Abstract

Background

Although the population of diverse applicants applying to medical school has increased over recent years (AAMC Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012); efforts persist to ensure the continuance of this increasing trend. Mentoring students at an early age may be an effective method by which to accomplish diversity within the applicant pool. Having a diverse physician population is more likely able to adequately address the healthcare needs of our diverse population.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to initiate a pipeline program, called the Medical Student Mentorship Program (MSMP), designed to specifically target high school students from lower economic status, ethnic, or racial underrepresented populations. High school students were paired with medical students, who served as primary mentors to facilitate exposure to processes involved in preparing and training for careers in medicine and other healthcare-related fields as well as research.

Methods

Mentors were solicited from first and second year medical students at the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix (UACOM-P). Two separate cohorts of mentees were selected based on an application process from a local high school for the school years 2010–2011 and 2011–2012. Anonymous mentee and mentor surveys were used to evaluate the success of the MSMP.

Results

A total of 16 pairs of mentees and mentors in the 2010–2011 (Group 1) and 2011–2012 (Group 2) studies participated in MSMP. High school students reported that they were more likely to apply to medical school after participating in the program. Mentees also reported that they received a significant amount of support, helpful information, and guidance from their medical student mentors. Overall, feedback from mentees and mentors was positive and they reported that their participation was rewarding. Mentees were contacted 2 to 3 years post MSMP participation as sophomores or juniors in college, and all reported that they were on a pre-healthcare career track.

Conclusion

The MSMP may serve as an effective pipeline program to promote future diversity in college and graduate training programs for future careers in science and medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well documented that pipeline programs to support careers in medicine and science that seek to diversify health professions are limited. Thus, this contributes to the limited pool of diverse student populations applying in higher education systems such as medical school. For example, in 2011, 54.7 % of medical school applicants were Caucasian, followed by Asians (20 %), African Americans (6.8 %), Hispanics (8 %), foreign applicants (4 %), other/unknown (3.43 %), multiple races (2.7 %), Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (0.2 %), and American Indians/Alaskan natives (0.2 %) [1]. Ultimately from each of these groups, 64.8 % Caucasians, 61.8 % of Asians, 55.8 % of African Americans, 64.9 % Hispanics, 23.8 % foreign, 68.7 % multiple races, 58.7 % other/unknown, 33.3 % of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders, and 59.0 % of American Indians and Alaskan natives, applicants were accepted [1]. Far fewer ethnic minorities are even applying to medical school than would be expected due to their representation in the general population.

In a recent publication by the Association of American Medical Colleges [1], the need for more diverse physician-scientists and physicians was emphasized [1]. Even though diversity among medical school applicants has been increasing [1], more efforts are needed to ensure persistence in this trend. Although this publication included discussion regarding ethnicity and race, it did not discuss the specific socioeconomic status of the medical applicants or the matriculants [1]. However, it could be assumed that the higher the family financial support expected in medical school, the higher the socioeconomic status. Interestingly, ranking from increasing to decreasing family financial support per ethnic group from that report is as follows: Asian, White, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Hispanic, and lastly African American [1]. A study conducted on the financial background of medical school applicants in 2005 and 2006 found that parental socioeconomic status was positively related to academic opportunities for their offspring [2].

One solution to increasing the population of students coming from lower socioeconomic backgrounds as medical school applicants is to reach out to middle school and high school populations from underrepresented groups and provides them with richer academic learning environments to prepare for future success in higher education. Past studies have documented that middle and high school students tend to lose interest in science early on and their attitudes towards success decrease drastically making it difficult for them to even succeed past college [3]. A lack of mentors from within the field has been, in part, reported to contribute to this [4]. Thus, the critical phase in their education when students must be targeted for mentorship opportunities is as early as grade school, middle school, and high school.

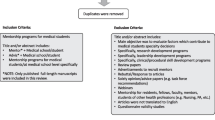

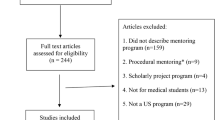

Even though many pipeline programs exist, there is limited literature available as to the implementation and efficacy of the programs [5]. We conducted a literature review to assess the existence and efficacy of programs focused on mentoring high school students for preparation to apply to medical school. Few studies were found that included providing mentorship at the level of high school [6–11]. The few that did exist were summer programs that reported positive long-term outcomes in terms of the mentees attending college or being employed in a healthcare career. One study did not follow participant outcomes after the initial intervention [6]. Almost all programs had no formal component of mentoring or long-term interventions [6–11]. The Stanford program was an exception to this (and also reported significant positive outcomes) as it supported the students even after completion of the summer program with mentoring being incorporated into the program [11].

The literature for pipeline programs for younger populations of students interested in healthcare careers including medicine is critically lacking. The goal of this study was to initiate a pilot pipeline program for those interested in a possible career in medicine/research or other health-related fields with an emphasis on mentoring designed specifically for high school students from lower economic status, ethnic or racial minorities, and other underprivileged backgrounds in Arizona. Here, we report the preliminary findings of this program.

Methods

We obtained an exemption for the study from the University of Arizona Internal Review Board (IRB) in 2009, along with site approvals from the Office of Outreach and Multicultural Affairs at UACOM-P and a local high school. The high school selected for the pilot program was based on its proximity to the UACOM-P and because its student population met the program target population as described above. We obtained corresponding administrative approvals and security clearance. We also obtained Commitment for Underserved Persons (CUP) approval from UACOM-P so that medical students could receive volunteer credit hours through the program. Internship approval was cleared from high school officials and the school’s principal, enabling the high school students to get internship credits for their time spent on the medical school campus. These mechanisms were effective and provided both mentors and mentees additional incentives to participate.

We recruited principal investigators from the Department of Basic Medical Sciences, the core research department at the UACOM-P with active research programs, to provide laboratory shadowing opportunities for mentees interested in learning about basic and translational research. We solicited medical student mentors via email using the UACOM-P Listserv. Mentee applicants were solicited based on a verbal announcement made by the high school internship coordinator to the senior and junior classes. All mentor and mentee applicants were asked to submit a one-page essay describing their interest in the program, qualifications, goals for participation, and expectations. This was carried out to ensure participant’s commitment. Due to the excellent pool of applicants, all mentees that applied ended up with acceptance to the program. An equivalent number of screened mentors were selected so that every mentee could be paired up with a medical school student mentor. Mentors were selected based on their motivation, enthusiasm, and willingness to dedicate their time to the MSMP.

A faculty member along with a staff member reviewed all the applications and matched mentors and mentees based on common interests. For example, if a mentee wanted to learn about the college application process and that was something that the mentor had mentioned in their application essay, then the two were paired. Ratio of mentee to mentor was 1:1. Mentee and mentors were introduced at an orientation session that was held at the start of each new round of the MSMP. The orientation session included presentations from the Office of Outreach and Multicultural Affairs (OMA), UACOM-P campus safety, UACOM-P Biosafety operations, and the founding MSMP investigator. Each medical student mentor was charged with providing individualized mentoring agendas for their mentee and offered opportunities which included, but were not limited to attend a class lecture(s), case-based instruction sessions, doctoring sessions, laboratory shadowing opportunities, and faculty supervised mentor/mentee meetings to discuss various topics such as the college application process in addition to MSMP sponsored group events. Group events included pizza socials and lectures from volunteer faculty and staff speaking on topics of interest such as pre-medical college requirements and current research topics.

A survey was administered to all mentees and mentors before and after participation in the MSMP in order to evaluate program efficacy and collect suggestions for program improvement. Surveys were collected by an OMA staff member before being given to the study investigators, and mentee mentor identification was kept anonymous. The pre-participation surveys were administered during orientation, and post-participation surveys were administered during the last group event of the school year. Mentees were encouraged to keep in touch with their mentors, principal investigators, and school administration after completion of the program.

The survey questions and responses are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the Results section. A Likert scale of 1 to 5 was used for most of the survey questions with options for selection: 1; strongly disagree, 2; disagree, 3; neither agree nor disagree, 4; agree; and 5; strongly agree. We also collected demographic data and narrative responses which are described below. All Likert scale survey responses were entered into Microsoft Excel 2007 for calculation of basic descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation). Finally, as a follow-up, participants were contacted by the primary investigator 2 to 3 years post MSMP via provided contact mechanisms when signing up from the program. An inquiry was made regarding their current academic status as to whether they were enrolled in college/university and if so what were they pursuing as a major.

Results

Demographics of MSMP Participants

The inaugural group of mentors and mentees were oriented in the spring of 2011 (Group 1) and the second group in the fall of 2011 (Group 2). Group 1 included seven mentors and seven mentees. The high school mentees included two juniors and five seniors, out of which four were females and three males. Two reported being from a low socioeconomic status (SES) and five were from a middle SES. Three were Hispanic, one Native American, one black, and one white. None of the mentees reported having a physician family member(s). The medical student mentors included four first year students, three second year students, out of which six were females and one male. Four reported being from middle SES, two low SES, and one high SES. Two were Asian and five were white. Two of the medical student mentors reported having at least one physician family member prior to entering medical school.

Group 2 began with nine mentors and nine mentees. However, only eight of the nine mentee surveys were completed for this group. All mentees in this group were seniors, with six females and two males. Four were from a low SES and four from a middle SES. Four were Hispanic, two black, one Asian, and one was white. One mentee reported having a physician family member. The mentors included seven first year medical students, one second year medical student, and one third year medical student, of which seven were female and two were male. Seven were from middle SES, one from low SES, and one from high SES. Six were white, one Hispanic, one black-Hispanic, and one chose not to answer. Two of the mentors reported having a family member who is physician.

Summary of Mentee/Mentor Narrative Responses

Medical student mentors and high school mentees reported in person or via email contact hours between from 2 to 16 h a week based on the mentee, mentor, or faculty supervisor’s availability. The calculated average amount of time per week that mentees spent with their mentors discussing goals and addressing topics of interest was approximately 2.5 h.

Survey data obtained using the Likert scale are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Table 1 summarizes the pre-participation responses completed by mentees regarding opportunities and preparedness for medical school. Table 2 summarizes high school mentees responses to similar questions asked pre- and post-participation in the MSMP. Table 3 illustrates a series of questions given to mentees evaluating the mentor performance and overall satisfaction with the program post MSMP participation. Table 4 illustrates a summary of questions mentors were asked prior to beginning the mentoring process with assigned mentees. Table 5 illustrates a series of questions given to mentors evaluating their overall thoughts regarding the MSMP post participation.

Mentee expectations as a participant in the MSMP included learning more about a medical student’s everyday life, the application process to get into medical school, the requirements for a successful medical school applicant, and learning more about a the mentoring process. Expected qualities in a mentor included being helpful, understanding, reliable, responsible, and confident. Other qualities included organized, communicative, approachable, and knowledgeable. Obstacles and concerns listed in their pursuit towards a medical education included limited finances, finding family/school balance, not having sufficient study habits, and lack of organizational skills. The most frequently listed reasons for wanting to become a medical doctor or healthcare provider included having the ability to help people, being an advocate for the underserved, and the rewarding aspect of being a physician.

Mentor expectations prior to participation included being able to help their mentee explore a future in medicine, provide support and encouragement to their mentee, have fun, and provide guidance as needed. The qualities they would look for in a mentee included: “Willingness to learn; open to asking questions; driven and passionate about life/ career; curious about the medical profession; committed to program and activities; professional, accountable; open to sharing concerns about achieving goals; willingness to ask for help; interest in pursuing a goal; interest in medical career; willingness to rise above challenges; flexibility; interested in developing relationships; punctual, enthusiastic, and communicative.” Obstacles mentors experienced prior to medical school matriculation included: “No one to talk to about applying; no financial support and related admission issues; help with the decision to become a physician; financial support and debt; indecision; cost of a medical education; no family in the medical field; knowing how to apply; doing well in college; and stress”. In addition, they added: “Finding my way; not knowing anyone who went through the medicals school application process; no guidance, applications, MCAT schedule/preparation and timeline; maintaining full time work and school and overcoming family dysfunction growing up; financial; fear of not getting into school to accomplish dream; passion for art; and had a hard time deciding on career.”

College Acceptance Success

All MSMP mentees reported success in the college application process and further reported acceptance into a 2-year or 4-year college/university. It is unknown whether or not their classmates, who were not participating in MSMP, also got into college. Based on this information and Likert scores reported in Table 2 (question 3), the success of actual acceptance into college paralleled their self-reported high self-confidence about being accepted into college in their pre- and post-participation survey.

Two to Three Year Post-MSMP Mentee Follow-up

Out of the 16 mentees, 12 mentees replied in response post MSMP follow-up. All at the time were classified as being either sophomores or juniors in college and in terms of declaration of a college major, ten individuals reported being biology majors with an emphasis on a pre-medical track. The 11th person reported studying nursing and while the 12th person reported that they were pursuing a major to prepare for entry into a physician’s assistant program post receiving an undergraduate degree. Interestingly, the nursing student expressed interest in further pursuing a degree medicine following nursing school.

While attending college, six of the past mentees reported that they were working either part-time or full-time while taking classes. Four of the mentees reported that they continued regular contact with their medical school mentors and/or research faculty affiliated with the MSMP. Based on the Likert scores (Table 2; question 4) reporting a high level of confidence about predicting to do well in college, several of the mentee’s during their undergraduate training reported small but significant milestones. For example, one individual was awarded with the Gates Millennium Scholar Undergraduate Award. Other students reported opportunities of participating in bench research as an undergraduate or graduating college a semester early.

Discussion

Based on survey feedback and oral communication with mentees and mentors, the MSMP provided foundational mechanisms for enhanced knowledge and exposure to (1) processes associated with learning how to prepare for medical school, (2) understanding a medical school curriculum for first and second year students, and (3) healthcare professions such as medicine and the basic sciences.

In addition to being recruited as a diverse population, most students were also either from a middle or low SES and had no immediate family members with college experience. The mentees felt that some of the obstacles they needed to overcome included how they would financially fund their college and graduate school education. Interestingly, mentors in the MSMP who were not Caucasians or were from a lower SES were more likely to not have college educated family members and adequate mentorship for medical school. As a result, they reported that the likeliness of a family member’s ability to help pay for their medical education was highly unlikely (Table 4). These findings further reiterate the importance of assisting low SES and minority students with mentorship in an attempt to facilitate their journey towards applying to college, healthcare fields, medical school, and beyond.

Although the interpretation of the surveys collected in this study suggests the importance of mentorship early on in the pipeline, it is acknowledged that based on a small sample size and lack of power for statistical analysis further studies similar to this design will have to be conducted to determine if high school mentoring programs have a significant impact on success rates of matriculating college, entering the healthcare or research fields and even matriculating medical school.

It is also acknowledged that the Likert scale survey may contain bias. For examples, central tendency bias, acquiescence bias, and social desirability bias are inherent to performing a survey. However, measures were taken to decrease bias including making survey responses anonymous, collection of surveys by non-investigators, and breaking down a string of related questions in between other less related questions. Central tendency bias seems to be low given overall survey responses even though no specific measures were taken to avoid this. Given that this is a pilot program and the survey has not been used before, the surveys could be modified further to help decrease these biases.

At the time of inception of the MSMP, the UACOM-P was a newly constructed medical school. Some limitations included infrastructure, since the UACOM-P as not all the facilities and resources were available in the first 2 years of the MSMP. In addition, during its inception, one medical student was managing and overseeing the entire program without much administrative involvement. Another limitation was the number of medical students available to serve as mentors. Therefore, data collected for the first two groups were from a relatively small sample size. But despite being a new medical school with limited facilities and resources available to support the MSMP, there was significant support from faculty and staff. When working with underserved communities, some physical limitations can exist such as location and travel feasibility for student participants. In the case of UACOM-P and the collaborating high school, distance was not a factor. The location of the high school with respect to the medical school was optimal because the high school students were within a short walking distance from the UACOM-P campus serving as ideal venue for activities and mentor/mentee meetings.

Future projections to ensure continued success of the MSMP include incorporation of institutional support for sustainability of an official pipeline program at the UACOM-P with corresponding administrative resources. Additionally, dedicated faculty and staff willing to assist medical student coordinators and mentors in group activities will contribute and ensure success of scheduled mentor-mentee activities as requested by prior program participants. Mechanisms for expansion of the mentee applicant pool to other high schools with diverse populations located in underserved communities within the Phoenix metropolitan area will also be a future goal for the MSMP.

Finally, our program can continue to build on the success of already established programs in existence [6–11]. Particularly, in terms of having a formal curriculum throughout the year for the mentees with a strong focus on the sciences in addition to college admissions [6–11]. Included in the curriculum would be sessions discussing factors that medical schools particularly look for including life experience, community service, clinical experience, and leadership experience [12].

Conclusion

The overall goal in the design of the MSMP was to provide an effective program to help foster the physician shortage in Arizona by creating avenues in the medical school application process for students early in the educational pipeline. Specifically, the MSMP offered high school students with an interest in the medical profession the opportunity to learn more about path to gain entrance into medical school.

It is somewhat premature to evaluate how much the program had an impact on actual medical school applications (as all of the mentees are currently still on college); however, based on feedback from the high school mentees, many reported that they gained insightful knowledge and better understanding of what it takes to navigate the sometimes not so direct but circuitous path towards a higher education. Importantly, the MSMP served as a mechanism for young students to become even more motivated and enthusiastic about a career goal in medicine and other healthcare professions by having mentors closer to them in age to model and learn from. The MSMP also provided them with the confidence needed achieve their goals by pairing them up with a medical student mentor. Many of these students stem from underrepresented communities and have limited access to a mentor or to programs directed at fostering their career goals. Thus, although based on a sample size, the data presented suggest that high school mentoring programs like the MSMP can help even in the smallest of ways.

References

AAMC Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012. (https://members.aamc.org/eweb/DynamicPage.aspx?Action=Add&ObjectKeyFrom=1A83491A-9853-4C87-86A4-F7D95601C2E2&WebCode=PubDetailAdd&DoNotSave=yes&ParentObject=CentralizedOrderEntry&ParentDataObject=Invoice Detail&ivd_formkey=69202792-63d7-4ba2-bf4e-a0da41270555&ivd_prc_prd_key=E1A7507B-F47B-40D0-8946-9ADBAB417F3E5). Accessed 27 Dec 2013.

Kennedy M. Medical School Admissions Across Socioeconomic Groups: an analysis across race neutral and race sensitive admissions cycles. UNT Digital Library. (http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc28440/). May 2010. Accessed 29 Nov 2010.

Kaufman P, Alt MN, Chapman CD. Dropout rates in the United States: 2000. Washington, DC: Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2001.

Thurmond VB, Criegler LL. Why students drop out of the pipeline to health professions careers: a follow-up of gifted minority high school students. Acad Med. 1999;74(4):448–51.

AAMC Summer Programs Web Database. (https://services.aamc.org/summerprograms/getprogs.cfm). Accessed 30 Sept 2014.

McLean AH, Gibbs T, Sugimoto T, Altekruse JM. An enrichment program for South Carolina high school students interested in future biomedical science professions. J Natl Med Assoc. 1983;75(6):603–5.

Acker AL, Freeman JD, Williams DM. A medical school fellowship program for minority high school students. Acad Med. 1988;63(3):155–204.

Cregler LL. Enrichment programs to create a pipeline to biomedical science careers. J Assoc Acad Minor Phys. 1993;4(4):127–31.

Larson J, Atkins RM, Tucker P, Monson A, Corpening B, Baker S. The University of Oklahoma College of Medicine summer medical program for high school students. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2011;104(6):255–9.

Soto-Greene M, Wright L, Gona OD, Feldman LA. Minority enrichment programs at the New Jersey Medical School: 26 years in review. Acad Med. 1999;74(4):386–9.

Winkleby MA. The Stanford Medical Youth Science Program: 18 years of a biomedical program for low-income high school students. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):139–45.

AAMC. Medical School Admissions: More than Grades and Test Scores. (http://www.aamc.org/download/261106/data/aibvol11_no6.pdf). September 2011. Accessed 28 Oct 2014.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend a special thank you to Dr. Ron Hammer, a contributing faculty MSMP mentor at the UACOM-P; members of the Office of Outreach and Multicultural Affairs, Dr. Michael Trujillo, Dr. Doug Campos-Outcalt, and Mrs. Mary Drago, M.A. for their tireless contributions to success of the MSMP. We would also like to thank the many UACOM-P staff members for their technical assistance as well as the principal investigators in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences who opened up their laboratories to our mentees for shadowing and volunteer opportunities.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest or financial involvement with this manuscript. There are no funding sources for this study.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for being included in the study.

Additional informed consent was obtained from all subjects for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, S.I., Rodríguez, P. & Gonzales, R.J. The Implementation of an Innovative High School Mentoring Program Designed to Enhance Diversity and Provide a Pathway for Future Careers in Healthcare Related Fields. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2, 395–402 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0086-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0086-y