 7th International Conference of the European Society for the History of Science, 24 September 2016). Saito’s account challenges the idea that Lysenko’s agricultural proposals were widely adopted and proved useful during this period, as well as that this success was a factor in his assuming the presidency of VASKhNIL after the war. For an example of the type of account Saito is opposing, see P. F. Kononkov (2010)

Lysenko (1946); J. B. S. Haldane to H. J. Muller, 15 May 1946 (Haldane 1932–1964. Muller MSS. Series I Box 21, Lilly Library, Indiana University); H. J. Muller to Milislav Demerec, 5 June 1946 (Milislav Demerec Papers, The American Philosophical Society).

The letters outlining these arrangements can be found in exchanges between Haldane and Dr Komarek, Dr A. Hoffmeister, B. Fogarasi, Dr E. Weil and Mr Ferencz, dating between 23 January 1947 and 29 July 1948 (MS20535 (132−139), MS20534 (181a−191), MS20534 (202−211), MS20535 (22−30b), MS20535 (40−47), MS20535 (48−55), MS20535 (56−64), MS20535 (83−92), J. B. S. Haldane Papers, National Library of Scotland). The letter where Haldane cancelled his trip is undated, but given the order of the letters must have been sent after the VASKhNIL conference.

Correspondence, Theodosius Dobzhansky to L. C. Dunn, 8 January 1947 (The American Philosophical Society); correspondence, Theodosius Dobzhansky to L. C. Dunn, 23 January 1947 (The American Philosophical Society).

‘Scientists Choice’, Time, 27 September 1948.

Correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to Dr Komarek, undated (MS20535 (132−139), J. B. S. Haldane Papers, National Library of Scotland).

H. J. Muller to Milislav Demerec, 5 June 1946 (Milislav Demerec Papers, The American Philosophical Society).

‘The Lysenko Controversy’, The Listener, 9 December 1948, p. 875; Naomi as well was bothered by the fact that what was advertised as a debate actually consisted of four geneticists separately recording their opinions for live broadcast, rather than an actual conversation between them. As she wrote to her brother the next day, ‘The broadcast last night was very interesting though it would have been much more worthwhile if you could all have seen one another’s scripts’ (Naomi Mitchison to J. B. S. Haldane, undated. Haldane Box 15 (b). Lysenko Controversy, 1947–1950. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London).

Langdon-Davies (1949). Langdon-Davies’ claim—that the reason Darlington, Fisher and Harland had been recorded separately was because, ‘[t]he BBC took special precautions against possible murder by having each of the four conspirators record contributions under circumstances which insured against their meeting on the stairs’—speaks for itself (Langdon-Davies 1949, p. 78). It is also notable that both Langdon-Davies and Muller are accused of politicizing biological science during this period by those who seek to restore Lysenko’s reputation in Russia today. See

Langdon-Davies (1949, pp. 155, 12–13).

David Low, The Evening Standard, c. 1949. The Daily Worker was published by the British Communist Party and Haldane was a regular contributor between 1937 and 1950. The same month as the BBC debate Haldane also published a letter in The Hindu defending himself against the accusation that he was unable to express his true thoughts on Lysenko because no ‘progressive paper’ would publish them. Once Langdon-Davies’s Russia puts the clock back came out Haldane again published a letter in The Hindu where he stated that he had ‘seldom read a book containing more demonstrably untrue statements in so short a space’. See ‘Lysenko and Darwin’, The Hindu, 19 December 1948 and ‘Nonsense About Lysenko’, The Hindu, 20 November 1949; thanks to Veena Rao for bringing both these articles to my attention. For a different perspective, both on Haldane’s attitude in the matter of Lysenko and on the BBC radio ’debate’ alluded to earlier, see the accompanying article by Charlesworth (2017).

Correspondence, Judith Todd to J. B. S. Haldane, 30 May 1951 (Haldane Box 34. 4 (1946–1951). J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to Judith Todd, 1 June 1951 (Haldane Box 34. 4 (1946–1951). J. B .S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, Dr Barnett Stross to J. B. S. Haldane, 26 March 1952 (Haldane Box 21. General correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to Dr Barnett Stross, 27 March 1952 (Haldane Box 21. General Correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, Stephen Joley to J. B. S. Haldane, 22 May 1952 (Haldane Box 21. General correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to Stephen Joley, 4 June 1952 (Haldane Box 21. General correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to the Private Secretary, The Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, undated (Haldane Box 21. General Correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to the Private Secretary, 1 October 1952 (Haldane Box 21. General correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London). An extremely insightful account of the difficulty of Haldane’s position during these years can be found in an interview with John Maynard Smith; see http://www.webofstories.com/play/john.maynard.smith/33; thanks very much to Vidyanand Nanjundiah for making me aware of this reference.

Correspondence, Francis Harwain to J. B. S. Haldane, 24 December 1947 (Haldane Box 34. 4 (1946–1951). J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London); correspondence, J. B. S. Haldane to Ruth Moore, 18 March 1952 (Haldane Box 21. General Correspondence, 1951–1952. J. B. S. Haldane Papers, University College London).

‘Haldane, Geneticist, Quits Britain for India Which Has No G.I.’s’, The New York Times, 25 July 1957.

Medvedev (1969, p. 225).

The exact ‘crime’ Lysenko was ultimately accused of was misrepresenting butterfat yields among his cows at his experimental station in the Lenin Hills outside Moscow. In context with the larger consequences of Lysenko’s career, his denouement was trivial.

References

Allen G. E. 1978 Thomas Hunt Morgan, the man and his science. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Carlson E. A. 2001 Genes, radiation and society: the life and work of H.J. Muller, pp. 178–179. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Carlson E. A. 2001 The unfit: a history of a bad idea. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor.

Charlesworth B. 2017 Haldane and modern evolutionary genetics. J. Genet. 96, (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12041-017-0833-4).

Clark R. W. 1969 J. B. S.: the life and work of J. B. S. Haldane. Coward-McCann, New York.

Cock A. G. and Forsdyke D. R. 2008 Treasure your exceptions: the science and life of William Bateson. Springer, New York.

Davenport C. B. 1930 Sex linkage in man. Genetics 15, 401–444.

deJong-Lambert W. 2017 H. J. Muller and J. B. S. Haldane: eugenics and Lysenkoism. In The Lysenko controversy as a global phenomenon (ed. W. deJong-Lambert and N. Krementsov), vol. II. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

deJong-Lambert W. and Krementsov N. 2012 On labels and issues: the Lysenko controversy and the Cold War. J. Hist. Biol. 45, 373–388.

deJong-Lambert W. 2013 Why did J. B. S. Haldane defend T. D. Lysenko? Oxford Magazine 340, 10–14.

deJong-Lambert W and Krementsov N (ed.) 2017 The Lysenko controversy as a global phenomenon (in two volumes). Palgrave Macmillan, London (publication forth coming).

Dobzhansky T. G. 1937 Genetics and the origin of species. Columbia University Press, New York.

Haldane C. 1950 Truth will out. Vanguard Press, New York.

Haldane J. B. S. 1925 Callinicus: a defence of chemical warfare. E. P. Dutton, New York.

Haldane J. B. S. 1926 Nationality and research. Forum 718–723.

Haldane J. B. S. 1932 The inequality of man and other essays. Chatto and Windus, London.

Haldane J. B. S. 1935 The rate of spontaneous mutation of a human gene. J. Genet. 31, 317–326.

Haldane J. B. S. 1938 Heredity and politics. W.W. Norton, New York.

Haldane J. B. S. 1940 Science in peace and war. Lawrence and Wishart, London.

Haldane J. B. S., Sprunt A. D. and Haldane N. M. 1915 Reduplication in mice. J. Genet. 5, 133.

Haldane L. K. 1961 Friends and kindred: memoirs of Louisa Kathleen Haldane. Faber and Faber, London.

Huxley A. L. 1997 Antic hay. Dalkey Archive Press, London.

Joravsky D. 1970 The Lysenko affair. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Kevles D. J. 1985 In the name of eugenics: genetics and the uses of human heredity. University of California Press, California

Kohler R. E. 1994 Lords of the fly: Drosophila genetics and the experimental life. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Krementsov N. 2004 International science between the wars: the case of genetics. Routledge, New York.

Langdon-Davies J. E. 1949 Russia puts the clock back: Langdon-Davies versus Haldane. Victor Gollancz, London.

Lewontin R. C., Moore J. A., Provine W. B. and Wallace B. (ed.) 2003 Dobzhansky’s genetics of natural populations, I–XLIII. Columbia University Press, New York.

Lysenko T. D. 1949 Heredity and its variability, transl. Theodosius Dobzhansky. King’s Crown Press, New York.

Medvedev Z. A. 1969 The rise and fall of T. D. Lysenko. Columbia University Press, New York.

Mitchison N. 1988 All change here. Richard Drew Publishing, Glasgow.

Montagu I. 1970 The youngest son: autobiographical sketches. Lawrence and Wishart, London.

Muller H. J. 1932 The dominance of economics over eugenics. The Scientific Monthly, 371, 40–47.

Muller H. J. 1935 Out of the night: a biologist’s view of the future. Vanguard Press, New York (several later editions).

Pirie N. W. 1966 John Burdon Sanderson Haldane. 1892-1964. Biogr. Mem. Fellows R. Soc. 12: 219–249.

Sheridan D. (ed.) (1986) Among you taking notes: the wartime diary of Naomi Mitchison, 1939–1945. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Soyfer V. N. 2003 Tragic history of the VII international congress of genetics. Genetics 165, 1–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dejong-Lambert, W. J. B. S. Haldane and ЛысеHкOвщиHа (Lysenkovschina). J Genet 96, 837–844 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12041-017-0843-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12041-017-0843-2