Abstract

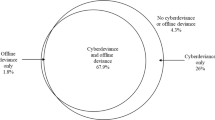

Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) general theory of crime and Akers’ (1998) social learning theory have received strong empirical support for explaining crime in both the physical and cyberworlds. Most of the studies examining cybercrime, however, have only used college samples. In addition, the evidence on the interaction between low self-control and deviant peer associations is mixed. Therefore, this study examined whether low self-control and deviant peer associations explained various forms of cyberdeviance in a youth sample. We also tested whether associating with deviant peers mediated the effect of low self-control on cyberdeviance as well as whether it conditioned the effect. Low self-control and deviant peer associations were found to be related to cyberdeviance in general, as well as piracy, harassment, online pornography, and hacking specifically. Deviant peer associations both mediated and exacerbated the effect of low self-control on general cyberdeviance, though these interactions were not found for the five cyberdeviant types examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We focused on the work of Higgins (2007) and Gibson et al. (2010) because they examined the construct validity of the original Grasmick et al. scale with four options ranging from strongly agree to strong disagree. Piquero, MacIntosh, and Hickman (2000) tested a revised version of the Grasmick et al. scale that had five options measuring how frequent someone acted in that fashion.

Pirating media, pirating software, and viewing offensive sexual materials online were measured with the following three items respectively: 1) knowingly used, made, or gave to another person “pirated” media (music, television show, or movie); 2) knowingly used, made, or gave to another person a “pirated” copy of commercially-sold computer software; 3) looked at pornographic, obscene, or offensive materials online. Peer harassment was computed by taking the average of the standardized scores for the following four measures (alpha = .919): 1) posted or sent a message about someone for other people to see that made that person feel bad; 2) posted or sent a message about someone for other people to see that made that person feel threatened or worried; 3) sent a message to someone via e-mail or instant message that made that person feel threatened or worried; and 4) sent a message to someone via e-mail or instant message that made that person feel bad. Peer computer hacking was created by averaging the standardized scores for the following three items (alpha = .832): 1) tried to guess another’s password to get into his/her computer account or files; 2) accessed another’s computer account or files without his/her knowledge or permission just to look at the information or files; and 3) added, deleted, changed or printed any information in another’s computer files without the owner’s knowledge or permission.

There are two statistically significant differences (Paternoster et al., 1998) between the three self-control measures in Model 2. First, the Gibson measure had a statistically significant stronger effect on cyberdeviance (b = .009; std. error = .001). Second, a statistically significant mediation effect is found in Model 2 when using the traditional Grasmick et al. scale and the Gibson scale, but not the Higgins scale. The standard error for low self-control using the Higgins scale is .002 rather than .001 as is found for the other two measurements.

In order to further verify this conclusion, a linear regression was conducted with peer deviance as the dependent variable (results not shown). This model indicated that low self-control, spending more time online for non-school related reasons, computer skill, and lower report card grades all increased the association with delinquent others.

Although there were no statistically significant differences between the three different measures of low self-control within the two subgroups, the Gibson et al. measure indicated a conditioning effect (z = −3.13), congruent with that of the unstandardized scale. The Higgins measure had no such effect (z = −1.58), though this was because of the larger standard errors.

We dichotomized the components because of heavy skew and little variation. Most students did not commit these offenses or performed them at lower levels (see descriptives Table 1). Therefore, we dichotomized software piracy, pornography, harassment, and computer hacking (0 = no; 1 = yes) in order to examine whether self-control predicted the probability of committing these acts. Media piracy (mean = 1.29; std. dev. = 2.05) was a partial exception to the trend, as 55.9% of the sample did not engage in this offense within the last year. Another 16.8% stated that they had pirated media once or twice in the last year. This total (72.7%) is similar to the percentages of students who had not committed any of the other offenses; thus we dichotomized media piracy based on students who engaged in piracy less than twice in the last 12 months (0) and those who committed it more often (1).

Z-tests indicate that there were no significant differences in the abilities of the Grasmick et al., Higgins, and Gibson scales in predicting the five types of cyberdeviance.

Since the individual peer deviance measures were five-point ordinal measures, we could not partition the models by medians. Instead, we partitioned on whether or not the person had deviant peer associations for that specific item (i.e. low = 0; high = all other options).

References

Akers, R. L. (1998). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Akers, R. L., & Jensen, G. F. (2006). The empirical status of social learning theory of crime and deviance: The past, present, and future. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (pp. 37–76). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Akers, R. L., & Lee, G. (1996). A longitudinal test of social learning theory: Adolescent smoking. Journal of Drug Issues, 26, 317–343.

Bocij, P. (2004). Cyberstalking: Harassment in the internet age and how to protect your family. Westport: Praeger.

Boeringer, S., Shehan, C. L., & Akers, R. L. (1991). Social contexts and sexual learning in sexual coercion and aggression: Assessing the contribution of fraternity membership. Family Relations, 40, 558–564.

Bossler, A. M., & Burruss, G. W. (2010). The general theory of crime and computer hacking: Low self-control hackers? In T. J. Holt & B. Schell (Eds.), Corporate hacking and technology-driven crime: Social dynamics and implications (pp. 57–81). Hershey: IGI Global.

Bossler, A. M., & Holt, T. J. (2010). The effect of self-control on victimization in the cyberworld. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 227–236.

Brownfield, D., & Sorenson, A. (1993). Self-control and juvenile delinquency: Theoretical issues and an empirical assessment of selected elements of a general theory of crime. Deviant Behavior, 14, 243–264.

Buzzell, B., Foss, D., & Middleton, Z. (2006). Explaining use of online pornography: A test of self-control theory and opportunities for deviance. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 13, 96–116.

Chapple, C. L. (2005). Self-control, peer relations, and delinquency. Justice Quarterly, 22, 89–106.

DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. (2008). The Gottfredson-Hirschi critiques revisited: Reconciling self-control theory, criminal careers, and career criminals. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52, 520–537.

DiMarco, H. (2003). The electronic cloak: Secret sexual deviance in cybersociety. In Y. Jewkes (Ed.), Dot.cons: Crime, deviance, and identity on the internet (pp. 53–67). Portland: Willan Publishing.

Edleman, B. (2009). Red light states: Who buys online adult entertainment? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, 209–220.

Evans, T. D., Cullen, F. T., Burton, V. S., Jr., Dunaway, R. G., & Benson, M. L. (1997). The social consequences of self-control: Testing the general theory of crime. Criminology, 35, 475–501.

Finn, J. (2004). A survey of online harassment at a university campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 468–483.

Furnell, S. (2002). Cybercrime: Vandalizing the information society. Boston: Addison Wesley.

Gibson, C. L., Ward, J. T., Wright, J. P., Beaver, K. M., & Delisi, M. (2010). Where does gender fit in the measurement of self-control? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 883–903.

Gibson, C., & Wright, J. (2001). Low self-control and coworker delinquency: A research note. Journal of Criminal Justice, 29, 483–492.

Gopal, R., Sanders, G. L., Bhattacharjee, S., Agrawal, M., & Wagner, S. (2004). A behavioral model of digital music piracy. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 14, 89–105.

Gottfredson, M. R. (2006). The empirical status of control theory in criminology. In F. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (pp. 77–100). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1987). The methodological adequacy of longitudinal research on crime. Criminology, 25, 581–614.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Grasmick, H. G., Tittle, C. R., Bursik, R. J., Jr., & Arneklev, B. J. (1993). Testing the core empirical implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 30, 5–29.

Higgins, G. E. (2005). Can low self-control help with the understanding of the software piracy problem? Deviant Behavior, 26, 1–24.

Higgins, G. E. (2006). Gender differences in software piracy: The mediating roles of self-control theory and social learning theory. Journal of Economic Crime Management, 4, 1–30.

Higgins, G. E. (2007). Examining the original Grasmick scale: A Rasch model approach. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34, 157–178.

Higgins, G. E., Fell, B. D., & Wilson, A. L. (2006). Digital piracy: Assessing the contributions of an integrated self-control theory and social learning theory using structural equation modeling. Criminal Justice Studies, 19, 3–22.

Higgins, G. E., Fell, B. D., & Wilson, A. L. (2007). Low self-control and social learning in understanding students’ intentions to pirate movies in the United States. Social Science Computer Review, 25, 339–357.

Higgins, G. E., & Makin, D. A. (2004a). Does social learning theory condition the effects of low self-control on college students’ software piracy. Journal of Economic Crime Management, 2, 1–21.

Higgins, G. E., & Makin, D. A. (2004b). Self-control, deviant peers, and software piracy. Psychological Reports, 95, 921–931.

Higgins, G. E., & Wilson, A. L. (2006). Low self-control, moral beliefs, and social learning theory in university students’ intentions to pirate software. Security Journal, 19, 75–92.

Higgins, G. E., Wolfe, S. E., & Marcum, C. D. (2008). Digital piracy: An examination of three measurements of self-control. Deviant Behavior, 29, 440–460.

Hinduja, S. (2001). Correlates of internet software piracy. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 17, 369–382.

Hinduja, S., & Ingram, J. R. (2008). Self-control and ethical beliefs on the social learning of intellectual property theft. Western Criminology Review, 9, 52–72.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2008). Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior, 29, 129–156.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2009). Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Holt, T. J. (2007). Subcultural evolution? Examining the influence of on- and off-line experiences on deviant subcultures. Deviant Behavior, 28, 171–198.

Holt, T. J., & Bossler, A. M. (2009). Examining the applicability of lifestyle-routine activities theory for cybercrime victimization. Deviant Behavior, 30, 1–25.

Holt, T. J., Burruss, G. W., Bossler, A. M. (2010). Social learning and cyber deviance: Examining the importance of a full social learning model in the virtual world. Journal of Crime and Justice 33, page numbers not assigned yet

Ingram, J. R., & Hinduja, S. (2008). Neutralizing music piracy: An empirical examination. Deviant Behavior, 29, 334–366.

Jordan, T., & Taylor, P. (1998). A sociology of hackers. The Sociological Review, 46, 757–780.

Krohn, M. D. (1999). Social learning theory: The continuing development of a perspective. Theoretical Criminology, 3, 462–475.

Lane, F. S. (2000). Obscene profits: The entrepreneurs of pornography in the cyber age. New York: Routledge.

Lee, G., Akers, R. L., & Borg, M. J. (2004). Social learning and structural factors in adolescent substance use. Western Criminology Review, 5, 17–34.

Longshore, D., Chang, E., Hsieh, S., & Messina, N. (2004). Self-control and social bonds: A combined control perspective on deviance. Crime & Delinquency, 50, 542–564.

Mason, W. A., & Windle, M. (2002). Gender, self-control, and informal control in adolescence: A test of three models of the continuity of delinquent behavior. Youth and Society, 33, 479–514.

Meldrum, R. C., Young, J. T. N., & Weerman, F. M. (2009). Reconsidering the effect of self-control and delinquent peers: Implications of measurement for theoretical significance. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 46, 353–376.

Moon, B., McCluskey, J. D., & McCluskey, C. P. (2010). A general theory of crime and computer crime: An empirical test. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 767–772.

Morris, R. G., & Higgins, G. E. (2010). Criminological theory in the digital age: The case of social learning theory and digital piracy. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 470–480.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36, 859–866.

Piquero, A. R., MacIntosh, R., & Hickman, M. (2000). Does self-control affect survey response? Applying exploratory, confirmatory, and item response theory analysis to Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale. Criminology, 38, 897–929.

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2000). The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: A meta-analysis. Criminology, 38, 931–964.

Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. T., Sellers, C. S., Winfree, L. T., Madensen, T., Daigle, L. E., et al. (2009). The empirical status of social learning theory: A meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 27, 765–802.

Rogers, M. K. (2001). A social learning theory and moral disengagement analysis of criminal computer behavior: An exploratory study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Manitoba University, Canada

Skinner, W. F., & Fream, A. M. (1997). A social learning theory analysis of computer crime among college students. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 34, 495–518.

Taylor, R. W., Fritsch, E. J., Liederbach, J., & Holt, T. J. (2010). Digital crime and digital terrorism (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Tittle, C. R., Ward, D. A., & Grasmick, H. G. (2003). Gender, age, and crime/deviance: A challenge to self-control theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40, 426–453.

Wall, D. S. (2001). Cybercrimes and the internet. In D. S. Wall (Ed.), Crime and the internet (pp. 1–17). New York: Routledge.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winfree, L. T., Taylor, T. J., He, N., & Esbensen, F. (2006). Self-control and variability over time: Multivariate results using a 5-year, multisite panel of youths. Crime and Delinquency, 52, 253–286.

Wolack, J., Mitchell, K., & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Online victimization of youth: 5 years later. Washington: National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Wolfe, S. E., & Higgins, G. E. (2009). Explaining deviant peer associations: An examination of low self-control, ethical predispositions, definitions, and digital piracy. Western Criminology Review, 10, 43–55.

Yar, M. (2005). Computer hacking: Just another case of juvenile delinquency? The Howard Journal, 44, 387–399.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holt, T.J., Bossler, A.M. & May, D.C. Low Self-Control, Deviant Peer Associations, and Juvenile Cyberdeviance. Am J Crim Just 37, 378–395 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-011-9117-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-011-9117-3