Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) guidelines and strategies suggest escalating treatment, mainly depending on the severity of airflow obstruction. However, some de-escalation of therapy in COPD would be appropriate, although we still do not know when we should switch, step-up or step-down treatments in our patients. Unfortunately, trials comparing different strategies of step-up and step-down treatment (e.g. treatment initiation with one single agent and then further step-up if symptoms are not controlled versus initial use of double or triple therapy, possibly with lower doses of the individual components, or the role of N-acetylcysteine in combination therapy for a step-down approach) are still lacking. In general, there is a large and often inappropriate use of the inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) combination. However, the withdrawal of the ICS in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation can be safe, provided that patients are under regular treatment with long-acting bronchodilators. Maximising the treatment in patients with a degree of clinical instability by including an ICS in the therapeutic regimen is useful to control the disease, but may not be needed during periods of clinical stability. In patients with severe but stable COPD, the withdrawal of the ICS from triple therapy [LABA + long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) + ICS] is possible, but not when the patient has been hospitalised for an acute exacerbation of COPD. We must still establish how long we should wait before withdrawing the ICS. It is still unclear whether the same is true when only the LABA or the LAMA is withdrawn while continuing treatment with the other bronchodilator and the ICS. In any case, we strongly believe that it is always better to avoid a therapeutic step-up progression when it is not needed rather than being forced subsequently into a step-down approach in which the outcome is always unpredictable.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–76.

Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–46.

O’Reilly J, Rudolf M. What’s nice about the new NICE guideline? Thorax. 2011;66:93–6.

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–65.

Wurst KE, Punekar YS, Shukla A. Treatment evolution after COPD diagnosis in the UK primary care setting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105296.

Price D, West D, Brusselle G, et al. Management of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patterns. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:889–904.

Metting EI, Riemersma RA, Sanderman R, et al. Favourable results from a Dutch Asthma/COPD service for primary care. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:14101.

Stallberg B, Janson C, Sundh J, et al. New GOLD recommendations over seven years follow up—changes in symptoms and risk categories [abstract]. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(Suppl 57):P270.

Kim S, Oh J, Kim YI, et al. Differences in classification of COPD group using COPD assessment test (CAT) or modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scores: a cross-sectional analyses. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:35.

Holt S, Sheahan D, Helm C, et al. Little agreement in GOLD category using CAT and mMRC in 450 primary care COPD patients in New Zealand. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14025.

Agusti A, Hurd S, Jones P, et al. FAQs about the GOLD 2011 assessment proposal of COPD: a comparative analysis of four different cohorts. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1391–401.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–38.

Kruis AL, Ställberg B, Jones RC, et al. Primary care COPD patients compared with large pharmaceutically-sponsored COPD studies: an UNLOCK validation study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90145.

Donaldson GC, Müllerova H, Locantore N, et al. Factors associated with change in exacerbation frequency in COPD. Respir Res. 2013;14:79.

Corrado A, Rossi A. How far is real life from COPD therapy guidelines? An Italian observational study. Respir Med. 2012;106:989–97.

Magnoni MS, Rizzi A, Visconti A, Donner CF. AIMAR survey on COPD phenotypes. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2014;9:16.

Soriano JB, Kiri VA, Pride NB, Vestbo J. Inhaled corticosteroids with/without long-acting beta-agonists reduce the risk of rehospitalization and death in COPD patients. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:67–74.

Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New Engl J Med. 2007;356:775–89.

Vestbo J, Vogelmeier C, Small M, Higgins V. Understanding the GOLD 2011 Strategy as applied to a real-world COPD population. Respir Med. 2014;108:729–36.

Choudhury AB, Dawson CM, Kilvington HE, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in people with COPD in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Respir Res. 2007;8:93.

Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJC, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systematic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Jindal SK. Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo for preventing COPD exacerbations: a systematic review and metaregression of randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2010;137:318–25.

Rossi A, van der Molen T, del Olmo R, et al. INSTEAD: a randomised switch trial of indacaterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in moderate COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1548–56.

Fabbri LM, Agusti A. Salmeterol/fluticasone combination instead of indacaterol or vice versa? Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1187–8.

Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15:77.

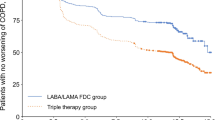

Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1285–94.

Reilly JJ. Stepping down therapy in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1340–1.

Wouters EFM, Postma DS, Fokkens B, et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2005;60:480–7.

Sapey E, Stockley RA. COPD exacerbations. 2: Aetiology. Thorax. 2006;61:250–8.

Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:662–71.

Liesker JJ, Bathoorn E, Postma DS, et al. Sputum inflammation predicts exacerbations after cessation of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD. Respir Med. 2011;105:1853–60.

Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Blood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:48–55.

Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, et al. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:435–42.

Cazzola M, MacNee W, Martinez FJ, et al. Outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:416–69.

Wedzicha JA, Decramer M, Ficker JH, et al. Analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:199–209.

Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, et al. The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:19–26.

Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:449–56.

Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone–salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:545–55.

Short PM, Williamson PA, Elder DH, et al. The impact of tiotropium on mortality and exacerbations when added to inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β-agonist therapy in COPD. Chest. 2012;141:81–6.

Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67:957–63.

Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. Spanish guideline for COPD (GesEPOC). Update 2014. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50(Suppl 1):1–16.

Jamal K, Cooney TP, Fleetham JA, et al. Chronic bronchitis. Correlation of morphologic findings to sputum production and flow rates. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:719–22.

Viegi G, Pistelli F, Sherrill DL, et al. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:993–1013.

Kim V, Han MK, Vance GB, et al. The chronic bronchitic phenotype of COPD: an analysis of the COPDGene Study. Chest. 2011;140:626–33.

Cosio BG, Iglesias A, Rios A, et al. Low-dose theophylline enhances the anti-inflammatory effects of steroids during exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2009;64:424–9.

Ford PA, Durham AL, Russell RE, et al. Treatment effects of low-dose theophylline combined with an inhaled corticosteroid in COPD. Chest. 2010;137:1338–44.

Cyr MC, Beauchesne MF, Lemiere C, Blais L. Effect of theophylline on the rate of moderate to severe exacerbations among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:40–5.

Devereux G, Cotton S, Barnes P, et al. Use of low-dose oral theophylline as an adjunct to inhaled corticosteroids in preventing exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:267.

Cazzola M, Rogliani P, Novelli L, Matera MG. Inhaled corticosteroids for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:2489–99.

Singanayagam A, Chalmers JD, Hill AT. Inhaled corticosteroids and risk of pneumonia: evidence for and against the proposed association. QJM. 2010;103:379–85.

Hanania NA, Calverley PM, Dransfield MT, et al. Pooled subpopulation analyses of the effects of roflumilast on exacerbations and lung function in COPD. Respir Med. 2014;108:366–75.

Rennard SI, Calverley PM, Goehring UM, Bredenbröker D, Martinez FJ. Reduction of exacerbations by the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast—the importance of defining different subsets of patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2011;12:18.

Martinez FJ, Calverley PM, Goehring UM, et al. Effect of roflumilast on exacerbations in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease uncontrolled by combination therapy (REACT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:857–66.

Calverley PM, Martinez FJ, Fabbri L, et al. Does roflumilast decrease exacerbations in severe COPD patients not controlled by inhaled combination therapy? The REACT study protocol. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:375–82.

Tse HN, Raiteri L, Wong KY, et al. High-dose N-acetylcysteine in stable COPD: the 1-year, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled HIACE study. Chest. 2013;144:106–18.

Zheng JP, Wen FQ, Bai CX, et al. Twice daily N-acetylcysteine 600 mg for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PANTHEON): a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:187–94.

Tse HN, Raiteri L, Wong KY, et al. Benefits of high-dose N-acetylcysteine to exacerbation-prone patients with COPD. Chest. 2014;146:611–23.

Cazzola M, Matera MG. N-Acetylcysteine in COPD may be beneficial, but for whom? Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:166–7.

Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Page C, et al. Influence of N-acetylcysteine on chronic bronchitis or COPD exacerbations: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2015. doi:10.1183/16000617.00002215.

Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147:894–942.

Segreti A, Stirpe E, Rogliani P, Cazzola M. Defining phenotypes in COPD: an aid to personalized healthcare. Mol Diagn Ther. 2014;18:381–8.

Lee JH, Lee YK, Kim EK, et al. Responses to inhaled long-acting beta-agonist and corticosteroid according to COPD subtype. Respir Med. 2010;104:542–9.

Beeh KM, Beier J. The short, the long and the “ultra-long”: why duration of bronchodilator action matters in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adv Ther. 2010;27:150–9.

Rabe KF, Timmer W, Sagkriotis A, Viel K. Comparison of a combination of tiotropium plus formoterol to salmeterol plus fluticasone in moderate COPD. Chest. 2008;134:255–62.

Beeh KM, Korn S, Beier J, et al. Effect of QVA149 on lung volumes and exercise tolerance in COPD patients: the BRIGHT study. Respir Med. 2014;108:584–92.

Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Page CP, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the interaction between aclidinium bromide and formoterol fumarate on human isolated bronchi. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;745:135–43.

Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Segreti A, et al. Translational study searching for synergy between glycopyrronium and indacaterol. COPD. 2015;12:175–81.

Cazzola M, Page CP, Calzetta L, Matera MG. Emerging anti-inflammatory strategies for COPD. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:724–41.

Calzetta L, Matera MG, Cazzola M. Pharmacological interaction between LABAs and LAMAs in the airways: optimizing synergy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;761:168–73.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Cazzola is a consultant at Chiesi Farmaceutici, Zambon and Novartis, and has undertaken research funded by Novartis, AstraZeneca and Almirall. He is also a member of the Novartis, GSK, AstraZeneca, Zambon, Mundipharma and Boehringer Ingelheim speaker bureau. P. Rogliani is a member of the AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim speaker bureau. M. G. Matera has undertaken research funded by Novartis and is a member of the Boehringer Ingelheim speaker bureau.

Funding

This manuscript was not funded/sponsored, and no writing assistance was utilised in its production.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cazzola, M., Rogliani, P. & Matera, M.G. Escalation and De-escalation of Therapy in COPD: Myths, Realities and Perspectives. Drugs 75, 1575–1585 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-015-0450-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-015-0450-6