Abstract

Blooms of the dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium (a.k.a.Margalefidinium) polykrikoides, have had deleterious effects on marine life across the Northern Hemisphere and, since the early 1990s, have become more frequent and widespread. While the toxic effects of C. polykrikoides have been well-described for finfish, the effects on bivalve molluscs are poorly understood, particularly in ecosystem and aquaculture settings. The purpose of this study was to characterize the comparative effects of C. polykrikoides blooms on North Atlantic bivalves and to identify the environmental factors that influence its toxic effects. The growth and survival of two age-classes (first- and second-year) of the northern quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria), the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians), and the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) were quantified in surface deployments and at depth during annual bloom events in multiple locations across eastern Long Island (NY, USA), capturing a natural gradient in C. polykrikoides. In two consecutive years, scallops deployed within surface locations experienced significant mortality (75–100%) during short-term (1–2 weeks) but intense (> 1.5 × 104 cells mL−1) C. polykrikoides blooms. Conversely, scallops deployed at depth and clams and oysters deployed at either the surface or at depth were more resistant to blooms. First-year oysters and scallops that survived blooms displayed significant reductions in growth rates, while clams and older scallops and oysters did not. Results suggest that blooms of C. polykrikoides pose significant age- and species-specific threats to native and cultured bivalve shellfish and that shellfish deployed in surface waters are at greater risk during blooms than those deployed at depth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Harmful algal blooms (HAB) pose a significant and growing threat to aquaculture (Shumway 1990; Landsberg 2010), and climate change is predicted to increase the distribution and severity of several HAB (Hallegraeff 2010; Glibert et al. 2014; Gobler et al. 2017). At bloom-exposed aquaculture locations, HAB can cause widespread (Gobler et al. 2017) mortality among cultured organisms and sub-lethal impacts (i.e., reduced growth, physical damage, etc.; Shumway 1990; Landsberg 2010; Matsuyama and Shumway, 2009; Burkholder and Shumway 2011) can limit marketability of products (Shumway 1990; Anderson et al. 2000). Certain HAB are capable of producing potent neurotoxic or gastrointestinal biotoxins that can (bio)accumulate in the tissues of exposed shellfish, and when consumed by humans can result in severe intoxication (Shumway 1990; Hégaret et al. 2009) making shellfish aquaculture particularly vulnerable to these events. As aquaculture industries continue to expand and concurrent changes in climate stimulate the growth and proliferation of certain HAB (Gobler et al. 2017), identifying potential risks (i.e., vulnerable species) and mitigation strategies may limit losses.

Identified in 1895 (Schütt 1895), blooms of dinoflagellates within the genus Cochlodinium (a.k.aMargalefidinium) have been reported along North American and East Asian coastlines for decades (Kudela and Gobler 2012). Since the 1990s, however, reports have become more commonplace with blooms now occurring in areas previously void of these HAB (Kim et al. 1999; Gobler et al. 2008; Kudela et al. 2008; Kudela and Gobler 2012). Dense aggregations of C. polykrikoides also known as, ‘rust tides,’ can be associated with widespread marine animal mortality (Kim et al. 1999; Gobler et al. 2008; Mulholland et al. 2009; Richlen et al. 2010). The toxic effects of C. polykrikoides on finfish in both field and laboratory settings have been well-described (Kim et al. 1999, 2000; Tang and Gobler 2009a) being highly lethal (Gobler et al. 2008; Tang and Gobler 2009a), manifested acutely (Kim et al. 1999; Gobler et al. 2008), and causing significant economic damage (Kim 1997; Kim et al. 1999). Shellfish are more resistant than fish to C. polykrikoides, but are nonetheless susceptible (Ho and Zubkoff 1979; Gobler et al. 2008; Tang and Gobler 2009b). While the effects of C. polykrikoides on bivalve shellfish have been described (Ho and Zubkoff 1979; Gobler et al. 2008; Tang and Gobler 2009b), there is little comparative information (i.e., species- and size-specific) and few reports describing lethal or sub-lethal effects in ecosystem settings.

Blooms of C. polykrikoides are now annual occurrences in many temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere (Gobler et al. 2008; Kudela et al. 2008; Kudela and Gobler 2012) and commonly occur in areas with widespread aquaculture within the northwest Atlantic (Gobler et al. 2008; Mulholland et al. 2009; Li et al. 2012) and Pacific (Kim et al. 1999, 2000). To date, approximately 50% of the global seafood production is aquaculture-sourced, with more than half of that production being attributed to shellfish (NMFS 2015; FAO 2016a). Within C. polykrikoides—afflicted regions of the northeastern US, bivalve shellfish represent a large and increasing portion of fisheries landings (Shumway et al. 2003; Ekstrom et al. 2015; NMFS 2015) and are a key economic resource in some coastal communities (Neiland et al. 1991; Shumway et al. 2003; Grabowski et al. 2012). In addition to their economic value, bivalve shellfish provide essential ecosystem services through the control of eutrophication (Officer et al. 1982; Dame 1996; Newell 2004; Burkholder and Shumway 2011), stabilization of coastlines (Coen et al. 2007; Grabowski and Peterson 2007), establishment of critical habitat (Tolley and Volety 2005; Coen et al. 2007; Abeels et al. 2012), and removal of particulates from the water column (Newell 2004; Wall et al. 2011).

Daily vertical movement of C. polykrikoides has been documented in Korean coastal waters (Park et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2010), with high concentrations reported at the surface during daylight hours and greater abundances at depth (< 20 m) during the night. Diel vertical migration is common in many dinoflagellate species, enabling cells to exploit nutrient-rich bottom waters in areas where surface-nutrients are depleted (Smayda and Reynolds 2003; Doblin et al. 2006). The ability of C. polykrikoides to form chains of two or more cells enhances motility (Fraga et al. 1989; Smayda and Reynolds 2003), helps to maintain surface positions in warm, low-viscosity waters (Fraga et al. 1989), and deters grazers (Jiang et al. 2009, 2010). Fish kills associated with C. polykrikoides along the east coast of Korea have been reported at depth, at night, presumably as C. polykrikoides cells migrate deeper into the water column (Kim et al. 2010). While diel movements of C. polykrikoides have been partly characterized in Asia, they have never been described along the east coast of the USA. Nonetheless, movements are likely dependent upon the hydrographic conditions in bloom-exposed areas and/or strain-specific (Kudela et al. 2008) with the ribotype (e.g., East Asian) of C. polykrikoides forming blooms in Korea being distinct from the American/Malaysian ribotype (Iwataki et al. 2008). Regardless, vertical movement within the water column could influence impacts of C. polykrikoides on aquaculture in areas where blooms are present.

The purpose of this study was to identify species-, age-, and position-specific effects of C. polykrikoides on the growth and survival of three commercially and ecologically significant bivalve shellfish, the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), the northern quahog (= hard clam; Mercenaria mercenaria), and the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians). Two age-classes of each species (first- and second-year) were deployed at bloom-prone locations in Long Island (NY, USA) estuaries at surface and bottom positions prior to and during annual bloom events in 2014 and 2015. Survival and growth of shellfish were quantified weekly as blooms initiated, peaked, and waned. In addition to quantifying growth and survival of bivalves, surface and bottom chlorophyll a, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and C. polykrikoides densities were measured at each site.

Materials and Methods

Shellfish Collection and Maintenance

To assess the age- and species-specific effects of C. polykrikoides exposure at varying vertical positions within the water column, multiple species of shellfish of different age classes (first- and second-year; all diploid) were deployed at multiple locations within Shinnecock and Peconic Bays during C. polykrikoides bloom events on Long Island (NY, USA). In 2014, responses among two size-classes of each shellfish species (C. virginica, M. mercenaria, and A. irradians) were examined. First-year shellfish (all species) were obtained from the East Hampton Town Shellfish Hatchery (EHTSH; Montauk, NY, USA). Second-year clams and oysters were obtained from EHTSH and second-year size-class bay scallops were collected from eastern Shinnecock Bay (40.8647° N, 72.4913° W). In 2015, juvenile scallops (first-year only) were obtained from the Cornell University Cooperative Extension (Southold, NY). Prior to deployments, all shellfish were maintained in flow-through sea tables (~23 °C) for ~2 weeks at the Stony Brook—Southampton Marine Science Center which circulates water from eastern Shinnecock Bay.

Shellfish Deployments—2014

Shellfish were deployed August 13, prior to blooms, at surface and bottom positions (~2 m) in Old Fort Pond (OFP; within eastern Shinnecock Bay; 40.8688° N, 72.4468° W) and East Creek (EC; northern shore of Peconic Bay; 40.9439° N, 72.5702° W; Fig. 1), two locations prone to annual blooms of C. polykrikoides. In addition, shellfish were deployed at the northern shore of Shinnecock Bay (NS; control site within eastern Shinnecock Bay; 40.8827° N, 72.4893° W), a site typically void (personal observation, unpublished) of C. polykrikoides. Prior to deployments, each individual shellfish was measured. Larger size-class individuals were labeled with glue-on shellfish tags (Hall Print Fish Tags®). One hundred first-year clams (3.83 ± 0.18 mm; mean shell height ± S.D.) and oysters (4.86 ± 0.19 mm; mean shell height ± S.D.) and 50 first-year scallops (5.71 ± 0.11 mm; mean shell height ± S.D.) were added to surface and bottom shellfish rafts (3 rafts species−1 depth−1; e.g., 6 rafts location−1 species−1; 18 rafts site−1). For 2014 deployments, first-year shellfish were maintained within smaller mesh (1 mm opening) bags placed into larger (5 mm; see below) grow-out rafts. Each mesh bag was replaced weekly. Shellfish rafts (Go Deep International®) were approximately 1 × 0.5 × 0.05 m (l × w × h) with 5 mm openings. As shellfish grew, individuals were transferred into 15 mm mesh size rafts (same dimensions as above) to increase water flow around shellfish and limit fouling. For second-year size-class individuals, 50 clams (13 ± 3.02 mm; mean shell height ± S.D.) and oysters (32 ± 4.25 mm; mean shell height), and 30 scallops (53 ± 3.60 mm; mean shell height ± S.D.) were within each raft (same dimensions and replication as above) at each site. Mean bottom depth at all sites was 2 m; all surface rafts were deployed just below the water surface using surface floats, whereas bottom bags were weighted and held ~10 cm above sediments. Care was taken to separate cohorts of shellfish within each raft using a permeable baffle. Bivalves were examined weekly at each location. During weekly monitoring, water samples were collected at surface and depth using horizontal Van Dorn bottles. Samples for C. polykrikoides enumeration were preserved in a 1% Lugol’s iodine solution and quantified microscopically using a Sedgewick-Rafter counting chamber. Chlorophyll a (5 μm) was analyzed fluorometrically according to Parsons et al. (1984). Other water quality measurements were made at surface and bottom (temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and salinity) using a multi-parameter handheld sonde (YSI®). In addition to weekly quantification of water quality parameters, temperature and DO loggers (Onset HOBO®) were placed in surface and bottom rafts at each locale to provide continuous data during the entire experiment at each site. Experiments ended when C. polykrikoides cells were no longer present at any of the locations (e.g., 26 Sept 2014). Final shell heights of each shellfish were determined upon the termination of the deployment and used to calculate final growth rates (mm day−1) for each species and size-class.

Shellfish Deployments—2015

An additional series of experiments was conducted during the summer of 2015 with first-year scallops (~15 mm) only. Scallops, obtained from the Cornell University Cooperative Extension Marine Program (Southold, NY), were deployed within OFP and at Tiana Beach (TB; 40.8289° N, 72.5305° W; Fig. 1) within western Shinnecock Bay, a site historically void of C. polykrikoides. Shellfish were deployed in grow-out rafts (15 mm mesh size; n = 3 rafts site−1 position−1; n = 100 scallops raft−1; see above for description) at surface and at depth prior to the occurrence of C. polykrikoides blooms (e.g., 2 Sept 2015). Shellfish were monitored for survival and temperature and DO monitored as described for 2014. Experiments lasted ~1 week due to a mass mortality event associated with a C. polykrikoides bloom and thus growth was not quantified.

Assessment of Diel Vertical Migration

Multiple diurnal water collections were conducted over 72 h within OFP during the peak of the 2014 bloom (9–12 Sept 2014) to identify spatial and temporal patterns of cell densities among surface and bottom positions. At 2- and 3-h intervals, water samples were collected from the surface and bottom using a horizontal Van Dorn water sampler. Samples were preserved in Lugol’s iodine and cell densities determined using a compound light microscope.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R® (www.r-project.org,Version 3.4.4) software. To compare differences in the growth and survival of shellfish, a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each age-class with ‘species,’ ‘site,’ and ‘position’ included as the main, fixed effects. Surface and bottom bags, within each site, were maintained independent from one another and thus it was assumed that effects at one position did not carry-over to concurrently deployed shellfish at the same position or to individuals at other positions. Maximum cell densities between sites and positions were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. All data was verified to conform to a normal distribution with equal variance using Kolmogorov-Smirnov Goodness-of-Fit and Levene’s (http://cran.r-project/package=car) tests respectively. When significant differences were detected, a Tukey’s honest significant difference (Tukey HSD) test was performed to identify the source of variance and to adjust p values for multiple comparisons. Differences in levels of environmental variables (e.g., mean temperature, dissolved oxygen, and chlorophyll a) between sites and among surface and bottom positions within each site during deployments were analyzed using a linear mixed effect model (LME; https://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme) with ‘site’ and ‘position’ included as fixed effects in addition to a random effect of ‘time’ to account for non-independence (i.e., repeated measures) of measurements over time. Assumptions of a normal distribution were confirmed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s test. Unequal variances of environmental parameters between sites and among position within sites were observed and as such, site- and position-specific variances were included in model parameters. Pairwise comparisons of environmental conditions within and between shellfish deployment sites were analyzed using least-square means (http://cran.r-project.org/packag=lsmean) and p values adjusted as per Tukey’s method. All results were deemed significant at α ≤ 0.05.

Results

Progression of Blooms During 2014 and 2015

Blooms of C. polykrikoides were present at both OFP and EC during the last week of August (2014) and persisted for ~3 weeks (Figs. 2 and 3). Maximum cell densities observed during the second week of September (11–19 Sept 2014) varied significantly by site (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA) and by position within each site (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA). Peak surface densities at each location were significantly (p < 0.001; Tukey HSD) greater than those observed within the bottom waters and, regardless of position, densities were the greatest at OFP, followed by EC, and then NS; of which, all were significantly different (all p < 0.001; Tukey HSD; Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Maximum densities were 34,950 ± 2404 and 2215 ± 98 cells mL−1 (mean ± S.D.) at the surface of OFP and EC, respectively. During the same period, densities within bottom positions at these locations were 4810 ± 240 and 275 ± 9 cells mL−1 respectively. Only low densities (18 ± 6 and 44 ± 6 cells mL−1; maximum surface and bottom densities respectively) of C. polykrikoides were observed at NS, making it an ideal control locale in 2014 (Fig. 4).

During 2015, C. polykrikoides was present in OFP throughout September (2–24 Sept 2014) and densities were found to differ between OFP and TB (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA) and by position within each site (p < 0.01; two-way ANOVA). Two distinct peaks in cell density were observed in OFP (Fig. 5, inset) with a first maximum occurring on September 10th peaking at 13,350 ± 438 cells mL−1 and a second maximum (7800 ± 59 cells mL−1) occurring on the 14th. In a manner similar to 2014, cell densities within bottom positions (212 ± 6 cells mL−1; maximum density) of OFP were significantly lower (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA) than those observed at the surface (Fig. 5, inset). Densities at TB (surface and bottom positions; data not shown) never exceeded 200 cells mL−1 and were significantly (p < 0.001; Tukey HSD) lower than levels (both surface and bottom) observed at OFP.

Shellfish Survival—Summer 2014

For first-year shellfish, significant (p < 0.01; three-way ANOVA; see Suppl. Table 1 for all pairwise comparisons) interactive effects between ‘species,’ ‘site,’ and ‘position’ were detected whereby survival of first-year scallops was significantly lower among surface positions of OFP only (Figs. 2 and 6a–c). Mortality of first-year scallops within surface positions of OFP was 69 ± 38% (mean ± S.D.), significantly (p < 0.01; Tukey HSD) enhanced relative to those cultured at the bottom (e.g., 17 ± 14%) and to any (p < 0.05; Tukey HSD) first-year shellfish cultured at any other site or position (Fig. 6c). No other differences in the survival of first-year shellfish were detected at any other site or position (Figs. 3, 4, and 6a–c). Similarly, for second-year shellfish, significant (p < 0.001; three-way ANOVA) interactive effects between ‘species,’ ‘site,’ and ‘position’ were detected with, again, scallops exhibiting significantly reduced survival within the surface waters of OFP only (Figs. 2 and 6d–f; see Suppl. Table 2 for all pairwise comparisons). The survival of second-year scallops within the surface of OFP was 5.6 ± 5% and significantly (all p < 0.01; Tukey HSD) reduced relative to the survival of all other second-year shellfish at any other site or position (Figs. 2 and 6d).

Shellfish Survival—Summer 2015

For the 2015 experiment, surface mortality was observed again (Fig. 5). When the C. polykrikoides bloom emerged in OFP, significant (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA; Fig. 5) scallop mortality followed at surface positions only, with 100% of scallops perishing. In contrast, scallops deployed at depth exhibited only 3% mortality. There was no effect of position or site on the survival of scallops deployed at TB where final survival was 97 and 93% at surface and bottom positions, respectively (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA; Fig. 5). Growth rates for 2015 deployments were not quantified since mortality was 100% in surface positions after 1 week.

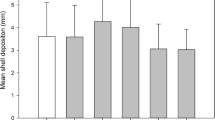

Shellfish Growth—First-Year—Summer 2014

Significant (all p < 0.001; three-way ANOVA) differences in growth rates between species were detected whereby first-year clams, regardless of site and/or position, grew slower than scallops and oysters (all p < 0.001; Tukey HSD; Fig. 7a–c). Additionally, significant (p < 0.001; three-way ANOVA) interactive effects between species, site, and position were observed (see Suppl. Table 3 for all pairwise comparisons). For first-year oysters, growth was the most rapid (0.56 mm day−1) at the surface of NS and significantly (all p < 0.01; Tukey HSD) greater than growth observed among first-year oysters deployed at either (surface or bottom) bloom-exposed site (Fig. 7b). The growth of firs-year oysters was slowest at EC and significantly reduced relative to oysters at either position within NS and surface positions of OFP (all p < 0.001; Tukey HSD), but similar (p > 0.05; Tukey HSD) to rates observed among bottom positions of OFP (Fig. 7b). The growth of first-year bay scallops, regardless of position, was significantly reduced at both locations where moderate to high densities of C. polykrikoides was observed, OFP (~35,000 cells mL−1) and EC (NS ~2500 cells mL−1), relative to the control site (both positions; all p < 0.01; Tukey HSD; Fig. 7c).

Shellfish Growth—Second-Year—Summer 2014

For second-year shellfish, again, species-specific differences (p < 0.001; three-way ANOVA; see Suppl. Table 4 for all pairwise comparisons) were observed with hard clams and bay scallops, regardless of position and site, growing slower than oysters (Fig. 7d–f). Significant interactive effects between site and position (p < 0.01; three-way ANOVA) were observed whereby hard clams grown among bottom positions of NS grew significantly (p = 0.0342; Tukey HSD), albeit slightly (e.g., 0.053 mm day−1), slower than those cultivated among bottom positions of OFP (Fig. 7d). For second-year oysters, growth rates among the surface of OFP were significantly (all p < 0.01; Tukey HSD) reduced relative to those cultivated at the surface of NS and among bottom positions of OFP, NS, and EC (Fig. 7e). Similarly, oysters among surface positions of EC grew slower relative to oysters among bottom positions of OFP and NS (Fig. 7e). There were no differences observed between the surviving scallops among any other sites or position within any site (Fig. 7f); however, survival of bay scallops was low (both age-classes, see “Shellfish Survival 2014—Summer 2014” section) at OFP; hence mean growth rates for this site were based upon the final lengths of the few surviving individuals within each raft.

Environmental Conditions During Bloom Events

Significant differences among environmental conditions were detected during 2014 shellfish deployments, but not during 2015. In 2014, temperatures during shellfish deployments (2014) were found to vary between site (p < 0.05; LME) and within each site (p < 0.05; LME; Table 1; Fig. 8). Surface temperatures at all sites were slightly, but significantly (all p < 0.05; Tukey HSD), warmer than at the bottom and among bottom positions, OFP was significantly (p < 0.05; Tukey HSD) warmer than NS and EC (Fig. 8a–c). There were no significant (p > 0.05; Tukey HSD) differences among surface temperatures at any deployment site. Levels of DO (Table 1) varied significantly (all p < 0.05; LME) within and between sites during deployments (Fig. 8). Within each site, DO levels at the bottom were significantly (all p < 0.05; Tukey HSD) lower than at the surface, and among surface-deployed shellfish, DO levels were significantly (both p < 0.05; Tukey HSD) lower at OFP and EC compared to NS. Similarly, DO levels among bottom positions were significantly (p < 0.05; Tukey HSD) lower at OFP and EC relative to NS, but were not different (p > 0.05; Tukey HSD) from one another. Chlorophyll a concentrations were found to vary by site (all p < 0.05; LME) whereby surface and bottom concentrations were significantly lower at NS relative to EC. No detectable (all p > 0.05; Tukey HSD) differences in chlorophyll a were observed between surface and bottom positions at any site (Table 1). During the 2015 shellfish deployments, no differences among environmental parameters (p > 0.05; LME) were observed (Fig. 9).

Diel Vertical Migration—2014

Surface waters of OFP had consistently higher concentrations of C. polykrikoides compared to bottom samples (Fig. 10 and Table 1). During a 72-h period, cell densities within surface positions increased throughout the day while decreasing slightly at night. Peak cell densities (24,950 ± 2404 cells mL−1) occurred at 22:30 (EST) on 11 Sept 2014 coinciding with a high tide (see Fig. 10) and decreased as the tide ebbed. Peak concentrations in bottom positions were significantly lower (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) at only ~4810 ± 240 cells mL−1. Cell concentrations at bottom positions generally mirrored densities at the surface, but were, on average, ~10-fold lower during peak bloom activity.

Discussion

Blooms of C. polykrikoides have long been known to be lethal to marine life, primarily cultured fish (Kim et al. 1999, 2000; Kudela and Gobler 2012). Results of this study demonstrate that blooms of C. polykrikoides, in addition to laboratory-based settings (Gobler et al. 2008; Tang and Gobler 2009a, 2009b), are lethal to shellfish in natural settings, posing a threat to multiple species and age-classes of bivalve molluscs. Differences in temperature were found to vary within and between deployment locations, but did not correspond directly with reduced survival or growth of shellfish. Effects were species-specific resulting in significantly reduced survival of bay scallops as well as the reduced growth of first-year scallops and oysters at bloom-prone sites. Scallop mortality, where present, was restricted to surface positions corresponding with maximum C. polykrikoides cell densities (Figs. 2a, b, 5, and 6e, f). Among commercially and ecologically significant North Atlantic bivalve shellfish, bay scallops appear to be at greater risk than oysters which appear more sensitive to blooms than clams and shellfish cultured at surface locations appear more vulnerable than those deployed at depth during C. polykrikoides blooms.

Implications for Shellfish Aquaculture

Aquaculture is a rapidly growing industry (FAO 2008, 2016b). Greater than half of the global seafood production now originates from cultured sources (FAO 2016b, a), supporting a growing demand for seafood that is an important source of protein and nutrition in many coastal communities (Mos et al. 2004; Hibbeln et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2010). Shellfish aquaculture in particular is growing in popularity due to its associated environmental benefits and its recognition as a ‘sustainable’ practice (Shumway et al. 2003; Burkholder and Shumway 2011). Results from this study, as well as others (see Ho and Zubkoff 1979; Gobler et al. 2008; Mulholland et al. 2009; Tang and Gobler 2009a, 2009b; Li et al. 2012), suggest that C. polykrikoides blooms represent a threat to shellfish aquaculture and that the impacts are species-specific.

Beyond mortality, oysters and scallops displayed significant reductions in growth at sites where C. polykrikoides was present. Specifically, first-year oysters at surface positions displayed slower growth at bloom prone sites (OFP and EC) relative to the control location (NS), a finding consistent with prior studies of bivalves and C. polykrikoides in North America (Gobler et al. 2008; Li et al. 2012). Further reductions in first-year oysters were observed among bottom-deployed first-year oysters deployed at OFP and EC, possibly a result of low DO. Levels of DO at both OFP and EC were significantly lower than the control site (NS) with both sites exhibiting extended excursions below 5 mg L−1 (Fig. 9), levels that are known to slow the growth of shellfish (Vaquer-Sunyer and Duarte 2008; Levin et al. 2009; Gobler et al. 2014; Clark and Gobler 2016). Lower DO, however, at locations where elevated C. polykrikoides densities were observed may be linked, indirectly, to the presence of blooms (Bauman et al. 2010; Morse et al. 2011). For example, blooms occurring at the surface may limit light levels reaching the bottom and provide large quantities of organic matter, a scenario that would favor enhanced rates of microbial respiration that reduce DO levels and slow shellfish growth (Kim et al. 2010; Bauman et al. 2010; Morse et al. 2011). The concurrent effects of HAB and other environmental stressors have been poorly studied, but may yield interactions that inhibit the performance of shellfish. For example, Talmage and Gobler (2012) reported that bay scallop larvae concurrently exposed to the HAB-forming pelagophyte Aureococcus anophagefferens and low pH displayed synergistically low survival, i.e., mortality was greater than would have been predicted based upon individual exposures to each stressor. Hence, aquaculture locales where multiple additional stressors are present may be highly vulnerable to HAB.

Results presented here have implications regarding the species-specific management of commercially produced shellfish. Bay scallops and first-year oysters that are negatively affected by dense C. polykrikoides blooms may benefit from relocation to grow-out sites or facilities where blooms are less likely to occur or are less intense. Clams (both year-classes) and second-year oysters were resistant to C. polykrikoides and thus may withstand moderate bloom events at grow-out sites and culture facilities. At grow-out sites where relocation of shellfish is not feasible, shellfish deployed at depth may be exposed to lower densities of C. polykrikoides than shellfish deployed at the surface and thus would be less apt to suffer mortality due to blooms, but may experience slowed growth at locations prone to low levels of dissolved oxygen.

Recent investigations have demonstrated that increases in sea surface temperatures, since the early 1980s, have contributed to increased growth and abundance of several HAB in areas where aquaculture is prominent (i.e., northwest Atlantic; Gobler et al. 2017). Additionally, warming can stimulate C. polykrikoides growth (Jeong et al. 2004; Lee and Lee 2006; Griffith and Gobler 2016) contributing to an increase in bloom intensities. Recently, such warming along the northeastern US has expanded the realized niche of C. polykrikoides (Griffith et al., in prep) with blooms now occurring annually in several locations including Chesapeake Bay (multiple tributaries; Marshall et al. 2006; Mulholland et al. 2009), Long Island (NY; Gobler et al. 2008, 2012), Rhode Island (Narragansett Bay; Hargraves and Maranda 2002), and Massachusetts (Buzzards Bay and Cap Cod; Kudela and Gobler 2012; Rheuban et al. 2016). Where present, blooms have been attributed to marine animal die-offs (Gobler et al. 2008; Mulholland et al. 2009; Morse et al. 2011) and in terms of shellfish mortality, there are reports of widespread mortality among shellfish populations following blooms of Cochlodinium (Curtiss et al. 2008; Gobler et al. 2008). Hence, as climate changes continue to expand within the Northern Hemisphere, the subsequent risk posed by these blooms will increase.

Species-Specific Effects of Exposure

The extreme sensitivity of bay scallops to C. polykrikoides is consistent with prior studies involving environmental stressors and these bivalves. Bay scallops are generally more sensitive to elevated temperatures (Tettelbach and Rhodes 1981; Brun et al. 2008; Talmage and Gobler 2011), acidification (Talmage and Gobler 2009), low dissolved oxygen (Bricelj et al. 1987; Chun-de and Fu-sui 1995; Clark and Gobler 2016), and exposure to other harmful algal species (Leverone et al. 2006, 2007) than other bivalves. Bay scallops rely upon carbohydrate reserves within adductor muscle tissue during periods of reduced food supplies (Barber and Blake 1981, 1983) and have a lower capacity for energy storage than other bivalves (Epp et al. 1988) making them more sensitive to stressors as food quality diminishes. Within the northwest Atlantic, bay scallop fisheries have been greatly diminished in recent decades due to over harvesting (Barber and Davis 1997; Oreska et al. 2017), habitat loss (Bowen and Valiela 2001; Serveiss et al. 2004; Orth et al. 2006), and recurrent harmful algal blooms (Cosper et al. 1987; Summerson and Peterson 1990). While some bay scallop restoration efforts have exhibited some success (Tettelbach et al. 2013), the current results indicate the annual recurrence of C. polykrikoides blooms may make restoration of bay scallops in bloom-exposed areas along the northeast US a significant challenge.

While the impacts of C. polykrikoides on oysters in the current study (slowed growth) were less severe than those exhibited by bay scallops (mortality), previous investigations from both the field and laboratory have described lethal effects of C. polykrikoides for oysters. Gobler et al. (2008) observed increased mortality among juvenile oysters and scallops following prolonged (9-day) laboratory exposures to bloom water. Similarly, Li et al. (2012) noted decreases in feeding activity, slow/no growth, and reduced survival of juvenile oysters following a prolonged (> 1 month) bloom of C. polykrikoides at a bloom-exposed oyster nursery. Differences between the sensitivities of oysters reported here and elsewhere may be due to the duration of bloom exposure. In the current study, oysters were exposed to short-term (< 9 days) but intense blooms (>30,000 cells mL−1), whereas reports of oyster mortality reported elsewhere (Gobler et al. 2008; Li et al. 2012) followed a more prolonged exposure to bloom conditions (≥ 9 days). To date, no study, including the present one, has reported on the harmful effects of C. polykrikoides for juvenile hard clams. Collectively, results presented here and elsewhere suggest that oysters and scallops are more vulnerable to C. polykrikoides blooms than clams and that the bay scallops are at greater risk than oysters.

Diel Vertical Migration

Previous investigations with East Asian ribotypes of C. polykrikoides from the field have indicated this alga undergoes diel movement throughout the water column over a 24-h period with greater cell densities quantified at the surface during daylight hours and dense subsurface maximums (e.g., 5–15 m) occurring at night (Park et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2010). In the current study, vertical movement was observed, but surface cell densities were consistently higher than bottom cell densities where levels were often an order of magnitude or more lower than surface concentrations. Differences in the magnitude of diel movements between this current study and observations elsewhere may be due to strain-specific variability or differences in hydrographic conditions among the study sites. In shallow well-mixed bays, cells may be more likely to aggregate at the surface during the daytime and simply disperse during the night or migrate onto or in sediments. Sites for the current study were shallower (~2 m) than those included in prior investigations (Park et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2010), and were in semi-enclosed bays rather than open seas. Nutrient levels, among shallow, tidally mixed, embayments studied here are similar at surface and at depth (Suffolk County Department of Health Services, suffolkcountyny.gov, 1976–2016) which may diminish diel movement of phytoplankton (Doblin et al. 2006) as vertical movement may not offer nutritional advantages. In larger, deeper, embayments where stratification of the water column is more pronounced, complete vertical migration of C. polykrikoides cells may be more pronounced.

Environmental Factors Influencing Toxicity

Environmental factors that influence the lethality of C. polykrikoides have yet to be fully investigated. For example, the impacts of irradiance on toxicity are currently unknown. While some controversy regarding the toxic mechanism of this HAB remains, the majority of evidence suggests that the toxic effects are, at least in part, related to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS; Kim et al. 1999; Tang and Gobler 2009a; Griffith and Gobler 2016). Production of ROS, a by-product of photosynthetic processes (Yu 1994; Wise 1995), would likely be greater during periods of adequate irradiance (i.e., surface positions during the daytime) and minimized during periods of low light (i.e., night or at depth). In addition to light effects, the effects of carbon dioxide (pCO2) on the growth and toxicity of C. polykrikoides have yet to be studied. In many temperate, net-heterotrophic estuaries, microbial respiration in bottom waters at night can elevate pCO2 levels (Wallace et al. 2014; Baumann et al. 2015). Such conditions may down-regulate photosynthetic machinery within phytoplankton and reduce ROS production (Sobrino et al. 2014), a phenomenon that may also diminish the toxicity of C. polykrikoides. Finally, while warmer temperatures are known to render C. polykrikoides less toxic (Griffith and Gobler 2016), there were no significant differences among surface temperatures during this study.

Conclusion

Blooms of the dinoflagellate C. polykrikoides pose a significant and growing threat to native and commercially produced shellfish within temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. During field experiments with three commercially and ecologically significant bivalves, species-specific reductions in growth and survival were observed. While hard clams were resistant to blooms, first-year oysters and scallops that survived blooms displayed significant reductions in growth and among the species deployed, only first- and second-year bay scallops exhibited significant declines in survivorship during blooms. Lethal effects, where observed, coincided with maximum C. polykrikoides cell densities and were restricted to surface positions only. Findings suggest that current restoration efforts and aquaculture involving bay scallops are vulnerable to recurring C. polykrikoides blooms and that risks posed to aquaculture may be greatest among surface-deployed shellfish where cell densities are likely to be greatest.

References

Abeels, H.A., A.N. Loh, and A.K. Volety. 2012. Trophic transfer and habitat use of oyster Crassostrea virginica reefs in southwest Florida, identified by stable isotope analysis. Marine Ecology Progress Series 462: 125–142. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09824.

Anderson DM, Hoagland P, Kaoru Y, White AW (2000) Estimated annual economic impacts from harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the United States. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Norman OK National Severe Storms Lab.

Barber, B.J., and N.J. Blake. 1981. Energy storage and utilization in relation to gametogenesis in Argopecten irradians concentricus (say). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 52: 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(81)90031-9.

Barber, B.J., and N.J. Blake. 1983. Growth and reproduction of the bay scallop, Argopecten irradians (Lamarck) at its southern distributional limit. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 66: 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(83)90163-6.

Barber, B.J., and C.V. Davis. 1997. Aquaculture International 5: 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018388812866.

Bauman, A.G., J.A. Burt, D.A. Feary, et al. 2010. Tropical harmful algal blooms: an emerging threat to coral reef communities? Marine Pollution Bulletin 60: 2117–2122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.08.015.

Baumann, H., R.B. Wallace, T. Tagliaferri, and C.J. Gobler. 2015. Large natural pH, CO2 and O2 fluctuations in a temperate tidal salt marsh on diel, seasonal, and interannual time scales. Estuaries and Coasts 38: 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9800-y.

Bowen, J.L., and I. Valiela. 2001. The ecological effects of urbanization of coastal watersheds: historical increases in nitrogen loads and eutrophication of Waquoit Bay estuaries. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 58: 1489–1500. https://doi.org/10.1139/f01-094.

Bricelj, V.M., J. Epp, and R.E. Malouf. 1987. Intraspecific variation in reproductive and somatic growth cycles of bay scallops Argopecten-irradians. Marine Ecology Progress Series 36: 123–137. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps036123.

Brun, N.T., V.M. Bricelj, T.H. MacRae, and N.W. Ross. 2008. Heat shock protein responses in thermally stressed bay scallops, Argopecten irradians, and sea scallops, Placopecten magellanicus. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 358: 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2008.02.006.

Burkholder, J.M., and S.E. Shumway. 2011. Bivalve shellfish aquaculture and eutrophication. In Shellfish aquaculture and the environment, ed. S.E. Shumway, 155–215. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Chun-de, W., and Z. Fu-sui. 1995. Effects of environmental oxygen deficiency on embryos and larvae of bay scallop, Argopecten irradians irradians. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 13: 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02889472.

Clark, H.R., and C.J. Gobler. 2016. Diurnal fluctuations in CO2 and dissolved oxygen concentrations do not provide a refuge from hypoxia and acidification for early-life-stage bivalves. Marine Ecology Progress Series 558: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps11852.

Coen, L.D., R.D. Brumbaugh, D. Bushek, et al. 2007. Ecosystem services related to oyster restoration. Marine Ecology Progress Series 341: 303–307. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps341303.

Cosper, E.M., W.C. Dennison, E.J. Carpenter, et al. 1987. Recurrent and persistent brown tide blooms perturb coastal marine ecosystem. Estuaries 10: 284. https://doi.org/10.2307/1351885.

Curtiss, C.C., G.W. Langlois, L.B. Busse, et al. 2008. The emergence of Cochlodinium along the California coast (USA). Harmful Algae 7: 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2007.12.012.

Dame, R.F. 1996. Ecology fo marine bivalves: an ecosystem approach. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Doblin, M.A., P.A. Thompson, A.T. Revill, et al. 2006. Vertical migration of the toxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum under different concentrations of nutrients and humic substances in culture. Harmful Algae 5: 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2006.02.002.

Ekstrom, J.A., L. Suatoni, S.R. Cooley, et al. 2015. Vulnerability and adaptation of US shellfisheries to ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change 5: 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2508.

Epp, J., V.M. Bricelj, and R.E. Malouf. 1988. Seasonal partitioning and utilization of energy reserves in two age classes of the bay scallop Argopecten irradians irradians (Lamarck). Journal of experimental biology and ecology 121.

FAO. 2008. The state of the world fisheries and aquaculture. Rome 2009.

FAO. 2016a. FishStat plus—universal software for the fishery statistical time series. Fisheries and Aquaculture Department: Food and Agriculutra Organization of the United Nations.

FAO (2016b) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Contributing to food security and nutrition for all. Rome 200 pp.

Fraga, S., S.M. Gallager, and D.M. Anderson. 1989. Chain-forming dinoflagellates: an adaptation to red tides. In Red tides: biology, environmental science, and toxicology, ed. T. Okaichi, D.M. Anderson, and T. Nemoto, 281–284. Inc.: Evesier Science Publishing Co.

Glibert, P.M., J. Icarus Allen, Y. Artioli, et al. 2014. Vulnerability of coastal ecosystems to changes in harmful algal bloom distribution in response to climate change: projections based on model analysis. Global Change Biology 20: 3845–3858. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12662.

Gobler, C., D.L. Berry, O.R. Anderson, et al. 2008. Characterization, dynamics, and ecological impacts of harmful Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooms on eastern Long Island, NY, USA. Harmful Algae 7: 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2007.12.006.

Gobler, C.J., A. Burson, F. Koch, et al. 2012. The role of nitrogenous nutrients in the occurrence of harmful algal blooms caused by Cochlodinium polykrikoides in New York estuaries (USA). Harmful Algae 17: 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2012.03.001.

Gobler, C.J., E.L. DePasquale, A.W. Griffith, and H. Baumann. 2014. Hypoxia and acidification have additive and synergistic negative effects on the growth, survival, and metamorphosis of early life stage bivalves. PLoS One 9: e83648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083648.

Gobler, C.J., O.M. Doherty, T.K. Hattenrath-Lehman, et al. 2017. Ocean warming since 1982 has expanded the niche of toxic algal blooms in the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences In press.

Grabowski, J.H., and C.H. Peterson. 2007. Restoring oyster reefs to recover ecosystem services. In Ecosystem engineers: plants to protists, ed. K. Cuddington, J. Byers, W. Wilson, and A. Hastings, 281–298. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Grabowski, J.H., R.D. Brumbaugh, R.F. Conrad, et al. 2012. Economic valuation of ecosystem services provided by oyster reefs. Bioscience 62: 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.10.10.

Griffith, A.W., and C.J. Gobler. 2016. Temperature controls the toxicity of the icthyotoxic dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Marine Ecology Progress Series 545: 63–76.

Hallegraeff, G.M. 2010. Ocean climate change, phytoplankton community responses, and harmful algal blooms: a formidable predictive challenge. Journal of Phycology 46: 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00815.x.

Hargraves, P.E., and L. Maranda. 2002. Potentially toxic or harmful microalgae from the northeast coast. Northeastern Naturalist 9: 81–120.

Hégaret, H., G. Wikfors, S. Shumway, and G. Rodrick. 2009. Biotoxin contamination and shellfish safety. Shellfish safety and quality: 43–80.

Hibbeln, J.R., J.M. Davis, C. Steer, et al. 2007. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an observational cohort study. The Lancet 369: 578–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60277-3.

Ho M-S, Zubkoff PL (1979) The effects of a Cochlodinium heterolobatum [algae] bloom on the survival and calcium uptake by larvae of the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica [Virginia]. Developments in marine biology.

Iwataki, M., H. Kawami, K. Mizushima, et al. 2008. Phylogenetic relationships in the harmful dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides (Gymnodiniales, Dinophyceae) inferred from LSU rDNA sequences. Harmful Algae 7: 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2007.12.003.

Jeong, H.J., Y.D. Yoo, J.S. Kim, et al. 2004. Mixotrophy in the phototrophic harmful alga Cochlodinium polykrikoides (Dinophycean): prey species, the effects of prey concentration, and grazing impact. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 51: 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00292.x.

Jiang, X.D., Y.Z. Tang, D.J. Lonsdale, and C.J. Gobler. 2009. Deleterious consequences of a red tide dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides for the calanoid copepod Acartia tonsa. Marine Ecology Progress Series 390: 105–116. https://doi.org/10.3354/Meps08159.

Jiang, X., D.J. Lonsdale, and C.J. Gobler. 2010. Grazers and vitamins shape chain formation in a bloom-forming dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Oecologia 164: 455–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-010-1695-0.

Kim, H.G. 1997. Recent harmful algal blooms and mitigation strategies in Korea. Ocean and Polar Research 19: 185–192.

Kim, C.S., S.G. Lee, C.K. Lee, et al. 1999. Reactive oxygen species as causative agents in the ichthyotoxicity of the red tide dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Journal of Plankton Research 21: 2105–2115. https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/21.11.2105.

Kim, C.S., S.G. Lee, and H.G. Kim. 2000. Biochemical responses of fish exposed to a harmful dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 254: 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-0981(00)00263-x.

Kim, Y.S., C.S. Jeong, G.T. Seong, et al. 2010. Diurnal vertical migration of Cochlodinium polykrikoides during the red tide in Korean coastal sea waters. Journal of Environmental Biology 31: 687–693.

Kudela, R.M., and C.J. Gobler. 2012. Harmful dinoflagellate blooms caused by Cochlodinium sp.: global expansion and ecological strategies facilitating bloom formation. Harmful Algae 14: 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.015.

Kudela, R.M., J.P. Ryan, M.D. Blakely, et al. 2008. Linking the physiology and ecology of Cochlodinium to better understand harmful algal bloom events: a comparative approach. Harmful Algae 7: 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2007.12.016.

Landsberg, J.H. 2010. The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Reviews in Fisheries Science 10(2):113–390.

Lee, Y.S., and S.Y. Lee. 2006. Factors affecting outbreaks of Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooms in coastal areas of Korea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 52: 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.10.015.

Leverone, J.R., N.J. Blake, R.H. Pierce, and S.E. Shumway. 2006. Effects of the dinoflagellate Karenia brevis on larval development in three species of bivalve mollusc from Florida. Toxicon 48: 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.04.012.

Leverone, J.R., S.E. Shumway, and N.J. Blake. 2007. Comparative effects of the toxic dinoflagellate Karenia brevis on clearance rates in juveniles of four bivalve molluscs from Florida, USA. Toxicon 49: 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.11.003.

Levin, L.A., W. Ekau, A.J. Gooday, et al. 2009. Effects of natural and human-induced hypoxia on coastal benthos. Biogeosciences 6: 2063–2098. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-6-2063-2009.

Li, Y., S.L. Meseck, M.S. Dixon, et al. 2012. Temporal variability in phytoplankton removal by a commercial, suspended eastern oyster nursery and effects on local plankton dynamics. Journal of Shellfish Research 31: 1077–1089. https://doi.org/10.2983/035.031.0419.

Marshall, H.G., R.V. Lacouture, C. Buchanan, and J.M. Johnson. 2006. Phytoplankton assemblages associated with water quality and salinity regions in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 69: 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2006.03.019.

Morse, R.E., J. Shen, J.L. Blanco-Garcia, et al. 2011. Environmental and physical controls on the formation and transport of blooms of the dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides Margalef in the lower Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Estuaries and Coasts 34: 1006–1025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-011-9398-2.

Mos, L., J. Jack, D. Cullon, et al. 2004. The importance of marine foods to a near-urban first nation community in Coastal British Columbia, Canada: toward a risk-benefit assessment. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 67: 791–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390490428224a.

Mulholland, M.R., R.E. Morse, G.E. Boneillo, et al. 2009. Understanding causes and impacts of the dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium polykrikoides, blooms in the Chesapeake Bay. Estuaries and Coasts 32: 734–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-009-9169-5.

Neiland, A.E., S.A. Shaw, and D. Bailly. 1991. The social and economic impact of quaculture: a European review. In Aquaculture and the environment, ed. N. De Pauw and J. Joyce. Gent, Belgium: European Aquacluture Soceity Special Publication.

Newell, R.I. 2004. Ecosystem influences of natural and cultivated populations of suspension-feeding bivalve molluscs: a review. Journal of Shellfish Research 23: 51–62.

NMFS (2015) Fisheries of the United States 2014. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA current fishery statistics no. 2014. National Marine Fisheries Service.

Officer, C.B., T.J. Smayda, and R. Mann. 1982. Benthic filter feeding—a natural eutrophication control. Marine Ecology Progress Series 9: 203–210. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps009203.

Oreska, M.P.J., B. Truitt, R.J. Orth, and M.W. Luckenbach. 2017. The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) industry collapse in Virginia and its implications for the successful management of scallop-seagrass habitats. Marine Policy 75: 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.10.021.

Orth, R.J., T.J.B. Carruthers, W.C. Dennison, et al. 2006. A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. Bioscience 56: 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[987:Agcfse]2.0.Co;2.

Park, J.G., M.K. Jeong, J.A. Lee, et al. 2001. Diurnal vertical migration of a harmful dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium polykrikoides (Dinophyceae), during a red tide in coastal waters of Namhae Island, Korea. Phycologia 40: 292–297. https://doi.org/10.2216/i0031-8884-40-3-292.1.

Parsons, T.R., Y. Maita, and C. Lalli. 1984. A manual of chemical and biological methods for seawater analysis. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Rheuban, J.E., S. Williamson, J.E. Costa, et al. 2016. Spatial and temporal trends in summertime climate and water quality indicators in the coastal embayments of Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts. Biogeosciences 13: 253–265. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-253-2016.

Richlen, M.L., S.L. Morton, E.A. Jamali, et al. 2010. The catastrophic 2008–2009 red tide in the Arabian gulf region, with observations on the identification and phylogeny of the fish-killing dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Harmful Algae 9: 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2009.08.013.

Schütt, F. 1895. Die Peridineen der Plankton-Expedition. Leipzig: Lipsius & Tischer.

Serveiss, V.B., J.L. Bowen, D. Dow, and I. Valiela. 2004. Using ecological risk assessment to identify the major anthropogenic stressor in the Waquoit Bay watershed, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Environmental Management 33: 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0085-y.

Shumway, S.E. 1990. A review of the effects of algal blooms on shellfish and aquaculture. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 21: 65–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-7345.1990.tb00529.x.

Shumway, S.E., C. Davis, R. Downey, et al. 2003. Shellfish aquaculture–in praise of sustainable economies and environments. World Aquaculture 34: 8–10.

Smayda, T.J., and C.S. Reynolds. 2003. Strategies of marine dinoflagellate survival and some rules of assembly. Journal of Sea Research 49: 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1385-1101(02)00219-8.

Smith, M.D., C.A. Roheim, L.B. Crowder, et al. 2010. Economics. Sustainability and global seafood. Science 327: 784–786. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185345.

Sobrino, C., M. Segovia, P.J. Neale, et al. 2014. Effect of CO2, nutrients and light on coastal plankton. IV. Physiological responses. Aquatic Biology 22: 77–93. https://doi.org/10.3354/ab00590.

Summerson, H.C., and C.H. Peterson. 1990. Recruitment failure of the bay scallop, Argopecten irradians concentricus, during the first red tide, Ptychodiscus brevis, outbreak recorded in North Carolina. Estuaries 13: 322. https://doi.org/10.2307/1351923.

Talmage, S.C., and C.J. Gobler. 2009. The effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations on the metamorphosis, size, and survival of larval hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria), bay scallops (Argopecten irradians), and eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica). Limnology and Oceanography 54: 2072–2080. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2009.54.6.2072.

Talmage, S.C., and C.J. Gobler. 2011. Effects of elevated temperature and carbon dioxide on the growth and survival of larvae and juveniles of three species of Northwest Atlantic bivalves. PLoS One 6: e26941. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026941.

Talmage, S.C., and C.J. Gobler. 2012. Effects of CO2 and the harmful alga Aureococcus anophagefferens on growth and survival of oyster and scallop larvae. Marine Ecology Progress Series 464: 121–134. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09867.

Tang, Y.Z., and C.J. Gobler. 2009a. Characterization of the toxicity of Cochlodinium polykrikoides isolates from northeast US estuaries to finfish and shellfish. Harmful Algae 8: 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2008.10.001.

Tang, Y.Z., and C.J. Gobler. 2009b. Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooms and clonal isolates from the Northwest Atlantic coast cause rapid mortality in larvae of multiple bivalve species. Marine Biology 156: 2601–2611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-009-1285-z.

Tettelbach, S.T., and E.W. Rhodes. 1981. Combined effects of temperature and salinity on embryos and larvae of the northern bay scallop Argopecten irradians irradians. Marine Biology 63: 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00395994.

Tettelbach, S.T., B.J. Peterson, J.M. Carroll, et al. 2013. Priming the larval pump: resurgence of bay scallop recruitment following initiation of intensive restoration efforts. Marine Ecology Progress Series 478: 153–172. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps10111.

Tolley, S.G., and A.K. Volety. 2005. The role of oysters in habitat use of oyster reefs by resident fishes and decapod crustaceans. Journal of Shellfish Research 24: 1007–1012. https://doi.org/10.2983/0730-8000(2005)24[1007:trooih]2.0.co;2.

Vaquer-Sunyer, R., and C.M. Duarte. 2008. Thresholds of hypoxia for marine biodiversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 15452–15457. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0803833105.

Wall, C.C., B.J. Peterson, and C.J. Gobler. 2011. The growth of estuarine resources (Zostera marina, Mercenaria mercenaria, Crassostrea virginica, Argopecten irradians, Cyprinodon variegatus) in response to nutrient loading and enhanced suspension feeding by adult shellfish. Estuaries and Coasts 34: 1262–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-011-9377-7.

Wallace, R.B., H. Baumann, J.S. Grear, et al. 2014. Coastal ocean acidification: The other eutrophication problem. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 148: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2014.05.027.

Wise, R.R. 1995. Chilling-enhanced photooxidation: the production, action and study of reactive oxygen species produced during chilling in the light. Photosynthesis Research 45: 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00032579.

Yu, B.P. 1994. Cellular defenses against damage from reactive oxygen species. Physiological Reviews 74: 139–162.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Deana Erdner

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1

(PDF 26 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

(PDF 26 kb)

Supplementary Table 3

(PDF 27 kb)

Supplementary Table 4

(PDF 27 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffith, A.W., Shumway, S.E. & Gobler, C.J. Differential Mortality of North Atlantic Bivalve Molluscs During Harmful Algal Blooms Caused by the Dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium (a.k.a. Margalefidinium) polykrikoides. Estuaries and Coasts 42, 190–203 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-018-0445-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-018-0445-0