Abstract

Microstructural composition of the hardened cement pastes are analyzed using nanoindentation and 29Si MAS NMR after curing time periods of 7 and 28 days. Two curing conditions, room condition (20°C with 0.1 MPa pressure) and an elevated condition (80°C with 10 MPa pressure) are prepared to hydrate cement pastes [water to cement (w/c) ratio of 0.45]. The degree of hydration of the cement paste quantified using nanoindentation was compared with that from 29Si MAS NMR. From nanoindentation of the hardened cement pastes, microstructural hydration products are characterized with respect to the corresponding modulus of elasticity. A hydration product, which has a relatively high modulus of elasticity over other known hydration products, was found in the hardened cement paste cured in elevated temperature and pressure. The effect of high pressure on the composition of the hydration product is discussed and it is hypothesized that the packing density of calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H) might increase when a cement paste is hydrated under high temperature and pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanotechnology was recognized as a promising emerging technology by many industrial sectors in the early 1990s and efforts have evolved toward utilizing nanoscale tools for development of new materials (Mattoussi et al. 1996; Lakshmi et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998; Bhushan 2007). It is currently being used in many fields including biomedical, electronic instruments, sensors and nano-modified materials. In the cement industry, early efforts in nanotechnology were directed to understanding the fundamental phenomena of cement hydration, pore structure and the cement degradation mechanism (Scrivener and Kirkpatrick 2008). Studies on nano-modified cements and cements with carbon nano-tubes, self-healing cement and other nano-based cementitious materials have been in progress for the last decade (Chaipanich et al. 2010). Moreover, nano-characterization of mechanical properties of materials using techniques such as nanoindentation and nano-scratch (Xu and Yao 2011) have increasingly become important tools for providing quantitative evaluation of nanomaterials (Ulm et al. 2007). Extensive investigations using nanoindentation technique have been performed in the last decade on many materials (Zhang et al. 2005). Nanoscale investigations of cement showed that nanoscale elastic modulus and hardness values are consistent with values obtained at the microscale (Velez et al. 2001) confirming the possible correlation across scales. Nanoindentation of cement paste has been recently reported by many researchers (Acker 2001; Constantinides et al. 2003; Mondal et al. 2007; Sorelli et al. 2008) and was strongly correlated to microstructure of hydrated cement paste (Zhu et al. 2007).

In reference to cement composition, a short description of cement clinker and hydrated cement components is provided with their classical notations in Table 1. Calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H) is known as the major hydration product making up to 67% of the hydrated Portland cement paste (Diamond 1976) and is therefore responsible for most of the strength and fracture resistance of hydrated cement. Moreover, most of the time-dependent mechanical properties of hydrated cement are believed to be controlled by C-S-H (Larbi 1993; Jennings and Tennis 1994). C-S-H morphology is believed to include at least two characteristic types of pores: nano pores, which lie between C-S-H mineral layers (less than 1 nm) and gel pores, which consist of the basic C-S-H gel (5 nm). The mechanical properties of C-S-H are strongly correlated to its porosity. The packing density, which is the complementary of porosity, is typically used to interpret the relationship between C-S-H morphology and its mechanical properties (Constantinides and Ulm 2007). Nanoindentation experiments of cement pastes have shown that outer and inner product C-S-H can be categorized as low density (LD) and high density (HD) C-S-H (Jennings 2000; Constantinides and Ulm 2007; Ulm et al. 2009). While many researchers reported nanoindentation of cement paste, there are very limited experiments on nanoindentation of C-S-H in the literature (DeJonga and Ulm 2007).

In this study, an investigation was conducted with the objective of understanding the significance of elevated temperature and pressure curing conditions on the hydration of Portland cement. Type II Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) pastes with water to cement ratio (w/c) 0.45 are hydrated for 7 and 28 days in two curing conditions: room condition of 20°C and 0.1 MPa pressure and an elevated condition of 80°C with 10 MPa pressure. The objective is to simulate curing conditions similar to those observed in deep oil wells. The choice of Type II cement was for its similarity to most oil well cements (OWC) used in the field. The rationale behind using curing periods of 7 and 28 days is to reach the maximum mechanical properties, specifically compressive strength, of cement and concrete at 7 and 28 days, respectively (American Concrete Institute 2011; Canadian Standards Association 2006). The microstructural characteristics of the hardened cement pastes are investigated by nanoindentation and 29Si MAS NMR. The results showed that the packing density of C-S-H might increase by applying high pressure on cement paste during its hydration.

Methods

Nanoindentation

Surface probing using depth-sensing indentation (hardness) tests has been used as non-destructive tests for metals for the last 100 years (Hertz 1881) and it has also been used for decades as a common in situ test for different types of structures. The precision of the nanoindentation apparatus is achieved by controlling and recording the time-dependent nanoscale displacement of the indenter tip as it changes with electrical capacitance. Loading is performed by sending an electrical signal to the coil causing the pendulum to rotate about its frictionless pivot, so that the diamond indenter penetrates the sample surface. The indenter tip displacement (penetration) is measured during loading and unloading with a parallel plate capacitor that has sub-nanometer resolution (Fischer-Cripps 2004). A schematic of the nanoindenter along with a representation of the loading and unloading curves are shown in Fig. 1.

The most common indenters include the three-sided pyramid (Berkovich) indenter, spherical indenter (Tweedie and Van Vliet 2006) and the flat-ended (punch) indenter (Riccardia and Montanari 2004). Two indenter tips can be used for analysis of cement paste nanoscale phases: the Berkovich indenter and the spherical indenter. The Berkovich indenter was successfully used for extracting the mechanical characteristics of individual microstructural phases in the cement paste (Ulm et al. 2007). On the other hand, the spherical indenter can be used to extract the stress–strain constitutive model of the cement nanocomposite (Kim et al. 2010). Using either tip, loading and unloading is used to extract the stiffness of the cement paste nanocomposite (spherical indenter) or its individual microstructural phases (Berkovich indenter). Previous experiments on hydrated cement paste showed that an indentation load in the range of 0.5–1.0 mN will produce an indentation depth in the range of 200–300 nm for a typical cement matrix (Kim et al. 2010).

Analysis of the nanoindentation data to extract elastic modulus can be performed following the Oliver and Pharr method (Oliver and Pharr 1992). This method recognizes the variation of the indent radius with depth. The total indentation depth ht is defined as the summation of the plastic depth hp and half of the elastic displacement he leading to

Hertz (1881) showed that the elastic displacement he is defined as

where a is the radius of the circle of contact at P = Pt and can be calculated as a function of the plastic depth hp and the indenter radius Ri as described by Eq. 3 while R is the relative radius of curvature of the residual impression

The relative radius of curvature R can be based on the radius of curvature of the indenter Ri and the radius of curvature of the residual impression Rr

The contact area A can be calculated from knowing the radius of the circle of contact a. Oliver and Pharr (1992) recognized that the unloading curve for a majority of materials indented followed a power fit rather than a linear relationship. Therefore, a power function can be fit to the top 60% of the unloading curve and the slope of indentation load–depth curve (dP/dh) will be calculated as the slope of a line tangent to the power fit relationship or the derivative of the power fit relationship. For the duration of each indentation, the applied load and the displacement of the specimen material are constantly measured, including unloading. The reduced modulus, Er is calculated as (Oliver and Pharr 1992; Fischer-Cripps 2004):

where β is a correction factor to account for the non-symmetrical shape of the indenter tip, which is equal to 1.034 for a 3-sided pyramidal (Berkovich) indenter. A is the contact area of the indenter, which is found by knowing the geometry of the indenter tip as a function of the depth, and the measured depth. For a Berkovich indenter tip, A is equal to Eq. 6 (Oliver and Pharr 1992; Fischer-Cripps 2004):

where hp is the depth of penetration and θ is the angle the edge of the indenter makes with the vertical. As the reduced modulus Er is for the elastic modulus to account for the affect of the indenter stiffness on measurements, the elastic modulus of the indented phases E is calculated from the relationship defined as

where E i and ν i are values corresponding to the indenter used, respectively, 1,141 and 0.07 GPa as reported by the indenter calibration. In this study, nanoindentation observations were analyzed to identify the microstructural phases of hardened cement paste and the corresponding elastic modulus.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

NMR has been proven over the years to be an efficient method to examine chemical bonds in different materials (Günther 1995). For solid-state NMR, the MAS method is used in order to avoid large peak broadenings caused by chemical shift anisotropy and dipolar interactions. This is conducted by spinning the sample at frequencies of 1–35 kHz around an axis oriented 54.7° to the magnetic field (Macomber 1998). NMR has helped in identifying the nanostructure of silicate composites. 29Si NMR has been used to examine the polymerization of a silicate tetrahedron in synthesized C-S-H (Lippmaa et al. 1980; Wieker et al. 1982). Silicate polymerization represents the number of bonds generated by the silicate tetrahedron. A silicate tetrahedron having the number of n shared oxygen atoms is expressed as Qn where n is the number oxygen atoms up to 4. The intensity of the silicate Q connections can be investigated using 29Si MAS NMR. Q0 is observed due to the remaining tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S) in hydrated cement while Q1 (end-chain group) and Q2 and Q3 (middle-chain group) in silicate are typically detected due to the layered structure of C-S-H. Q4 is the polymerization of the quartz and can be observed in silica-rich products such as fly ash and silica fume.

As ‘the next nearest neighbor’ of a silicate tetrahedron can affect chemical shift, the chemical shifts for silicate tetrahedral have variations (Wieker et al. 1982; Young 1988; Grutzeck et al. 1989). Using statistical deconvolution of NMR spectra, the different chemical shift peaks and the corresponding intensity, which represent silica polymerization type Q0–Q4 and its volume fraction, respectively, can be identified. A schematic representation of the typical chemical shift range is shown in Fig. 2. From the calculated intensity fractions of Qns, the average degree of C-S-H connectivity c s is calculated (Saoût et al. 2006b) as

Higher value of c s represents higher polymerization of C-S-H. From the extensive studies of the structure of C-S-H by 29Si MAS NMR, the polymerization of C-S-H depends on its compositional calcium-silicate (C/S) ratio (high polymerization for low C/S ratio) and the humidity in the interlayer water (high polymerization for low interlayer water) (Bell et al. 1990; Cong and Kirkpatrick 1996). Moreover, the degree of hydration h c of a hydrated cement paste is calculated (Saoût et al. 2006a) for the absence of Q4 by silica-rich products as

It is important to note that as the degree of hydration of a cement paste is generally estimated as the weighted average of the degree of reactivity of four major cement components of C3S, C2S, C3A and C4AF (Jennings and Tennis 1994), denoted as h ′ c here, the relationship between the degree of hydration h c and Q0 fraction in Eq. 9 neglects the contribution of the degree of reactivity of C3A and C4AF due to the absence of silicate in those components. However, as the weight fractions of C3A and C4AF in a cement are relatively small compared with other components including silicate such as C3S and C2S, h c in Eq. 9 will yield h ′ c estimated as the weighted average of the degree of reactivity of four major cement components. However, in this study, h c in Eq. 9 is converted to h ′ c in Eq. 18 in Appendix to estimate the volume fractions of hydration product of a cement paste using a model proposed by Jennings and Tennis (1994).

In this study, the 29Si NMR spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker ASX 300 spectrometer (7.05 T magnetic field) at 59.6 MHz. Spectra were recorded in 7 mm ZrO2 rotors spun at 4 kHz. Single-pulse experiments without 1H decoupling were carried out. Approximately 10,000 scans were performed on each sample. The 29Si chemical shifts are, respectively, referenced relative to tetramethylsilane Si(CH3)4 (TMS) at 0 ppm, using Si[(CH3)3]8Si8O20 (Q8M8) as a secondary reference (the major peak being at 11.6 ppm relatively to TMS).

Statistical deconvolution of spectra

The statistical deconvolution analysis technique (Meister 2009) was used to analyze nanoindentation and 29Si NMR MAS results. For the statistical deconvolution of the experimental results, the frequency density function of nanoindentation results and NMR spectra are assumed as a convolution function of n normal distributions such as

Here, λ is scale factor, which can be the number of nanoindentation tests for the frequency density function or the maximum intensity for NMR spectra. n can be considered as the number of different phases characterized by the property x on abscissa. f i , σ i and μ i represent the volume/surface fraction occupied by the ith phase, the standard deviation and the mean values of the ith phase, respectively. The convolution function in Eq. 10 is then determined by minimizing the standard error with the experimental observations or by maximizing the R2 value computed as

where x j and y(x j ) are the jth abscissa and ordinate values of the experimental results, respectively, and m is the number of the experimental results. For nanoindentation results, m is equal to the number of bins used to construct the frequency density function. To properly fit the convolution function to the experimental results, the R2 value needs to be maximized (close to 1.0). The mean, standard deviation, and volume fraction values of n phase are all unknowns and are thus determined by the deconvolution analysis.

Experiments

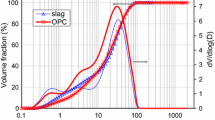

Materials

Water to cement ratio (w/c) of 0.45 was used for all cement paste specimens. For nanoindentation and 29Si MAS NMR of cement paste, two cylinders, ϕ 10 mm × 10 mm height, were prepared for each type mix. The specimens were molded in a tube for a day and then cured in the corresponding curing condition up to 7 or 28 days of age. The list of specimens and their curing conditions are presented in Table 2. Specimens were prepared for nanoindentation by first casting them in acrylic to fit them into the nanoindentation holder. The specimens were polished on a Buehler Ecomet 3 polisher with a Buehler Automet 2 power head. The steps used during polishing include: 10 min with a 125-µm diamond pad, 15 min with a 70-µm diamond pad, 15 min with a 30-µm diamond pad, 30 min with a 9-µm diamond lapping film pad, and 1 h with a 1-µm diamond lapping film pad. A total of 50 indentations were performed for each hydrated cement paste. Nanoindentation of cement paste was performed using a Berkovich tip loaded at 0.55 mN including 0.05 mN preloading. A dwell period of 60 s was used at maximum load to account for thermal drift and creep. The indentations were performed in five rows with ten indentations spaced at 200 μm on each row.

Curing conditions

Specimens were cured under tap water with a controlled temperature of 20°C and pressures 0.1 MPa (1 atm) for room curing condition, while a special setup for the elevated temperature 80°C and pressures 10 MPa (98.7 atm) curing conditions was prepared as shown in Fig. 3. 450 ml Parr® pressure vessel was used. Two-thirds of the vessel was filled with tap water and specimens were cured in the water under elevated temperature and pressure. Pressure was applied by injecting nitrogen gas from compressed nitrogen cylinder at 10 MPa and temperature was kept constant using the heater surrounding the pressure vessel controlled with thermocouple sensors.

Results and discussions

Degree of hydration and silicate polymerization by NMR spectra

The resulted 29Si MAS NMR spectra for the hardened cements hydrated under room condition and under the elevated condition for 7 and 28 days are compared in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. In both figures, it can be observed that the shape of chemical shift spectra for the hardened cements hydrated under the elevated conditions are skewed toward the right side, than that for the hardened cements hydrated under room conditions. Therefore, it is obvious that there exists a higher order of silicate polymerization of C-S-H in the hardened cements hydrated under elevated conditions than those under room conditions. The chemical shift spectra were deconvoluted and the effects of different curing conditions and time on the degree of C-S-H connectivity and the degree of hydration were examined. The peaks of −72, −78.5, −82.5, −85, −89 and −96 ppm for Q0, Q1, Q 2 L , Q2, Q 2 U and Q3 silicate connections are used for deconvolution analyses of NMR spectra, respectively. The standard deviations of 2 and 4 ppm for Eq. 10 are assigned to the normal distributions of Q0 to Q2 and Q3, respectively. While Q 2 L resonance at −82.5 ppm is caused from silicate connection Q2 with 1 Al connection (Richardson et al. 1993), Q 2 U resonance at −89 ppm is caused from Q2 connected by hydrogen bonding (Sato and Grutzek 1992). The integration results of the Qn intensities by the statistical deconvolution are presented in Table 3. It is noticeable that slight amount of Q3 level of polymerization, which can be observed in tobermorite or jennite, was found in the hardened cements hydrated under high temperature and pressure for 28 days. As expected from the shape of NMR spectra, the degrees of connectivity in Eq. 8 of the hardened cements hydrated under elevated curing conditions are 12 and 13% higher than those of the hardened cements hydrated under room conditions for 7 and 28 days of curing, respectively. However, there is almost no change in the degree of connectivity as a result of extending the curing time from 7 to 28 days. The difference in the degree of connectivity between 7 and 28 days of curing was limited to 1 and 2% for normal and elevated curing conditions, respectively, which can be regarded as insignificant.

For the effects of different curing conditions on the degree of hydration \(h^{\prime}_{c}\) (see Appendix), the elevated curing conditions increased the degree of hydration compared with the corresponding degree of hydration under room conditions, by 43% for 7 days curing and 31% for 28 days curing. While the degree of hydration of the hardened cements hydrated under room conditions increased from 57.8% at 7 days to 63.42% at 28 days, the degree of hydration of the hardened cements hydrated under elevated conditions increased from 82.5% at 7 days to 83.0% at 28 days. The results indicate that the elevated curing condition of cement pastes accelerates the hydration process significantly. It is therefore obvious that curing the specimens for 7 days under elevated curing conditions is sufficient to achieve the required degree of C-S-H connectivity. The difference between the degree of hydration between 7 and 28 days for both conditions is insignificant.

Nanoindentation

The distribution of the modulus of elasticity from the nanoindentation observations was deconvoluted. Similar microstructural phases to those identified from our nanoindentation experiments were reported by other researchers (Velez et al. 2001; Ulm et al. 2007; Mondal et al. 2007; Zhu et al. 2007). The statistical deconvolution analyses present an estimate of each phase volume fraction and its corresponding modulus of elasticity. The results of statistical deconvolution analysis are summarized in Table 4. A microstructural phase having the modulus of elasticity between 52 and 62 GPa appears in all four hydrated cement pastes. As there is no hydration product having that range of the modulus of elasticity in literature, we consider that phase as an unhydrated cement phase with capillary pores. This shall explain the low volume fraction of the ettringite phase, which is reported as the phase usually including the capillary pores (Ulm et al. 2007). The relatively low modulus of elasticity of unhydrated cement reported here compared with the range of 110–150 GPa in the literature (Velez et al. 2001; Mondal et al. 2007) is attributed to the inclusion of capillary pores. The relative volume fractions of major hydration product, LD-C-S-H, HD-C-S-H and calcium-hydroxide (CH), according to Q0 value from 29Si MAS NMR are quantified based on a model by Jennings and Tennis (1994), denoted ‘J&T model’ here (see Table 6 in Appendix). The calculated volume fractions of LD-C-S-H, HD-C-S-H and CH are compared with the volume fractions determined from nanoindentation in Fig. 7 for room curing conditions and Fig. 8 for the elevated curing conditions. As shown in Figs. 6a and 7a for 7 days of curing, the solid volume fractions of LD-C-S-H, HD-C-S-H and CH from nanoindentation reasonably agree with the estimated values from J&T model for both curing conditions. For 28 days of curing, a little difference can be observed for specimens under room curing conditions in Fig. 6b. However, a major difference can be observed for specimens cured under elevated curing conditions in Fig. 7b. This significant difference is attributed to finding a much less volume fraction of LD-C-S-H (12.0%) than that (46.1%) estimated from the J&T model. Moreover, the amount of LD-C-S-H is less than the amount of HD-C-S-H for 28 days curing under the elevated curing conditions in Fig. 7b and it is distinctive among nanoindentation observations in this study. This might be interpreted by the compaction of LD-C-S-H and HD-C-S-H due to high pressure as suggested below.

Comparison of relative fractions of C-S-H phases and CH in hydrated cement cured under room curing conditions from nanoindentation. a Results based on 7 days of curing compared with calculation based on J&T model using 57.8% degree of hydration and b results based on 28 days of curing compared with calculation based on J&T model using 63.4% degree of hydration (w/c 0.45, OPC Type II)

Comparison of relative fractions of C-S-H phases and CH in hydrated cement cured under elevated curing conditions from nanoindentation. a Results based on 7 days of curing compared with calculation based on J&T model using 82.5% degree of hydration and b results based on 28 days of curing compared with calculation based on J&T model using 83.0% degree of hydration (w/c 0.45, OPC Type II)

Hypothesis about a relatively stiff microstructure

The above experiments and analysis show that the volume fraction of LD-C-S-H at 28 days is much less than LD-C-S-H at 7 days cured under the elevated curing conditions as shown in Fig. 7a, b. Moreover, considering the necessity of monotonicity of the degree of hydration (i.e. cement hydration continues), the volume fraction of unhydrated cement for 28 days curing under the elevated conditions should be less than that for 7 days curing under the same condition. The above points make it difficult to accept the assumption that the phase of the material with the modulus of elasticity between 52 and 62 GPa is unhydrated cement with capillary pores as in Table 4. The above contradiction can be resolved by hypothesizing that the phase of material with the modulus of elasticity between 52 and 62 GPa is not only unhydrated cement with capillary pores under room curing conditions but also very highly compacted HD-C-S-H formed under high pressure curing conditions for 28 days. Moreover, the LD-C-S-H is also compacted under this pressure to make HD-C-S-H. This hypothesis is illustrated in Fig. 8 and compared with those calculated by the J&T model. This hypothesis makes our findings meet the predictions of the J&T model. The summation of LD-C-S-H volume (8.6%) and HD-C-S-H volume (37.1%) is similar with LD-C-S-H volume (46.1%) predicted by the J&T model. It is therefore possible to assume that part of the LD-C-S-H at 7 days of age was compacted to the HD-C-S-H. Furthermore, the new phase volume fraction of (28.6%) is very similar with HD-C-S-H volume (31.3%) predicted by the J&T model. The compaction of HD-C-S-H to very high density C-S-H (VHD-C-S-H) under high pressure is plausible. The above hypothesis is based on the assumption that LD-C-S-H and HD-C-S-H can be compacted under high pressure which is supported by the classical layered structure and gel-type structure of C-S-H suggested in the literature (Alizadeh and Beaudoin 2011; Jennings 2000).

Comparison of relative fractions of a new phase having the modulus of elasticity of 52–62 GPa, C-S-H phases and CH in hydrated cement cured under elevated curing conditions from nanoindentation based on 28 days of curing compared with J&T model using 83.0% degree of hydration (w/c 0.45, OPC Type II)

The layered structure of C-S-H is shown in Fig. 9a, the presence of silicate tetrahedral connectivity of Q3 under elevated curing conditions in Table 3 can support the appearance of a strong phase as Q3 has been observed in tobermorite-like C-S-H which is known to be crystalline and has relatively very high density (Alizadeh and Beaudoin 2011). Therefore, it is hypothesized that such high density C-S-H can be the result of combining high temperature favoring the formation of Q3 connectivity with the loss of interlayer water due to high pressure.

One can also explain the appearance of the strong phase based on the experiments by Constantinides and Ulm (2007). In their experiments, Constantinides and Ulm showed a nano-granular nature of C-S-H from the linear relationship of packing density and Young’s modulus for C-S-H. In granular mechanics, the mechanical properties of C-S-H particles are governed by the number of particle-to-particle contact. This contact increases with the increase of packing density. Therefore, if one considers the nano-granular nature of C-S-H, then microstructural phases such as LD-CSH (packing density 0.63) can be compacted to HD-C-S-H (packing density 0.76) or sintered to VHD-C-S-H. It is therefore possible that the compaction from LD- to HD- and HD- to VHD-C-S-H might occur under the elevated pressure conditions. Due to theoretical maximum packing density of 0.74 for a group of spheres, a density over 0.74 might be explained by sintering rather than compaction. We therefore hypothesize that the unknown phase is a very high density VHD-C-S-H that is encapsulated by ettringite-like (sulfate ion) shells. This hypothesis is described schematically in Fig. 9b using globule model proposed by Jennings (2000). The increase of ettringite-like phase (having the similar modulus of elasticity of ettringite between 4 and 6 GPa) and the compaction of C-S-H under the elevated curing conditions are illustrated in Fig. 9b. Further research investigation is necessary to confirm or negate this hypothesis. The formation of VHD-C-S-H might be examined by measuring the surface accessible to Helium gas to prove the removal of interlayer water due to high pressure or the surface accessible to nitrogen gas to prove the compaction of C-S-H globules by high pressure.

Conclusions

The microstructural compositions and the silicate polymerization of the cement pastes hydrated under two curing conditions, 20°C with 0.1 MPa pressure and 80°C with 10 MPa pressure, for 7 days were examined using nanoindentation and 29Si MAS NMR. It is evident from NMR and nanoindentation experiments that the hydration of the cement paste is faster under elevated curing conditions than under room curing conditions. It is also evident that the elevated curing conditions increase the polymerization of C-S-H considerably. A new phase of high modulus of elasticity that is stiffer than HD C-S-H is detected from nanoindentation. It is hypothesized that this new phase is a VHD-C-S-H. The high curing temperature favors the formation of Q3 connectivity and the high pressure might also play a role in the formation of VHD-C-S-H. Further experimental research is warranted to confirm or negate this observation.

References

Acker P (2001) Micromechanical analysis of creep and shrinkage mechanisms. Creep, shrinkage and durability mechanics of concrete and other quasi-brittle materials. In: Proceedings of ConCreep-6. MA, Elsevier

Alizadeh R, Beaudoin JJ (2011) Mechanical properties of calcium silicate hydrates. Mater Struct 44:13–28

Allen AA, Thomas JJ, Jennings HM (2007) Composition and density of nanoscale calcium-silicate-hydrate in cement. Nat Mater 6:311–316

American Concrete Institute (2011) Building code requirements for structural concrete, ACI 318-11, and commentary, USA

Bell GMM, Benstedm J, Glasser FP, Lachowski EE, Roberts DR, Taylor MJ (1990) Study of calcium silicate hydrates by solid state high resolution 29Si nuclear magnetic resonance. Adv Cem Res 3:23–37

Bhushan B (ed) (2007) Handbook of nanotechnology. Springer, Berlin

Canadian Standards Association (2006) Canadian Highway Bridge Design Code. CHBDC. CAN/CSA-S6-06, Canada

Chaipanich A, Nochaiya T, Wongkeo W, Torkittikul P (2010) Compressive strength and microstructure of carbon nanotubes-fly ash cement composites. Mater Sci Eng A 527(4–5):1063–1067

Cong X, Kirkpatrick RJ (1996) 29Si MAS NMR study of the structure of calcium silicate hydrate. Adv Cem Based Mater 3:144–156

Constantinides G, Ulm F-J (2007) The nanogranular nature of C-S-H. J Mech Phy Solids 55:64–90

Constantinides G, Ulm F-J, Van Vliet K (2003) On the use of nanoindentation for cementious materials. Mater Struct 36(April):191–196

DeJonga MJ, Ulm F-J (2007) The nanogranular behavior of C-S-H at elevated temperatures (up to 700°C). Cem Concr Res 37(1):1–12

Diamond S (1976) Cement paste microstructure—an overview at several levels. In: Conf. on hydraulic cement pastes: their structure and properties. Cement and Concrete Assoc. Tapton Hall, University of Sheffield

Fischer-Cripps AC (2004) Nanoindentation. Springer, New York

Grutzeck M, Benesi A, Fanning B (1989) Silicon-29 magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance study of calcium silicate hydrates. Am Ceram Soc 72:665–668

Günther H (1995) NMR spectroscopy: basic principles, concepts, and applications in chemistry. Wiley, Chichester

Hertz H (1881) On the contact of elastic solids. J Reine Angew Math 92:156–171

Jennings HM (2000) A model for the microstructure of calcium silicate hydrate in cement paste. Cem Concr Res 30:101–116

Jennings HM, Tennis PD (1994) Model for the developing microstructure in Portland cement pastes. J Am Ceram Soc 77(12):3161–3172

Kim JJ, Fan T, Reda Taha MM (2010) Homogenization model examining the effect of nanosilica on concrete strength and stiffness. Transp Res Rec 2141:28–35

Lakshmi BB, Patrissi CJ, Martin CR (1997) Sol-gel template synthesis of semiconductor oxide micro- and nanostructures. Chem Mater 9:2544–2550

Larbi JA (1993) Microstructure of the interfacial zone around aggregate particles in concrete. Heron 38(1):1–69

Lippmaa E, Mägi M, Samoson A, Engelhardt G, Grimmer AR (1980) Structural studies of silicates by solid-state high-resolution 29Si NMR. Am Chem Soc 102:4889–4893

Macomber RS (1998) A complete introduction to modern NMR spectroscopy. Wiley, New York

Mattoussi H, Cumming AW, Murray CB, Bawendi MG, Ober R (1996) Characterization of CdSe nanocrystallite dispersions by small angle X-ray scattering. J Chem Phys 105:9890–9896

Meister A (2009) Deconvolution problems in nonparametric statistics. Lecture Notes in Statistics. Springer, Berlin

Mondal P, Shah SP, Marks L (2007) A reliable technique to determine the local mechanical properties at the nanoscale for cementious materials. Cem Concr Res 37:1440–1444

Oliver W, Pharr G (1992) An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J Mater Res 7(6):1564–1583

Riccardia B, Montanari R (2004) Indentation of metals by a flat-ended cylindrical punch. Mater Sci Eng A 381(1–2):281–291

Richardson IG, Brough AR, Brydson R, Groves GW, Dobson C (1993) Location of aluminium in substituted calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gels as determined by 29Si and 27Al NMR and EELS. J Am Ceram Soc 76:2285–2288

Saoût GL, Le′colier E, Rivereau A, Le′colier E, Rivereau A, Zanni H (2006a) Chemical structure of cement aged at normal and elevated temperatures and pressures, Part I: class G oilwell cement. Cem Concr Res 36:71–78

Saoût GL, Le′colier E, Rivereau A, Zanni H (2006b) Chemical structure of cement aged at normal and elevated temperatures and pressures, Part II: low permeability class G oilwell cement. Cem Conc Res 36:428–433

Sato H, Grutzek M (1992) Effect of starting materials on the synthesis of Tobermorite. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc 245:235–240

Scrivener K, Kirkpatrick RJ (2008) Innovation in use and research on cementitious material. Cem Conc Res 38:128–136

Sorelli L, Constantinides G, Ulm F-J, Toutlemonde F (2008) The nano-mechanical signature of ultra high performance concrete by statistical nanoindentation techniques. Cem Conc Res 38:1447–1456

Taylor HFW (1987) A method for predicting alkali ion concentration in cement pore solutions. Adv Cem Res 1:5–17

Tennis PD, Jennings HM (2000) A model for two types of calcium silicate hydrate in the microstructure of Portland cement pastes. Cem Conc Res 30:855–863

Thomas JJ, Jennings HM (2006) A colloid interpretation of chemical aging of the C-S-H gel and its effects on the properties of cement paste. Cem Conc Res 36(1):30–38

Tweedie CA, Van Vliet KJ (2006) Contact creep compliance of viscoelastic materials via nanoindentation. J Mater Res 21(6):1576–1589

Ulm F-J, Vandamme M, Bobko C, Ortega JA, Tai K, Ortiz C (2007) Statistical indentation techniques for hydrated nanocomposites: concrete, bone, shale. J Am Ceram Soc 90(9):2677–2692

Ulm F-J, Vandamme M, Jennings HM, Vanzo J, Bentivegna M, Krakowiak KJ, Constantinides G, Bobko CP, Van Vliet KJ (2009) Does microstructure matter for statistical nanoindentation techniques? Cem Conc Comp 32:92–99

Velez K, Maximilien S, Damidot D, Fantozzi G, Sorrentino F (2001) Determination by nanoindentation of elastic modulus and hardness of pure constituents of Portland cement clinker. Cem Conc Res 31:555–561

Wang N, Zhang YF, Tang YH, Lee CS, Lee ST (1998) SiO2-enhanced synthesis of Si nanowires by laser ablation. Appl Phys Lett 73:3902–3904

Wieker W, Grimmer A-R, Winkler A, Mägi M, Tarmak M, Lippmaa E (1982) Solid-state high-resolution 29Si NMR spectroscopy of synthetic 14 Å, 11 and 9 Å tobermorites. Cem Concr Res 12:333–339

Xu J, Yao W (2011) Experimental study of the nano-scratch behavior of cement composite material. Key Eng Mater 492:47–54

Young JF (1988) Investigations of calcium silicate hydrate structure using silicon-29 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Am Ceram Soc 71(3):C118–C120

Zhang CY, Zhang YW, Zeng KY, Shen L (2005) Nanoindentation of polymers with a sharp indenter. J Mater Res 20(6):1597–1605

Zhu W, Hughes J, Bicanic N, Pearce C (2007) Nanoindentation mapping of mechanical properties of cement paste and natural rocks. Mat Charac 58(11–12):1189–1198

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) through the Science and Technology Unit at King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) for funding this work through Project #09-NAN754-04 as part of the National Science, Technology and Innovation Plan. Additional support to the first and last authors by National Science Foundation (NSF) award # 1131369 is greatly appreciated. Technical assistance in nanoindentation by Dr. Michael Sheyka and in MAS-NMR by Professor Karen Smith are greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Based on the fractions of C3S and C2S in cement, the total number of silicate tetrahedrons N Q is calculated as

where NA is Avogadro constant. MC3S and MC2S are the molecular weights of C3S and C2S, which are 0.228 kg/mol and 0.172 kg/mol (Jennings and Tennis 1994), respectively. p is the weight fraction of the subscribed components in cement. c is the initial weight of cement (in grams) in 1 g of cement paste calculated as

where, w/c is initial water to cement ratio of cement paste.

Considering the degree of reactivity of C3S and C2S, αC3S and αC2S, respectively, the numbers of silicate tetrahedrons having Q0 connection in the remaining C3S and C2S, \( N_{{Q^{0} ,{\text{C3S}}}} \) and \( N_{{Q^{0} ,{\text{C2S}}}} \), respectively, are also calculated as:

Q0 fraction determined from 29Si MAS NMR is then expressed as

To determine αC3S and αC2S for a given Q0 fraction using Eq. 16, Avrami-type equation after Taylor (1987) is used. The degree of reactivity of the cement components at a time t (days) is considered as follow as

The constants a, b and c used in the equations for the major cement components of C3S, C2S, C3A and C4AF are presented in Table 5 with the corresponding weight fractions of Type II OPC. By solving Eq. 16 regard to the time t, the degree of reactivity of the major cement components can be determined. The degree of hydration is then estimated as the weighted average of the degree of reactivity of the major cement components as

The relative volume fractions of major hydration product, LD-C-S-H, HD-C-S-H and CH, according to Q0 value from 29Si MAS NMR can be calculated and compared with those from nanoindentation experiments in Figs. 7 and 8. The total mass of C-S-H in 1 g of cement paste, mCSH, can be calculated as

where MCSH is the molecular weight of C-S-H and 0.188 kg/mol is used from the composition of C-S-H as (CaO)1.7(SiO2)(H2O)1.8 (Allen et al. 2007). From the equation for the ratio of the mass of LD-C-S-H to the total mass of C-S-H (Tennis and Jennings 2000),

The mass of LD-C-S-H and HD-C-S-H is determined as

Using the density of LD-C-S-H and HD-C-S-H as 1,440 and 1,750 kg/m3, respectively, when pores are empty (Thomas and Jennings 2006), the volumes of LD-C-S-H and HD-C-S-H in 1 g of cement paste, VLD and VHD, can be determined.The volume of CH in 1 g of cement paste is calculated (Jennings and Tennis 1994) as

Calculation procedures for Type II OPC cured under room condition for 7 days are presented in Table 6 for example.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.J., Rahman, M.K. & Reda Taha, M.M. Examining microstructural composition of hardened cement paste cured under high temperature and pressure using nanoindentation and 29Si MAS NMR. Appl Nanosci 2, 445–456 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-012-0058-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-012-0058-z