Abstract

Purpose

Orthorexia Nervosa (ON) is described as an extreme level of preoccupation around healthy eating, accompanied by restrictive eating behaviors. During the years, different assessment instruments have been developed. The aim of the study is to adapt into Italian the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (I-DOS) and to test its psychometric properties.

Method

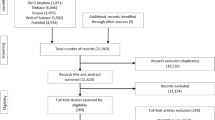

A total sample of 422 volunteer university students (mean age = 20.70 ± 3.44, women 71.8%) completed a group of self-report questionnaires in large group sessions during their lecture time. The scales assessed ON (the I-DOS and the Orhto-15), disordered eating (Disordered Eating Questionnaire, DEQ), depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II, BDI-II), obsessive and compulsive symptoms (Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised, OCI-R), and self-reported height and weight.

Results

The fit of the unidimensional structure and reliability of the I-DOS was tested trough Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) as well as its criterion validity computing correlation coefficients among Ortho-15, DEQ, BDI-II, OCI-R, BMI. Analyses confirmed the unidimensional structure of the I-DOS with acceptable or great fit indices (CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.978; SRMR = 0.043; RMSEA = 0.076) and the strong internal consistency (α = 0.888). The correlations path supported the criterion validity of the scale. The estimated total prevalence of both ON and ON risk was 8.1%.

Conclusions

This 10-item scale appears to be a valid and reliable measure to assess orthorexic behaviors and attitudes.

Level of evidence

Level V, descriptive cross-sectional study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 90’s Bratman [1] described for the first time Orthorexia Nervosa (ON) as an extreme level of preoccupation around healthy eating, accompanied by restrictive eating behaviors. The term comes from the Greek “orthos” (correct, right) and “orexia” (appetite, hunger). The portmanteau term thus describes an excessive concern related to eating healthy foods to avoid adverse health outcomes [2]. Bratman considered it to be a disorder to the extent that the pursuit of healthy foods negatively impacted upon other areas of life such as work and relationships and was impairing and associated with significant changes in lifestyle [2, 3], as it is also associated to the reluctance to eat outside to avoid eating certain types of foods considered unhealthy, extreme preoccupation around eating only organic or “pure” foods, and excessive concern related to food quality [4].

Although the research on ON is currently flourishing, several limitations have been highlighted by a narrative review of the literature by Cena and colleagues [5], which accurately explores the main features and the problems sill related to this construct such as the terms used to describe and define ON and healthy eating, and the definition of clear and shared diagnostic criteria.

Despite the lack of consensus among the definition of ON by different authors, and the fact that it has not yet been included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [6], several instruments assessing this construct have been developed over the years [7].

Recently, Meule and colleagues [7] compared four of the most popular self-report scales for measuring ON: Bratman's Orthorexia Test (BOT) [2], the ORTO-15 [3], the Eating Habits Questionnaire (EHQ) [8], and the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS) [9], examining their factor structure, internal reliability, and the intercorrelations between them. Three of these scales (BOT, EHQ, and DOS) demonstrated to be valid and reliable instruments to assess orthorexia nervosa and the high intercorrelations across them (rs > 0.70) indicated that they essentially measure the same construct [10, 11]. Furthermore, in order to overcome the statistical limitations of the ORTO-15 [3] a revised version of this scale has been recently developed, the ORTO-R [12].

The aim of the present study is to adapt the Italian version of the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (I-DOS) and to test its psychometric properties. The original German version of the scale was developed in 2015, but it was quickly adapted into English [13], Chinese [14], Spanish [15], Portuguese [16], Polish [17], and recently French [18]. The results from these studies converge in evidencing the good fit of the one factor structure of the scale and its good internal consistency (ranging between α = 0.84 to 0.88). In the present study, it was adapted into Italian and its psychometric properties were tested through Confirmatory Factor Analysis and correlations with other scales.

Method

Participants and procedure

A total sample of 422 young adults (mean age = 20.70 ± 3.44, women 71.8%) were recruited among the student community of Sapienza University of Rome, using a convenience sampling procedure. Both graduate or undergraduate students volunteered to participate in the study and provided a written informed consent. All participants completed a battery of self-report questionnaires in large group sessions during their lecture time between September 2019 and January 2020. The session lasted about 30 min. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome.

Measures

ON was measured using the I-DOS and the most widely used ORTO-15 [3], thus testing the convergent validity: (a) The Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala (DOS) [9]—the German version demonstrated good psychometric properties, with Cronbach α = 0.84 and test–retest reliability, r = 0.79. The scale (I-DOS) was translated and back-translated [19] and psychometric properties assessed. The translation phase involved three steps: an initial translation to Italian; a back-translation of the Italian version to the German version; a comparison of the original DOS scale with the back-translated version [20, 21]. Cronbach’s α of the Italian translation was 0.888, showing a strong internal consistency. The scale consists of 10 items assessing orthorexic behaviors and attitudes using a 4 a four-point Likert-scale from “this applies to me” (4 points) to “this does not apply to me” (1 point). The maximum score is 40 points and higher scores indicate more pronounced orthorexic behavior. A cutoff score of ≥ 30 indicates the presence of ON, while a score between 25 and 29 (95th percentiles) describes the risk of ON [9].

(b) The ORTO-15 [3] is a brief scale assessing orthorexia behaviors and attitudes that was initially developed and validated among Italian college students. It includes 3 subscales: cognitive aspects, clinical concerns, and emotional factors. It can be used as a total score reflecting global orthorexic tendencies with scores ranging from 15 to 60. A cutoff score of 40 was originally identified as reflecting the presence of ON. Alpha’s Cronbach in this study was 0.808.

Then, criterion validity was evaluated measuring other variables which has been demonstrated to be associated, or somehow overlapping, with ON [4, 5], such as eating disorders, depression, and obsessive–compulsive symptoms, using the following self-reported questionnaires.

(c) The Disordered Eating Questionnaire (DEQ) [22] is a 24-item scale assessing disordered eating-related behaviors and attitudes. This scale allows to calculate a valid and reliable global score of disordered eating-related behaviors (restrictive eating, binge eating and purging behaviors, willing to lose weight, ruminating, and worrying about weight and body shape, engaging in intense physical exercise to lose weight, etc.), which clinical cutoff score has been indicated as 30 [23]. Moreover, two items assessing participants’ height and weight allow us to calculate BMI (weight kg/ height m2). Cronbach’s α in the validation study was 0.90, while in this study was 0.933 indicating an excellent internal consistency.

(d) The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [24] is a 21-item self-report scale that assesses the presence and severity of affective, cognitive, and physical components of depression. The Italian version of the BDI-II showed excellent psychometric properties [25, 26]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.896 indicating a strong internal consistency.

(e) The Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) [27] in the Italian version of Sica and colleagues [28] is a widely used 18-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of obsessive and compulsive symptoms (washing, obsessing, hoarding, ordering, checking, and mental neutralizing). The Italian version of the OCI-R indicates good internal consistency and 30-day test–retest reliability (from 0.87 to 0.99) as well as good convergent, divergent, and simultaneous validity. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.892 indicating a strong internal consistency.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 23 and MPLUS 8.

All I-DOS items were examined for violations of normality. Specifically, according to Tabachnick and Fidell [29], absolute skewness and kurtosis values greater than |1| reflect normality deviations. Values of several items were above the recommended cutoffs, so the analyzed variables were not realistically normally distributed. Regarding missing values, the missing rates ranged from 1.9 to 3.3% and using Little’s MCAR test [30] we highlighted that the missing pattern was missing completely at random, χ2 = 39.335 (p > 0.05). Given this, in MPLUS, we used the full information maximum likelihood approach (FIML), which produces unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors under MAR and MCAR [31].

With the aim of testing the original latent structure of DOS [8], a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model positing one-factor was carried out. Specifically, I-DOS items have only four response options, and they are not normally distributed; therefore, we treated the data as ordinal (option “categorical” in Mplus). Accordingly, model parameters were estimated using the robust weighted least squares—means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator [32]. The following fit indices with respective recommended cutoff values [33] were reported: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; less than 0.08 indicates an acceptable fit) with associated confidence interval and with the test of close fit that examines the probability that the approximation error is low (p values > 0.05 indicates a good fit); Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; greater than 0.90 indicates an acceptable fit); Comparative Fit Index (CFI; greater than 0.90 indicates an acceptable fit); Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; less than 0.08 indicates an acceptable fit). In addition, chi-square statistics were also reported. However, chi-square results were not considered in interpreting model fit due to its sensitivity to large sample size [34].

In the next step, according with the Meredith’s framework [35], factorial invariance tests across gender were computed by means of a hierarchical series of multigroup CFAs. With the aim to examine the latent means differences, the following levels of measurements invariance were examined: configural (i.e., same number of factors and same loading patterns across groups), metric (i.e., factor loadings equal across groups) and scalar (i.e., equivalence of item intercepts). To compare these nested models fit, chi-square difference tests were computed. In addition, difference in CFI were calculated where an ΔCFI > 0.01 indicates a significant change in model fit [34]. To check the source of lack of equivalence, MPLUS modification indices were also investigated. In this regard, when a constraint is untenable, it can be relaxed to obtain partial invariance [36].

Afterwards, internal consistency of I-DOS was evaluated by calculating the Cronbach Alpha coefficient. According to Nunnally [37], a 0.70 or above Cronbach’s alpha indicates an acceptable value.

Moreover, with the aim of testing I-DOS criterion validity, Pearson’s correlations with the ORTO-15 total score, DEQ total score, OCI-R total score, and BDI-II sum score were calculated. In addition, association between DOS and BMI was also evaluated.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The sample consisted of 422 Italian students, 303 women (71.8%) and 119 men (28.2%). The mean age of participants was 20.70 years old (± 3.44), the minimum age was 18 years. The mean body mass index (BMI), based on the self-reported weight and height, was 21.83 (± 3.42). Participants who had a high school diploma were mainly represented in our sample (60.3%). Finally, only 46.3% of the sample performed physical activity, while 53.7% did not engage in any sport activity. Table 1 describes clinical variables scores evaluated in our sample (i.e., DOS, ORTO-15, DEQ, BDI-II, and OCI-R) by descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation.

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA with 415 participants was conducted for the one-factor model. Seven cases with missing values on all the measured items were not included in the analysis.

The CFA yielded ambiguous results: χ2(35) = 179.212, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.100, 90% CI = 0.085–0.114, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.970; TLI = 0.962; SRMR = 0.054). Specifically, RMSEA was widely above acceptable thresholds. Thus, we examined potential sources for this not acceptable model fit and found that two error covariance (item 6 and 10; item 4 and 7) had large and significant MI value. Both pairs of items have a similar meaning and measure similar aspect of the ON construct: in particular item 6 and 10 refer to the consequences of unhealthy eating, while item 4 and 7 refer to the social consequences of orthorexia nervosa. Accordingly, we re-ran a model with this two error covariances freely estimated. The revised model showed the following fit indices: χ2(33) = 112.565, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.076, 90% CI = 0.061–0.092, p = 0.003; CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.978; SRMR = 0.043.

Table 2 shows the standardized factor loadings that were all above 0.70. All the factor loadings resulted statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Tests of gender factorial invariance and of gender differences

According to the revised model, factorial invariance tests across gender were examined. Invariance results are shown in Table 3.

The first level (i.e., configural invariance) was achieved with the following fit indices: χ2(66) = 121.474, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.066, 90% CI = 0.046–0.081, p = 0.102; CFI = 0.990; TLI = 0.986; SRMR = 0.053.

When constraints on loadings were introduced, an inspection of the MI revealed that there were three constraints not tenable (factor loadings on item 7, item 1, and item 9). After they were relaxed, a partial metric invariance model was achieved (ΔCHI = 6.484, p > 0.05; ΔCFI = 0).

When scalar invariance model was tested, an examination of the MI revealed that introduced constraints were not tenable (thresholds of item 6, item 4, and item 10). These constraints were relaxed and a partial scalar invariance model was obtained (ΔCHI = 15.769, p > 0.05; ΔCFI = 0). Given all of the above, the latent means difference across gender was examined. To achieve this, mean value was constrained to zero for the male group (i.e., reference group), while in the female group was freely estimated. The results highlighted a nonsignificant difference (p > 0.05).

Validity and reliability

The reliability of the I-DOS, estimated by Cronbach’s α, was 0.888, showing a strong internal consistency. Moreover, all the items showed a moderate or high correlation with the total items ranged from 0.457 to 0.763 (Table 2).

The I-DOS total score had strong and statistically significant correlations with ORTO-15 total score (r = − 0.573; p < 0.001), where lower ORTO-15 score indicated higher levels of orthorexia tendencies and behaviors. Significant correlations were also found with disordered eating symptoms (DEQ total score, r = 0.597; p < 0.001), with obsessive and compulsive symptoms (OCI-R total score, r = 0.229; p < 0.001), and with the sum score of depressive symptoms (BDI-II total score, r = 0.262; p < 0.001). Regarding the association between BMI and orthorexic eating behavior (I-DOS total score), we found a statistically nonsignificant correlation (r = 0.079, p > 0.05).

Table 4 presents the correlations between the I-DOS and other constructs.

Distribution of an estimate of orthorexia nervosa in our sample

Participants mean score of the I-DOS was 15.60 (± 5.35), scores ranging from a minimum value of 10 and a maximum value of 37. Using the original version’s cutoff points [9], 3.2% of the study participants would be considered having ON (total score greater than 30), 4.9% would be at risk of ON (total score between 25 and 29), while no risk of ON was observed in 91.9% of the sample (total score less than 25).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the psychometric properties of the Italian translation of the DOS (I-DOS) in the Italian cultural setting. Besides, the study also explored construct validity by examining I-DOS total score correlations with different psychopathology indicators (i.e., depression, eating disorders, and obsessive and compulsive symptoms).

A CFA was performed to test the DOS’s unidimensional structure following the original creators of the questionnaire [9], with initial results revealing a questionable model fit. Subsequently, a significant improvement of the model fit was achieved after examining modification indices and an one-factor structure was observed, consistently with the previous results from the validation of DOS in other European cultures (e.g., Spain, Portugal) [15, 16]. More specifically, all fit indices of the model became acceptable after correlating error covariances of items 4 and 7 and of items 6 and 10. When examining item 4 (“I try to avoid getting invited over to friends for dinner if I know that they do not pay attention to healthy nutrition”) and 7 (“I have the feeling of being excluded by my friends and colleagues due to my strict nutrition rules''), one might discuss on the appropriateness of the language translation of these statements since no previous evidence in literature exists on high correlations between them. Nevertheless, in terms of their conceptual meaning, it may be recognized an intrinsically common theme concerning the social distress and isolation, which are crucial aspects of orthorexia assessed by the DOS [9, 13]. Regarding items 6 (“If I eat something I consider unhealthy, I feel really bad”) and 10 (“I feel upset after eating unhealthy foods”), both refer to negative feelings experienced as a consequence of eating foods considered unhealthy and previous authors [16] suggested to correlate their error covariances in order to improve the model fit. These findings are relevant insofar they explain the high correlations observed between these items and the decision to freely estimate their relative error covariance. Future studies would further explore the aforementioned item contents and eventually identify which item in the pair would be identified as conceptually redundant [38]. In this regard, in the present study, the high scale’s internal consistency (α = 0.888) and the moderated to high item-total correlations indicated robustness of the indicators.

However, in the final model obtained, different fit indices showed different acceptance levels. Specifically, SRMR, TLI and CFI were consistent with recommended cutoff values [33], whereas the RMSEA was above the cutoff. This discrepancy may depend on the fit indices used, as previous authors suggested [39]. More specifically, differently from CFI, the RMSEA is not influenced by the target-to-null models chi-square difference, but only by the target-model chi-square. When the difference among the target and the null model chi-squares is high and the target model chi-square is high, the CFI may evidence good fit, while the RMSEA does not [39]. This scenario seems to reflect the results of the present study, with the ratio of the null to target chi-square equal to 43.548, and the difference among the null and target chi-squares equal to 4789.424. Furthermore, RMSEA is also affected by model’s degrees of freedom (DFs), with DFs relatively small being associated with a larger RMSEA [39]. However, DFs of the final model were equal to 45, thus suggesting that low DFs may not be the origin of misfit, which is likely to depend on high chi-square values due to the larger sample size [39].

The results of the validity analyses revealed significant correlation coefficients between the total score of I-DOS and all the other measures included, except for BMI. First, the significant negative association found with ORTO-15, consistently with previous evidence [40], suggests a good convergent validity of the I-DOS as lower scores of ORTO-15 indicate high risk of ON [9]. On the other hand, results showed that I-DOS total score was positively related to overall eating disorder psychopathology (i.e., DEQ) as previous authors demonstrated [40]. These findings revealed that the construct of ON assessed by the I-DOS is not clearly distinguishable from the risk of eating disturbances as measured by the DEQ in the present sample. This lends support to research reporting significant relationships between orthorexic traits and levels of eating pathology [41, 42]. Generally, symptoms of ON and of eating disorders might be considerably overlapping, since healthy eating intentions and concerns about caloric intake are typically linked, especially for restrained eaters [43]. This association could be partially explained by the fact that individuals with orthorexic tendencies often report similarities with traditional eating disorders, such as the cognitive fixation on nutrition and the rigid reduction of foods considered dangerous for health or body image [44]. In addition, people with orthorexic traits were found to report a distorted perception and evaluation of their body [8], which has been regarded as a peculiar core symptom of eating disorders [2]. Overall, these findings suggest that although theoretically distinguishable, ON and eating disorders may be significantly related. Future studies are needed in order to establish more defining reliable and valid diagnostic criteria for ON.

The positive and significant correlation between I-DOS and overall depression symptomatology measured through the BDI-II found in the present study is consistent with the existing literature on the association between ON and depressive symptoms [45, 46]. Furthermore, this correlation was relatively low, thus supporting the discriminant validity of the I-DOS. Low, but significant correlation coefficient was also found between I-DOS and the severity of obsessive and compulsive symptoms measured by OCI-R total [25], consistently with the previous evidence [47]. This finding reveals that the two conditions may have similar cognitive and behavioral characteristics, as some authors suggest [48]. For example, individuals with ON spend most of their time in ritualistic behaviors and excessive efforts to select and prepare healthy food, similar to patients with obsessive and compulsive disorder (OCD) [49]. Moreover, ON is typically characterized by obsessions (e.g., overthinking about food preparation, inflated concern over contamination, and impurity) and impaired social functions like OCD [50]. These similarities between spectrum of symptoms of ON and of OCD have prompted debate as to whether orthorexia is a unique disorder or a subset of OCD [51]. Some authors suggest that the association between obsessive and compulsive tendencies and ON may reflect the high comorbidity between EDs and OCD instead to indicate ON as a disorder on the obsessive and compulsive spectrum [48]. Although further studies are needed to conclusively understand whether ON is a distinguishable pathological entity from obsessive and compulsive disease or not, we may be confident that ON is set of symptoms that are related, but distinguishable from OCD. In fact, the size of the correlation coefficients are small (according to Cohen’s categories); thus, suggesting that they are different but related constructs.

Finally, a nonsignificant association between I-DOS and BMI was observed in the present investigation. This result might indicate that ON is unrelated to weight, as previous studies demonstrated [16, 52].

In order to eventually estimate prevalence of ON assessed by the DOS, we used original cutoff points and obtained an ON prevalence of 3.2% and an ON-prevalence risk of 4.9% thus summing up to 8.1%. These results are similar to other reported in previous literature. In particular, some authors examining ON in adult samples reported comparable prevalence [53] and prevalence risk [54] percentages while others [46] found higher prevalence rates (e.g., 6.9%). These differences could be explained by the methodological approach of data collection used in the aforementioned studies. More specifically, Luck-Sikorski and colleagues [46] assessed orthorexic behaviors through a population-based telephone survey which is known to present biases related to social desirability [55]. As one of the strongest underlying motivations for ON is social desirability (i.e., being healthy to gain social support) [56], it could be hypothesized that participants of Luck-Sikorski and colleagues’ study might report exaggerated ON symptoms when interviewed by telephone, in order to appear compliant with healthy diet. Further studies are needed to examine whether different survey methods (i.e., online, offline, and telephone) for measuring ON could induce different pressure for socially desirable responding. Moreover, our prevalence percentages were estimated on the bases of German cutoff scores. Future studies should evaluate ON cases and noncases through independent instruments (e.g., a clinical evaluation) and compute cutoff scores appropriate for the Italian version of the DOS through ROC curves.

The current study clearly presents some limitations. First, its cross-sectional nature. Further studies are needed to more deeply examine the longitudinal validity of I-DOS (e.g., test–retest reliability). Second, the mere use of self-report questionnaires may be subject to social desirability effects and recall bias. Future studies should include measure of eating behavior and habits (e.g., food diary) [57] as well objective anthropometric measure and biomedical parameters. Third, the selection of nonclinical sample may limit the generalizability of our results. Future studies should evaluate the psychometric properties of the I-DOS scale in clinical samples (e.g., eating disorder or OCD patients). Finally, although our study is similar to most studies conducted in the Italian population, namely involving undergraduates and young adults, data regarding a wide age range are needed for exploring the prevalence of ON in specific stages of the life span.

Conclusions and clinical implications

The present study aimed at adapting the Italian version of the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (I-DOS) in a nonclinical sample of university students. This 10-items scale appears to be a valid and reliable measure to assess orthorexic behaviors and attitudes. The brevity of this scale and its good psychometric properties suggest that it could be a useful instrument in detecting or preventing orthorexia risk in nonclinical samples. Future studies should evaluate further psychometric characteristics and its potential use in clinical settings.

Our study gives also several suggestions regarding the construct of ON. Namely speculating about the clinical significance of the correlations coefficients between I-DOS orthorexia scores and scores on eating and obsessive disorders symptoms, consistently with an increasing amount of findings, we may hypothesize, that: (1) ON is an independent clinical entity; (2) it should be included within the eating disorders chapter of the DSM; (3) although sharing some similarities with obsessive–compulsive symptoms, it could be considered a related, but independent construct.

What is already known on this subject?

The Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS) is a reliable and valid instrument to assess orthorexia nervosa. It was adapted in different languages and its good psychometric properties confirmed.

What does this study add?

This study demonstrates that the Italian version of the DOS (the I-DOS) is a valid and reliable measure to assess orthorexic behaviors and attitudes in a nonclinical sample of university students. Its original unidimensional structure has been confirmed in the Italian version with acceptable or great fit indices and a strong internal consistency.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bratman S (1997) The health food eating disorder. Yoga J 42:50

Bratman S, Knight D (2000) Health food junkies: overcoming the obession with healthful eating. Broadway Books

Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C (2005) Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord 10(2):e28–e32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327537

Dunn TM, Bratman S (2016) On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav 21:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.006

Cena H, Barthels F, Cuzzolaro M, Bratman S, Brytek-Matera A, Dunn T, Varga M, Missbach B, Donini LM (2019) Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: a narrative review of the literature. Eat Weight Disord 24(2):209–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0606-y

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub

Meule A, Holzapfel C, Brandl B et al (2020) Measuring orthorexia nervosa: a comparison of four self-report questionnaires. Appetite 146:104512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104512

Gleaves DH, Graham EC, Ambwani S (2013) Measuring, “orthorexia”: development of the eating habits questionnaire. Int J Ed Psychol Assess 12(2):1–18

Barthels F, Meyer F, Pietrowsky R (2015) Die düsseldorfer orthorexie skala-konstruktion und evaluation eines fragebogens zur erfassung ortho-rektischen ernährungsverhaltens. Z Klin Psychol Psychother 44(2):97–105. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000310

Vainik U, Neseliler S, Konstabel K, Fellows LK, Dagher A (2015) Eating traits questionnaires as a continuum of a single concept. Uncontrol. Eating Appet. 90:229–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.004

Vainik U, Meule A (2018) Jangle fallacy epidemic in obesity research: a comment on Ruddock et al. (2017). Int J Obes 42(3):585–586. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.264

Rogoza R, Donini LM (2021) Introducing ORTO-R: a revision of ORTO-15: Based on the re-assessment of original data. Eat Weight Disord 26(3):887–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00924-5

Chard CA, Hilzendegen C, Barthels F, Stroebele-Benschop N (2019) Psychometric evaluation of the English version of the Düsseldorf Orthorexie Scale (DOS) and the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among a US student sample. Eat Weight Disord 24(2):275–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0570-6

He J, Ma H, Barthels F, Fan X (2019) Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale: prevalence and demographic correlates of orthorexia nervosa among Chinese university students. Eat Weight Disord 24(3):453–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00656-1

Parra-Fernández ML, Onieva-Zafra MD, Fernández-Muñoz JJ, Fernández-Martínez E (2019) Adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the DOS questionnaire for the detection of orthorexic nervosa behavior. PLoS ONE 14(5):e0216583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216583

Ferreira C, Coimbra M (2020) To further understand orthorexia nervosa: DOS validity for the Portuguese population and its relationship with psychological indicators, sex, BMI and dietary pattern. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01058-4

Brytek-Matera A (2020) The Polish version of the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (PL-DOS) and its comparison with the English version of the DOS (E-DOS). Eat Weight Disord 26(4):1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01025-z

Lasson C, Barthels F, Raynal P (2021) Psychometric evaluation of the French version of the Düsseldorfer Orthorexia Skala (DOS) and prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among university students. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01123-6

Campbell D, Brislin R, Stewart V, Werner O (1970) Back-translation and other translation techniques in cross-cultural research. Intern J Psychol 30:681–692

Hambleton RK (1994) Guidelines for adapting educational and psychological tests: A progress report. Eur J Psychol Assess 10:229–244

Schaffer BS, Riordan CM (2003) A review of cross-cultural methodologies for organizational research: a best-practices approach. Org Res Methods 6:169–215

Lombardo C, Russo PM, Lucidi F, Iani L, Violani C (2004) Internal consistency, convergent validity and reliability of a brief questionnaire on disordered eating (DEQ). Eat Weight Disord 9(2):91–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325051

Lombardo C, Cuzzolaro M, Vetrone G, Mallia L, Violani C (2011) Concurrent validity of the Disordered Eating Questionnaire (DEQ) with the eating disorder examination (EDE) clinical interview in clinical and non clinical samples. Eat Weight Disord 16(3):e188-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325131

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) BDI-II, Beck depression inventory: manual. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX

Ghisi M, Flebus GB, Montano A, Sanavio E, Sica C (2006) Beck depression inventory-second edition. Manuale. Organizzazioni Speciali, Adattamento Italiano, Firenze

Sica C, Ghisi M (2007) The Italian versions of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Psychometric properties and discriminant power. In: Sica C, Ghisi M (eds) Leading-Edge Psychological Tests and Testing Research. Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp 27–50

Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S et al (2002) The obsessive-compulsive inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess 14(4):485–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485

Sica C, Ghisi M, Altoè G et al (2009) The Italian version of the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory: its psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. J Anx Disord 23(2):204–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.001

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using multivariate statistics. Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, New York

Little RJA (1988) A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 83(404):1198–1202

Enders CK, Bandalos DL (2001) The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling 8(3):430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Muthen B, Asparouhov T (2002) Latent variable analysis with categorical outcomes: multiple-group and growth modeling In Mplus. Mplus Web Notes. 4(5):22–23

Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J (2006) Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res 99(6):323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB (2002) Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model 9(2):233–255

Meredith W (1993) Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika 58(4):525–543

Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthén B (1989) Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol Bull 105(3):456

Nunnally JC (1978) Psychometric theory, 2d edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Abramowitz JS, Huppert J, Cohen AB, Tolin DF, Cahill SP (2002) Religious obsessions and compulsions in a non-clinical sample: the Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS). Behav Res Ther 40(7):825–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00070-5

Pezzuti L, Barbaranelli C, Orsini A (2012) Structure of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised in the Italian normal standardisation sample. J Cogn Psych 24(2):229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2011.62978

Parra-Fernández ML, Onieva-Zafra MD, Fernández-Martínez E, Abreu-Sánchez A, Fernández-Muñoz JJ (2019) Assessing the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in a sample of university students using two different self-report measures. Int J Environ Res Publ Heal 16(14):2459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142459

McInerney-Ernst EM (2011) Orthorexia nervosa: real construct or newest social trend? Doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri, Kansas City. https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/handle/10355/11200. Accessed 2 Jan 2021

Griffiths S, Hay P, Mitchison D et al (2016) Sex differences in the relationships between body dissatisfaction, quality of life and psychological distress. Aust NZ J Publ Heal 40(6):518–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12538

Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM, Essayli JH (2019) Disentangling orthorexia nervosa from healthy eating and other eating disorder symptoms: relationships with clinical impairment, comorbidity, and self-reported food choices. Appetite 134:40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.12.006

Barthels F, Meyer F, Huber T, Pietrowsky R (2017) Orthorexic eating behaviour as a coping strategy in patients with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 22(2):269–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0329-x

Barrada JR, Roncero M (2018) Bidimensional structure of the orthorexia: development and initial validation of a new instrument. An Psicol 34(2):283–291. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.34.2.299671

Luck-Sikorski C, Jung F, Schlosser K, Riedel-Heller SG (2019) Is orthorexic behavior common in the general public? A large representative study in Germany. Eat Weight Disord 24(2):267–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0502-5

Brytek-Matera A, Staniszewska A, Hallit S (2020) Identifying the profile of orthorexic behavior and “normal” eating behavior with cluster analysis: a cross-sectional study among polish adults. Nutrients 12(11):3490. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113490

Altman SE, Shankman SA (2009) What is the association between obsessive–compulsive disorder and eating disorders? Clin Psychol Rev 29(7):638–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.001

Yilmaz H et al (2020) Association of orthorexic tendencies with obsessive-compulsive symptoms, eating attitudes and exercise. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 16:3035–3044. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S280047

Brytek-Matera A, Fonte ML, Poggiogalle E, Donini LM, Cena H (2017) Orthorexia nervosa: relationship with obsessive-compulsive symptoms, disordered eating patterns and body uneasiness among Italian university students. Eat Weight Disord 22(4):609–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0427-4

Koven NS, Abry AW (2015) The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:385–394. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S61665

Oberle CD, Lipschuetz SL (2018) Orthorexia symptoms correlate with perceived muscularity and body fat, not BMI. Eat Weight Disord 23(3):363–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0508-z

Depa J, Schweizer J, Bekers SK, Hilzendegen C, Stroebele-Benschop N (2017) Prevalence and predictors of orthorexia nervosa among German students using the 21-item-DOS. Eat Weight Disord 22(1):193–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0334-0

Strahler J, Haddad C, Salameh P, Sacre H, Obeid S, Hallit S (2020) Cross-cultural differences in orthorexic eating behaviors: Associations with personality traits. Nutrition 77:110811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2020.110811

Kreuter F, Presser S, Tourangeau R (2008) Social desirability bias in CATI, IVR, and web surveys: the effects of mode and question sensitivity. Public Opin Q 72(5):847–865. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn063

Kiss-Leizer M, Tóth-Király I, Rigó A (2019) How the obsession to eat healthy food meets with the willingness to do sports: the motivational background of orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 24(3):465–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00642-7

Howat PM, Mohan R, Champagne C, Monlezun C, Wozniak P, Bray GA (1994) Validity and reliability of reported dietary intake data. J Am Diet Assoc 94(2):169–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8223(94)90242-9

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This study did not receive specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC and CL projected the study; SC and MV collected the data. AZ, CB and SC analyzed the data. SC, MV and AZ wrote the first draft with contributions from the other authors. All authors reviewed and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript. CL supervised the entire process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cerolini, S., Vacca, M., Zagaria, A. et al. Italian adaptation of the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (I-DOS): psychometric properties and prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among an Italian sample. Eat Weight Disord 27, 1405–1413 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01278-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01278-2