Abstract

Introduction

Smoking may reduce the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but its impact on bronchodilator efficacy is unclear. This analysis of the EMAX trial explored efficacy and safety of dual- versus mono-bronchodilator therapy in current or former smokers with COPD.

Methods

The 24-week EMAX trial evaluated lung function, symptoms, health status, exacerbations, clinically important deterioration, and safety with umeclidinium/vilanterol, umeclidinium, and salmeterol in symptomatic patients at low exacerbation risk who were not receiving ICS. Current and former smoker subgroups were defined by smoking status at screening.

Results

The analysis included 1203 (50%) current smokers and 1221 (50%) former smokers. Both subgroups demonstrated greater improvements from baseline in trough FEV1 at week 24 (primary endpoint) with umeclidinium/vilanterol versus umeclidinium (least squares [LS] mean difference, mL [95% CI]; current: 84 [50, 117]; former: 49 [18, 80]) and salmeterol (current: 165 [132, 198]; former: 117 [86, 148]) and larger reductions in rescue medication inhalations/day over 24 weeks versus umeclidinium (LS mean difference [95% CI]; current: − 0.42 [− 0.63, − 0.20]; former: − 0.25 − 0.44, − 0.05]) and salmeterol (current: − 0.28 [− 0.49, − 0.06]; former: − 0.29 [− 0.49, − 0.09]). Umeclidinium/vilanterol increased the odds (odds ratio [95% CI]) of clinically significant improvement at week 24 in Transition Dyspnea Index versus umeclidinium (current: 1.54 [1.16, 2.06]; former: 1.32 [0.99, 1.75]) and salmeterol (current: 1.37 (1.03, 1.82]; former: 1.60 [1.20, 2.13]) and Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms–COPD versus umeclidinium (current: 1.54 [1.13, 2.09]; former: 1.50 [1.11, 2.04]) and salmeterol (current: 1.53 [1.13, 2.08]; former: 1.53 [1.12, 2.08]). All treatments were well tolerated in both subgroups.

Conclusions

In current and former smokers, umeclidinium/vilanterol provided greater improvements in lung function and symptoms versus umeclidinium and salmeterol, supporting consideration of dual-bronchodilator therapy in symptomatic patients with COPD regardless of their smoking status.

Plain Language Summary

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often require daily medication to control their COPD. Many patients with COPD are smokers, and smoking is one of the most common causes of COPD. This means that it is important to find out whether COPD medications are effective in both smokers and nonsmokers. We analyzed data from a clinical trial (EMAX) that investigated the use of a combination of two bronchodilators, which are inhaled medications that help to open the airways. We compared umeclidinium/vilanterol, a dual-bronchodilator combination, with a single bronchodilator (either umeclidinium or salmeterol) over 6 months. We found that both current and former smokers who were treated with umeclidinium/vilanterol had larger improvements in lung function than those receiving umeclidinium or salmeterol. Current or former smokers who were treated with umeclidinium/vilanterol used their reliever inhaler less than those treated with umeclidinium or salmeterol. Patients treated with umeclidinium/vilanterol were generally less likely to experience disease worsening compared with umeclidinium or salmeterol if they were former smokers, or compared with salmeterol if they were current smokers. Our findings suggest that umeclidinium/vilanterol may be more effective than a single bronchodilator for daily treatment of patients with COPD who are current or former smokers. Physicians should consider prescribing a combination of two bronchodilators to patients who have symptoms, whether or not they currently smoke, as well as encouraging smoking cessation for all patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Clinical trials have demonstrated significantly greater improvements in lung function, symptoms, and health-related quality of life with long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting β2-agonist (LAMA/LABA) dual therapies compared with LAMA or LABA monotherapies; however, few studies have explored the efficacy of these treatments in current and former smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). |

This prespecified analysis of the randomized, double-blind EMAX trial explored the efficacy and safety of umeclidinium/vilanterol (UMEC/VI) compared with UMEC or salmeterol (SAL) in current and former smokers. |

What was learned during this study? |

Improvements in lung function and reductions in rescue medication use were seen in both current and former smokers receiving UMEC/VI compared with those treated with UMEC or SAL. |

These findings suggest that dual-bronchodilator therapy may be an appropriate treatment option for patients with symptomatic COPD irrespective of their smoking status. |

Introduction

In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), poorly controlled symptoms are associated with worse health-related quality of life, increased risk of COPD exacerbations, and a poor disease prognosis [1,2,3]. Smoking is one of the most prominent risk factors for COPD, and the prevalence of COPD is higher in current and former smokers than in nonsmokers [4]. Among patients with COPD, current smokers have a greater rate of decline in lung function than former smokers [5, 6], and smoking also has an impact on COPD symptoms and health status [7, 8]. Smoking cessation can reduce long-term mortality risk [9] and is therefore an important element of COPD management, along with pharmacological maintenance therapy for many patients [4, 10]. However, it remains unclear how the efficacy of maintenance treatment for COPD is affected by patients’ smoking behavior.

Long-acting bronchodilators are recommended for most patients requiring maintenance therapy for COPD [4, 10]. Many patients remain symptomatic during treatment with one long-acting bronchodilator [11], suggesting a need for additional therapy. Analyses of clinical trial data have demonstrated greater improvements in lung function, symptoms, and health status with long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting β2-agonist (LAMA/LABA) dual therapy compared with LAMA or LABA monotherapy [12,13,14,15]. The efficacy of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment in patients with COPD appears to be impaired by smoking, but the effect of smoking on the efficacy of bronchodilators is less well understood. A post hoc analysis of the 12-month SUMMIT trial showed blunted improvement in lung function with ICS and ICS/LABA versus placebo, as well as a smaller reduction in exacerbation rates with ICS/LABA versus placebo, among current smokers compared with former smokers [16]. A systematic review of seven clinical trials (including SUMMIT) also found that current smokers gained less benefit from ICS-containing therapy than former smokers [17]. In contrast, the SUMMIT analysis showed similar benefits of the LABA vilanterol versus placebo between current and former smokers [16]. The LAMAs tiotropium and glycopyrronium have also demonstrated improvements in lung function and health-related quality of life compared with placebo in both current and former smokers [18, 19]. Similarly, in a post hoc analysis of the FLIGHT studies, improvements in lung function, symptoms, and health status observed with the LAMA/LABA indacaterol/glycopyrronium compared with its constituent monotherapies and placebo after 12 weeks of treatment were similar between current and former smokers [20]. Taken together this evidence suggests that, in contrast with ICS-containing therapy, the efficacy of bronchodilator therapy is less affected by patients’ smoking status.

The aim of this prespecified analysis of the EMAX trial was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of umeclidinium/vilanterol in current and former smokers with COPD. We hypothesized that both current smokers and former smokers would achieve greater improvements in lung function, symptoms, and health status with umeclidinium/vilanterol (UMEC/VI) compared with UMEC and salmeterol (SAL). In addition, we explored whether the magnitude of improvements from baseline with UMEC/VI, UMEC, or SAL was similar in current and former smokers.

Methods

Study Design and Ethical Approval

EMAX was a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy, three-arm parallel-group trial, in which patients were randomized 1:1:1 to 24 weeks of once-daily UMEC/VI (62.5/25 µg) via the ELLIPTA inhaler, once-daily UMEC (62.5 µg) via ELLIPTA, or twice-daily SAL (50 µg) via the DISKUS inhaler. The trial began in June 2017 and was completed in June 2018. Full details of the trial methodology have been published previously [21].

The EMAX trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, and received appropriate ethical approval (Supplementary Table S1). Patients provided written informed consent at the pre-screening or screening visit.

Patients

Eligible patients were at least 40 years of age and were current/former smokers with a COPD diagnosis, pre- and post-albuterol forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio < 0.7, post-albuterol FEV1 of at least 30% to at most 80% predicted (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] grade 2/3), COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score ≥ 10, and at most one moderate and no severe exacerbations in the previous year. Prior to screening and during the 4-week run-in period, treatment with at most one maintenance bronchodilator monotherapy (LAMA or LABA) was permitted. Patients had no ICS or ICS/LABA treatment for at least 6 weeks prior to run-in, and no LAMA/LABA combination therapy for at least 2 weeks prior to run-in. After the run-in period, patients received study treatment for 24 weeks.

In this analysis, patients were categorized into two subgroups based on their smoking status at screening (current smoker or former smoker). The EMAX trial did not include any patients who had never smoked.

Endpoints

Outcomes evaluated in the EMAX trial included spirometry, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), exacerbations, clinically important deteriorations (CID), and safety. For this analysis, spirometry outcomes were change from baseline in trough FEV1, FVC, and inspiratory capacity (IC). PROs were self-administered computerized Transition Dyspnea Index (SAC-TDI) focal score, Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms–COPD (E-RS) total score, rescue medication use (inhalations/day and the proportion of rescue-free days), global assessment of disease severity (GADS), St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score, and CAT total score. Response rates were also evaluated for SAC-TDI score (at least a 1-unit improvement from baseline) [22], E-RS score (at least a 2-point reduction from baseline) [23], SGRQ score (at least a 4-point reduction from baseline) [24], and CAT score (at least a 2-point reduction from baseline) [25]. Risk of a first CID was assessed in individual patients according to three composite definitions: 1. a first moderate or severe exacerbation, and/or a trough FEV1 decrease from baseline of at least 100 mL, and/or a deterioration in SGRQ (at least 4 units from baseline); 2. as per the first definition with a CAT deterioration (at least 2 units from baseline) replacing SGRQ deterioration; 3. a first moderate or severe exacerbation, and/or a SGRQ deterioration, and/or a CAT deterioration, and/or a SAC-TDI deterioration (at least a 1-unit decrease from baseline). Safety outcomes included the incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs).

Statistical Analysis

The EMAX trial was powered to detect differences in trough FEV1 and SAC-TDI at week 24 in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. The trial was not powered to detect differences between treatments in the smaller smoking status subgroups, so no formal statistical comparison was performed between subgroups. Accordingly, treatment differences with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported without reference to statistical significance between subgroups; however, P values are shown in the figures and tables.

Full details of the statistical analyses have been reported previously [21]. Mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analyses were performed for change from baseline in spirometry outcomes and PROs, and least squares (LS) mean and LS mean change from baseline are reported with estimated treatment differences and 95% CIs. Generalized linear mixed model analyses were used to evaluate response rates, and corresponding odds ratios (OR) are reported with 95% CIs. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to generate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs for time to first CID.

Results

Study Population

The EMAX ITT population included 2425 patients, of whom 1203 (50%) were current smokers (UMEC/VI: 394; UMEC: 396; SAL: 413) and 1221 (50%) were former smokers (UMEC/VI: 418; UMEC: 407; SAL: 396).

Table 1 shows baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of current and former smokers. On average, current smokers were slightly younger than former smokers, and a higher percentage were female. A greater proportion of current smokers than former smokers received no maintenance therapy in the 30 days prior to screening. Current smokers had a greater symptom burden as shown by higher baseline E-RS, CAT, and SGRQ scores and rescue medication use at baseline. A slightly smaller proportion of current smokers than former smokers experienced a moderate exacerbation in the prior year. Within each subgroup, baseline characteristics were well balanced between treatment groups (Supplementary Table 2).

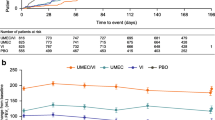

Lung Function Outcomes

Across all treatments and both subgroups, only UMEC/VI in current smokers provided mean improvements in trough FEV1 that consistently exceeded the minimum clinically important difference of 100 mL across all time points (Fig. 1). At week 24, mean (95% CI) change from baseline in trough FEV1 was higher with UMEC/VI versus UMEC by 84 (50, 117) mL in current smokers and 49 (18, 80) mL in former smokers; the corresponding treatment differences for UMEC/VI versus SAL were 165 (132, 198) mL in current smokers and 117 (86, 148) mL in former smokers (Table 2). Mean changes from baseline in trough FVC and trough IC at week 24 and all earlier time points were also numerically greater with UMEC/VI than UMEC and SAL in current and former smokers (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S1).

Symptom Severity and Health Status Outcomes

In both current and former smokers, larger mean SAC-TDI focal score and improvements from baseline in E-RS total score were observed with UMEC/VI compared with UMEC or SAL at all time points (Table 2; Figs. 2, 3). There were also greater odds of a clinically significant improvement for both outcomes at week 24 with UMEC/VI compared with UMEC or SAL (percentage of responders; SAC-TDI: UMEC/VI, 49–51% vs UMEC and SAL, 39–42%; E-RS: UMEC/VI, 35–37% vs UMEC and SAL, 26–29%; Fig. 4). Patients receiving UMEC/VI demonstrated larger reductions in mean rescue medication inhalations/day over 24 weeks versus UMEC and SAL in both smoking subgroups (Table 2; Figs. 5, 6). Improvements in the percentage of rescue-free days across all time points were seen with UMEC/VI compared with UMEC and SAL in current smokers, but this effect was less clear in former smokers (Table 2; Figs. 5, 6).

A SAC-TDI focal score and B change from baseline in E-RS total score across all time points in current smokers. CI confidence interval, E-RS Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms–COPD, LS least squares, MCID minimum clinically important difference, SAC-TDI self-administered computerized Transition Dyspnea Index, SAL salmeterol, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium, VI vilanterol

A SAC-TDI focal score and B change from baseline in E-RS total score across all time points in former smokers. CI confidence interval, E-RS Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms–COPD, LS least squares, MCID minimum clinically important difference, SAC-TDI self-administered computerized Transition Dyspnea Index, SAL salmeterol, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium, VI vilanterol

Proportion of responders for symptoms and health status outcomes in A current smokers and B former smokers. CAT COPD Assessment Test, CI confidence interval, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, E-RS Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms–COPD, SAC-TDI self-administered computerized Transition Dyspnea Index, SAL salmeterol, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium, VI vilanterol

Change from baseline in mean SGRQ and CAT scores across all time points were not consistently greater with UMEC/VI versus UMEC and SAL in current or former smokers (Supplementary Fig. S2). The odds of a clinically significant improvement in SGRQ score were numerically greater with UMEC/VI versus UMEC and SAL in both current smokers (percentage of responders; UMEC/VI: 45% vs 34–42%) and former smokers (percentage of responders: 45% vs 38–40%) (Fig. 4). Similarly, CAT responder rates were numerically higher for UMEC/VI versus UMEC and SAL in current smokers (percentage of responders; UMEC/VI: 52% vs 46–48%) and former smokers (percentage of responders; 58% vs 48–55%; Fig. 4).

Exacerbations and Disease Stability Outcomes

The risk of a first moderate/severe exacerbation (HR [95% CI]) with UMEC/VI versus UMEC was similar in current smokers (0.98 [0.65, 1.49]), but reduced in former smokers (0.70 [0.50, 1.00]). Compared with SAL, UMEC/VI significantly reduced the risk of a first moderate/severe exacerbation in both current (0.68 [0.46, 0.99]) and former smokers (0.60 [0.43, 0.85]).

In current smokers, the risk of a first CID was reduced with UMEC/VI versus UMEC for one of three CID definitions, and versus SAL for all three definitions, while in former smokers, UMEC/VI reduced CID risk versus UMEC and SAL for all three definitions (Fig. 7).

Risk of a first CID in A current smokers and B former smokers. an/N number of patients with an event/number of patients with at least one post-baseline assessment (not including exacerbations) for at least one of the individual components or patients who had an exacerbation; bmoderate/severe exacerbation. CAT COPD Assessment Test, CI confidence interval, CID clinically important deterioration, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FEV1 trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s, HR hazard ratio, SAC-TDI self-administered computerized Transition Dyspnea Index, SAL salmeterol, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium, VI vilanterol

Effect of Smoking Status on Mean Improvements from Baseline

For four clinical outcomes of interest (trough FEV1, SAC-TDI, rescue medication inhalations/day, and SGRQ score), LS mean improvements in all treatment arms at week 24 were numerically larger in current smokers than former smokers, with the exception of SGRQ score in patients receiving SAL (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, S2A). For trough FEV1 in patients receiving UMEC/VI (Fig. 1), and for rescue medication inhalations/day in all treatment groups (Figs. 5a, 6a), there was no overlap in the 95% CIs between the subgroups, suggesting that current smokers may show greater improvements in lung function and larger reductions in rescue medication use than former smokers; for all other treatment groups and outcomes there was overlap in the 95% CIs between subgroups.

Safety

A similar percentage of patients in each treatment arm reported on-treatment AEs and SAEs, and these percentages were similar in current and former smokers (Table 3). There were no drug-related SAEs in current or former smokers. There were four fatal SAEs in each subgroup, none of which were considered treatment-related.

Discussion

This prespecified analysis of the EMAX trial suggests that both current and former smokers experienced larger improvements in lung function and reductions in daily rescue medication use with UMEC/VI versus UMEC or SAL. The study was not powered to investigate subgroups and care should be taken when interpreting the results. However, consistent directional improvements with UMEC/VI versus monotherapy were also observed for other symptoms outcomes (SAC-TDI and E-RS). Furthermore, patients receiving UMEC/VI also had greater odds of improvements exceeding the MCID for SAC-TDI and E-RS total score in current and former smokers compared with UMEC and SAL. A generally reduced risk of moderate/severe exacerbations was observed with UMEC/VI compared with monotherapy in both subgroups, which is consistent with the findings in the ITT population [21]. However, longer studies are typically needed to fully investigate treatment effect on exacerbations and the EMAX trial included a relatively small proportion of patients with a history of moderate exacerbations in the past year (16% in the ITT population). Former smokers also demonstrated a reduced risk of a CID with UMEC/VI versus both monotherapies, while current smokers showed a consistent reduction in risk versus SAL. All treatments demonstrated a similar AE profile in both subgroups. Overall, these findings are consistent with a treatment benefit of dual bronchodilators compared with monotherapy in patients with COPD who are current or former smokers.

Current smokers demonstrated greater improvements from baseline in lung function with UMEC/VI and daily rescue medication use on all treatments compared with former smokers, with no overlap in the 95% CIs for the two subgroups. This difference in treatment outcomes may be related to baseline differences between the subgroups; current smokers had a more severe symptom burden than former smokers, as demonstrated by higher baseline E-RS, CAT, and SGRQ scores, although mean baseline FEV1 was higher in current smokers. The difference in baseline symptom severity may be related to the smaller proportion of current smokers receiving bronchodilator therapy during run-in compared with former smokers, since these undertreated patients may be expected to show greater improvements when initiating treatment at the start of the trial.

On the basis of time-to-first-event analyses, both current and former smokers generally demonstrated a reduced risk of exacerbations and disease worsening (CID) with UMEC/VI versus UMEC or SAL. This treatment effect was particularly prominent in former smokers, who had a reduced risk of exacerbations and CID across all definitions with UMEC/VI versus both monotherapies. In contrast, current smokers had consistently reduced risk with UMEC/VI versus SAL, but only showed a benefit for one of three CID definitions compared with UMEC, and risk of a first exacerbation was similar between the UMEC/VI and UMEC treatment arms in current smokers. However, the UMEC arm showed the highest rates of early discontinuation in the ITT population (UMEC/VI: 12%; UMEC: 19%; SAL: 16%) [21], which may have biased the analysis of exacerbations in favor of UMEC [26]. The small reduction in exacerbations and CID risk for two definitions with UMEC/VI versus UMEC in current smokers may therefore be an anomaly related to the excess early dropouts on the UMEC group, and to the low proportion of patients with an exacerbation in the prior year in the EMAX population. In support of this, treatment differences for the non-exacerbation components of the CID composite (FEV1, SGRQ, CAT, and SAC-TDI) were generally similar or larger in current smokers than in former smokers. Previous studies have also shown similar effects of LAMA monotherapy on lung function and symptoms outcomes in current and former smokers [18, 19, 27].

This analysis of EMAX provides longer-term evidence of similar efficacy and safety of LAMA/LABA therapy in current and former smokers, consistent with the findings of a post hoc analysis of the 12-week FLIGHT studies [20]. Taken together, the evidence suggests that dual-bronchodilator therapy is a suitable maintenance treatment option for both current and former smokers with COPD. Nonetheless, smoking cessation is an important aspect of the management of COPD, and should be encouraged for all patients who smoke [4]. An important aim of future studies will be to determine whether dual-bronchodilator therapy can help to minimize long-term risk and deterioration in lung function; this is particularly pertinent in former smokers, who have an elevated risk of mortality and a greater rate of lung function decline than nonsmokers [5, 6, 9].

A strength of this study is that EMAX selected an ICS-free population of patients with COPD, allowing a prospective assessment of the efficacy of dual and mono-bronchodilators independent of the potentially confounding effect of variable ICS use that has been noted in previous trials [12, 28]. However, a major limitation is that there were differences in patient characteristics between current and former smokers, which are consistent with a more severe COPD symptom burden and less frequent use of COPD maintenance therapy among current smokers. These baseline differences limit the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the effect of smoking status on long-acting bronchodilator efficacy, although our results do support greater efficacy of UMEC/VI compared with UMEC or SAL in both subgroups. In addition, only approximately 16% of the overall population had a history of exacerbations in the prior year, which together with the 24-week duration of the study may have limited the ability of the analysis to fully confirm reductions in exacerbation risk. Furthermore, the study was not powered to detect treatment differences in the smoking status subgroups.

Conclusion

In this analysis of the EMAX trial, dual-bronchodilator treatment with UMEC/VI provided improvements in lung function and reduced rescue medication use and was similarly well tolerated compared with UMEC and SAL monotherapy in both current and former smokers. Directional improvements with UMEC/VI versus monotherapy were observed in both subgroups for other symptoms outcomes (SAC-TDI and E-RS) and the risk of moderate/severe exacerbations. Current smokers showed greater overall benefits than former smokers with all three treatments. These findings suggest that dual-bronchodilator therapy is a suitable treatment option for symptomatic patients with COPD, regardless of their smoking status.

References

Vogelmeier CF, Roman-Rodriguez M, Singh D, Han MK, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Ferguson GT. Goals of COPD treatment: focus on symptoms and exacerbations. Respir Med. 2020;166:105938.

Miravitlles M, Ribera A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):67.

Jones PW, Watz H, Wouters EF, Cazzola M. COPD: the patient perspective. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11 Spec Iss:13–20.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2021.

Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Brook RD, et al. Fluticasone furoate, vilanterol, and lung function decline in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heightened cardiovascular risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(1):47–55.

Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, et al. Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(4):332–8.

Roche N, Small M, Broomfield S, Higgins V, Pollard R. Real world COPD: association of morning symptoms with clinical and patient reported outcomes. COPD. 2013;10(6):679–86.

Wytrychiewicz K, Pankowski D, Janowski K, Bargiel-Matusiewicz K, Dabrowski J, Fal AM. Smoking status, body mass index, health-related quality of life, and acceptance of life with illness in stable outpatients with COPD. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1526.

Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, et al. The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:233–9.

Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56–69.

Dransfield MT, Bailey W, Crater G, Emmett A, O’Dell DM, Yawn B. Disease severity and symptoms among patients receiving monotherapy for COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20(1):46–53.

Sion KYJ, Huisman EL, Punekar YS, Naya I, Ismaila AS. A network meta-analysis of long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) combinations in COPD. Pulm Ther. 2017;3(2):297–316.

Oba Y, Sarva ST, Dias S. Efficacy and safety of long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist combinations in COPD: a network meta-analysis. Thorax. 2016;71(1):15–25.

Rodrigo GJ, Price D, Anzueto A, et al. LABA/LAMA combinations versus LAMA monotherapy or LABA/ICS in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:907–22.

Mammen MJ, Pai V, Aaron SD, Nici L, Alhazzani W, Alexander PE. Dual LABA/LAMA therapy versus LABA or LAMA monotherapy for COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis in Support of the American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(9):1133–43.

Bhatt SP, Anderson JA, Brook RD, et al. Cigarette smoking and response to inhaled corticosteroids in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1):1701393.

Sonnex K, Alleemudder H, Knaggs R. Impact of smoking status on the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037509.

Tashkin DP, Celli B, Kesten S, Lystig T, Mehra S, Decramer M. Long-term efficacy of tiotropium in relation to smoking status in the UPLIFT trial. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(2):287–94.

Tashkin DP, Goodin T, Bowling A, et al. Effect of smoking status on lung function, patient-reported outcomes, and safety among COPD patients treated with glycopyrrolate inhalation powder: pooled analysis of GEM1 and GEM2 studies. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):135.

Tashkin DP, Goodin T, Bowling A, et al. Effect of smoking status on lung function, patient-reported outcomes, and safety among patients with COPD treated with indacaterol/glycopyrrolate: pooled analysis of the FLIGHT1 and FLIGHT2 studies. Respir Med. 2019;155:113–20.

Maltais F, Bjermer L, Kerwin EM, et al. Efficacy of umeclidinium/vilanterol versus umeclidinium and salmeterol monotherapies in symptomatic patients with COPD not receiving inhaled corticosteroids: the EMAX randomised trial. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):238.

Mahler DA, Witek TJ Jr. The MCID of the transition dyspnea index is a total score of one unit. COPD. 2005;2(1):99–103.

Leidy NK, Murray LT, Monz BU, et al. Measuring respiratory symptoms of COPD: performance of the EXACT-Respiratory Symptoms Tool (E-RS) in three clinical trials. Respir Res. 2014;15:124.

Jones PW. Interpreting thresholds for a clinically significant change in health status in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):398–404.

Kon SSC, Canavan JL, Jones SE, et al. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):195–203.

Eriksson G, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, et al. The effect of COPD severity and study duration on exacerbation outcome in randomized controlled trials. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1457–68.

Moita J, Barbara C, Cardoso J, et al. Tiotropium improves FEV1 in patients with COPD irrespective of smoking status. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21(1):146–51.

Naya I, Tombs L, Lipson DA, Boucot I, Compton C. Impact of prior and concurrent medication on exacerbation risk with long-acting bronchodilators in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post hoc analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):60.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK study 201749; NCT03034915). GSK-affiliated authors had a role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report and GSK funded the article processing charges and open access fee.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including preparation of the draft manuscript under the direction and guidance of the authors, collating and incorporating authors’ comments for each draft, assembling tables and figures, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Katie White, PhD, and Mark Condon, DPhil, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, part of Fishawack Health, and was funded by GSK.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Author Contributions

PWJ, LT, CC, and DAL were involved in the conception/design of the study and the analysis/interpretation of the data. LHB, FM, and EMK were involved in the acquisition and analysis/interpretation of the data. IHB and CFV were involved in the analysis/interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have approved the final manuscript.

Prior Presentation

An abstract reporting some of the data included in this manuscript was presented at the 2019 British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting, and was published in Thorax, Volume 74, Supplement 2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2019-BTSabstracts2019.107).

Disclosures

Leif H. Bjermer has received honoraria for giving a lecture or attending an advisory board for Airsonett, ALK-Abelló, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Meda, Novartis, and Teva. Isabelle H. Boucot, David A. Lipson, Chris Compton, and Paul W. Jones are employees of GSK and hold stock and shares in GSK. Claus F. Vogelmeier has received grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Grifols, Mundipharma, Novartis, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Competence Network Asthma and COPD (ASCONET), and has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Berlin Chemie/Menarini, Chiesi, CSL Behring, GSK, Grifols, MedUpdate, Novartis, and Teva. François Maltais has received research grants for participating in multicenter trials for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Sanofi, and Novartis, and has received unrestricted research grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Grifols, and Novartis. Lee Tombs is a contingent worker on assignment at GSK. Edward M. Kerwin has served on advisory boards, speaker panels or received travel reimbursement for Amphastar, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Connect Biopharma, GSK, Mylan, Novartis, Pearl, Sunovion, Teva, and Theravance, and has received consulting fees from Cipla and GSK. ELLIPTA and DISKUS are owned by/licensed to the GSK group of companies.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, and received appropriate ethical approval (Supplementary Table S1). All patients provided written informed consent at either the pre-screening or screening visit.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bjermer, L.H., Boucot, I.H., Vogelmeier, C.F. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Umeclidinium/Vilanterol in Current and Former Smokers with COPD: A Prespecified Analysis of The EMAX Trial. Adv Ther 38, 4815–4835 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01855-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01855-y