Abstract

Many studies have demonstrated that hepatic fibrosis is reversible. Regression of liver fibrosis is associated with resorption of fibrous scar and the disappearance of collagen-producing myofibroblasts. The fate of these myofibroblasts has been recently revealed: some myofibroblasts undergo senescence and apoptosis during reversal of fibrosis, whereas other myofibroblasts revert to a quiescent-like phenotype. Inactivation of myofibroblasts is a newly described phenomenon (Kisseleva et al. in Proc. Natl .Acad. Sci. USA 109:9448–9453, 2012) which now requires mechanistic investigation. Understanding the mechanism of inactivation of hepatic stellate cells on cessation of fibrogenic stimuli may identify new approaches to cause already existing activated hepatic stellate cells/myofibroblasts to revert to a quiescent-like state. This review summarizes the research on the inactivation of hepatic myofibroblasts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis is an outcome of many chronic liver diseases, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [2]. Hepatic fibrosis is characterized by extensive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, mostly type I collagen, forming a scar. Chronic liver injury damages hepatocytes. Injured or apoptotic hepatocytes secrete factors that facilitate activation and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the injured liver. Activated macrophages secrete IL-6 and transforming growth factor (TGF) β1, which in turn activate hepatic myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts are not present in the normal liver, but in response to injury they transdifferentiate from hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), upregulate collagen, and produce the fibrous scar. Myofibroblasts are characterized by expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and type I collagen, and in all clinical and experimental liver fibroses serve as a major source of the ECM. Thus, activation and proliferation of hepatic myofibroblasts is a key mechanism in the development of liver cirrhosis.

Myofibroblasts Are the Primary Target of Antifibrotic Therapy

Hepatic myofibroblasts are the major source of type I collagen in fibrotic liver. Therefore, elimination of myofibroblasts or their inactivation is a goal of therapy. Several sources of myofibroblasts have been identified [3–6]. It is believed that HSCs are the major source of fibrogenic myofibroblasts, and contribute more than 80 % of the collagen-producing cells [1••, 2, 7]. Under physiological conditions, HSCs reside in the space of Disse and exhibit a quiescent phenotype (quiescent HSCs, qHSCs). They express neural markers, such as glial fibrillar acidic protein (GFAP), synemin, synaptophysin, and nerve growth factor receptor p75, and store vitamin A in lipid droplets [3]. In response to injury, qHSCs decrease vitamin A storage and peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) expression, and activate into type I collagen and α-SMA expressing myofibroblasts [2]. Although the mechanism of HSC activation has been comprehensively studied, insights into the fate of HSCs during regression of liver fibrosis are new [8•]. In addition to HSCs, portal fibroblasts [9, 10] and bone-marrow-derived fibrocytes [11] can also contribute to hepatic myofibroblasts.

Reversal of Liver Fibrosis

Mechanism of Regression of Liver Fibrosis

Sequential liver biopsies from patients with liver fibrosis have demonstrated that removing the underlying etiological agent may reverse hepatic fibrosis in patients with secondary biliary fibrosis [12], hepatitis C [13], hepatitis B [14], nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [15], and autoimmune hepatitis [16]. Withdrawal of the etiological source of the chronic injury (e.g., hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus) [2] results in a decrease in the levels of proinflammatory and fibrogenic (including TGF-β1) cytokines, increased collagenase activity [2, 3], decreased ECM production, and the disappearance of activated myofibroblasts.

Studies of liver fibrosis in rodents have confirmed that established liver fibrosis can reverse on cessation of the action of the etiological agent. Reversal of liver fibrosis has been successfully studied in experimental models of CCl4 [17, 18], alcohol, and bile duct ligation [19] induced liver fibrosis [2]. Several events have been identified to be critical for regression of liver fibrosis. These include the disappearance of hepatic myofibroblasts/activated HSCs (aHSCs), recruitment of collagenese-secreting monocytes/macrophages, and the prevalence of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases over their natural inhibitors, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).

Conditions for Reversal of Liver Fibrosis

Bone-marrow-derived monocytes and liver-resident macrophages play an important role in reversal of liver fibrosis. Selective ablation of CD11b+ cells in mice (CD11b-DTR) during the phase of recovery from liver injury significantly attenuates fibrosis resolution, suggesting that macrophages mediate distinct functions at the onset of fibrosis and during recovery. Increased collagenase activity is a primary pathway of fibrosis resolution. At this stage, activated macrophages/Kupffer cells secrete matrix metalloproteinases, e.g., matrix metalloproteinase13, interstitial collagenase, and other enzymes responsible for matrix degradation [6, 20]. Moreover, increased activity of collagen-degrading enzymes during fibrosis resolution correlates with decreased amounts of TIMPs [21•, 22]. Activated myofibroblasts/aHSCs serve as a significant source of TIMPs, and the disappearance of myofibroblasts/HSCs during recovery is associated with reduced production of TIMPs.

An established mechanism for the elimination of activated myofibroblasts is due to senescence [23] and apoptosis of aHSCs [24]. Several mechanisms are implicated in the apoptosis of aHSCs: (1) activation of death-receptor-mediated pathways (Fas receptor or TNF receptor 1) and caspases 3 and 8; (2) upregulation of proapoptotic proteins (e.g., p53, Bax, and caspase 9); and (3) decrease of prosurvival genes (e.g., Bcl-2) [22]. A population of liver-associated natural killer cells and γδ T cells stimulatse apoptosis of aHSCs. Drugs that induce apoptosis in aHSCs (glyotoxin, sulfasalazine, IκB kinase inhibitors, and anti-TIMP antibodies) cause liver fibrosis to regress [2, 3].

Conditions for Irreversible Liver Fibrosis

Whether end-stage cirrhosis can revert to a normal liver architecture remains controversial [25, 26]. However, significant improvement in hepatic structure and function provides evidence of regression of liver fibrosis [21•, 27]. Perhaps ECM remodeling is limited in cirrhosis by the formation of nonreducible cross-linked collagen and an ECM rich in elastin fibers preventing its degradation. This pathophysiological state may lead to a “point of no return” for liver fibrosis [26, 27]. The characteristics of the myofibroblast environment play a critical role in myofibroblast survival. For example, stiffness of the ECM and increased contact between myofibroblasts and collagen scar promote survival of myofibroblasts and facilitate their activation [28]. In support of this notion, transgenic mice expressing an uncleavable form of type I collagen are more susceptible to liver fibrosis, and demonstrate a defect in spontaneous resolution of liver fibrosis on cessation of liver injury [29]. Similarly to what is found in these transgenic mice, prolongation of the duration of fibrogenic liver injury often results in the formation of persistent and uncleavable scars caused by irreversible cross-linking of collagen fibers. Furthermore, the presence of elastin fibers distinguishes “biochemically mature scars,” which are more likely to persist in recovering liver [18]. In addition, persistent scars are associated with the formation of areas of hypocellularity, suggesting that lack of biodegrading macrophages in these areas may contribute to poor desorption of fibrous scars [18].

The Role of Myofibroblasts in Reversal of Liver Fibrosis

Although aHSCs undergo senescence [23] and apoptosis [17] during the regression of liver fibrosis, the quantitative contribution of aHSC apoptosis to the disappearance of activated myofibroblasts remains unknown [27]. Further, the cellular population of HSCs is restored in mice recovering from fibrosis, and the source of these quiescent-like HSCs is unknown. Recent studies have suggested that in addition to apoptosis, aHSCs/activated myofibroblasts can be eliminated by their undergoing inactivation and reverting to a quiescent-like phenotype. We [1••], and subsequently others [30••], have used genetic marking to demonstrate an alternative pathway in which myofibroblasts revert to a quiescent-like phenotype in CCl4-induced liver injury and experimental alcoholic liver disease. The findings of these in vivo studies are in concordance with in vitro observations that suggested that cultured HSCs, at least in part, can revert to a quiescent-like phenotype. The quiescent phenotype of HSCs is associated with expression of lipogenic genes and storage of vitamin A in lipid droplets. Depletion of PPARγ is a key molecular event for HSC activation, and ectopic expression of this nuclear receptor results in the phenotypic reversal of aHSCs to quiescent cells in culture [31]. Treatment of aHSCs with an adipocyte differentiation cocktail or overexpression of SREBP-1c results in upregulation of adipogenic transcription factors and causes morphologic and biochemical reversal of aHSCs to quiescent-like cells [21•, 32, 33]. These in vitro and in vivo studies have provided new insights into the concept of reversibility of liver fibrosis, suggesting that the disappearance of activated myofibroblasts is attributed not only to their apoptosis but also to reversal of their phenotype to a quiescent-like phenotype.

Methods to Study Inactivation of HSCs

The Cre–lox system [34] provides a unique tool to monitor specific cellular populations and their progeny in mice [35]. This system is based on the ability of the small 38-kDa bacteriophage protein Cre recombinase to recognize and excise inverted 13 base pair loxP sequences and the flanking DNA [34, 36]. Genetic labeling of a specific cellular population is achieved by crossing mice expressing Cre under control of a cell-specific promoter with reporter Rosa26f/f-YFP mice ubiquitously expressing the yfp gene in which transcription is blocked by a floxed Stop cassette [36]. Genetic Cre–loxP recombination causes excision of the floxed–Stop–floxed sequence from genomic DNA, with activation of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) transcription in the resulting offspring. The cells of interest now irreversibly express YFP, so their phenotypic changes can be monitored in response to injury or stress [37].

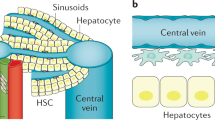

Using Cre–LoxP-based genetic labeling of myofibroblasts, we [1••] and others [30••] elucidated the fate of aHSCs/activated myofibroblasts during recovery from CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (Fig. 1a) [8•]. Genetic labeling of aHSC/myofibroblasts resulted from crossing mice expressing Cre under control of the type I collagen α1 [Col-α1(I)] enhancer/promoter [Col-α1(I)Cre mice] with reporter mice (Rosa26f/f-YFP mice). In the offspring [Col-α1(I)Cre-YFP mice], all type I collagen expressing cells expressed YFP. In uninjured mice, type I collagen is not expressed in the liver, and this correlates with minimal expression of YFP in livers of Col-α1(I)Cre-YFP mice. Following induction of liver injury in these mice, aHSCs and their progeny express collagen-driven YFP and are permanently labeled by YFP expression [1••]. Phenotypical changes of aHSCs and the mechanism of their inactivation can now be studied during regression of liver fibrosis (Fig. 1b) [8•]. Using two models of hepatotoxicity-induced liver fibrosis (CCl4 and intragastric alcohol feeding), we demonstrated that half of the myofibroblasts escape apoptosis during regression of liver fibrosis, downregulate fibrogenic genes (Col1a1, Col1a2, α-SMA, TIMP1, TGF-β receptor 1) and acquire a phenotype similar to, but distinct from, that of qHSCs [1••]. Similar results were obtained using inducible Cre-based systems, in which genetic labeling of aHSCs was achieved in Col-α1(I)–estrogen receptor–Cre and vimentin–estrogen receptor–Cre mice on tamoxifen administration.

Study design to determine the fate of activated hepatic stellate cells (aHSCs) during regression of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. a Cre–loxP-based genetic labeling marks the fate of type I collagen α1 [Col-α1(I)] expressing aHSCs/myofibroblasts in Col-α1(I)Cre-YFP mice generated by crossing Col-α1(I)Cre and Rosa26f/f-YFP mice. b Col-α1(I)Cre-YFP mice were subjected to CCl4-induced liver injury (1.5 months), then recuperated on cessation of exposure to the injuring agent (for 1 month). Mice were killed and livers were analyzed for the presence of vitamin A positive, yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) positive and vitamin A positive, YFP-negative hepatic stellate cells. c CCl4 induces activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (qHSCs) into aHSCs/myofibroblasts in Col-α1(I)Cre-YFP mice. After CCl4 withdrawal, some aHSCs undergo apoptosis and some become inactivated; the number of YFP-positive inactivated hepatic stellate cells (iHSCs) is less than 100 % of the number of aHSCs [6]. mo month. (Adapted from Kisseleva and Brenner [8•])

Generation of these novel transgenic mice provided a unique tool to study the fate of hepatic myofibroblasts in fibrotic liver. In addition, several studies have used GFAP–Cre mice to successfully target HSCs in the liver. Although these GFAP–Cre mice do not discriminate between qHSC, aHSC, and iHSC (iHSC) phenotypes, they were successfully used to label HSCs for quantification purposes or for HSC-specific gene deletion. Since HSCs and astrocytes share expression of several neural markers, including GFAP, deletion of this gene in the brain might affect the phenotype in the liver.

Characterization of the Novel iHSC Phenotype

Inactivated HSCs (iHSCs) acquire a novel phenotype which has not been previously described (Fig. 1c) [8•]. In particular, iHSCs more rapidly reactivate into myofibroblasts in response to fibrogenic stimuli and more effectively contribute to liver fibrosis. Inactivated HSCs (iHSCs) downregulate α-SMA, Col1a1, Col1a2, TIMP1, and TGF-β receptor 1 and obtain features of quiescent-like HSCs owing to upregulation of PPARγ and Bambi [1••]. Meanwhile, other quiescent-associated genes such as GFAP, Adipor1, Adpf, and Dbp are not reexpressed in iHSCs, suggesting that despite the similarities between qHSCs and iHSCs and their lack of fibrogenic gene expression, iHSCs possess properties distinct from those of qHSCs.

Inactivation of HSCs is associated with reexpression of the lipogenic genes PPARγ, Insig1, and cyclic AMP response element binding protein [31]. Our findings in mice in vivo support previous in vitro studies demonstrating the importance of PPARγ for maintaining and reestablishing the quiescent phenotype [31, 33]. On the basis of comparison of the global gene expression in qHSCs, aHSCs, and iHSCs, we have identified several genes that are differentially expressed in HSCs depending on their stage of activation, and can be used to distinguish iHSCs from qHSCs and aHSCs [1••]. This is of particular importance for identifying inactivation of human HSCs. Our strategy is based on identification of genes similarly and differentially expressed in qHSCs, aHSCs, and iHSCs, and that can be easily detected in a pool of HSCs by flow cytometry. Differential expression of cell surface antigens by different HSC types is illustrated in Fig. 2. Since qHSCs and iHSCs share many features, detection of surface markers may be compared in correlation with induction of phenotype-specific transcription factors, or other proteins.

Comparative analysis of phenotype-specific HSC signature genes may provide further insight into inactivation of HSCs in vivo (Fig. 2). Specifically, we identified seven qHSC-specific genes (that are expressed only in qHSCs), 12 aHSC-specific genes (expressed only in aHSCs), 12 iHSC-specific genes (upregulated in iHSCs), and 12 genes which are upregulated in both qHSCs and I HSCs (and therefore are associated with nonfibrogenic properties of HSCs). Furthermore, the genes Nr1d2, Adipor1, Il17ra, Itga5, Egfr, Crlf1, Il1r1, Rnd1, Csf1r, Il7r, Cntfr, Csf2rb, Cx3cr1, Il10ra, Ly86, Cd36, Mrc1, Agtr1a, Calcr1, Grap, and Ngfr are cell surface receptors, so their expression can be detected using flow cytometry (which can simultaneously detect expression of up to 11 to 12 surface antigens in a single sample), allowing us to confidently identify and isolate live iHSCs. Furthermore, we identified several phenotype-specific transcription factors expressed in HSCs dependent on the stage of activation/inactivation.

Differential expression of cell surface antigens by different hepatic stellate cell types. On the basis of the whole genome microarray, we have identified messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that are specifically upregulated in qHSCs: Nr1d2, adiponectin receptor 1 (Adipor1), adipose-differentiation-related protein (Adfp), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), D site of albumin promoter (albumin D-box) binding protein (Dbp), Prei4, and forkhead box protein J1 (Foxj1). The following mRNAs were specifically upregulated in aHSCs: α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), type I collagen α1 (Col-1α1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), cytokine-receptor-like factor 1 (Crlf1), interleukin-1 receptor type 1 (IL1r1), integrin α5 (Itga5), secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1), lysyl oxidase (Lox), lysyl oxidase like 1 (LoxL2), interleukin-17 receptor A (IL17ra), fos-like antigen 1 (Fosl1), andfolate receptor 1 (Folr1). The following mRNA s were upregulated in iHSCs: Rho family GTPase 1 (Rnd1), colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (Csf1R), interleukin-7 receptor (IL7R), ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor (Cntfr), colony stimulating factor 2 receptor, beta, low-affinity (granulocyte–macrophage) (Csf2rb), CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (Cx3cr1), lymphocyte antigen 86 (Ly86), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 (Cxcl2), FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene (Fos), epidermal growth factor receptor (Egr1), Spi-C transcription factor (Spi-1/PU.1 related) (Spic), and activating transcription factor 3 (Atf3). Several mRNAs were upregulated in both qHSCs and iHSCs: mannose receptor 1 (Mrc1), angiotensin II receptor, type 1 (Agtr1a), calcitonin-receptor-like (Calcrl), GRB2-related adapter protein (Grap), the low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (Ngfr), insulin-induced gene 1 (Insig1), peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), CD36, interleukin-10 receptor α (IL10RA), forkhead box O1 (Foxo1), helix–loop–helix protein (Tal1), and bone morphogenetic protein and activin membrane-bound inhibitor homolog (Xenopus laevis) (Bambi)

Conclusions

Inactivation of myofibroblasts during reversal of fibrosis opens up new prospects for therapy. Hepatic fibrosis is reversible in patients and in experimental models with decreased fibrous scar and disappearance of the myofibroblast population. However, the fate of the myofibroblasts in patients with liver fibrosis is unknown. Although some myofibroblasts undergo death [17], an alternative untested hypothesis is that the myofibroblasts revert to their original quiescent phenotype or obtain a new phenotype. Understanding the origin and biology of fibrogenic myofibroblasts will provide a new target for antifibrotic therapy [21•].

Abbreviations

- aHSCs:

-

Activated HSCs

- α-SMA:

-

α-Smooth muscle actin

- Col-α2(I):

-

Type II collagen α2

- Col-α1(I):

-

Type I collagen α1

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillar acidic protein

- HSCs:

-

Hepatic stellate cells

- iHSCs:

-

Inactivated HSCs

- PPARγ:

-

Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor γ

- qHSCs:

-

Quiescent HSCs

- TGF:

-

Transforming growth factor

- TIMP:

-

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- YFP:

-

Yellow fluorescent protein

References

Recently published papers of particular interest have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Kisseleva T et al (2012) Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during regression of liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:9448–9453. This research article, along with that of Troeger [30••], demonstrated for the first time that aHSCs can become inactivated, initiating a new area of research and providing a new direction for antifibrotic therapy

Bataller R, Brenner DA (2005) Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 115:209–218

Kisseleva T, Brenner DA (2006) Hepatic stellate cells and the reversal of fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21(Suppl 3):S84–S87

Kalluri R, Neilson EG (2003) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112:1776–1784

Gomperts BN, Strieter RM (2007) Fibrocytes in lung disease. J Leukoc Biol 82:449–456

Fallowfield JA et al (2007) Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol 178:5288–5295

Parola M, Marra F, Pinzani M (2008) Myofibroblast—like cells and liver fibrogenesis: emerging concepts in a rapidly moving scenario. Mol Aspects Med 29:58–66

• Kisseleva T, Brenner DA (2013) Inactivation of myofibroblasts during regression of liver fibrosis. Cell Cycle 12:381–382. This review article, along with the 2011 review also by Kisseleva and Brenner [21•], briefly summarizes the current concept of regression of liver fibrosis as well as the disappearance of aHSCs/myofibroblasts by apoptosis and inactivation, and outlines recent advances in antifibrotic therapy

Tang L, Tanaka Y, Marumo F, Sato C (1994) Phenotypic change in portal fibroblasts in biliary fibrosis. Liver 14:76–82

Tuchweber B, Desmouliere A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Rubbia-Brandt L, Gabbiani G (1996) Proliferation and phenotypic modulation of portal fibroblasts in the early stages of cholestatic fibrosis in the rat. Lab Invest 74:265–278

Kisseleva T, Brenner DA (2008) Fibrogenesis of parenchymal organs. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5:338–342

Hammel P et al (2001) Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med 344:418–423

Arthur MJ (2002) Reversibility of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis following treatment for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 122:1525–1528

Kweon YO et al (2001) Decreasing fibrogenesis: an immunohistochemical study of paired liver biopsies following lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 35:749–755

Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, Hughes NR, O’Brien PE (2004) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: improvement in liver histological analysis with weight loss. Hepatology 39:1647–1654

Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA (2004) Decreased fibrosis during corticosteroid therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 40:646–652

Iredale JP et al (1998) Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest 102:538–549

Issa R et al (2004) Spontaneous recovery from micronodular cirrhosis: evidence for incomplete resolution associated with matrix cross-linking. Gastroenterology 126:1795–1808

Issa R et al (2001) Apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells: involvement in resolution of biliary fibrosis and regulation by soluble growth factors. Gut 48:548–557

Uchinami H, Seki E, Brenner DA, D’Armiento J (2006) Loss of MMP 13 attenuates murine hepatic injury and fibrosis during cholestasis. Hepatology 44:420–429

• Kisseleva T, Brenner DA (2011) Anti-fibrogenic strategies and the regression of fibrosis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 25:305–317. This review article, along with the 2013 review also by Kisseleva and Brenner [8•], briefly summarizes the current concept of regression of liver fibrosis as well as the disappearance of aHSCs/myofibroblasts by apoptosis and inactivation, and outlines recent advances in antifibrotic therapy

Iredale JP (2001) Hepatic stellate cell behavior during resolution of liver injury. Semin Liver Dis 21:427–436

Krizhanovsky V et al (2008) Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 134:657–667

Phan SH (2002) The myofibroblast in pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 122:286S–289S

Friedman SL, Bansal MB (2006) Reversal of hepatic fibrosis—fact or fantasy? Hepatology 43:S82–S88

Iredale JP (2007) Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest 117:539–548

Varga J, Brenner D, Phan SE (2005) Fibrosis research. Methods and protocols. Humana, Totowa

Smit JJ et al (1993) Homozygous disruption of the murine mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene leads to a complete absence of phospholipid from bile and to liver disease. Cell 75:451–462

Issa R et al (2003) Mutation in collagen-1 that confers resistance to the action of collagenase results in failure of recovery from CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, persistence of activated hepatic stellate cells, and diminished hepatocyte regeneration. FASEB J 17:47–49

•• Troeger JS et al (2012) Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology 143: 1073–1083, e1022. This research article, along with that of Kisseleva et al. [1••], demonstrated for the first time that aHSCs can become inactivated, initiating a new area of research and providing a new direction for antifibrotic therapy

She H, Xiong S, Hazra S, Tsukamoto H (2005) Adipogenic transcriptional regulation of hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem 280:4959–4967

Tsukamoto H (2005) Fat paradox in liver disease. Keio J Med 54:190–192

Tsukamoto H (2005) Adipogenic phenotype of hepatic stellate cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:132S–133S

Ramirez-Solis R, Liu P, Bradley A (1995) Chromosome engineering in mice. Nature 378:720–724

Perkins AS (2002) Functional genomics in the mouse. Funct Integr Genomics 2:81–91

Sternberg N, Austin S, Hamilton D, Yarmolinsky M (1978) Analysis of bacteriophage P1 immunity by using lambda-P1 recombinants constructed in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75:5594–5598

Sauer B (1998) Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods 14:381–392

Disclosure

Xiao Liu and Jun Xu declare that they have no conflict of interest. David A. Brenner holds a patent for inducing inactivation of fibrogenic myofibroblasts. Tatiana Kisseleva holds a patent for inducing inactivation of fibrogenic myofibroblasts and has received research support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R56 DK088837-01A10).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors. With regard to the authors’ research cited in this article, all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Xu, J., Brenner, D.A. et al. Reversibility of Liver Fibrosis and Inactivation of Fibrogenic Myofibroblasts. Curr Pathobiol Rep 1, 209–214 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40139-013-0018-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40139-013-0018-7