Abstract

Introduction

Despite a higher prevalence of mental disorders and poorer outcomes, ethnic minorities have low participation in mental health research in the UK. This restricts the generalisability of results and leads to health inequalities. It is important to identify barriers to recruitment and develop strategies to overcome them.

Methods

Field researchers recruiting on the Northwest site of the CRIMSON trial kept research diaries on the recruitment process of the South Asians. Challenges in recruiting them were reflected on by researchers, and effective strategies employed were documented. Diary entries were kept for all participants and those who refused. Thematic analysis was carried out on the diary accounts and common themes documented.

Results

There were 46 South Asian servicer users eligible to trial participation. Field researchers were able to approach 32 (70 %) service users and out of these 23 (50 %) were recruited. From these 23 recruited participants, 13 were deemed to have cultural issues requiring researchers to devise strategies beyond the standard recruitment procedures, remaining 10 did not present with any cultural issues. Diary entries for the 13 participants with cultural issues and 9 that refused to participate were available. Thematic analysis resulted in 12 themes with provision of translated materials, availability of interpreters and family involvement emerging as the main themes.

Conclusions

The identified barriers and solutions can be used in designing future research. Staff training and strategies can be planned in advance thus pre-empting recruitment shortfalls. This will enhance ethnic participation and help bring down ethnic health disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well established that despite a higher prevalence of mental disorders [1–7], ethnic minorities tend to have low participation rates in mental health research in the UK [8]. Some have suggested that this is “due to perceived cultural and communication difficulties” [9], citing the difficulties with language and literacy problems throughout the recruitment stage; particularly when gaining informed consent. Others have referred to the increased costs of recruiting from ethnic minorities [10], which are often not considered in research proposals.

Cultural and communication barriers are cited throughout the literature as impediments to recruitment. A systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of ethnic minorities into mental health trials [11] described cultural barriers as lack of recognition and insight into illness, poor help-seeking, stigma and participants’ lack of understanding with regard to the benefits of research. Communication barriers included non-availability of translated materials and linguistically matched recruiters. Both categories to an extent are closely linked, but we need to fully understand them as both require different solutions. Such barriers are not only problematic when recruiting ethnic minority groups into mental health research, but are also relevant within research of non-mental health conditions [12–18].

There are two key reasons why researchers should make particular efforts to recruit participants from ethnic minorities. First, under-representation of sub-groups from the general population compromises the generalisability of the study findings. Second, reduced participation in research denies people from ethnic minorities access to new treatments, and promulgates health inequalities [12, 19, 20]. There are few UK-based mental health trials that have made particular efforts to recruit people from ethnic minorities [21, 22] and the situation is similar in the USA. Non-mental health trials have revealed effective recruitment of ethnic minorities [15, 16, 18].

Recruiters’ experiences, both internationally and at a local level, add to the knowledge base within this area, providing valuable lessons for future research involving ethnic minorities. Critical consideration of the recruitment of diverse minority groups in the US [23] was undertaken in order to understand cultural distinctions within research into ageing, which supports the need to consider cultural barriers, such as those categorised above. Other research exploring the diverse ethnic minority recruitment in the USA placed importance on recruitment rates, considering how women can be more successfully recruited into non-mental health studies [24]. Such research provides descriptive analysis of recruitment rather than in depth accounts from front line researchers.

Within the UK, some attempts have been made to describe researchers’ experiences of recruiting South Asian participants into non-mental health research. A review of the literature regarding recruitment into clinical trials and qualitative interviews (from both professionals and participants) has suggested some effective strategies for recruiting South Asians into clinical trials [25]. Recruitment strategies within diabetes and obesity research [16] have added to the knowledge base of recruiting South Asians, with authors documenting their findings from questionnaires completed by recruiters [15]. Whilst these studies introduce the recruiters’ perspectives, they draw on quantitative data, rather than elaborating on the qualitative findings from front line researchers’ recruitment experiences. Evidence of more qualitative experiences are reported within the recruitment of British South Asians during a cancer clinical trial [18], which uses insights from literature and local experiences of front line staff to review the factors that may influence the participation of this group. Whilst this literature details the importance of considering the recruitment of ethnic minorities into research, the authors did not find any literature pertaining to the experiences of recruitment within mental health research in the UK. Instead the learning comes from physical health trials. Therefore, this paper seeks to build on what is already known in order to explore researchers’ experiences of the recruitment of South Asian participants into mental health research.

The UK has an ethnic minority population of 8 % of whom 50 % [26] are South Asian (defined as family origin in India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives). In the UK, South Asians have a disproportionately high prevalence of mental disorders [4, 21]. Successful studies focusing on mental health in South Asians have put considerable targeted effort into developing productive relationships with participant communities [27, 28].

The whole process of research participation needs to be examined in relation to South Asian communities to identify barriers to recruitment in order to develop facilitated information for potential subjects and training for staff. Recruitment is generally undertaken by field researchers, who are therefore well-placed to characterise the difficulties in accessing hard-to-reach groups. It is essential to train staff to equip them with the skills to sensitively approach participants and develop effective working relationships with them. New recruitment strategies like this will facilitate the recruitment of South Asian participants into research, with potential benefit to themselves and others.

We describe here a thematic analysis of diaries on the recruitment of South Asians kept by field staff on the CRIMSON [29] trial, a multi-centre RCT of Joint Crisis Plans. The CRIMSON trial aimed to recruit participants from ethnic minorities as they have been shown to have disproportionately higher admission rates under the Mental Health Act than white service users [30–34]. The trial was designed to be inclusive for ethnic minorities and arrangements were made to facilitate their recruitment with particular reference to South Asians and Afro-Caribbeans. The study’s aim is to describe the experiences of research staff in recruiting South Asians into the trial as they have historically been under represented in clinical research, often due to problems in recruitment.

CRIMSON had three recruitment sites—London, Birmingham and Manchester/East Lancashire. In this paper, we report findings from the Manchester/East Lancashire site, which has a significant South Asian population, mainly from India and Pakistan (Greater Manchester, 3.8 %; Burnley, 7.15 %; Blackburn, 20.6 %) [26]. The challenges and culturally sensitive strategies used to recruit these participants within the Manchester/East Lancashire site were explored by the field researchers. In addition, contact made with those people who refused to participate has been documented, with accounts as to the reasons for refusal provided.

Methodology

The CRIMSON [29] trial was an RCT investigating the effectiveness of Joint Crisis Plans in reducing compulsory psychiatric hospital admissions and received ethical approval from King’s College Hospital Research Ethics Committee. A Joint Crisis Plan is a document that contains service users’ preferences about treatment and practical provisions that they would wish to have in the event of a future crisis. This collaborative planning approach includes the views of both the service user and their clinical treatment team. The plan was developed through a facilitation process by an independent clinician who ensured that the service users’ views were heard whilst also confirming that the care team were in agreement. The aim was that the process of devising a Joint Crisis Plan would empower service users, facilitate early detection and treatment of relapse and mental illness and decrease the use of the Mental Health Act. Participants were recruited from community mental health teams, assertive outreach teams and early intervention teams, and they required a diagnosis of a psychotic illness; this included schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and psychotic depression.

The methods of recruitment into CRIMSON followed three stages. The eligibility criteria were checked. Eligible service users were aged 16–65, had a diagnosis of psychosis, were on enhanced-level care programme approach and had a hospital admission in the previous 2 years. Once it was determined that the criteria were met, the field researchers approached these service users’ care coordinators for their approval and to discuss the best method of approaching the service user. Service users were then contacted by the method considered most appropriate, including post, telephone or home visits, which could be joint visits with care coordinators or other support staff.

As one of the primary aims of the trial was to have an ethnically representative sample, the trial used information sheets, consent forms and questionnaires translated into Urdu and Gujarati, and interpretation was available in both languages. In addition, the Urdu-speaking local investigator (WW) was also available to speak to families. All interviews were conducted in the home of either the participant or a relative.

Based on previous experience in community-based data collection, the team anticipated some barriers to recruitment of South Asians and decided to keep diaries detailing accounts of the recruitment process for all South Asians approached (excluding those with very fluent English, e.g. as first/only language) noting the dynamics of the recruitment process where possible. This allowed researchers to record the subtleties in difference between the recruitment processes for South Asian participants, compared with the recruitment of white British participants. Therefore, whilst it was the intention of researchers to complete diaries for all South Asians at the outset, entries on a number of participants were not deemed necessary, as no such differences in the recruitment process were observed. To clarify, diary entries were made for only those South Asian service users where there was a need to consider cultural issues in the recruitment process. In this case, cultural issues were defined as issues that required researchers to go above and beyond the standard recruitment procedures for the trial. Ethnic minority participants who did not have any language barriers to recruitment or need any additional strategies to be employed to assist their recruitment were classified as having ‘no cultural issues’.

The diaries were maintained by field researchers (AWh and GB) and interpreters (AW, Urdu and DM, Gujarati). No specific boundaries were imposed on what researchers could include within their diaries, beyond their own assessment of which strategies were necessary above the standard recruitment procedures. In addition to these strategies, the principal investigator (WW) was able to offer support to the field researchers and converse with participants over the telephone and in person to assist the recruitment process. The details of the research team are provided in Table 1. These diaries were completed with an aim to use them for furthering the team’s knowledge and developing future training. Diaries were kept within the recruitment process for both consenting and non-consenting participants. Ethical approval was received for reporting data from service users who did not participate (where this information was available to the research team).

The purpose was to provide qualitative data for subsequent thematic analysis. In the analysis of the diaries, a thematic analysis method was used to analyse the transcribed data following a systematic, iterative process, whereby codes were applied to the transcripts, and further refined and organised into categories that represented the main themes arising from the data [35]. Initially, themes contained in the diaries were identified by AW/WW, who devised codes which were grouped and refined for analysis, in order to identify the ‘story’ behind each theme and how it fitted into the broader ‘overall’ story—i.e. how researchers overcame the barriers to recruitment of South Asians into the CRIMSON study. Subsequently, new codes were added where the initial categorisation proved inadequate to reflect participants’ experiences. Findings were discussed periodically within the research team to refine, challenge and clarify the emerging conceptual understanding of the participants’ recruitment experiences. Once the analysis was completed, the themes were read by all contributors and additional comments incorporated.

Results

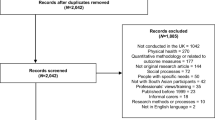

These diaries reflect on the recruitment process of South Asian participants into the CRIMSON trial at the Manchester/Lancashire site. In total, 46 South Asian service users were screened to be eligible and all were approached, either by the researcher or care coordinator. From these participants, 50 % (n = 23) were successfully recruited (as illustrated below). In comparison, 276 White British patients were screened to be eligible, with 51 % (n = 142) being successfully recruited into the study. Ninety-nine of these people refused to participate, either directly with the researchers or through their care coordinator and 35 were not approached, due to their mental health at the time. Figure 1 shows the number of South Asian participants who were recruited from the Lancashire/Manchester site and the number that were included in the diary accounts by field researchers (as described earlier within the ‘Methodology’ section).

A breakdown of the ethnicity of the participants is tabulated below in Table 2, showing a comparison between those that presented cultural issues for consideration against those that did not.

The 13 South Asian participants that did not require additional cultural considerations during the process were recruited smoothly, meaning that diary entries for their recruitment did not warrant inclusion. The remaining 10 participants that were recruited, along with the 9 people that were approached but refused, are referred to in the following diary extracts, taken from field researchers’ experiences of the recruitment process.

Thematic Analysis

The themes were initially organised in the sequence that they were encountered during the process of recruitment, hence in chronological order as to when the barriers were met. The analysis then developed to consider grouping the individual themes into the type of barrier documented. Three broader themes emerged from discussions within the research team and the individual barriers are presented within the three umbrella categories—barriers that can be overcome without any extra effort, resource-based barriers and training needs barriers. To clarify further, those barriers that can be overcome without any extra effort should be resolved through routine good practice. Resource-based barriers refer to material resources and often require additional financial consideration in order to implement effectively. The third category of training needs barriers, groups those barriers which can be overcome through providing effective training to research staff and those clinical staff who will be actively involved in research processes. Within each of the three broader themes, the individual barriers remain presented in chronological order of the research process.

The analysis from the diary entries produced 12 themes which are explored below, within the three broader categories as previously explained. The quotes provided are taken directly from the field researcher diary entries and details are given after each quote of the participants to which the communication refers to.

-

1.

Barriers Which Can Be Overcome Without Any Extra Efforts

-

Number of Visits

The recruitment of South Asian participants into the CRIMSON trial often required numerous visits; one participant (NA, 31 years old, UK-born Pakistani female) was visited three times and it took six separate visits to recruit another participant (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male). The range of visits to successfully recruit the 23 South Asian participants into the study was one to six with the mean being 1.74. The recruitment of White British participants took less visits with the number of visits needed not exceeding two. The range for the recruitment of this group was one to two, with the mean being 1.10.

-

Care Coordinator Involvement

Because of the structure of mental health services and the way the trial was designed, care coordinator involvement was crucial for recruitment as they act as gatekeepers to the researchers opening communication with the service users. Their role served various functions, from conducting a joint visit with them or providing their support in discussing and encouraging recruitment. On occasions, the care coordinator was instrumental in actually arranging the appointment where the trial would be discussed.

It was agreed that the participant would discuss this in the near future with their care coordinator who would consequently contact me with the information. (MI, 55 years old, Pakistani-born male)

The role of the care coordinator varied depending on whether they could speak the potential participant’s first language. In some cases, an English-only-speaking care coordinator would be limited to providing an introduction to the researchers. On other occasions, multi-lingual care coordinators were able to actively promote the research in the participant’s first language.

My first contact with her was a joint visit with her English-only-speaking care-co-ordinator. (GB, 36 years old, Bangladeshi-born female)

At my first visit to this woman I was accompanied by the Urdu-speaking care-co-ordinator. (RK, 29 years old, Pakistani-born female)

I visited the service user with their care coordinator and an interpreter who could assist with asking the questions in Gujarati. (AB, 42 years old, UK-born Indian female)

-

Timing of Appointments

The time that the recruitment appointments took place impacted on the consenting process. It was important to select the most convenient time with the participant, whilst also showing flexibility amongst pre-arranged appointments with their care coordinator.

Unfortunately this was at a rather stressful time for the family (school holidays) and care coordinator (the appointment had been delayed over an hour due to a crisis with another service user). The care coordinator had not informed the service user of the delay, but was nonetheless welcomed. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

At this appointment the service user was visibly very tired indeed and it was clearly an inappropriate time to seek informed consent for research. His wife said that they had relatives visiting and had all been up very late the night before. She told me that this happens quite a lot, and I had the impression that they found it overbearing, but had to go along with it for fear of offending family. School holidays were again due, so we agreed to leave it for the present. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

An interpreter describes how the timing of the appointment needed to be changed during their initial visit.

When she eventually came for the interview she could not get on with the interview as there was a lot of interference from her father in law. She was asked to leave the interview and make breakfast for him. Additionally she seemed ill at ease and a bit flustered hence we decided to re arrange the interview for another day. (RK, 29 years old, Pakistani-born female)

Throughout the recruitment process, it was not unusual for appointments to be cancelled at short notice or for participants not to be at home at the arranged time. This required persistence and flexibility from the researchers.

I was able to make an appointment to visit them on my own. However, they weren’t in and his wife later telephoned to apologise and re-set the appointment. As she has good English, she had had to accompany a non-English-speaking relative to a hospital appointment, which she has to do for a number of people. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

The interpreter’s child was ill, so she had to cancel the appointment. I explained this to the service user’s wife and arranged another date. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

Rapport with Participants

The rapport that both the researchers and interpreters built up with the participants over the initial meetings with them was a key factor in whether they were successfully recruited into the study or not.

The interpreter asked the majority of the questions and this really helped engage the service user, as they also spoke a lot about more general things that appeared to build up trust from them. (AB, 42 years old, UK-born Indian female)

It was clear that the service user’s wife and the interpreter had immediate rapport on the topic of concern over young children’s health, which made the atmosphere very pleasant. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

Opportunity to Communicate with Senior Research Staff

During the recruitment process, the researchers received assistance from an Urdu-speaking male psychiatrist (WW) who was a senior member of the research team. On two separate occasions, he was able to telephone the participant (or participant’s family) and make the initial contact. Making this initial contact in Urdu helped build rapport and made it easier to assess the willingness of the participant to become further involved in the recruitment process.

I never received an answer from the uncle, but the new care coordinator had no objection to him being approached directly in Urdu. A male Urdu-speaking doctor telephoned him and he quickly gave his permission for the service user to participate, and passed the phone to her and an appointment was made for myself and the interpreter to visit the following week, which we did, successfully. (RK, 29 years old, Pakistani-born female)

There was one occasion where the doctor accompanied a researcher on the consent visit. The presence of a doctor was appreciated by the participant and the other function this visit served was having a professional explaining the study to them in Urdu.

I asked if I might visit with an Urdu-speaking doctor (male). This visit was extremely successful. The conversation was mostly, but not wholly in Urdu and the tone very cordial. The outcome was that the service user agreed to be assessed for the study and we arranged an appointment with the interpreter. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

-

2.

Resource-Based Barriers

-

Availability of Bilingual Information

The research team ensured that all study materials were translated into Urdu and Gujarati so as to avoid exclusion on the basis of limited English-language skills. This included information sheets, consent forms, baseline assessments and intervention materials. Such information sheets were offered to all potential participants for whom Urdu or Gujarati was their first language. Depending on the individual concerned and advice from their care coordinator, information sheets were either posted out first or delivered in person and information sheets were also sent out to their families or key workers where appropriate.

As the service user's first language is Gujarati, an information sheet was posted out to her in Gujarati with an accompanying note saying that someone would be in contact soon. (AW, 53 years old, African-born Indian female)

The participant information sheet was left in both the English and the Urdu version. (MI, 55 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

Need for Multilingual Staff/Interpreters

-

Urdu

Five participants that were recruited required the presence of an interpreter so that consent and baseline information could be obtained in Urdu. On occasions, the allocated care coordinator was involved in assisting the consent process by interpreting the study information and facilitating a meeting with the participant and researchers.

This participant’s first language is Urdu so on the first visit I went along with their care coordinator who was able to translate the study information for them to help them make a decision about whether they would like to hear more about it. (MI, 55 years old, Pakistani-born male)

On one instance, the care coordinator always planned their regular visits alongside an interpreter and they were instrumental in setting up an appointment with the researcher.

The care co-ordinator arranged her appointments by visiting with an interpreter and setting a date for the next visit before leaving the house. We arranged to offer the service user a provisional date for myself and our interpreter to visit in the same way, which was successful. (AB, 51 years old, Pakistani-born female)

The recruitment process highlighted the necessity of researchers to check the language skills of participants. One participant’s first language was Bengali and whilst it was thought that a Bengali interpreter would be necessary, initial contact with an Urdu-speaking senior researcher showed that the participant’s Urdu skills were adequate to complete the assessment. This particular assessment required flexibility from the researcher as they explain:

The discussion included her husband, who did not have Urdu fluency, was in all three languages, with the service-user interpreting her husband’s Bengali into Urdu for the interpreter to convey to me. (GB, 36 years old, Bangladeshi-born female)

On occasion, family members assisted the translation process:

His wife knew how to speak English. All the same it was important that he understood what was going on so I translated for him in Urdu. My problem with this interview was that mostly his wife answered for him and on some questions she would answer even before I had a chance to translate it for him, however I am confident that we got accurate answers. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

Gujarati

Two participants required a Gujarati interpreter throughout the recruitment process. One of these was a member of the Community Mental Health Team, who was not directly involved in the service user’s care. The second was a clinical studies officer who worked as part of the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), a government funded network to support and coordinate research. The input from these professionals was invaluable in recruiting these participants.

During the consenting visit it was really useful to have the CSO [Clinical Studies Officer] there as their care coordinator reports that they don’t usually take an interpreter on their standard visits which can lead to limited communication. (AW, 53 years old, African-born Indian female)

The presence of an interpreter when this has previously been lacking in the service user’s treatment was found to be a beneficial effect on the participants clinical care as accounted for by the observations below. In this instance, the care coordinator had previously told the researcher that they did not know what language the service user spoke

The participant also said that they really felt listened to by having someone converse with them in their first language; so much so that they shed tears as they felt someone understood them. The CSO called the service user in a few days time and they said that they would like to take part, so the baseline assessment date was set up. The service user once again commented on how good it was to speak openly with the CSO as they felt understood and that someone was really listening to them. (AW, 53 years old, African-born Indian female)

The interpreter reports their experiences of the aforementioned visit highlighting the value of them being present from their perspective:

The husband sat in majority of the visit, conversing at times about his wife’s illness. They were both very respectful and seemed very pleased to have someone that spoke their language. She was very happy to speak to someone that was listening to what she had to say and at one point she did start to cry and reassurance was given. She seemed very confused and unclear about her treatment and in general about her mental health illness. The impression I got from the two visits with this person was that she lacked knowledge about the mental health service, what they provided her and whom she should contact. For example, one of the questions she repeatedly asked me was ‘why do they keep giving me the injection? It makes me very ill and I want to stop it’. Hence it appeared she had no understanding/education around the depot injection.

Also she kept referring me to as ‘bhati’ which means daughter in English, rather than my name, in Gujarati this is used in the community for the elderly to name the younger females. In addition to this she kept saying in Gujarati, directing at me that us Indians know what it is like in the ethnic community and being around a big nuclear family, having a busy household. (AW, 53 years old, African-born Indian female)

On one occasion, an interpreter assisted the researcher in explaining the trial to the potential participant over the phone prior to the visit. The presence of an interpreter and a conversation with a male Urdu-speaking doctor did not affect the service user’s decision to refuse participation. They were clear that they did not want to attend meetings with people that were not already involved in their care. The researcher’s account describes the recruitment attempts.

This man’s care co-ordinator told me that his first language is Pashtu, but that he also has some Urdu and English. In order to test whether the Urdu was sufficient for assessment, an Urdu-speaking male doctor arranged an appointment by telephone in Urdu for myself and the interpreter to visit to explain the study further. At the house, we met him and his married sister whose family he lives with. We spoke in English throughout as both were fluent and explained the study. Neither the service user nor his sister wanted to become involved in research. (HK, 31 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

-

-

3.

Training Needs Barriers

-

Awareness of Religious Obligations and Festivities

The timing of appointments, as explored above needs to be considered not only in terms of timings of the day or fitting around other appointments, but in terms of religious obligations. This cultural sensitivity was shown in the recruitment of one participant as explained below.

Upon arriving at the participant’s house the care coordinator noticed that the participant looked extremely tired and his behaviour indicated limited concentration. The participant explained that he was currently fasting for Ramadan and had been up very late the previous night worshipping. I made a joint decision with the care coordinator that I would provide a very brief amount of information about the research and then if they were interested in hearing more about it then I would arrange to come and visit again after Eid. The participant was able to concentrate enough to take in the research summary information and was very eager for me to visit again and so suggested a date the following week. (EP, 36 years old, UK-born Indian male)

-

Family Involvement

The most frequent issue that arose from recruitment of South Asian participants was the necessity to include family members in visits and in the decision as to whether participation was right for them. Within South Asian culture, the family has a greater influence on decision making than it does within white British households. Regardless of researchers’ own culture, it is important that all staff is aware of the extent of this influence and therefore this obstacle has been situated within the umbrella theme of a training needs barrier. During the recruitment process, family involvement often resulted in participants requiring numerous visits, as highlighted later in the diary extracts and the flexibility of researchers in providing sufficient time to allow that decision to be made.

On the first visit the participant was very interested in the study and asked if I could also talk through the information with their sister, stating that they would like to discuss it as a family after I had gone. I arranged to contact the participant again by phone and another appointment was arranged, where this time I met their father and brother. (NA, 31 years old, UK-born Pakistani female)

In addition to the requirement of general family involvement in recruiting participants, it was observed that with female participants it was necessary to involve male family members; usually their husband, father, father in law, or uncle. This involvement could develop trust between the family and the researcher and was often crucial in the participants obtaining permission from this person to take part.

On the first visit the female was in the house alone and was concerned that their husband was not in, so after a discussion it was decided that it may be helpful if she called her sister that lived across the street from her. On the second visit the participant had previously discussed the study with their family and they ensured that their husband was in the house. I was formally introduced to their husband and the participant said they felt it important for me to sit with him and get to know him before we began the interview. For this participant an important factor in her decision to participate was whether her husband trusted me and agreed to her participating or not. Therefore additional time was needed to build up this relationship prior to commencing the baseline interview. (NA, 30 years old, UK-born Pakistani female)

Service user’s husband and son advised them to take part and whilst they fully understood the study and gave informed consent, without the approval from their family, it would have been far more difficult to engage her. (AB, 42 years old, UK-born Indian female)

She said that she would need to ask her uncle for permission. (RK, 29 years old, Pakistani-born female)

Family involvement in recruitment was also shown to be useful in terms of the family having insight into the service user’s illness. This was helpful in relation to the research as they could highlight the specific benefits that involvement in the research could have for the individual.

The service user was rather preoccupied with other problems and was not really interested in the study, but his wife was extremely interested because she saw the potential value of the intervention in helping her manage her husband’s crises. We agreed that I would contact them again in several months time. (NM, 29 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

Understandable Explanations of Study

The explanation of the study and the researchers’ ability to describe processes in culturally sensitive terms was important in obtaining informed consent from the participants.

A long time was spent with the family exploring what the potential benefits of being involved in the trial may be and I frequently reiterated the importance of anonymity and confidentiality within the study. (AB, 42 years old, UK-born Indian female)

It was found to not only be general study terms that require clarity in their explanations, but the awareness of specific word meanings and how they could be misinterpreted, as explained below.

The service user remembered my visit with her previous care coordinator and said that she had misunderstood what was involved for her. She thought that because the project was described as a study, that she would have to go to college, which she didn’t want to do. (RK, 29 years old, Pakistani-born female)

The clinical and research terminologies used by researchers and their explanations of confidentiality could alleviate most participants’ concerns. However, at times, particularly in case of accessing medical case notes participants’ suspicions could not overcome.

I spoke with the service user on the phone. They wouldn’t allow their medical documents to be accessed under any circumstances and did not want any involvement in 18 months time for the follow up period. (DB, 44 years old, UK-born Pakistani male).

-

Service Users Did Not Think that the Research Could Benefit Them

Following communication between the researchers and service users with regards to the trial, five South Asian service users refused their participation in the trial on the grounds that they did not feel that it could benefit them.

I spoke with the service user several times on the phone and posted out information. They recognised it sounded interesting but said ‘it's not for me’. They said they want to look forward and forget the past; they do not want to talk about their illness and wants to move on with their life, (IA, 31 years old, UK-born Pakistani male)

Other reasons for service users not valuing the potential benefits that the research may offer them relate to insight into their illness or to the service user putting greater priority on addressing their current treatment.

She doesn’t want to take part because she states that she doesn’t have mental health problems anymore. (HP, 37 years old, UK-born Indian female)

I visited the service user, who refused and didn’t see the benefits. He is more concerned with changing his medication. (HA, 34 years old, UK-born Pakistani male)

An interpreter described one of their experiences where family were involved in relaying the potential participant’s views:

We never really had the chance to interview him because when we sat down for the interview his sister who could speak fluent English came and said that he doesn’t want to be involved in any interviews as he already has a lot to do and does not want to take on anymore involvement in any kind of interviews. (HK, 31 years old, Pakistani-born male)

-

Participant Did Not Attend Appointments Because They Did Not Feel They Could Say No

On two separate occasions, initial contact was made by the researchers to the service users and they engaged well in conversation and presented as being very interested in hearing more about the trial and becoming involved in it. It would seem that rapport had been built up during the telephone calls and these service users responded well to the researcher. Despite this apparent interest, the service users both withdrew their expressions of interest. It would appear that they had not felt that they could express their true views when conversing with the researcher, as they were keen to please and not disappoint.

I arranged an appointment with the service user who sounded keen. I arrived at their house and they were not there. I rang the service user and they said they had forgotten and so I arranged another appointment. I rang them prior to the new appointment to check that they were still available; they said they are not interested and do not want to meet up despite having arranged meeting previously. (MS, 40 years old, UK-born Pakistani male)

I spoke to the service user on the phone, they sounded eager to set up appointment, so a provisional date was set. Prior to the appointment date, the service user texted me to cancel the appointment and said they would text back in a day or two to set a new appointment. I had not heard back from them so I texted them a week later to see if wanted to rearrange, to which they replied ‘no but thanks!’ In this case they obviously didn’t feel that they could say no to the researcher when speaking over the phone. (FD, 25 years old, UK-born Indian female)

-

Needing Time to Decide

Providing sufficient time to reflect on study information was crucial to recruiting South Asian participants. This provided extra time and opportunity for the participants to discuss this within the family which helped them arrive at a decision about their participation.

The participant expressed initial interest in participating and requested that they have some time to think about it and discuss it with their son. (MI, 53 years old, Pakistani-born male)

It was decided that the participant should be given time to digest the information about the study and so information sheets were left with her and her husband. (AW, 53 years old, African-born Indian female)

-

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first attempt to describe experiences of field researchers in recruiting any specific ethnic group into mental health research within the UK. Therefore, this work gives us an opportunity to study the barriers and facilitators of recruiting this group for the first time. The diary accounts have provided a detailed insight into field staff experiences in the recruitment process and can aid learning in the future with regards to overcoming barriers. Being aware of potential barriers can assist with the design of future trials as issues to be aware of can be highlighted and solutions to overcome barriers can be planned in advance. This is helpful to know at the time of trial design stage as it can assist with the writing of the protocol and the trial financial costing.

The barriers that have emerged from the diary entries to successfully recruiting South Asian participants into research were categorised into three groups. In order for the potential barriers to recruitment to be overcome, a priori mechanisms should be in place in advance of the recruitment period.

Those barriers that can be overcome without any extra effort are largely independent of ethnicity per se, although there is an ethnic variation in the way these barriers present and therefore cultural consideration is needed to resolve them. For example, when considering the timing of appointments, child care issues would be important to consider regardless of the ethnicity of the participants; however, the options available to overcome this obstacle show wide variation. White households commonly practice employing a paid child minder, whereas this concept is unfamiliar within South Asian families, who are more dependent upon their family network. A cultural understanding of the target sample will help in tailoring the initial approach made to the participants. This is evident within our recruitment process as it has been reported that 13 out of the 23 ethnic minority participants did not need any additional resources beyond the standard recruitment procedures. It is therefore essential to provide training for field staff to ensure that researchers follow best practice guidelines in their interactions with participants.

Within the category of resource-based barriers, bilingual information and interpreters are the most important resources to incorporate into trial design and recruitment processes. It is important in the costing of a study to consider the need for translation work to be undertaken and to cater for the provision of interpreters. It is also important in terms of the time allocated for the recruitment of participants and additional work that may need to be completed.

Training needs barriers may not be addressed through standard practice and it is important that they are addressed through training at every stage of trial design and implementation. It is beneficial to have expertise on board in the area of ethnic minority recruitment. Cultural sensitivity training should be provided to all people on the research team.

In particular, this paper highlights the need to include more training to clinical staff who may be actively involved within the research process. Within this trial, there were two tiers of recruitment, with the care coordinator having a key role as the ‘gatekeeper’ to the participants. On occasions, care coordinators would inform researchers that participants had refused their involvement in the trial, without elaborating on any reasons and blocking researchers from making further enquiries. Their failure to divulge additional information has therefore left a gap in knowledge on these occasions, relating to participants’ reasons for refusal; hence any barriers which may have been overcome were left unaddressed.

Within this two-tiered approach to recruitment, it is the researchers who have the enhanced knowledge of the trial and research process, so are aware of both the research topic and the importance of cultural sensitivity. Therefore, the second tiers (care coordinators) also need to have this enhanced knowledge and appreciation of cultural sensitivity through more focussed training. It is important that they have the skills to appropriately introduce their service users to the broader concept of research and to the specific trial. Within the field researchers’ experiences, it is noted that one care coordinator did not know the service user’s first language and had not recognised the importance of this and options available to assist communication with their client.

There are two main comparisons which are important to make following the findings of this study and these are firstly an assessment between the experiences of recruiting South Asians compared to white British participants within the CRIMSON trial. Secondly, the contrast between the findings from the recruitment of ethnic minority participants into a mental health trial compared with research focussing on other disease categories is important.

The first issue has been earlier alluded to, introducing the relevance of themes for ethnic minority groups per se, compared to the recruitment of white British participants. Whilst the themes emerging are not exclusive to the recruitment of ethnic minority participants, the subtleties in their manifestation require particular care during recruitment. For example, it is not uncommon to include families within the recruitment process for all participants, but the particular nuances of familial involvement take on greater significance when involving South Asian participants. The role of the family (as discussed within the results transcripts) takes a more central role, giving particular consideration to issues of; permission giving, gender dynamics and other family responsibilities held by the participant, which is not common when recruiting white British participants. This also makes direct comparisons with international literature more difficult, considering the diverse ethnic populations of the USA, for example. Terminology also plays an important role as, whilst the term Asian usually refers to people of South Asian origin when used in the UK, in the US Asian is commonly understood to mean people from far Eastern Asian populations. Therefore, when comparing the findings for different ethnic groups across international sources, such issues should be considered. Different solutions are necessary for different ethnic groups despite similarities in overarching barriers.

This paper builds on what was known previously regarding the recruitment of ethnic minority participants within research of different disease categories [12–20] and adds to it through the specific nature of recruiting ethnic minority participants with severe mental illness in the UK. Many of the barriers encountered within the recruitment for this study were comparable with those identified within existing literature. For example, the need for trust between participants and recruiters was identified as a key theme, as was the need for additional resources prior to the recruitment period [23]. Awareness of clinical trials and language barriers were also highlighted within literature [19], which are consistent with current findings. Whilst the barriers encountered by researchers working in other disease areas are often directly applicable in this case, the way in which they manifest themselves for minority groups with mental illness is once again different. For example, whilst consent is a barrier that can be encountered regardless of the disease category, issues with consent in some clinical cancer trials [18] place emphasis on the doctor/client relationship and participant concerns over health deterioration. Consent-related barriers within the CRIMSON trial related to participant insight into their own illness, stigma of mental health and a limited understanding of potential benefits to them. Within clinical trials research [19] limited trust and participants’ concern was often cited as a barrier, although this concern generally centred on the side effects of drugs. This was not noted within the CRIMSON trial, due to the nature of the intervention offered.

One of the most closely aligned studies to the current paper focused on the recruitment of South Asians in UK into a cancer trial [18]. This work considered published international experiences alongside the authors’ own local experiences. Whilst similar observations were made in both, such as stigma, this took a different form when applied to mental health compared to physical health. Within the clinical trial, the authors noted a hierarchy of recruiter, which was not replicated within the CRIMSON trial; whilst a senior medical doctor did have involvement in communication with field researchers (and on occasion directly with the participant), the recruitment was successful throughout where the research assistants were the main recruiters. A common theme across the papers reporting on physical health conditions is that of participants’ fear of detriment to their health through participation; this was not consistent with the findings in CRIMSON, further highlighting some of the specific nuances between recruitment issues in physical health and mental health trials.

Other research into recruitment of ethnic minorities into an obesity trial [15] highlighted the success of recruitment strategies involving community groups and partnerships with relevant organisations; this contrasts to the issues encountered within this paper, where a key role in recruitment was held by their mental health clinician. The stigma of mental health as an issue encountered by ethnic minority participants in the CRIMSON trial spread wider than the effects of participation for themselves, to consider the impact on their family and wider community.

Conclusion

We conclude that by incorporating additional efforts to recruitment ethnic minority participants into the trial, the recruitment rates (percentage of those who were eligible who were recruited into the trial) were almost identical for South Asian participants (50 %) compared with white British participants (51 %).

Through reviewing the barriers raised, this can aid the training and supervision process, allowing researchers to be prepared in advance when conducting trials. For example, barriers that have been highlighted can be discussed and rectified immediately through finding appropriate solutions. This ensures an on-going learning process and can promote ongoing training for the research team and across research trials.

Limitations of the Study

Whilst the findings may be generalised to other ethnic minority participants as a whole, it is clear that the focus of this paper and the barriers reported are specific to South Asian participants. Furthermore, the barriers are specific to those people suffering from severe mental illness. The number of participants recruited from ethnic minorities that are reported on in the diary accounts appears to be small. This said there was repetition of the issues that were encountered across interactions with participants and in majority of cases multiple barriers needed to be overcome.

References

Weich S, Lewis G. Material standard of living, social class, and the prevalence of the common mental disorders in Great Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(1):8–14.

Weich S, Lewis G. Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):115–9.

Nazroo JY. Ethnicity and mental health. London: Policy Studies Institute; 1997.

Weich S, Nazroo J, Sproston K, McManus S, Blanchard M, Erens B, et al. Common mental disorders and ethnicity in England: the EMPIRIC study. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1543–51.

King M, Coker E, Leavey G, Hoare A, Johnson-Sabine E. Incidence of psychotic illness in London: comparison of ethnic groups. BMJ. 1994;309(6962):1115–9.

Cooper C, Morgan C, Byrne M, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Hutchinson G, et al. Perceptions of disadvantage, ethnicity and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(3):185–90.

Eaton W, Harrison G. Ethnic disadvantage and schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000;102(407):38–43.

Hurrell A, Waheed W. The impact of an inability to communicate in English on the inclusion of ethnic minorities within mental health research: conference proceedings, MHRN National Scientific Meeting, March 20, 2013, London;2013.

Lloyd CE, Johnson MR, Mughal S, Sturt JA, Collins GS, Roy T, et al. Securing recruitment and obtaining informed consent in minority ethnic groups in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:68.

Sin CH. Sampling minority ethnic older people in Britain. Ageing Soc. 2004;24(2):257–77.

Brown G, Marshall M, Bower P, Woodham A, Waheed W. Barriers to recruiting ethnic minorities to mental health research: a systematic review. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(1):36–48.

Jolly K, Lip GY, Taylor RS, Mant JW, Lane DA, Lee KW, et al. Recruitment of ethnic minority patients to a cardiac rehabilitation trial: the Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation (BRUM) study [ISRCTN72884263]. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:18.

Sheikh A, Halani L, Bhopal R, Netuveli G, Partridge MR, Car J, et al. Facilitating the recruitment of minority ethnic people into research: qualitative case study of South Asians and asthma. PLoS Med. 2009;6(10):e1000148.

Godden S, Ambler G, Pollock AM. Recruitment of minority ethnic groups into clinical cancer research trials to assess adherence to the principles of the Department of Health Research Governance Framework: national sources of data and general issues arising from a study in one hospital trust in England. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(6):358–62.

Samsudeen BS, Douglas A, Bhopal RS. Challenges in recruiting South Asians into prevention trials: health professional and community recruiters’ perceptions on the PODOSA trial. Public Health. 2011;125(4):201–9.

Douglas A, Bhopal RS, Bhopal R, Forbes JF, Gill JM, Lawton J, et al. Recruiting South Asians to a lifestyle intervention trial: experiences and lessons from PODOSA (Prevention of Diabetes & Obesity in South Asians). Trials. 2011;12:220.

Rooney LK, Bhopal R, Halani L, Levy ML, Partridge MR, Netuveli G, et al. Promoting recruitment of minority ethnic groups into research: qualitative study exploring the views of South Asian people with asthma. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(4):604–15.

Symonds RP, Lord K, Mitchell AJ, Raghavan D. Recruitment of ethnic minorities into cancer clinical trials: experience from the front lines. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(7):1017–21.

Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: a review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(5):382–8.

Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 28;2006.

Gater R, Tomenson B, Percival C, Chaudhry N, Waheed W, Dunn G, et al. Persistent depressive disorders and social stress in people of Pakistani origin and white Europeans in UK. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(3):198–207.

Jacob KS, Bhugra D, Mann AH. A randomised controlled trial of an educational intervention for depression among Asian women in primary care in the United Kingdom. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48(2):139–48.

Dilworth-Anderson P. Introduction to the science of recruitment and retention among ethnically diverse populations. Gerontologist. 2011;51 Suppl 1:S1–4.

Barnett J, Aguilar S, Brittner M, Bonuck K. Recruiting and retaining low-income, multi-ethnic women into randomized controlled trials: successful strategies and staffing. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(5):925–32.

Hussain-Gambles M, Leese B, Atkin K, Brown J, Mason S, Tovey P. Involving South Asian patients in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(42):iii1–109.

Office for National Statistics. Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census/key-statistics-for-local-authorities-in-england-and-wales/rpt-ethnicity.html. Accessed 11 Aug 2013.

Bhugra D, Hicks MH. Effect of an educational pamphlet on help-seeking attitudes for depression among British South Asian women. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(7):827–9.

Kai J, Hedges C. Minority ethnic community participation in needs assessment and service development in primary care: perceptions of Pakistani and Bangladeshi people about psychological distress. Health Expect. 1999;2(1):7–20.

Thornicroft G, Farrelly S, Birchwood M, Marshall M, Szmukler G, Waheed W, et al. CRIMSON [CRisis plan IMpact: Subjective and Objective coercion and eNgagement] protocol: a randomised controlled trial of joint crisis plans to reduce compulsory treatment of people with psychosis. Trials 11. 2010.

Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Hull S, Priebe S, Mole F, Feder G. Ethnic variations in pathways to and use of specialist mental health services in the UK. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:105–16.

Dein K, Williams PS, Dein S. Ethnic bias in the application of the Mental Health Act 1983. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(5):350–7.

Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, Bagalkote H, Morgan K, Fearon P, et al. Pathways to care and ethnicity. 2: source of referral and help-seeking: report from the AeSOP study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(4):290–6.

Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, Bagalkote H, Morgan K, Fearon P, et al. Pathways to care and ethnicity. 1: sample characteristics and compulsory admission: report from the AeSOP study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(4):281–9.

Singh SP, Greenwood N, White S, Churchill R. Ethnicity and the Mental Health Act 1983. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:99–105.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. 2011.

Acknowledgments

Professor Birchwood was part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaborations for leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC-BBC) programme. The views in this paper are not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health. The CRIMSON trial is funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Department of Health. We would like to acknowledge the Mental Health Research Network and the Trial Steering Committee for their assistance in the set up and conduct of the trial. We are grateful for the assistance of the clinical teams in each of their sites for their participation in the trial (trial website: http://crimson.iop.kcl.ac.uk/)

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, G.E., Woodham, A., Marshall, M. et al. Recruiting South Asians into a UK Mental Health Randomised Controlled Trial: Experiences of Field Researchers. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1, 181–193 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0024-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0024-4