Abstract

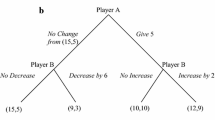

This paper considers a partial equilibrium model of conflict where two agents differently evaluate a contested stake. Differently from common contest models, agents have the option of choosing a second instrument to affect the outcome of the conflict. The second instrument is assumed to capture positive investments in ‘conflict management’—labeled as ‘talks’. The focus is on the asymmetry in the evaluation of the stake: whenever the asymmetry in the evaluation of the stake is large there is no room for cooperation and a conflict trap emerges; whenever the degree of asymmetry falls within a critical interval, cooperation seems to emerge only in the presence of a unilateral concession; as the evaluations of the stake converge, only reciprocal concessions can sustain cooperation. Finally the concept of entropy is applied to measure conflict and conflict management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On this point see Basu (2007).

Pigou (1929, pp. 202–203).

Gintis (2000, p. 262). Emphasis is in the original text. Italics turned into bold.

Boulding (1963, p. 430).

Of course, being in a partial equilibrium framework the classical tradeoff between ‘butter’ and ‘guns’ is not considered.

Following Nti (1999), under constant returns to scale in fighting, a contest with asymmetric valuations has a unique pure strategy Nash equilibrium if and only if the sum of the valuations is larger than the higher evaluation, x + δx > x.

The form adopted here is the one presented in Campiglio (1999, Chap. 4).

References

Amegashie AJ (2006) A contest success function with a tractable noise parameter. Public Choice 126:135–144

Anderton CH (2000) An insecure economy under ratio and logistic conflict technologies. J Conflict Resolut 44(6):823–838

Anderton CH, Anderton RA, Carter J (1999) Economic activity in the shadow of conflict. Econ Inq 17(1):166–179

Attaran M, Zwick M (1989) An information theory approach to measuring industrial diversification. J Econ Stud 16(1):19–30

Baik KH (1998) Difference-form contest success functions and efforts levels in contests. Eur J Polit Econ 14:685–701

Baik KH, Shogran JF (1995) Contests with spying. Eur J Polit Econ 11:441–451

Basu K (2007) Coercion, contract and the limits of the market. Soc Choice Welfare 29:559–579

Bhagwati JN (1982) Directly unproductive, profit-seeking (DUP) activities. J Polit Econ 9(5):988–1002

Boulding KE (1963) Towards a pure theory of threat systems. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 53(2):424–434

Boulding KE (1973) The economy of love and fear. Wadsworth, Belmont

Campiglio L (1999) Mercato, prezzi e politica economica. Il Mulino, Bologna

Caruso R (2005) Asimmetrie negli incentivi, equilibrio competitivo e impegno agonistico: distorsioni in presenza di doping e combine. Riv Dir Econ Sport 1(3):13–38

Caruso R (2006) Conflict and conflict management with interdependent instruments and asymmetric stakes (The Good Cop and the Bad Cop Game). Peace Econ Peace Sci Public Pol 12(1), art 1

Caruso R (2007) Continuing conflict and stalemate: a note. Econ Bull 4(17):1–8. http://economicsbulletin.vanderbilt.edu/2007/volume4/EB-07D70005A.pdf

Clark DJ, Riis C (1998) Contest success functions: an extension. Econ Theory 11:201–204

Dixit A (1987) Strategic behavior in contests. Am Econ Rev 77(5): 891–898

Dixit A (2004) Lawlessness and economics, alternative modes of governance. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Epstein GS, Hefeker C (2003) Lobbying contests with alternative instruments. Econ Gov 4:81–89

Gabor A, Gabor D (1958) L’entropie comme mesure de la liberté sociale et économique. Cahiers de l’Institut de Science Économique Appliquée, vol 72, pp 13–25

Garfinkel MR, Skaperdas S (2007) Economics of conflict: an overiew. In: Sandler T, Hartley K (eds) Handbook of defense economics, vol 22, chap 22

Gintis H (2000) Game theory evolving. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Grossman HI (1991) A general equilibrium model of insurrections. Am Econ Rev 81(4):912–921

Grossman HI (1998) Producers and predators. Pac Econ Rev 3(3):169–187

Harsanyi JC (1965) Bargaining and conflict situations in the light of a new approach to game theory. Am Econ Rev 55(1/2):447–457

Hausken K (2005) Production and conflict models versus rent-seeking models. Public Choice 123:59–93

Hillman AL, Riley JG (1989) Politically contestable rents and transfers. Econ Polit 1(1):17–39

Hirshleifer J (1988) The analytics of continuing conflict. Synthese 76(2): 201–233. Reprinted by Center for International and Strategic Affairs, CISA, University of California

Hirshleifer J (1989) Conflict and rent-seeking success functions, ratio vs. difference models of relative success. Public Choice 63:101–112

Horowitz A, Horowitz I (1968) Entropy, Markov processes and competition in the brewing industry. J Ind Econ 16:196–211

Isard W, Smith C (1982) Conflict analysis and practical management procedures. An introduction to peace science. Ballinger, Cambridge

Konrad K (2000) Sabotage in rent-seeking. J Law Econ Organ 16(1): 155–165

Nash J (1953) Two-person cooperative games. Econometrica 21(1):128–140

Neary HM (1997a) Equilibrium structure in an economic model of conflict. Econ Inq 35(3):480–494

Neary HM (1997b) A comparison of rent-seeking models and economics models of conflict. Public Choice 93:373–388

Nti KO (1999) Rent-seeking with asymmetric valuations. Public Choice 98:415–430

Nti KO (2004) Maximum efforts in contests with asymmetric valuations. Eur J Polit Econ 20:1059–1066

O’Keeffe M, Viscusi KW, Zeckhauser RJ (1984) Economic contests: comparative reward schemes. J Lab Econ 2(1):27–56

Pigou AC ([1921]1929) The economics of welfare, 3rd edn. MacMillan, London

Rosen S (1986) Prizes and incentives in elimination tournaments. Am Econ Rev 76(4):701–715

Schelling TC (1960) The strategy of conflict. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Schelling TC (1966) Arms and influence. Yale University Press, New Haven

Shannon CE, Weaver W (1949) The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

Skaperdas S (1992) Cooperation, conflict, and power in the absence of property rights. Am Econ Rev 82(4):720–739

Skaperdas S (1996) Contest success functions. Econ Theory 7:283–290

Spolaore E (2004) Economic integration, international conflict and political unions. Riv Pol Econ IX–X:3–50

Tullock G (1980) Efficient rent seeking. In: Buchanan JM, Tollison RD, Tullock G (eds) Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society. Texas A&M University, College Station, pp 97–112

Acknowledgments

This paper has been presented at the conference, Reciprocity, Theories and Facts, February 22–24, Verbania and in a seminar held at the University of Pisa where I benefited from illuminating comments. I also warmly thank Aurelie Bonein, Luigi Campiglio, Vito Moramarco, Maurizio Motolese, Carsten K. Nielsen, Johan Moyersoen, Nicola Giocoli and Davide Tondani.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

To check whether the critical points presented in (8) constitute a Nash Equilibrium I have to compute the Hessian matrices for both agents.

I start considering the payoff function of agent 1 evaluated at the critical points for agent 2, namely π rc1 (g 1, g *2 , h 1, h *2 ). It becomes:

and the Hessian matrix is given by:

Then, substitute the critical values h *1 , g *1 . The matrix becomes:

Let H 1k denote the kth order leading principal submatrix of H 1 for k = 1,2. The determinant of the kth order leading principal minor of H 1k is denoted by | H 2k |. The leading principal minors alternate signs as follows:

Then I compute the payoff function for agent 2 π rc2 (g *1 , g 2, h *1 , h 2),

and the Hessian matrix is given by:

Substitute g *2 and h *2 the matrix becomes:

Also in this case, let H 2k denote the kth order leading principal submatrix of H 2 for k = 1,2. The determinant of the kth order leading principal minor of H 2 is denoted by | H 2k |. The leading principal minors alternate in sign as follows:

Since the Hessian matrix for agent 2 is not negative semidefinite it is clear that to have an interior solution for an equilibrium the value of δ must be larger than a critical value. That is, the asymmetry in the evaluation of the stake must not be too large.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caruso, R. Reciprocity in the shadow of threat. Int. Rev. Econ. 55, 91–111 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-007-0029-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-007-0029-y

Keywords

- Conflict

- Contest

- Conflict management

- Concessions

- Reciprocity

- Asymmetry in evaluation

- Statistical entropy

- Cooperation

- Integrative systems

- ‘Guns’ and ‘talks’