Abstract

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely recommended and prescribed to treat pain in osteoarthritis. While measured to have a moderate effect on pain in osteoarthritis, NSAIDs have been associated with wide-ranging adverse events affecting the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal systems. Gastrointestinal toxicity is found with all NSAIDs, which may be of particular concern when treating older patients with osteoarthritis, and gastric adverse events may be reduced by taking a concomitant gastroprotective agent, although intestinal adverse events are not ameliorated. Cardiovascular toxicity is associated with all NSAIDs to some extent and the degree of risk appears to be pharmacotherapy specific. An increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and heart failure is observed with all NSAIDs, while an elevated risk of hemorrhagic stroke appears to be restricted to the use of diclofenac and meloxicam. All NSAIDs have the potential to induce acute kidney injury, and patients with osteoarthritis with co-morbid conditions including hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes mellitus are at increased risk. Osteoarthritis is associated with excess mortality, which may be explained by reduced levels of physical activity owing to lower limb pain, presence of comorbid conditions, and the adverse effects of anti-osteoarthritis medications especially NSAIDs. This narrative review of recent literature identifies data on the safety of non-selective NSAIDs to better understand the risk:benefit of using NSAIDs to manage pain in osteoarthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Although effective against inflammatory-mediated pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with multiple class-specific toxicities affecting the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal systems. Some adverse effects are related to the class mechanism of action, while others appear to be pharmacotherapy specific. |

The choice of any agent should be considered on an individual patient basis in osteoarthritis to provide adequate symptom relief while minimizing unwanted side effects. |

1 Introduction

Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are universally recommended in international and national guidelines for the management of pain in osteoarthritis (OA) in patients presenting with severe pain and musculoskeletal pain, and those who are unresponsive to merely paracetamol (acetaminophen) [1,2,3,4,5]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are one of the most widely used drugs in OA: over 50% of patients with OA in USA are prescribed NSAIDs, and among patients with OA across Europe using prescription medications (47%), 60% of those received NSAIDs [6, 7]. Non-prescription NSAIDs were the most frequently reported medications (27%) used by participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative with symptomatic radiographic knee OA, even for those aged > 75 years [8]. While there was a reduction in prescription NSAID use in the older population, in line with recommendations that oral NSAIDs should not be prescribed to those aged older than 75 years [9], the use of over-the-counter NSAIDs remained worryingly high in this age group [8].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have a moderate effect on pain in OA, measured as an effect size of 0.37 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.26–0.40) in a meta-analysis of ten randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of short-term treatment lasting for 6–12 weeks [10]. Although effective, a systematic literature review and meta-analysis up to 2011 found an increased risk of serious gastrointestinal (GI), cardiovascular (CV), and renal harms with NSAIDs compared with placebo [11]. Older patients have an increased risk of these adverse events (AEs) and are more likely to receive polypharmacy that can potentially interact with NSAIDs [12]. Older patients are more likely to have CV disease and age-related decline in renal function, increasing the risk of CV, hematologic, and renal AEs. In evaluation of the relative efficacy and safety of NSAIDs, guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee OA from the Osteoarthritis Research Society International consider the use of oral non-selective NSAIDs (nsNSAIDs) appropriate in individual patients with OA without comorbidities, but uncertain in individuals with a moderate co-morbidity risk and not appropriate for individuals with a high co-morbidity risk [2]. In addition, management guidelines from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis, and Musculoskeletal Diseases recommend that NSAID use be limited to the lowest effective dose for the shortest time necessary to control symptoms, either intermittently or in longer cycles rather than in long-term use [1, 13]. Topical NSAIDs may be used in preference to oral NSAIDs particularly in patients aged ≥ 75 years as they are demonstrated to have similar efficacy to the oral medications with a reduced risk of systemic AEs [1, 13].

In this narrative literature review, we have identified data on the safety of traditional nsNSAIDs (naproxen, ibuprofen, diclofenac) published since the Cochrane review of 2011 [11], to identify current understanding on the relative risk:benefit of the use of nsNSAIDs to manage pain in OA. We discuss the safety of cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors as a specific class of NSAIDs (e.g., celecoxib, rofecoxib) in relation to the safety of nsNSAIDs, and in more detail as the subject of a separate systematic literature review and meta-analysis, which is presented in the subsequent article of this supplement [14].

2 Mortality in Osteoarthritis

There is evidence for an increase in all-cause mortality and CV mortality in patients with lower limb OA, which is more pronounced in studies including symptomatic patients. A systematic review of mortality in OA, which found seven studies that provided data on either mortality or survival in people with OA, identified an overall increase in mortality among persons with OA compared with the general population [15]. Risk factors for mortality in people with OA were identified as age, polyarticular disease, and comorbidities. Increased cause-specific mortality from CV and GI disorders was observed in some studies. Possible explanations for the excess mortality in OA include reduced levels of physical activity owing to lower limb OA, the presence of comorbid conditions such as CV disease, as well as adverse effects of medications, particularly NSAIDs [15,16,17,18,19,20].

A recent population-based cohort study of general practice in the UK identified 1163 patients (aged > 35 years) with symptoms and radiologic confirmation of OA of the knee or hip, with a median follow-up of 14 years [21, 22]. Patients with OA were found to be at a higher risk of death compared with the general population. Excess mortality was observed for all disease-specific causes of death (standardized mortality ratio = 1.55, 95% CI 1.41–1.70), but was particularly pronounced for CV causes (standardized mortality ratio = 1.71, 95% CI 1.49–1.98) [21]. Mortality was found to increase with age, male sex, co-morbidity (diabetes mellitus, cancer, CV disease), and walking disability. The more severe the walking disability, the higher the risk of death [21, 23].

The association of knee OA with premature mortality in the community has been assessed in an international meta-analysis of data from individual participant data included in six prospective population-based cohorts [24]. Subjects were divided into four knee OA categories depending on the presence of radiographic OA and/or symptomatic OA, with or without pain. Subjects with knee symptomatic radiographic OA had a significant 19% increased association with premature mortality independent of age, sex, and race, compared with subjects free from OA (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.19, 95% CI 1.04–1.37) [24].

In another systematic review with a meta-analysis, the risk of all-cause and CV mortality was assessed using adjusted HRs for joint specific (hand, hip, and knee) and joint non-specific OA [25]. The meta-analysis of seven studies (OA = 10,018/non-OA = 18,541) with a median 12-year follow-up, reported no increased risk of any-cause mortality in those with OA (HR = 1.10, 95% CI 0.97–1.25). However, after removing data on hand OA, a significant association between OA and mortality was observed (HR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.08–1.28). In addition, the analysis found a significant higher risk of overall mortality for (1) studies conducted in Europe, (2) patients with multi-joint OA; and (3) a radiologic diagnosis of OA. Osteoarthritis was associated with significantly higher CV mortality (HR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.34) [25]. Painful knee but not hand OA is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and CV mortality, suggesting that knee pain more than structural changes in OA is the main driver of excess mortality in patients with OA [26]. Although hand OA is not linked with mortality, symptomatic hand OA is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (HR = 2.26, 95% CI 1.22–4.18), which suggest an effect of pain, which may be a possible marker of inflammation [27]. Furthermore, coronary heart disease is associated with a worse clinical outcome for hand OA over 2.6 years (odds ratio = 2.91, 95% CI 1.02–8.26), as identified in a post-hoc analysis of patients included in a phase III randomized trial of strontium ranelate [28].

3 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Mechanism of Action and Potential for Adverse Events

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs exert their effects by inhibiting the COX enzymes, which are the first step in the conversion of arachidonic acid into various prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and prostacyclins. Two main isoforms of COX enzymes exist: COX-1 and COX-2. Cyclo-oxygenase-1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues and physiologically functions in the maintenance of renal function, protection of the gastric mucosa, and in the regulation of platelet aggregation. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 is considered to be inducible by proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors. The use of nsNSAIDs is limited by AEs associated with inhibition of the COX-1 enzyme, particularly GI ulcers and bleeding (Fig. 1) [29].

Thus, selective COX-2 inhibitors were designed to reduce the GI toxicity associated with nsNSAIDs; however, they may have a higher incidence of CV toxicity by altering the normal balance in the production of prostacyclin vs. thromboxane by different cell types in the CV system. There is also evidence from animal studies of a difference between NSAIDs in direct toxicity on the heart via reactive oxygen species production from mitochondria [30]. This can account for the increased incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke associated with some nsNSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors. An increased risk of CV AEs has been identified in observational studies with some NSAIDs, such as diclofenac [17]. While among the COX-2 inhibitors, rofecoxib was associated with an increased risk of acute coronary syndromes, and was subsequently withdrawn from the therapeutic market in 2004 [31]. Non-selective NSAIDs, that block either COX-1 or COX-2, can also interfere with the production of prostaglandins that play an important role in maintaining renal blood flow in patients with compromised renal function.

4 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Gastrointestinal Adverse Events

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are known to pose a risk to the GI system, particularly nsNSAIDs, and COX-2 inhibitors were developed to reduce the GI AEs of NSAIDs. However, all NSAID regimens, including nsNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, are found to increase upper GI complications (COX-2 inhibitors rate ratio [RR] = 1.81, 95% CI 1.17–2.81; p = 0.0070; diclofenac RR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.16–3.09; p = 0.0106; ibuprofen RR = 3.97, 95% CI 2.22–7.10; p < 0.0001; and naproxen RR = 4.22, 95% CI 2.71–6.56, p < 0.0001) [32].

A meta-analysis of six RCTs with a total of 6219 patients revealed that COX-2 inhibitors were similar to nsNSAIDs in combination with the gastroprotectant proton pump inhibitors in regard to upper GI AEs, GI symptoms, and CV AEs [33]. There was no difference in upper GI AEs between COX-2 inhibitors and nsNSAIDs with concurrent use of proton pump inhibitors (relative risk = 0.61, 95% CI 0.34–1.09] (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in GI symptoms (relative risk = 1.10, 95% CI 0.88–1.39) and CV AEs (relative risk = 1.67, 95% CI 0.78–3.59) between the two groups. There was heterogeneity of the studies (p = 0.0003, I2 = 79%).

Reproduced from Wang et al. [33]; copyright permission granted by Wolters Kluwer Health Inc, 2018

Risk of upper gastrointestinal adverse events with cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors (Coxibs) vs. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) plus proton pump inhibitor (PPI). CI confidence interval, M-H Mantel-Haenszel.

Gastrointestinal toxicity is an important consideration when selecting an nsNSAID for elderly patients with arthritis. A retrospective pooled analysis of 9461 patients aged ≥ 65 years with OA, rheumatoid arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis from 21 randomized parallel-group trials of ≥ 2 weeks duration with at least one celecoxib arm (200–400 mg/day) and one nsNSAID (naproxen, ibuprofen, or diclofenac) arm found celecoxib to be better tolerated than nsNSAIDs for GI AEs [34]. The combined incidence of GI AEs was reported by significantly fewer patients treated with celecoxib (16.7%) than naproxen (29.4%; p < 0.0001), ibuprofen (26.5%; p = 0.0016), or diclofenac (21.0%; p < 0.0001). The discontinuation rate owing to GI AEs was significantly lower for celecoxib (4.0%) vs. naproxen (8.1%; p < 0.0001) and ibuprofen (7.3%; p < 0.05), but not diclofenac (4.2%; p = 0.75).

5 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Cardiovascular Adverse Events

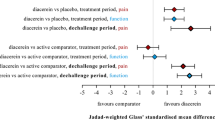

It was thought that the selectivity of NSAIDs for the COX-2 enzyme may govern the CV toxicity profile, possibly owing to an imbalance in COX-1 and COX-2 activities. However, CV risk also exists for the nsNSAIDs, and thus CV toxic effects may result from differences in physiochemical properties between different NSAIDs that requires further investigation. A meta-analysis of 26 RCTs compared the incidence of CV endpoints between different NSAIDs (Fig. 3), finding the highest risk with rofecoxib [35]. In the Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety vs Ibuprofen Or Naproxen (PRECISION) trial, 24,081 patients were randomly assigned to celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for a mean treatment duration of 20 months and mean follow-up of 34 months [36]. Celecoxib (209 ± 37 mg) was non-inferior to naproxen (852 ± 103 mg) or ibuprofen (2045 ± 246 mg) for the primary composite outcome of CV death (including hemorrhagic death), non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke in patients with arthritis at moderate CV risk. However, during the trial, 69% of all patients stopped taking the study drug, and the primary event rate was low: less than 3% of patients in each treatment group in the intention-to-treat analysis, and < 2% in the on-treatment analysis.

Reproduced from Gunter et al. [35]; Copyright permission granted by John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2018

Risk of cardiovascular outcomes with all non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). CV cardiovascular, MI myocardial infarction. Each NSAID was compared against all other NSAIDs in the study for each outcome. NSAIDs denoted by (*) represent statistically significant findings.

5.1 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Acute Myocardial Infarction

A population‐based cohort study was undertaken to characterize the determinants, time course, and risks of acute MI associated with the use of oral NSAIDs in real-world use. The study employed a systematic review followed by a one-stage Bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data from four trials identified from database searches from inception to November 2013 that included five NSAIDs (ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, celecoxib, rofecoxib) [37]. There was an increased risk of MI with all NSAIDs; the risk with the nsNSAIDs was similar, and the risk highest for rofecoxib, and lowest for celecoxib. The risk was greatest during the first month of NSAID use and with higher doses. Odds ratios (95% CI) for the most common current daily dose vs. no current exposure for individual NSAIDs are shown in Table 1 [37]. The OR of acute MI for current exposure to NSAIDs, taken for any duration of time before the index date, indicates an associated increase in risk of 15% for celecoxib (200 mg), 25% for naproxen (500 mg), 35% for diclofenac (100 mg), 40% for ibuprofen (1200 mg), and 55% for rofecoxib (25 mg). Notably, the MI risk with celecoxib appeared to depend on continuously using the drug for more than 30 days, whereas for ibuprofen, rofecoxib, diclofenac, and naproxen, a heightened MI risk occurred within 7 days of use. The absolute risk of MI associated with NSAID use was estimated to be about 0.5–1% per year [37]. Although this absolute MI risk increase is small, NSAID use is very prevalent in older adults.

5.2 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Incident Heart Failure

The use of NSAIDs may be associated with an increased risk of heart failure (HF) as a result of salt and fluid retention secondary to the reduction in prostaglandin synthesis. To assess the risk of incident HF with the use of NSAIDs, a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reporting risk ratio, OR, HR, or standardized incidence ratio (with 95% CI) comparing the risk of incident HF in NSAID users vs. non-users was conducted. The database searches from inception until April 2015 identified seven studies that included 7,543,805 participants using NSAIDs for any indication [38]. Use of NSAIDs was associated with a higher risk of developing HF, with a pooled risk ratio of 1.17 (95% CI 1.01–1.36).

5.3 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Cerebrovascular Adverse Events

The use of NSAIDs may be associated with an increased risk of stroke, one of the major subtypes of CV disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ten observational case-controlled studies identified by database searches from inception until August 2015 has assessed the risk of hemorrhagic stroke associated with NSAID use for any indication [39]. As a single group, NSAID use was associated with a small but insignificant risk of hemorrhagic stroke (pooled risk ratio = 1.09, 95% CI 0.98–1.22) [Table 2]. However, analysis of individual NSAIDs revealed a significantly increased risk with diclofenac (risk ratio 1.27, 95% CI 1.02–1.59) and meloxicam (risk ratio 1.27, 95% CI 1.08–1.50, respectively). Inhibition of COX enzymes by NSAIDs could result in vasoconstriction and increased peripheral arterial resistance, and the inhibition of the COX-2 enzyme could lead to salt/fluid retention, the combination of which could lead to hypertension, the prime risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage. This may explain the significant risk observed with diclofenac and meloxicam, two nsNSAIDs with the highest COX-2 selectivity [40]. The highest risk estimate was found in rofecoxib users, even though the pooled risk ratio did not achieve statistical significance (risk ratio = 1.35, 95% CI 0.88–2.06) probably owing to the small number of rofecoxib users as this drug was withdrawn from the market in 2004 [39].

6 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Acute Kidney Injury

The use of NSAIDs can cause acute kidney injury (AKI) by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins and consequently reducing the blood flow to the kidneys and/or induction of interstitial nephritis. Acute kidney injury is a rapid and sustained abruption of the renal function causing accumulation of waste products (e.g., urea, creatinine), which is typically dose and duration dependent, and reversible. Although patients with normal renal function are unlikely to develop AKI secondary to taking NSAIDs those with a history of hypertension, HF, or diabetes have a higher chance of developing these complications [41]. The risk of AKI is particularly high in the first 30 days after initiation of therapy with NSAIDs. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users have a three-fold greater risk of developing clinical AKI compared with non-NSAID users in the general population [41]. While the association between AKI and the use of NSAIDs is well known, less is known about the comparative risk of individual NSAIDs.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of five cohort studies that reported relative risk, HR, or standardized incidence ratio (with 95% CI) comparing AKI risk in NSAID users vs. non-users was conducted. Pooled risk ratios were calculated for seven nsNSAIDs and two COX-2 inhibitors (indomethacin, piroxicam, ibuprofen, naproxen, sulindac, diclofenac, meloxicam, rofecoxib, and celecoxib) [42]. A statistically significant elevation in AKI risk was demonstrated among most of the nsNSAIDs. Pooled risk ratios were fairly consistent among individual nsNSAIDs, ranging from 1.58 to 2.11. Differences between pooled risk ratios did not reach statistical significance (p ≥ 0.19 for each comparison). Elevated AKI risk was also observed with rofecoxib, celecoxib, and two nsNSAIDs with higher COX-2 selectivity (diclofenac and meloxicam) although this did not reach statistical significance [32].

7 Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Falls and Fractures

Falls and resulting fractures are a leading cause of morbidity/mortality in the elderly. A nested case-control study was conducted using electronic medical records (2001–9) to determine if there was an association with fall events among elderly patients with OA (n = 13,354; aged 65–89 years) [43]. The likelihood of experiencing a fall/fracture was highest in patients prescribed opioid analgesics, which may reflect the known effects of opioids on the central nervous system, which is often compounded by age [44, 45]. The risk of falls was elevated with COX-2 inhibitors compared with nsNSAIDs (odds ratio = 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.6). A cohort study of exposure to analgesics in patients with OA (80% of cohort; n = 11,434) or RA (n = 1406) [mean age 80 years, 85% female] found an incident rate of 26 falls with nsNSAIDs, 18 falls with COX-2 inhibitors, and 41 falls with opioids [46]. The use of COX-2 inhibitors and nsNSAIDs resulted in a similar risk for fracture, while fracture risk was elevated with opioid use (HR = 4.47, 95% CI 3.12–6.41), as was the risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.87, 95 CI 1.39–2.53) compared with the use of nsNSAIDs. The proposed mechanism for NSAID-induced bone loss entails altered mechano-sensing by osteocytes under circumstances of altered nitrous oxide production; although further research on this topic is needed, nitrous oxide donors such as isosorbide dinitrate are thought to have beneficial effects on bone density [47].

8 Conclusions

In this narrative literature review, we have sought to unravel recent data on the safety of nsNSAIDs to identify current understanding on the relative risk:benefit of nsNSAIDs used to manage pain in OA. Our key findings are summarized in the Panel of practice points, which is intended to assist the reader when making therapeutic decisions on the appropriate choice of medications for individual patients with OA. All NSAIDs have the potential for GI and CV toxicity through their action on the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. If nsNSAIDs are taken with a gastroprotective proton pump inhibitor, the upper GI toxicity is attenuated and similar to that found with a COX-2-specific NSAID. There is an increased risk of acute MI with all NSAIDs, which may occur within 7 days of use. The risk of incident HF is elevated with all NSAIDs. An increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke appears to be limited to the nsNSAIDs with the highest COX-2 selectivity, diclofenac and meloxicam. All nsNSAIDs are associated with an increased risk of AKI. While opioid analgesics are associated with an increased risk of falls and fractures, NSAIDs are associated to a lesser extent. The excess mortality observed with OA may be attributable, in part, to treatment algorithms including NSAIDs, paracetamol, and possibly COX-2 inhibitors. Consequently, multiple strategies to control symptoms in OA should be considered on an individual patient basis.

Panel: Practice Points |

|---|

All non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have the potential to induce adverse events through their actions on the cyclo-oxgygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 enzymes, including: gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding (COX-1), hypertension and kidney injury (COX-1 and COX-2), and cardiovascular (CV) events [myocardial infarction and stroke] (COX-2 > COX-1) |

The rate of upper gastrointestinal complications (ulcers and bleeding) is increased with all NSAIDs; the upper gastrointestinal toxicity of non-selective NSAIDs may be reduced by concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors to a level similar to that of COX-2-selective NSAIDs |

It would appear that CV risk may be drug specific and further research is needed to determine the extent of NSAID-induced CV adverse events for both the class and individual NSAIDs. Naproxen does not confer better CV outcomes than other NSAIDs |

There is an increased risk of myocardial infarction with all NSAIDs, albeit small, which can occur within 7 days of initiation of non-selective NSAIDs |

There is a higher risk of heart failure with all NSAIDs, likely as a result of sodium and water retention through inhibition of COX-driven prostaglandin synthesis |

There is an increased risk of stroke with certain non-selective NSAIDs that exhibit high COX-2 selectivity, namely diclofenac and meloxicam |

The risk of acute kidney injury is higher among NSAID users than the general population, and appears to be consistently high for all non-selective NSAIDs |

In elderly patients with osteoarthritis taking analgesics, NSAIDs are associated with a lower risk of falls and fractures than opioids |

References

Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, Branco J, Brandi ML, Guillemin F, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(3):253–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.014.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(3):363–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):465–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21596.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoarthritis care and management in adults: Methods, evidence and recommendations. National Clinical Guideline Centre. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014: Report no. CG177.

Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma JWJ, Dieppe P, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–55. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2003.011742.

Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Use and costs of prescription medications and alternative treatments in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in community-based settings. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):550–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00532.x.

Kingsbury SR, Gross HJ, Isherwood G, Conaghan PG. Osteoarthritis in Europe: impact on health status, work productivity and use of pharmacotherapies in five European countries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(5):937–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket463.

Kingsbury SR, Hensor EM, Walsh CA, Hochberg MC, Conaghan PG. How do people with knee osteoarthritis use osteoarthritis pain medications and does this change over time? Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R106. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4286.

American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. Pain Med. 2009;10(6):1062–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00699.x.

Lee C, Hunsche E, Balshaw R, Kong SX, Schnitzer TJ. Need for common internal controls when assessing the relative efficacy of pharmacologic agents using a meta-analytic approach: case study of cyclooxygenase 2-selective inhibitors for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(4):510–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21328.

Chou R, McDonagh MS, Nakamoto E, Griffin J. Analgesics for osteoarthritis: an update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 38. October 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC076-EF. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65646/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK65646.pdf. Accessed 27 Apr 2018.

Barkin RL, Beckerman M, Blum SL, Clark FM, Koh EK, Wu DS. Should nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) be prescribed to the older adult? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(10):775–89. https://doi.org/10.2165/11539430-000000000-00000.

Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier J-P, Maheu E, Rannou F, Branco J, et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis: from evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(Suppl. 4S):S3–11.

Curtis E, Fuggle N, Shaw S, Spooner L, Ntani G, Parsons C, et al. Safety of cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors in osteoarthritis: outcomes of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(Suppl. 1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00664-x.

Hochberg MC. Mortality in osteoarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(5 Suppl. 51):S120–4.

Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7553):1302–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302.

McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA. 2006;296(13):1633–44. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.13.jrv60011.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Varas-Lorenzo C, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98(3):266–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_302.x.

Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, Jolicoeur E, Boucher M, Joyce J, et al. Gastrointestinal safety of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(7):818–28, 828.e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.011 (quiz 768).

Laine L, White WB, Rostom A, Hochberg M. COX-2 selective inhibitors in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;38(3):165–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.10.004.

Nuesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S, Williams S, Iff S, Juni P. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1165. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d1165.

Cooper C, Arden NK. Excess mortality in osteoarthritis. BMJ. 2011;342:d1407. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d1407.

Hawker GA, Croxford R, Bierman AS, Harvey PJ, Ravi B, Stanaitis I, et al. All-cause mortality and serious cardiovascular events in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a population based cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91286. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091286.

Leyland KM, Gates LS, Sanchez-Santos MT, Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Collins G, et al. The association of knee osteoarthritis and premature mortality in the community: an international individual patient level meta-analysis in six prospective cohorts. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(Suppl. 1):abstract no. OC10.

Veronese N, Cereda E, Maggi S, Luchini C, Solmi M, Smith T, et al. Osteoarthritis and mortality: a prospective cohort study and systematic review with meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(2):160–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.04.002.

Kluzek S, Sanchez-Santos MT, Leyland KM, Judge A, Spector TD, Hart D, et al. Painful knee but not hand osteoarthritis is an independent predictor of mortality over 23 years follow-up of a population-based cohort of middle-aged women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(10):1749–56. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208056.

Haugen IK, Ramachandran VS, Misra D, Neogi T, Niu J, Yang T, et al. Hand osteoarthritis in relation to mortality and incidence of cardiovascular disease: data from the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):74–81. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203789.

Courties A, Sellam J, Maheu E, Cadet C, Barthe Y, Carrat F, et al. Coronary heart disease is associated with a worse clinical outcome of hand osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. RMD Open. 2017;3(1):e000344. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000344.

Harirforoosh S, Asghar W, Jamali F. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal complications. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;16(5):821–47.

Ghosh R, Hwang SM, Cui Z, Gilda JE, Gomes AV. Different effects of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs meclofenamate sodium and naproxen sodium on proteasome activity in cardiac cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;94:131–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.03.016.

Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1092–102. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050493.

Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration, Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, Abramson S, Arber N, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60900-9.

Wang X, Tian HJ, Yang HK, Wanyan P, Peng YJ. Meta-analysis: cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors are no better than nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with proton pump inhibitors in regard to gastrointestinal adverse events in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(10):876–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e328349de81.

Mallen SR, Essex MN, Zhang R. Gastrointestinal tolerability of NSAIDs in elderly patients: a pooled analysis of 21 randomized clinical trials with celecoxib and nonselective NSAIDs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(7):1359–66. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2011.581274.

Gunter BR, Butler KA, Wallace RL, Smith SM, Harirforoosh S. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced cardiovascular adverse events: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(1):27–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12484.

Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, Luscher TF, Libby P, Husni ME, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2519–29. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611593.

Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B, Nadeau L, Helin-Salmivaara A, Garbe E, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: Bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. 2017;357:j1909. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1909.

Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Thongprayoon C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of incident heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(2):111–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22502.

Ungprasert P, Matteson EL, Thongprayoon C. Nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Stroke. 2016;47(2):356–64. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011678.

Antman EM, DeMets D, Loscalzo J. Cyclooxygenase inhibition and cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2005;112(5):759–70. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.105.568451.

Fairweather J, Jawad AS. Cardiovascular risk with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): the urological perspective. BJU Int. 2012;110(11):E437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11679_4.x.

Ungprasert P, Cheungpasitporn W, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(4):285–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2015.03.008.

Rolita L, Spegman A, Tang X, Cronstein BN. Greater number of narcotic analgesic prescriptions for osteoarthritis is associated with falls and fractures in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):335–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12148.

Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA. Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(6):571–84.

Mercadante S, Ferrera P, Villari P, Casuccio A. Opioid escalation in patients with cancer pain: the effect of age. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;32(5):413–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.015.

Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Lee J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):1968–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391.

Misra D, Peloquin C, Kiel DP, Neogi T, Lu N, Zhang Y. Intermittent nitrate use and risk of hip fracture. Am J Med. 2017;130(2):229.e15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.09.006.

Acknowledgements

This article is written on behalf of the ESCEO Working Group on the safety of anti-osteoarthritis medications: Nasser Al-Daghri, Nigel Arden, Bernard Avouac, Olivier Bruyère, Roland Chapurlat, Philip Conaghan, Cyrus Cooper, Elizabeth Curtis, Elaine Dennison, Nicholas Fuggle, Gabriel Herrero-Beaumont, Germain Honvo, Margreet Kloppenburg, Stefania Maggi, Tim McAlindon, Alberto Migliore, Ouafa Mkinsi, François Rannou, Jean-Yves Reginster, René Rizzoli, Roland Roth, Thierry Thomas, Daniel Uebelhart, and Nicola Veronese. The authors would like to express their most sincere gratitude to Dr. Lisa Buttle for her invaluable help with the manuscript preparation. Dr. Lisa Buttle was entirely funded by ESCEO asbl, Belgium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The Working Group was entirely funded by ESCEO, a Belgian not-for-profit organization. ESCEO receives unrestricted educational grants, to support its educational and scientific activities, from non-governmental organizations, not-for-profit organizations, and non-commercial and corporate partners. The choice of topics, participants, content, and agenda of the working groups as well as the writing, editing, submission, and reviewing of the manuscript is under the sole responsibility of ESCEO, without any influence from third parties.

Conflict of interest

Olivier Bruyère reports grants from Biophytis, IBSA, MEDA, Servier, SMB, and Theramex, outside of the submitted work. Cyrus Cooper reports personal fees from Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Takeda, and UCB, outside of the submitted work. Jean-Yves Reginster reports grants from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, and Radius Health (through institution), consulting fees from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, Radius Health, and Pierre Fabre, fees for participation in review activities from IBSA-Genevrier, MYLAN, CNIEL, Radius Health, and Teva, payment for lectures from AgNovos, CERIN, CNIEL, Dairy Research Council, Echolight, IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Pfizer Consumer Health, Teva, and Theramex, outside of the submitted work. François Rannou reports grants from APHP, INSERM, University Paris Descartes, and Arthritis (Road Network), and consulting fees from Pierre Fabre, Expanscience, Thuasne, Servier, Genevrier, Sanofi Aventis, and Genzyme, outside of the submitted work. Roland Chapurlat, Nasser Al-Daghri, Gabriel Herrero-Beaumont, Roland Roth, and Daniel Uebelhart have not conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, C., Chapurlat, R., Al-Daghri, N. et al. Safety of Oral Non-Selective Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Osteoarthritis: What Does the Literature Say?. Drugs Aging 36 (Suppl 1), 15–24 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00660-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00660-1