Abstract

We contribute to the assessment of the employment implications of the COVID crisis by classifying economic sectors according to the confinement decrees of three European countries (Germany, Spain and Italy). The analysis of these decrees can be used to make a first assessment of the implications of the COVID crisis on labour markets, and also to speculate on mid and long-term developments, since the most and least affected sectors are probably going to continue to operate differently until a vaccine or other long-term solution is found. Using an ad-hoc extraction of EU-LFS data, we apply this classification to the analysis of employment in Germany, Italy and Spain but also UK, Poland and Sweden, in order to cover the whole spectrum of institutional labour market settings within Europe. Our results, in line with recent literature, show that the employment impact is asymmetric within and between countries. In particular, the countries that are being hardest hit by the pandemic itself (Spain and Italy, and also the UK) are the countries more likely to suffer the worst employment implications of the confinement, because of their productive specialisation and labour market institutions. Indeed, these were also the labour markets that were more vulnerable before the crisis: characterised by high unemployment and precarious work (especially temporary contracts).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction to the debate

The COVID-19 crisis hit Europe in the first quarter of 2020. Since January, when the first cases were notified, the number of contagions and deaths has been continuously increasing, and confinement measures and restrictions on economic activities have been implemented in most countries from late February to halt the spread of the virus. After periods of several weeks in which the most restrictive measures were implemented (from late February to April), these measures started to be softened progressively in most countries in May. Although the pandemic is still present and continues evolving, the first available studies on its economic and employment impact seem to converge around similar conclusions: the impact of the crisis is being clearly asymmetric, with the most vulnerable countries and segments of the workforce being hardest hit by the pandemic.

Beland et al. (2020) examine the short-term consequences of COVID-19 on employment and wages in the US. Their findings suggest that COVID-19 increased the unemployment rate, decreased hours of work and labour force participation and had no significant impacts on wages. The negative impacts on labour market outcomes are larger for men, younger workers, Hispanics and less educated workers, indicating that the COVID-19 crisis increases labour market inequalities. They also construct three indices (using ACS and O*NET data) in order to classify jobs according to their exposure to disease, proximity to co-workers and the ability to do remote work, and find that the occupations that depend on physical proximity to others are the ones that are being more affected economically, in contrast to occupations that can be performed remotely. Similar results have been found for the case of Europe. According to Pouliakas and Branka (2020) and Fana et al. (2020), the segments of the workforce most likely to be impacted by social distancing measures and practices due to the COVID-19 pandemic are the most vulnerable groups, such as women, non-natives, those with non-standard contracts (self-employed and temporary workers), the lower educated, those employed in micro-sized workplaces and low-wage workers. In line with these findings, Palomino et al. (2020) find that the crisis is producing in all European countries increases in the levels of inequality and poverty. However, these differences among workers with different employment status and conditions are related to some degree to the segregation of different types of workers across economic sectors. In particular, precarious and vulnerable workers are over-represented in activities related to entertainment, hospitality and tourism, and more generally low productivity services which are facing the hardest short-term impact in the COVID crisis due to both the economic lockdown and the confinement measures (Fana et al. 2020). Barrot et al. (2020), using data from France, show that the decrease in employment caused by social distancing measures is the highest in hotel and restaurants; arts and leisure; agriculture; service activities; food; wholesale and retail and construction, and the lowest in computer services; telecommunications and consulting and scientific and technical activities. They also analyse the effects of social distancing on value added growth for each sector, and find that the sectors experiencing greater losses are mining; arts and leisure; technical activities; food, hotel and restaurants. At the bottom of the figure, with the smallest losses on value added growth, are real estate activities; computer services; scientific research and service activities.

In line with the previous findings, data from the US suggest that entertainment, restaurants and tourism face large supply and demand shocks (del Rio-Chanona et al. 2020). At the occupation level, the same authors show that high-wage occupations are relatively immune from adverse supply and demand side shocks, while low-wage occupations are much more vulnerable.

The intensity of the economic effect strongly depends on country specialisation. Countries relying more on low productive service activities and with a low share of public employment are the most hardly hit. A recent survey conducted by Eurofound (2020) shows that the share of people reporting that their working time during the COVID-19 pandemic decreased (a lot or a little) is above the EU average in all Mediterranean countries. These results are in line with the estimates of Fana et al. (2020), showing that the share of employment in sectors that are forcefully closed by confinement measures and therefore inactive during the COVID crisis is highest in some Mediterranean countries (Malta, Cyprus, Spain, Greece, Italy) and Ireland, while the proportion is below the average in most Nordic, Easter and central European regions. In summary, in Europe the Mediterranean countries are the ones that are being hardest hit by employment implications of the pandemic.

An important point to emphasize is that the employment and economic impact of the COVID crisis in each country will in the medium-long term be much less determined by the strictness of the confinement than by structural and institutional differences such as economic specialisation, social protection and labour market regulation. In fact, the economic effect of the pandemic occurs regardless of whether governments mandate an economic lock-down or not, as a recent experiment suggests (Andersen et al. 2020).

Additionally, the position of each country in the international division of labour as it results from the integration in complex value chains will play a pivotal role in the medium term. This is particularly important for European countries whose productive structures evolved asymmetrically in the last decades, with both Southern and Eastern periphery being more dependent on the Center, led by the German productive model (Simonazzi et al. 2013).

In this context, Barrot et al. 2020 suggest that a more severe contraction of GDP can be expected in both Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Lithuania) as well as some Mediterranean ones, although different confinement measures have been applied in both cases. The Nordic countries, on the other hand, appear as the ones facing the best scenario. Doerr and Gambacorta (2020) find that, in general, employment in regions in Southern Europe and France is more exposed to the negative effects of the pandemic than regions in northern Europe, with Eastern and central European regions in between.

In the context of the current crisis, telework has allowed to mitigate part of the negative consequences caused by social distancing and restrictions on activities. Working from home requires important changes in the lifestyle of workers and, as a consequence, creates new challenges for work-life balance, mental health issues and work organisation practices. But in terms of employment, it is a practice that allows people to maintain their activity (and income) even when the strictest restrictions are imposed, at least for those with standard employment arrangements. In this sense, telework helps those that are able to perform their professional activity remotely to dodge the economic impact of the crisis. But not all workers can benefit from this form of work.

According to Dingel and Neiman (2020), the share of jobs that can be done at home exceeds 40% in Sweden and the UK, while the proportion decreases in the cases of France (38%), Italy (35%) or Spain (32%). A similar divide between the north and the south of Europe has been documented by Palomino et al. (2020). Thus, the potential for telework seems to be lower in the countries that are being hardest hit by the COVID crisis. As a result, the Mediterranean countries are not only severely affected by the crisis, but also worse prepared than other EU countries for the large-scale transition to telework triggered by the crisis. Also, we have to consider that the expansion of telework has consequences in terms of inequality not only across countries, but also within countries and across groups of workers. The jobs that can more easily shift to telework have, on average, higher wages and qualifications. According to Dingel and Neiman (2020) estimates, among high-paid activities 83% of jobs can be done at home for educational services; 80% for professional, scientific and technical services; 79% for management of companies and enterprises, etc.; conversely, among low-paid activities only 14% for retail trade; 8% for agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting and 4% for accommodation and food services can be performed remotely.

In this paper, we contribute to the assessment of the employment implications of the COVID crisis by classifying economic sectors according to the confinement decrees of three European countries (Germany, Spain and Italy). The analysis of these decrees, which explicitly classify economic sectors as essential or non-essential, and in some cases specify sectors that must be forcefully closed, can be used to make a first assessment of the implications of the COVID crisis on labour markets, and also to speculate on mid and long-term developments, since the most and least affected sectors are probably going to continue to operate differently until a vaccine or other long-term solution is found.

2 Methodology

The present study is based on a detailed comparative analysis of the sector lockdowns in three European countries: Germany, Spain and Italy, as they result from national confinement decrees approved in March 2020. The three countries analysed have regulated the productive lockdown by identifying essential and not essential activities, broadly related to the satisfaction of fundamental needs: health, food, security, education and administrative services. Moreover, in the three countries as well as in most other countries, the firms that are allowed to operate are instructed to meet stringent health and safety requirements for their employees.Footnote 1

After a detailed qualitative analysis of the confinement decrees summarized in Table 3 of the "Appendix", for each specific sector (NACE at the 2-digit level) and country we provide an indicator that ranges from 0 to 1. A value of 1 indicates that the sector is explicitly defined as essential, and thus can continue to operate even in the strictest confinement. A value of 0 indicates that the sector is considered non-essential, which may mean that it is forcefully closed or that it can operate only under certain conditions. Values between 0 and 1 indicate that some sub-sectors (NACE 3 or even 4 digit codes) within a given sector (NACE at 2 digits, which is our baseline) are considered essential and some not: in these cases, the value of the indicator reflects the share of sub-sectors considered essential, when possible adjusted for relative employment shares using EU-LFS data. Then, for each NACE 2-digit sector the values of the three countries are averaged into an overall indicator, which can be interpreted as the average degree to which a given sector is considered essential in the three countries analysed. Then, this indicator has been used to rank the sectors, providing a first criterion to classify them according to the impact of the COVID confinement decrees. The values of the three country-specific indicators, and the aggregate index, can be found in Table 4 in the "Appendix".

Two additional criteria have been established to complete the classification of economic activities according to the decrees. First, whether a given sector can operate via telework, which mostly depends on the nature of economic activity in the sector: in general, activities and services that do not involve direct physical interaction (either with things or with people) can be remotely provided making use of ICT equipment. All the confinement decrees analysed state explicitly that independently of whether a given sector is considered essential or not, whenever possible it should operate via telework. Second, there is also an implicit or explicit differentiation in the decrees of those (non-essential) activities that are forcefully closed because they require direct face-to-face interaction with clients and therefore, they are particularly risky in the context of the COVID pandemic. Thus, the activities which are fully or mostly non-essential (values below 0.3 in the indicator) are classified in two different categories: those that are forcefully closed (5), and those that are mostly non-essential but not forcefully closed (and thus at least partly active, code 4). These two additional criteria are indicated in the column “Notes” of Table 3 in the "Appendix".

Following this procedure (and as shown in the column “Clasif.” of Table 4 in the "Appendix"), the five categories in which we classified economic sectors according to the impact of the COVID confinement measures are summarised in Table 1.

Using an ad-hoc extraction of EU-LFS data,Footnote 2 we applied this classification to the analysis of employment in Germany, Italy and Spain but also UK, Poland and Sweden trying to cover a wide spectrum of institutional labour market settings within Europe (Esping-Andersen 1990; Gallie 2009; Hall and Soskice 2001). The analysis of the employment structure across the previously defined sector categories allows to discuss the potential socio-economic effects of the confinement measures in the short-run, but also to speculate on the medium-term prospects (from the end of the confinement to the return to full normality). In the following section we will briefly document the employment distribution across categories in each of the European countries analysed, as well as the age and gender profiles of workers in the sectors classified by the impact of the COVID crisis. Then, we will highlight the differences in terms of employment characteristics, focusing on employment status and duration of contracts, and in terms of average wage levels.

3 Results

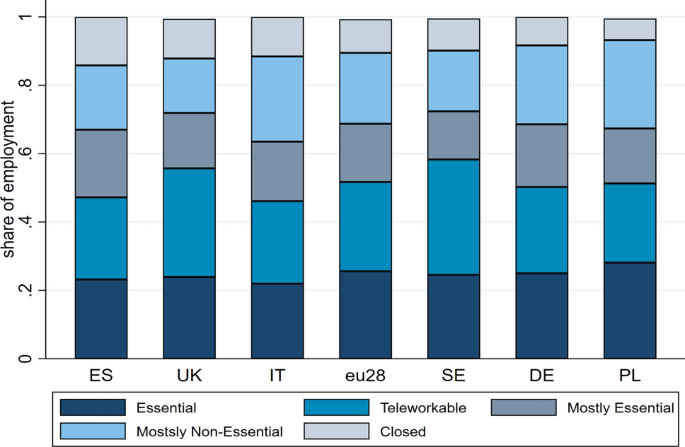

A first impression of the differences across countries is provided by Fig. 1 summarising employment shares in each category. As discussed in the previous section, the categories are sector specific and therefore these patterns are entirely the result of structural differences. In particular, Poland is characterized by the biggest share of employment in essential activities—even higher than the EU-28 average—reflecting the importance in Poland of the primary sector (considered essential in the three confinement decrees analysed) compared to other countries. Indeed, as shown in the European Jobs Monitor 2019 (Hurley et al. 2019), the Polish economy while shifting its productive system toward core manufacturing sectors mainly related to European value chains (anchored to German manufacture industries, Danninger and Joutz 2007), is still characterized by a strong primary sector. On the other hand, employment in sectors active via telework is higher than the EU28 average in Sweden and the UK, but for different reasons: the predominance of the Public Sector in Sweden contrasts with the higher share of financial and professional services in the UK. More heterogeneity emerges between countries when dealing with the manufacturing sector which is split between the categories of mostly essential or mostly non-essential (but in both cases partly active and “not teleworkable”). Spain, Germany and Italy are characterized by an employment share above average in the mostly essential sectors, driven by a relative specialisation in chemical manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade. Furthermore, employment in the mostly non-essential activities (which includes the rest of manufacturing and construction) ranges between 25% for Poland to 15% for the UK. However, the three countries with a strongest manufacturing sector, Germany, Poland and Italy, specialize in different industries and occupy different positions in the European value chain, which will probably lead to different outcomes in the economic crisis ahead (Simonazzi et al. 2013).

Finally, Southern European countries and the UK emerge as those with the highest share of employment in the forcefully closed sectors. These mainly involve accommodation, leisure and tourism as well as personal care activities, all belonging to the category of Less Knowledge Intensive (LTI) services activities. As highlighted by Esping-Andersen (1990), this form of specialisation, especially in the private provision of care services, can be linked to the liberalization of the health sector reinforced by an increase in the demand due to an aging population. At the same time, the high share of employment in tourism and related activities in Italy and Spain is part of a deindustrialization process strengthened by the structural reforms of recent years and the labour market reforms approved after the 2008 crisis, which may have shifted investment towards less innovative and more labour intensive sectors. This last evidence is consistent with the regional polarization analysis presented in the 2019 European Jobs Monitor report, according to which Italy and Spain suffered a downgrading dynamic of their employment structure, compared to the average European trend in the last two decades (Hurley et al. 2019).

Differences in institutional settings and labour market regulations not only result in different employment structures across economic activities but they may have a differential impact on different segments of the population. In other words, the impact of the COVID lockdown decrees (and the COVID-induced economic crisis) vary across population groups, as we will discuss now.

According to Table 2, the two categories that are more gender-segregated (dominated by one gender) are the closed sectors and the mostly non-essential sectors. In the closed sectors, the proportion of women for the EU28 as a whole is 56%, with even higher values in Poland and Germany. On the other hand, the mostly non-essential sectors are very heavily dominated by men, with only 24% of women for the EU28 as a whole. This latter result can be explained by the sectoral composition of the category, mainly driven by manufacturing and construction, which are very male-dominated. The other categories (essential, teleworkable and partly active) are not characterised by a clear gender segregation at the European level, but show a lot of variation by country. For instance, in Germany, Sweden and the UK, women are significantly more prevalent in the essential and teleworkable sectors (Poland also has more women in the latter category). Conversely, for the mostly essential sectors, the share of women is above the EU average in Spain and Poland.

Overall, the asymmetry in the impact of the COVID lockdowns by gender is quite evident for the forcefully closed sectors, which are likely to suffer more also in the mid-long term because of the lockdown and a more than probable decline in final demand for this type of services. However, changes in aggregate demand will shape the overall economic crisis ahead and may particularly hit the most internationally integrated manufacturing sectors, with a potential stronger effect on male workers who dominate those economic activities. However, the differences by gender at the EU level do not seem particularly strong, but they are stronger in some countries such as Poland.

Turning to differences by age, we can observe that higher shares of young workers (those aged 15–29) are found in the closed and to a lesser extent in the mostly essential sectors. But again, differences across countries need to be highlighted. First, Italy and Spain are characterised by a generally low level of youth employment which results in a share below average in all categories. Still, in these two countries young workers are relatively underrepresented in essential, teleworkable and mostly non-essential sectors. This can be explained by the very high average age of public employees, but also the low level of employment in financial and professional activities.

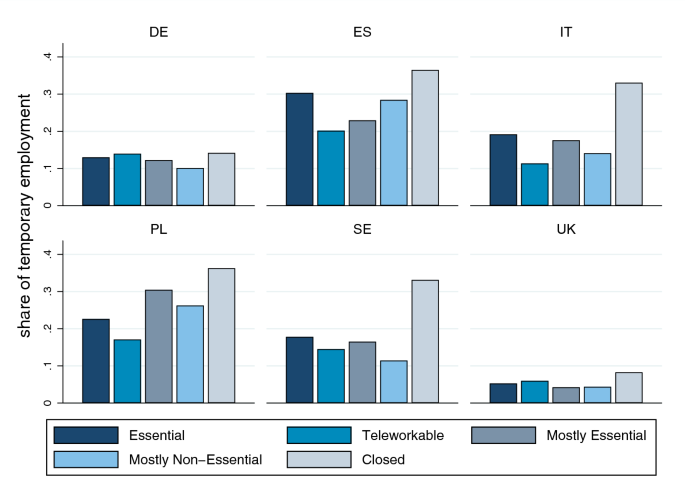

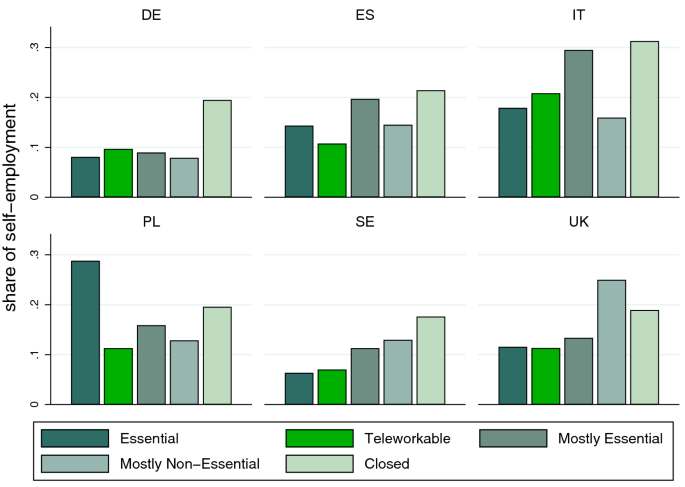

More evident are the differences in labour market regulations, which are related to significant differences in terms of share of temporary (Fig. 2) and self-employed (Fig. 3) workers across categories and countries. For the EU28, temporary employees represent 14% of total employment, but in the forcefully closed sectors the share of temps increases up to 21.6%. As a result of labour market flexibilisation processes occurred in recent decades, in Southern and Eastern countries the proportion of workers with fixed term contracts is higher than elsewhere across all sector categories compared to the other selected countries. The only exception is Sweden, where temporary workers are overrepresented in the closed sectors converging to the Southern countries level. Spain even doubles the average share of temporary employment in all categories but the closed ones. A similar pattern applies to Poland for the most essential and partly active sectors, drawing attention to the precarious character of the impressive employment growth of Poland in the last two decades. A second proxy for precariousness in the labour market is the share of self-employed (without employees) in the total economy. While the self-employed are over-represented in closed activities almost everywhere – 21.6% compared to the 14% across all economic activities at the EU-28 level, suggesting that the self-employed have been hit particularly hard by the Covid-19 crisis (see also Blundell and Machin 2020)—, there exists a remarkable variation across countries. As Fig. 3 underlines, the proportion of self-employed in Poland almost doubles the EU average, followed by Italy. The above figure also suggests that in the two Southern countries, self-employment is over-represented in the mostly essential sectors, where wholesale and retail trade dominate.

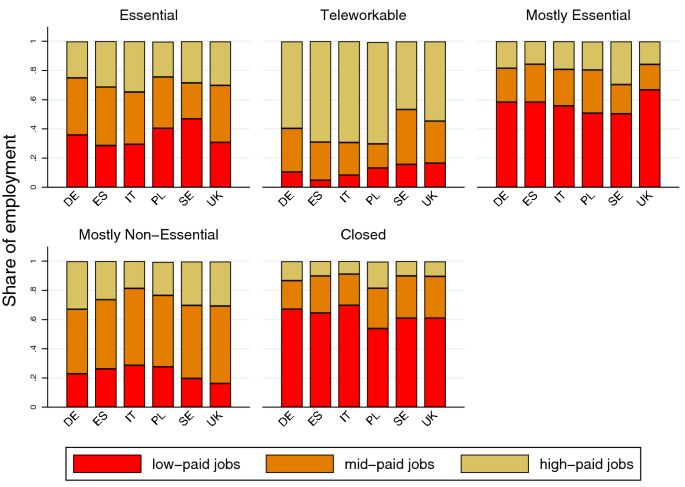

To conclude our analysis of the different employment impact of the COVID confinements by country and sector category, we explore the job-wage distribution in each country-category pair. More precisely, following the approach adopted by Hurley et al. (2019) we rank each occupation-sector combination (jobs) by their average wages in each country, and then assign those jobs to the corresponding job-wage tercile. In other words, the employment structure is partitioned into three terciles—low, mid and high paid jobs—generated by the weighted wage ranking built as an ordinal measure. This way, we are able to compute the share of employment in each tercile by category and country. As underlined by Fig. 4, the closed and mostly essential sectors are not only the more precarious but also those with the highest share of low-paid jobs (60% on average). This evidence thus reflects the vicious nexus between atypical employment and low wages (Raitano and Fana 2019), as well as the relationship between Less Knowledge Intensive Services and low wages. Although in most manufacturing activities mid-paid jobs dominate the wage distribution, the share of low-paid jobs reaches more than the 20% in the countries with a stronger manufacturing base (Germany, Italy and Poland), probably reflecting the effect of wage moderation policies adopted during the last decades.

4 Conclusion and discussion

As expected, the previous analysis reveals very asymmetric effects of the COVID lockdown measures across different groups of workers within and between the selected European countries. In particular, it reveals that the most negative effects tend to concentrate on the most vulnerable and disadvantaged workers in low productivity services. It seems reasonable to assume that the workers more likely to lose their jobs because of the lockdown in the short run, and face a particularly high uncertainty in the mid-term, are the same categories identified in our analysis as the most negatively affected by the COVID confinement measures. These workers are overrepresented in countries where a downgrading dynamic of the economic structure toward low productive services has been recently observed (Hurley et al. 2019). At the same time, medium term effects may extend these negative effects also to countries with a higher share of manufacturing activities mainly dependent on European “core” value chains, as in the case of the automotive sector.

Thus, the negative consequences, unfortunately, tend to pile up. The countries that are being hardest hit by the pandemic itself (Spain and Italy, and also the UK) are the countries more likely to suffer the worst employment implications of the confinement, because of their specialisation in sectors which are more likely to be forcefully closed. In fact, these were also the countries that were most vulnerable before the crisis: characterised by high unemployment, precarious work (especially temporary contracts), inequality and relative poverty compared to the rest of the EU. Unfortunately, Spain and Italy were also the countries most affected by the financial crisis and both fiscal consolidation and structural reform packages. The current crisis, therefore, is likely to exacerbate ongoing economic asymmetries in Europe, as well as pre-existing inequalities in general, unless very drastic policy measures are implemented very quickly, with a decisive redistributive component also at the EU level.

A recent ad-hoc survey carried out by Eurofound (2020) paints a stark picture of people across the 27 EU Member States who have seen their economic situation worsen and are deeply concerned about their financial future. The same survey also showed a dramatic fall in trust in the EU and their national governments, an observation that warns about the possible political consequences of the crisis at all levels in the short and the mid-term. All these concerns and problems are likely to be intensified in the countries that are being hardest hit by the current crisis.

The COVID crisis is so deep that it will not only radically affect labour markets in the short and medium run, but it can also change substantially the way the work is organised. Telework may be here to stay, as recent data suggest, but this is not the only transformation. Early evidence from Italy suggests that industries employing more robots per worker in production tend to exhibit a lower risk of contagion due to Covid-19 (Caselli et al. 2020). As has already happened with telework, automation could be accelerated in the aftermath of the crisis since it can be used as a strategy to minimize risks for health while preserving production and economic activity.

The possibilities for economic recovery are very uncertain to say the least and strongly depend on the economic policies adopted both at the national and European level. As in any deep crisis, we will have to face sharp economic restructuring within and between countries as operating margins, income and demand fall sharply in the following months and years. Ten years after the last crisis, we are now aware that a narrow focus on fiscal consolidation and exports as the main exit strategy resulted in asymmetric weaknesses and vulnerabilities that are again surfacing in the last few months.

While it is imperative that European economies provide income support to the most affected groups as soon as possible, a longer term vision should be put in place for confronting the still severe effects of deindustrialisation in many European countries and for reversing the recent narrowing of social welfare: for instance, by fostering alternative sources of economic growth at a properly large scale (i.e. EU Green Deal) and by setting the foundations a future European Welfare State.

Notes

In particular, the comparative analysis is based on the Recommendations from the Minister of Health and the Agreement between the Chancellor and the heads of state for Germany, approved respectively on March 16th and 22nd. For the Italian case, we use the decree approved on March 10th containing urgent measures at the national level, and the one approved on March 25th, Urgent Measured to tackle the epidemiological emergency related to Covid-19. Finally, the Spanish analysis is based on two main Royal decrees: the first one was approved on March 14th (Royal Decree 463/2020) and declared the State of Alarm in the country, while the second one (Royal Decree 10/2020) was approved on March 29th) and identified the activities considered essential. More info on the content of the main decrees regulating activities can be found in Table 3.

The ad-hoc extraction is based on 2018 annual data and uses Nace rev.2 classification for economic sectors, therefore the analysis provided do not need any reclassification over time and across countries.

References

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh, C. (2020). The large and unequal impact of COVID-19 on workers. https://voxue.org. Accessed 15 May 2020

Andersen, A. L., Hansen, E. T., Johannesen, N., & Sheridan, A. (2020). Pandemic, shutdown and consumer spending: lessons from scandinavian policy responses to COVID-19. Papers arXiv, May 2005.

Barrot, J.-N., Basile, G., & Sauvagnat, J. (2020). Sectoral effects of social distancing. Covid Economics, Centre for Economic Policy Research, 3, 85–102.

Béland, L.-P., Brodeur, A., & Wright, T. (2020). The short-term economic consequences of COVID-19: exposure to disease, remote work and government response. IZA Discussion Paper Series (13159).

Blundell, J., & Machin, S. (2020). Self-employment in the Covid-19 crisis. A CEP Covid-19 analysis, Paper No. 003, Centre for Economic Performance: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Caselli, M., Fracasso, A., & Traverso, S. (2020). Mitigation of risks of Covid-19 contagion and robotisation: evidence from Italy. Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers, The Centre for Economic Policy Research.

del Rio-Chanona, R. M., Mealy, P., Pichler, A., Lafond, F., & Farmer, J. D. (2020). Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: An industry and occupation perspective. Covid Economics, Centre for Economic Policy Research., 6, 65–103.

Danninger, S., & Joutz, F. (2007). What explains Germany’s rebounding export market share? IMF Working Paper no. 24.

Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? White Paper: Becker Friedman Institute.

Doerr, S., & Gambacorta, L. (2020). Covid-19 and regional employment in Europe. Bulletin of the Bank for International Settlements, (16).

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). Social foundations of post-industrial economies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Eurofound. (2020). Living, working and COVID-19—first findings—April 2020. Dublin: Eurofound.

Fana, M., Tolan, S., Torrejón Pérez, S., Urzi Brancati, M. C., & Fernández-Macías, E. (2020). The COVID confinement measures and EU labour markets. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Gallie, D. (Ed.). (2009). Employment regimes and the quality of work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). An introduction to varieties of capitalism. op cit, 21–27.

Hurley, J., Fernández-Macías, E., Bisello, M., Vacas, C., & Fana, M. (2019). European Jobs Monitor 2019: Shifts in the employment structure at regional level. Eurofound and European Commission Joint Research Centre, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Madrid. (2020). Informe del Estudio sobre el impacto de la situación de confinamiento en la población de la ciudad de Madrid, tras la declaración del estado de alarma por la pandemia COVID-19. Impacto económico y laboral sobre los hogares. Madrid, Dirección General de Innovación y Estrategia Social.

Palomino, J. C., Rodríguez, J. G., & Sebastián, R. (2020). Wage inequality and poverty effects of lockdown and social distancing in Europe. INET Oxford Working Paper (No. 2020-13).

Pouliakas, K., & Branka, J. (2020). EU jobs at highest risk of COVID-19 social distancing: is the pandemic exacerbating the labour market divide? Cedefop—Working Paper Series.

Raitano, M., & Fana, M. (2019). Labour market deregulation and workers’ outcomes at the beginning of the career: Evidence from Italy. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 51(2019), 301–310.

Simonazzi, A., Ginzburg, A., & Nocella, G. (2013). Economic relations between Germany and southern Europe. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 37(3), 653–675.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The paper reflects authors’ own opinions and does not involve the Institution they belong.

Code availability

Upon request.

Availability of data and material

Upon request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fana, M., Torrejón Pérez, S. & Fernández-Macías, E. Employment impact of Covid-19 crisis: from short term effects to long terms prospects. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 47, 391–410 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-020-00168-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-020-00168-5