Highlights

-

NiCo-LDHs successfully grow in situ on rod-like ZnO with unique structures.

-

The interface of NiCo@C and rod-like ZnO result in interfacial polarization.

-

The RLmin of NiCo@C/ZnO reaches − 60.97 dB with the EABmax of 6.08 GHz.

-

The excellent performance comes from the effect of dielectric loss and magnetic loss.

Abstract

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) have a special structure and atom composition, which are expected to be an excellent electromagnetic wave (EMW) absorber. However, it is still a problem that obtaining excellent EMW-absorbing materials from LDHs. Herein, we designed heterostructure NiCo-LDHs@ZnO nanorod and then subsequent heat treating to derive NiCo@C/ZnO composites. Finally, with the synergy of excellent dielectric loss and magnetic loss, an outstanding absorption performance could be achieved with the reflection loss of − 60.97 dB at the matching thickness of 2.3 mm, and the widest absorption bandwidth of 6.08 GHz was realized at 2.0 mm. Moreover, this research work provides a reference for the development and utilization of LDHs materials in the field of microwave absorption materials and can also provide ideas for the design of layered structural absorbers.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Nowadays, electromagnetic waves (EMW) are currently used in a wide range of medical and military equipment as a medium for the wireless control and transmission of information in electronic devices [1,2,3]. However, the failure of electronic facilities, human organ damage and other negative effects caused by electromagnetic pollution deserve our attention [4, 5]. In order to make better prevention of EMW, EMW-absorbing materials that can attenuate EMW energy and convert incident EMW into heat or otherwise forms of energy have been designed and developed [6, 7]. The idealized absorbing material should meet the requirement of wide bandwidth, light weight and thin thickness [8,9,10]. However, the EMW absorption capacity of a single material is relatively weak. Therefore, the development of composites that gratify the demands will become the focus of future studies.

Many suitable absorbers have been developed, such as carbon materials [11], alloys [12], transition metal oxides/sulfides/selenides [13,14,15], and MXene [16]. With the development of technology, the requirements for the EMW absorption properties and the condition of using EMW-absorbing materials are become more and more stringent. So, it is necessary to develop better materials to meet the requirements of practical application. At this point, metal alloys came into the research range due to excellent permittivity and permeability, with NiCo alloys being the most notable [17, 18]. NiCo alloys possess the characteristics of high-temperature calcination resistance, oxidation resistance, corrosion resistance, and easy extraction [19, 20], and are widely used in high-tech fields such as aerospace.

Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) are a new type of material formed by the self-assembly of metal cations with organic ligands, which have the advantages of large surface area, low density, and high porosity [21,22,23,24]. However, individual MOFs have not yet been extensively applied in EMW-absorbing materials as a result of poor dielectric properties [25]. Therefore, many attempts have been made to tune the electromagnetic properties of MOF materials and derivatives to obtain satisfactory EMW absorption performance. The most popular approach is introducing other metal cations to modulate the morphology and elemental composition of MOFs and derivatives [26, 27]. Che et al. [28] prepared Ni/C/ZnO microspheres with yolk-shell structure based on bimetallic NiZn-MOFs. Zhou et al. [29] prepared CoZn-MOFs as templates to prepare rod-shaped Co/ZnO/C composites, all of which can obtain excellent EMW-absorbing properties. However, there are still some difficulties, such as complicated preparation process and poor attenuation performance, etc. Therefore, it is still necessary to find other ideas to obtain ideal EMW-absorbing materials [30,31,32].

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) are compounds consisting of positively charged lamellae and interlayer anions interacting with each other [33,34,35]. Generally, the most common methods for generating LDHs include hydrothermal method, ion exchange method, co-precipitation method, and so on [36, 37]. Metallic alloys are acquired via high-temperature calcination of LDHs materials in an inert gas environment, which is one of the methods to attain polymetallic alloys. The method is an important way to access excellent electromagnetic absorbing materials and make the electromagnetic parameters of the alloys controllable [38, 39]. Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a semiconductor material with a wide band gap and excellent dielectric properties, which, together with its ease of making unique structures, makes ZnO promising for development as dielectric material [40, 41].

In this paper, we presented a novel design that exploits the synergistic effect between components, which to develop electromagnetic absorbing materials that can meet practical needs. Hence, NiCo@C/ZnO composites decorated with NiCo alloy particles were synthesized through hydrothermal method and annealing process, which demonstrated excellent EMW absorption performance. The minimum reflection loss (RLmin) value was − 60.97 dB with thickness of 2.3 mm, and the maximum effective absorption bandwidth (EABmax) value was 6.08 GHz with thickness of 2.0 mm. In addition, the electromagnetic absorption mechanism of NiCo@C/ZnO composites was discussed in detail. This work not only provides ideas for the development and utilization of MOFs materials, but also serves references for the design of new electromagnetic absorbing materials.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Chemical Reagents

All chemicals were of analytical grade (AR) and used directly without any further purification. Cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, AR, 99%), nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O AR, 99%), ammonia solution (NH3·H2O, 28%), Zinc acetate (Zn(CH3COO)2, AR, 99–101%), 2-methlimidazole (C4H6N2, 98%, 2-MIM), hexamethylene tetramine (C6H12N4), absolute ethanol (C2H6OH), and methyl alcohol (CH3OH, 99.5%). They are purchased from Chemical Reagents Company Limited of China Pharmaceutical Group. Deionized water was used throughout the experiment.

2.2 Sample Preparation

2.2.1 Preparation of Rod-Like ZnO

As shown in Scheme 1, zinc acetate and hexamethylenetetramine were added to 50 mL of deionized water at the ratio of 1:1 and stirred with a glass rod until the particles were completely dissolved. The pH of the mixed solution was adjusted to pH = 10 with ammonia and stirred continuously at room temperature for about 3 h. The solution was transferred to 100 mL of PTFE liner and kept at 90 °C for 12 h. Finally, after cooling to room temperature, the sample was dried at 60 °C after washing with deionized water and ethanol. The rod-like ZnO materials were defined as S-1.

2.2.2 Preparation of NiCo@C Composites

0.5 g of Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.5 g of Ni(NO3)3·6H2O were added to 40 mL of methanol solution which was recorded as solution A. 8 mmol of 2-methylimidazole (2-MIM) was dissolved in 20 mL of methanol solution and stirred until the pellet was completely dissolved, which was recorded as solution B. Then, solution B was quickly poured into solution A, and stirred continuously at room temperature for 2 h. Then, the solution was transferred to a 100 mL PTFE liner and maintained at 160 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting material is washed several times with deionized water and ethanol and then dried at 60 °C. The samples were denoted as S-2. The material was calcined at 400 °C for 3 h under argon atmosphere at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The obtained composites were designated as S-3.

2.2.3 Preparation of Rod-Like Structured NiCo@C/ZnO Composites

Typically, 1.0 g of rod-like ZnO material is added to 40 mL methanol and stirred to obtain a homogeneous solution. 0.5 g of Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.5 g of Ni(NO3)3·6H2O were joined in the mixed solution. Then 8 mmol of 2-Methylimidazole (2-MIM) was dissolved in 20 mL of methanol solution with stirring until the pellet was fully dissolved. The 2-methylimidazole solution was quickly poured into a methanolic solution containing rod-like ZnO materials and stirred continuously for 2 h at room temperature. Then, the solution was transferred to a 100 mL PTFE liner and maintained at 160 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting material is washed several times with deionized water and ethanol and then dried at 60 °C. The samples were denoted as S-4. Finally, the composites were calcinated at 400 °C under Ar atmosphere and Air atmosphere with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1 for 3 h. The as-obtained composites were named as S-5 and S-6, respectively.

2.3 Characterization

The crystalline structures of samples were obtained on powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV with Cu-Ka radiation (λ = 0.15418)). The morphology of samples was characterized by a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, JFOL JSM-7800F) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrum. The crystal structure and microstructure of samples were recorded by a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100). Raman shift of samples was collected through using a Renishaw in Via Plus Micro-Raman spectroscopy system with a 50-mW laser at 532 mm. The bond states of surface elements for samples were tested by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) on Thermo Fisher ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer with an Al Ka X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of samples was recorded by an SDT Q600 analyzer from room temperature to 900 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under Ar atmosphere.

2.4 Electromagnetic Parameters

Based on the mass ratio of 1:2, the composites and paraffin are mixed evenly, and pressed into a ring sample to be tested, in which the inner diameter, outer diameter, and thickness are 3.04, 7.00, and 2.00 mm, respectively. The EM parameters were obtained by a vector network analyzer (N5234A, Agilent, USA) using a coaxial method in the frequency range of 2.0–18.0 GHz. Using transmission line theory is to work out the reflection loss (RL) values of absorbers at different thicknesses in their corresponding frequency [42, 43].

where c, f and d refer to the light speed, the corresponding frequency and the matching thickness, Zin is the normalized input impedance and the Z0 means the impedance of free space, \(\varepsilon_{r}\) and \(\mu_{r}\) are the complex permittivity and complex permeability, respectively. Normally, when RL < − 10 dB, it means that the absorbing material will absorb more than 90% of the incident EMW.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Composition and Structure

The crystal structures of all samples were analyzed by XRD. As displayed in Fig. 1, the curve of S-1 shows the XRD pattern of rod-like ZnO with characteristic peaks of 31.8°, 34.4°, 36.3°, 47.5°, 56.6°, and 62.9°, 66.4°, assigning to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), and (103), (200) of ZnO crystal planes. There are obvious characteristic peaks on the curve of S-2, where the characteristic peaks at 11.3°, 22.6°, 33.9°, 38.1° and 60.1° conform to the (003), (006), (100), (015), and (110) crystal planes of NiCo-LDHs, respectively [44]. The characteristic peaks corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) crystals of Ni are 44.6°, 51.8° and 75.9°on the curves belonging to S-3 (PDF No. 4-0850). However, compared with the standard cards Co (PDF No. 15-0806) and Ni (PDF No. 4-0850), the position of the characteristic peak is somewhat shifted, which proves that the nickel–cobalt alloy is formed instead of a single metal. In Fig. S1, in addition to the characteristic peaks of NiCo alloys, characteristic peaks attributed to amorphous C can also be seen [11, 12], proving that NiCo@C can be obtained from NiCo-LDHs composites through high-temperature calcination in Ar. In the XRD spectrum of S-4, the characteristic peaks of NiCo-LDHs can be seen in addition to those of ZnO, which suggest the successful preparation of NiCo-LDHs@ZnO composites. NiCo@C/ZnO composites obtained via calcination of NiCo-LDHs@ZnO composites under Ar atmosphere are evidenced by the distinct peaks of ZnO and NiCo alloys in the XRD spectrum of S-5. The XRD spectrum of S-6 provides characteristic peaks of ZnO and Co2NiO4 from Co2NiO4@ZnO composites. No significant characteristic peaks of impurities were found in all the XRD patterns, confirming the high purity of the prepared samples. Figure 1b shows the Raman spectra of S-1, S-3, and S-5. The characteristic peak of ZnO (437 cm−1) appears on the curve of S-1. The characteristic peak of NiCo (534 cm−1) and obvious D/G peaks were noted in S-3, where the ID/IG value was 0.95, which proves that graphitic carbon is produced during calcination at high temperatures. NiCo/C composites are favorable for the formation of conductive networks and the construction of heterogeneous interfaces. S-5 has both characteristic peaks of NiCo alloy, ZnO and obvious D/G peaks, in which the ID/IG value does not change, and this conclusion is also consistent with the XRD results.

The SEM images reveal the external morphology and elemental distribution of the sample. Figure 2a gives an SEM image of ZnO, which has a relatively homogeneous morphology and is not connected to each other. The cross section of the rod-shaped ZnO is ortho-hexagonal as seen in Fig. 2a-1. SEM image of NiCo-LDHs (S-2) (Fig. 1b) indicates the flower-like structures of NiCo-LDHs generated by stacking multiple lamellar structures, in which the size of each nanosheet is greater than 1 μm. It can be seen from the elemental distribution map of S-2 that the elements O, Ni and Co are uniformly dispersed in the NiCo-LDHs. The comparison of SEM images of S-2 (Fig. 2b) with S-3 (Fig. 2c) demonstrates no significant change in the overall morphology after high temperature annealing under Ar atmosphere, it underwent a transition from NiCo-LDH to NiCo@C, which led to the thinning of the nanosheets in S-3, the EDS spectrum (Fig. S2) indicate that this material is composed of three elements: nickel, cobalt and carbon, and their mass percentages are 38.42%, 33.96%, and 27.63%, respectively. In the SEM image of NiCo-LDHs@ZnO (S-4) (Fig. 2d), the surface of rod-like ZnO is covered with many layers of NiCo-LDHs and the layers are closely aligned. Zn elements are relatively concentrated, while Ni and Co elements are mainly scattered around the rod-like ZnO in the elemental distribution diagram. In Fig. 2e, the NiCo@C/ZnO composite (S-5) obtained after calcination at high temperature has a significantly lower number of layers coated on the rod-like ZnO. In the elemental distribution diagram (Figs. 2i and S3b), the distribution of Zn elements does not change obviously, while the distribution of Ni and Co elements becomes more dispersed and found that the contents of C, O, Ni, Co, and Zn were 15.03%, 14.43%, 14.76%, 11.92%, and 43.85% (Fig. S3b), respectively. The size of the layered structure of S-6 decreases significantly, but the number of layers remains almost unchanged (Fig. 2f).

The TEM images allow further to observe and analyze the internal structure and material composition of the prepared samples (Fig. 3). The rod-like ZnO exhibits a diameter of approximately 500 nm with no connections among themselves (Fig. 3a), which is consistent with observation in the SEM images (Fig. 2a). The lattice spacing (d) observed in the HR-TEM image of ZnO is 0.266 nm, matching the (002) crystal plane of ZnO (Fig. 3a-1). In Fig. 3a-2, the spots are uniformly dispersed and distributed in order, demonstrating the single-crystal hexagonal structure of ZnO. The layered structure overlying the rod structure can still be visualized in Fig. 3b, with the shaded part of the figure shows the NiCo-LDHs overlying the rod-like ZnO. The lattice with a spacing of 0.262 nm in Fig. 3b-1 corresponds to the (012) crystal plane of NiCo-LDHs [45]. The observed circle points to the (107) crystal plane of NiCo-LDHs in high-resolution TEM images of S-4 (Fig. 3b-2,). The lamellar structure changes in size and number after high-temperature annealing (Fig. 3c), and a number of grains (NiCo alloy) can also be observed. Besides, the lattice spacing of 0.204 nm (Fig. 3c-1) matches (111) plane of the NiCo alloy, which also confirms the formation of NiCo alloy [46, 47]. The diffraction rings in Fig. 3c-2 are attributed to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) crystal planes of the NiCo alloy, which are in accordance with the results of other characterizations.

In order to further analyze the weight variation trend of the samples during calcination, TGA measurements were made in Ar atmosphere at a temperature increasing rate of 10 °C min−1 from room temperature to 900 °C. In Fig. S4, the mass of S-4 decreased slightly before 200 °C by about 0.99%, which is due to the gradual evaporation of the water contained in the sample with the increase in temperature. From 200 to 720 °C, the mass of the sample decreases linearly with the increase in temperature, and the final mass decreases to 13.05%, which was due to the gradual decomposition of NiCo-LDHs into NiCo@C composites with the increase in temperature. From the full-scan XPS spectrum (Fig. 4a), there are five characteristic peaks in S-5, which belong to C 1 s, Zn 2p, O 1 s, Co 2p, and Ni 2p, respectively. In the high-resolution spectra in C1 s (Fig. 4b), the characteristic peaks located at 284.6, 286.5, and 288.5 eV ascribed to C–C/C=C, C–O, and C–C=O, respectively [48]. From the high-resolution spectra of Zn 2p (Fig. 4c), the characteristic peak at 1021.4 eV corresponds to Zn 2p3/2 and the characteristic peak at 1044.6 eV corresponds to Zn 2p1/2. On the high-resolution spectrum of O 1 s of S-5 (Fig. 4d), three characteristic peaks of 531.5, 530.6, and 529.0 eV can be observed, corresponding to the water or O adsorbed on the sample surface, oxygen vacancies and metal-O (Ni–O/Co–O) respectively [49, 50]. Co 2p can be fitted to six distinct characteristic peaks (Fig. 4e), the characteristic peaks at 779.2 and 795.4 eV ascribed to metal-Co, and the characteristic peak at 780.6 and 796.3 eV can match the Co–O bond. The remaining characteristic peaks at 788.3 and 803.4 eV can be matched to the satellite peaks [51, 52]. In the Ni 2p high-resolution XPS spectrum of S-5 (Fig. 4f), the peaks at 878.9 and 860.8 eV are attributed to satellite peaks, and the peaks at 870.1 and 855.2 eV can be ascribed to the Ni–O bond. The O in the Co–O and Ni–O bond may originate from the surface oxidation of NiCo alloy when exposed to air. The characteristic peaks at 871.5 and 853.6 eV can be matched to the metal Ni in NiCo alloy [53, 54].

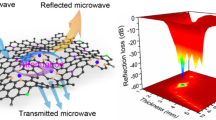

3.2 Electromagnetic Performance and Parameter

According to Eqs. 1 and 2, we can calculate the relationship between the thickness of the corresponding EMW-absorbing material and the reflection loss (RL) in the range of 2–18 GHz frequency. The RLmin value is a key index to evaluate the performance of EMW-absorbing materials. Figures 5 and 6 show 3D and 2D reflection loss diagrams of frequency and thickness correspondence for all samples in the 2–18 GHz range. The RLmin value of S-1 is − 49.01 dB, corresponding to a thickness of 9.8 mm (Fig. 5a), and the EABmax values reaches 3.36 GHz at 5.2 mm (Fig. 6a), which means the EMW absorption of S-1 performance is not ideal. Figures 5b and 6b present the EMW-absorbing performance of S-2. However, the RLmin value of − 16.05 dB and the EABmax value of 1.04 GHz indicate that the EMW-absorbing performance of the NiCo-LDHs material also fail to meet the requirements. The corresponding RLmin value of S-3, at a thickness of 4.5 mm, is − 41.46 dB and the EABmax values, at a thickness of 5.1 mm, is 4.0 GHz; the reason is that NiCo-LDH is transformed into NiCo@C composite by high-temperature annealing, which not only facilitates the construction of conductive network, but also the magnetic loss generated by NiCo alloy can improve the electromagnetic performance. In contrast, after plating the NiCo-LDHs on the surface of rod ZnO, the performance of S-4 has changed not much compared with S-1, the RLmin value of S-4 at 9.9 mm is − 46.51 dB, and the EABmax value is 3.20 GHz, which corresponds to the thickness of 5.3 mm.

Figures 5e-f and 6e-f correspond to S-5 and S-6 obtained from calcining S-4 in different atmospheres, respectively. The results showed that the absorption properties of the products obtained by annealing in different inert atmospheres differed significantly. As compared to S-4, the EMW-absorbing performance of S-6 is slightly improved, and the RLmin value drops sharply at a thickness of 7.8 mm is − 43.75 dB, and the EABmax value reaches 4.24 GHz at the thickness of 7.1 mm. However, the EMW absorption performance of S-5 is significantly increased. The RLmin value has reached − 60.97 dB, but the matching thickness is 2.3 mm. The EABmax value has reached 6.08 GHz, and the matching thickness is only 2.0 mm. This is because the formation of NiCo@C composites makes significant changes in the structure of S-5, the increase in layer spacing makes the reflection and scattering of incident EMW more frequently, and the appearance of NiCo@C composites particles also promotes the polarization loss of incident EMW.

3.3 Microwave Absorption and Mechanism

The EM wave absorption characteristics of samples is usually analyzed according to the complex permittivity (εr = ε′ − jε″) and the complex permeability (μr = μ′ − jμ″) [55]. As shown in Fig. 7a, the real part of complex permittivity for S-5 is larger than that of other samples, and the ε′ value decreases gradually from 8.7 to 7.0 with the increase in frequency. It has typical dielectric response characteristics [56]. The ε′ values of S-1 and S-4 gradually increase with the increase in frequency, which is associated with the presence of ZnO. The ε′ values of S-2 and S-3 do not change significantly with frequency, but S-3 shows a significantly improvement than S-2. This is due to weak dielectric loss of NiCo-LDHs and NiCo alloy, which also proves that high-temperature calcination can significantly improve their dielectric properties. In addition, it can also be observed in Fig. 7b-c that the sample has multiple fluctuations at high-frequency bands, which implies that there is a significant polarization loss during the attenuation of the incident EMW, which could be due to the interfacial polarization caused by charge accumulation on heterogeneous junction surfaces and the dipole polarization occurring on defects or functional groups of materials. Both polarizations increase the dielectric loss capacity of the absorber [57, 58]. The curves of μ′ and μ″ versus frequency of all samples (Fig. 7d-e) were observed. A similar trend can be observed for all materials except for S-6, indicating poor magnetic properties. The μ′ values of all these materials occur in the range of 4–7 GHz. In general, the large fluctuations in the low-frequency band indicate the presence of natural resonance behavior, while fluctuations in the high-frequency band are attributed to exchange resonance, which contribute magnetic loss for the microwave-absorbing material [59, 60].

Debye relaxation is an important way for absorbing materials to have dielectric loss. It can usually be deduced by Eqs. 3 and 4 to obtain Eq. 5, which can express relationship between ε′ and ε″ [61, 62].

where τ stands for polarization relaxation time, εs for static permittivity, and ε∞ points to the high-frequency limited permittivity. As shown in Fig. 8a, more semicircles can be observed in the Cole–Cole diagram of S-5, which implies that more relaxation processes occur in S-5, related to the interface between ZnO@C and ZnO. The presence of a variable number of semicircles in other samples can also be seen in Fig. S5, which proves that the Debye relaxation process is prevalent in the prepared material [63]. According to the transmission line theory, the attenuation constant (α) can be calculated by Eq. 6 to reflect the attenuation ability of the absorbing material. Figure 8b is the correlation curve between attenuation coefficients and frequencies of all samples. With increasing frequency, all the curves show a significant change, but the attenuation system of S-5 is more prominent than that of other samples, which means that S-5 has a stronger attenuation ability to the incident EMW and shows better absorption performance, which conforms to our previous conclusion [64].

where d denotes the thickness of the absorber and μ0 means vacuum permeability. The relationship between C0 value and frequency can be used to analyze the mechanism of magnetic loss. When eddy current loss occurs inside the absorbing material, the C0 value will not change significantly with the change of frequency [65]. Figure 8c is the correlation curve between C0 and the frequency of all samples. As the frequency increases, the C0 value of S-6 does not change much, which indicates that the magnetic loss caused by eddy current loss plays a dominant role, while the other samples have two larger fluctuating peaks at 4–7 and 12–14 GHz, representing natural resonance and exchange resonance respectively. This is consistent with our previous analysis. In the range of 8–11 and 14–18 GHz, the variation of C0 value is quite small, which indicates that the eddy current loss plays a greater role in the attenuation of electromagnetic waves in this frequency range.

In addition to the attenuation coefficient, impedance matching (\(\left| {Z_{{{\text{in}}}} /Z_{0} } \right|\)) is a critical factor to determine the absorption performance of EMW--absorbing materials. According to Eq. 7, we can get the relationship between \(\left| {Z_{{{\text{in}}}} /Z_{0} } \right|\) and frequency of different samples. Generally, the closer the \(\left| {Z_{{{\text{in}}}} /Z_{0} } \right|\) value of the EMW-absorbing material is to 1, the EMW materials will absorb EM more easily [66], and the absorbing material will show better EMW absorption performance. From Fig. 8d, it can be found that the curve of S-5 is closer to 1, which matches its excellent EMW-absorbing performance. The impedance matching values of other materials vary greatly, which means that their impedance matching performance is poor, giving rise to poor EMW absorption performance [67].

Scheme 2 shows a possible EMW absorption mechanism for S-5, which implies that the excellent absorption performance comes as a result of multiple mechanisms. Due to the large specific surface area of the composite material, it is easy to form a conductive network, which is conducive to induced current transmission under the action of the external magnetic field, causing the internal electrons to undergo directional migration and converting electromagnetic energy into thermal energy [68, 69]. On the one hand, the incident EMW that can enter the material is reflected and scattered, with large amount of EMW attenuating in the process [70]. Secondly, due to the different layered media between NiCo alloy and rod-like ZnO, electrons will accumulate on the contact interface, leading to interface polarization, which is an important reason for the excellent dielectric parameters of S-5 [71, 72]. Thirdly, the presence of NiCo@C composites and O vacancies cause dipole polarization in face of an external magnetic field, which promotes the loss of incident EMW. Furthermore, the eddy current loss and resonance loss caused by the presence of NiCo alloy are main sources of the magnetic loss [73]. In addition, as shown in Table 1, the composite absorber prepared in this study has better overall absorption performance than other composites.

4 Conclusion

In summary, we obtained NiCo-LDHs@ZnO composites through a reasonable combination of NiCo-LDHs with rod-like ZnO through simple experiments, and the final NiCo@C/ZnO composites were obtained after calcination and had excellent EMW absorption properties. The RLmin value reached − 60.97 dB at the matching thickness of 2.3 mm, and the EABmax value is 6.08 GHz when the matching thickness is 2.0 mm. The interaction of dielectric and magnetic losses is the main reason for the excellent attenuation properties of EMW. This work provides an idea for further expanding the application of LDHs in absorbent materials and provides a method for preparing hetero-structured absorbent materials.

References

M. Cao, X. Wang, M. Zhang, J. Shu, W. Cao et al., Electromagnetic response and energy conversion for functions and devices in low-dimensional materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29(25), 1807398 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201807398

F. Zhang, Z. Jia, Z. Wang, C. Zhang, B. Wang et al., Tailoring nanoparticles composites derived from metal-organic framework as electromagnetic wave absorber. Mater. Today Phys. 20, 100475 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2021.100475

C. Liang, P. Song, H. Qiu, Y. Zhang, X. Ma et al., Constructing interconnected spherical hollow conductive networks in silver platelets/reduced graphene oxide foam/epoxy nanocomposites for superior electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. Nanoscale 11, 22590–22598 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NR06022G

H. Lv, Z. Yang, B. Liu, G. Wu, Z. Lou et al., A flexible electromagnetic wave-electricity harvester. Nat. Commun. 12, 834 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21103-9

Y. Zhang, K. Ruan, X. Shi, H. Qiu, Y. Pan et al., Ti3C2Tx/rGO porous composite films with superior electromagnetic interference shielding performances. Carbon 175, 271–280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2020.12.084

H. Zhang, Z. Jia, A. Feng, Z. Zhou, C. Zhang et al., Enhanced microwave absorption performance of sulfur-doped hollow carbon microspheres with mesoporous shell as a broadband absorber. Compos. Commun. 19, 42–50 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2020.02.010

G. Ma, L. Xia, H. Yang, X. Wang, T. Zhang et al., Multifunctional lithium aluminosilicate/CNT composite for gas filtration and electromagnetic wave absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 418, 129429 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.129429

C. Zhang, S. Yin, C. Long, B. Dong, D. He et al., Hybrid metamaterial absorber for ultra-low and dual-broadband absorption. Opt. Exp. 29(9), 14078 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.423245

Z. Gao, Z. Jia, K. Wang, X. Liu, L. Bi et al., Simultaneous enhancement of recoverable energy density and efficiency of lead-free relaxor-ferroelectric BNT-based ceramics. Chem. Eng. J. 402, 125951 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.125951

H. Lv, X. Zhou, G. Wu, U. Karaa, X. Wang, Engineering defects in 2D g-C3N4 for wideband, efficient electromagnetic absorption at elevated temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TA02785A

G. Liu, C. Wu, L. Hu, X. Hu, X. Zhang et al., Anisotropy engineering of metal organic framework derivatives for effective electromagnetic wave absorption. Carbon 181, 48–57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021.05.015

L. Wang, M. Huang, X. Yu, W. You, J. Zhang et al., MOF-derived Ni1-xCox@Carbon with tunable nano-microstructure as lightweight and highly efficient electromagnetic wave absorber. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 150 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00488-0

X. Zhou, Z. Jia, X. Zhang, B. Wang, X. Liu et al., Electromagnetic wave absorption performance of NiCo2X4 (X=O, S, Se, Te) spinel structures. Chem. Eng. J. 420, 129907 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.129907

J. Zhao, J. Zhang, L. Wang, J. Li, T. Feng et al., Superior wave-absorbing performances of silicone rubber composites via introducing covalently bonded SnO2@MWCNT absorbent with encapsulation structure. Compos. Commun. 22, 100486 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2020.100486

X. Zhu, Y. Dong, Z. Xiang, L. Cai, F. Pan et al., Morphology-controllable synthesis of polyurethane-derived highly cross-linked 3D networks for multifunctional and efficient electromagnetic wave absorption. Carbon 182, 254–264 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021.06.028

T. Hou, Z. Jia, B. Wang, H. Li, X. Liu et al., MXene-based accordion 2D hybrid structure with Co9S8/C/Ti3C2Tx as efficient electromagnetic wave absorber. Chem. Eng. J. 414, 128875 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.128875

P. Liu, S. Gao, Y. Wang, Y. Huang, Y. Wang et al., Core-shell CoNi@graphitic carbon decorated on B, N-Co doped hollow carbon polyhedrons toward lightweight and high-efficiency microwave attenuation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(28), 25624–25635 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b08525

S. Hu, Y. Zhou, M. He, Q. Liao, H. Yang et al., Hollow Ni-Co layered double hydroxides-derived NiCo-alloy@g-C3N4 microtubule with high performance microwave absorption. Mater. Lett. 231, 171–174 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2018.08.048

L. Wang, B. Wen, X. Bai, C. Liu, H. Yang, NiCo alloy/carbon nanorods decorated with carbon nanotubes for microwave absorption. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2(12), 7827–7838 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.9b01842

H. Sun, C. Tian, Y. Li, J. Wu, Q. Wang et al., Coupling NiCo alloy and CeO2 to enhance electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution in alkaline solution. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 4(11), 2000122 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adsu.202000122

X. Gao, Z. Jia, B. Wang, X. Wu, T. Sun et al., Synthesis of NiCo-LDH/MXene hybrids with abundant heterojunction surfaces as a lightweight electromagnetic wave absorber. Chem. Eng. J. 419, 130019 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130019

Z. Zhang, Z. Cai, Z. Wang, Y. Peng, L. Xia et al., A review on metal-organic framework derived porous carbon-based novel microwave absorption materials. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 56 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00582-3

W. Cheng, Y. Wang, S. Ge, X. Ding, Z. Cui et al., One-step microwave hydrothermal preparation of Cd/Zr-bimetallic metal-organic frameworks for enhanced photochemical properties. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 4, 150–161 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-020-00199-5

T. Hou, Z. Jia, B. Wang, H. Li, X. Liu et al., Metal-organic framework-derived NiSe2-CoSe2@C/Ti3C2Tx composites as electromagnetic wave absorbers. Chem. Eng. J. 422, 130079 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130079

P. Liu, S. Gao, Y. Wang, F. Zhou, Y. Huang et al., Metal-organic polymer coordination materials derived Co/N-doped porous carbon composites for frequency-selective microwave absorption. Compos. Part B 202, 108406 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108406

B. Zhong, L. Zhang, J. Yu, K. Fan, Ultrafine iron-cobalt nanoparticles embedded in nitrogen-doped porous carbon matrix for oxygen reduction reaction and zinc-air batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 546, 113–121 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2019.03.038

Y. Wang, S. Yang, H. Wang, G. Wang, X. Sun et al., Hollow porous CoNi/C composite nanomaterials derived from MOFs for efficient and lightweight electromagnetic wave absorber. Carbon 167, 485–494 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2020.06.014

L. Wang, X. Yu, X. Li, J. Zhang, M. Wang et al., MOF-derived yolk-shell Ni@C@ZnO schottky contact structure for enhanced microwave absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 383, 123099 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123099

Q. Liao, M. He, Y. Zhou, S. Nie, Y. Wang et al., Highly cuboid-shape heterobimetallic metal–organic frameworks derived from porous Co/ZnO/C microrods with improved electromagnetic wave absorption capabilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 10(34), 29136–29144 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b09093

M. Kong, Z. Jia, B. Wang, J. Dou, X. Liu et al., Construction of metal-organic framework derived Co/ZnO/Ti3C2Tx composites for excellent microwave absorption. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 26, e00219 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2020.e00219

L. Wang, X. Shi, J. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Gu, Lightweight and robust rGO/sugarcane derived hybrid carbon foams with outstanding EMI shielding performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 52, 119–126 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.03.029

Z. Jia, Z. Gao, K. Kou, A. Feng, C. Zhang et al., Facile synthesis of hierarchical a-site cation deficiency perovskite LaxFeO3-y/RGO for high efficiency microwave absorption. Compos. Commun. 20, 100344 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2020.04.010

L. Cao, J. Wang, D. Zhong, T. Lu, Template-directed synthesis of sulphur doped NiCoFe layered double hydroxide porous nanosheets with enhanced electrocatalytic activity for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 6(7), 3224–3232 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA09734D

F. Zhu, W. Liu, Y. Liu, W. Shi, Construction of porous interface on CNTs@NiCo-LDH core-shell nanotube arrays for supercapacitor applications. Chem. Eng. J. 383, 123150 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123150

R. Zhang, R. Zhu, Y. Li, Z. Hui, Y. Song et al., CoP and Ni2P implanted in hollow porous N-doped carbon polyhedron for pH universal hydrogen evolution reaction and alkaline overall water splitting. Nanoscale 12(46), 23851–23858 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NR07126A

X. Kong, B. Xia, Y. Xiao, H. Chen, H. Li et al., Regulation of Cobalt-Nickel LDHs’ structure and components for optimizing the performance of electrochemical sensor. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2(10), 6387–6396 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.9b01370

Y. Dou, J. Zhou, F. Yang, M. Zhao, Z. Nie et al., Hierarchically structured Layered-double-hydroxide@Zeolitic-imidazolate-framework derivatives for high-performance electrochemical energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 4(32), 12526–12134 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6TA04765C

Y. Xie, C. Feng, Y. Guo, S. Li, C. Guo et al., MOFs derived carbon nanotubes coated CoNi alloy nanocomposites with N-doped rich-defect and abundant cavity structure as efficient trifunctional electrocatalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 53, 147786 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147786

J. Kang, H. Zhang, X. Duan, H. Sun, X. Tan et al., Magnetic Ni-Co alloy encapsulated N-doped carbon nanotubes for catalytic membrane degradation of emerging contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 362, 251–261 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.035

J. Wang, B. Wang, Z. Wang, L. Chen, C. Gao et al., Synthesis of 3D flower-like ZnO/ZnCo2O4 composites with the heterogeneous interface for excellent electromagnetic wave absorption properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 586, 479–490 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2020.10.111

Y. Dong, X. Zhu, F. Pan, B. Deng, Z. Liu et al., Mace-like carbon fiber/ZnO nanorod composite derived from typha orientalis for lightweight and high-efficient electromagnetic wave absorber. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-021-00277-2

M. Qin, L. Zhang, X. Zhao, H. Wu, Defect induced polarization loss in multi-shelled spinel hollow spheres for electromagnetic wave absorption application. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004640 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202004640

X. Zhou, Z. Jia, A. Feng, K. Wang, X. Liu et al., Dependency of tunable electromagnetic wave absorption performance on morphology-controlled 3D porous carbon fabricated by biomass. Compos. Commun. 21, 100404 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2020.100404

H. Li, Q. Jin, J. Zhao, B. Wang, X. Guo, Rational synthesis of ZIF-67@Co-Ni LDHs heterostructure and derived heterogeneous carbon-based framework as high-efficient multifunctional sulfur host. Dalton. Trans. 49(36), 12686–12694 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/D0DT02442B

Y. Liu, Y. Wang, C. Shi, Y. Chen, D. Li et al., Co-ZIF derived porous NiCo-LDH nanosheets/N doped carbon foam for high performance supercapacitor. Carbon 165, 129–138 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2020.04.084

X. Zhou, Z. Jia, X. Zhang, B. Wang, W. Wu et al., Controllable synthesis of Ni/NiO@porous carbon hybrid composites towards remarkable electromagnetic wave absorption and wide absorption bandwidth. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 87, 120–132 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.01.073

X. Liang, Z. Man, B. Quan, J. Zheng, W. Gu et al., Environment-stable CoxNiy encapsulation in stacked porous carbon nanosheets for enhanced microwave absorption. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 102 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00432-2

H. Yan, X. Dai, K. Ruan, S. Zhang, X. Shi et al., Flexible thermally conductive and electrically insulating silicone rubber composite films with BNNS@Al2O3 fillers. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 4, 36–50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-021-00208-1

T. Hou, Z. Jia, A. Feng, Z. Zhou, X. Liu et al., Hierarchical composite of biomass derived magnetic carbon framework and phytic acid doped polyanilne with prominent electromagnetic wave absorption capacity. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 68, 61–69 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.06.046

J. Zhao, J. Zhang, L. Wang, S. Lyu, W. Ye et al., Fabrication and investigation on ternary heterogeneous MWCNT@TiO2-C fillers and their silicone rubber wave-absorbing composites. Compos. Part A 129, 105714 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.105714

Q. Chang, H. Liang, B. Shi, H. Wu, Sodium oxalate-induced hydrothermal synthesis of wood-texture-column-like NiCo2O4 with broad bandwidth electromagnetic wave absorption performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 600, 49–57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.05.019

X. Zhang, J. Zhu, P. Yin, A. Guo, A. Huang et al., Tunable high-performance microwave absorption of Co1-xS hollow spheres constructed by nanosheets within ultralow filler loading. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(49), 1800761 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201800761

S. Gao, G. Zhang, Y. Wang, X. Han, Y. Huang et al., MOFs derived magnetic porous carbon microspheres constructed by core-shell Ni@C with high-performance microwave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 88, 56–65 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.02.011

B. Zhao, Y. Li, X. Guo, R. Zhang, J. Zhang et al., Enhanced electromagnetic wave absorbing nickel (oxide)-carbon nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 45(18), 24474–24486 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.08.173

M. Green, Z. Liu, R. Smedley, H. Nawaz, X. Li et al., Graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for microwave absorption. Mater. Today Phys. 5, 78–86 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2018.06.005

S. Dong, W. Zhang, X. Zhang, P. Hu, J. Han, Designable synthesis of core-shell SiCw@C heterostructures with thickness-dependent electromagnetic wave absorption between the whole X-band and Ku-band. Chem. Eng. J. 354, 767–776 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.062

H. Zhang, Z. Jia, B. Wang, X. Wu, T. Sun et al., Construction of remarkable electromagnetic wave absorber from heterogeneous structure of Co-CoFe2O4@mesoporous hollow carbon spheres. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 129960 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.129960

F. Pan, Z. Liu, B. Deng, Y. Dong, X. Zhu et al., Lotus leaf-derived gradient hierarchical porous C/MoS2 morphology genetic composites with wideband and tunable electromagnetic absorption performance. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00568-1

M. Green, J. Xu, H. Liu, J. Zhao, K. Li et al., Terahertz absorption of hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Today Phys. 4, 64–69 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2018.04.001

G. He, Y. Duan, H. Pang, Microwave absorption of crystalline Fe/MnO@C nanocapsules embedded in amorphous carbon. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 57 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-0388-4

Z. Lou, C. Yuan, Y. Zhang, Y. Li, J. Cai et al., Synthesis of porous carbon matrix with inlaid Fe3C/Fe3O4 micro-particles as an effective electromagnetic wave absorber from natural wood shavings. J. Alloy Compd. 775, 800–809 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.10.213

Z. Gao, Z. Zhao, D. Lan, K. Kou, J. Zhang et al., Accessory ligand strategies for hexacyanometallate networks deriving perovskite polycrystalline electromagnetic absorbents. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 82, 69–79 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.11.071

H. Lv, Y. Li, Z. Jia, L. Wang, X. Guo et al., Exceptionally porous three-dimensional architectural nanostructure derived from CNTs/graphene aerogel towards the ultra-wideband EM absorption. Compos. Part B 196, 108122 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108122

J. Xu, L. Xia, J. Luo, S. Lu, X. Huang et al., High-performance electromagnetic wave absorbing CNT/SiCf composites: synthesis, tuning, and mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 20775–20784 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b19281

X. Zhang, X. Zhang, D. Wang, H. Yuan, S. Zhang et al., Three-dimensional graphene-supported nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube architecture for attenuation of electromagnetic energy. J. Mater. Chem. C 7(38), 11868–11878 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TC04191E

G. Liu, J. Tu, C. Wu, Y. Fu, C. Chu et al., High-yield two-dimensional metal-organic framework derivatives for wideband electromagnetic wave absorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 20459–20466 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c00281

D. Zhang, H. Zhang, J. Cheng, H. Raza, T. Liu et al., Customizing coaxial stacking VS2 nanosheets for dual-band microwave absorption with superior performance in the C- and Ku-bands. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 5923–5933 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/D0TC00763C

D. Lan, Z. Gao, Z. Zhao, K. Kou, H. Wu, Application progress of conductive conjugated polymers in electromagnetic wave absorbing composites. Comp. Commun. 26, 100767 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2021.100767

H. Lv, C. Wu, F. Qin, H. Peng, M. Yan, Extra-wide bandwidth via complementary exchange resonance and dielectric polarization of sandwiched FeNi@SnO2 nanosheets for electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 90, 1–8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.12.083

M. Xu, J. Liu, H. Zhang, Y. Zhang, X. Wu et al., Electrically conductive Ti3C2Tx MXene/polypropylene nanocomposites with an ultralow percolation threshold for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60, 4342–4350 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.1c00320

Z. Wang, L. Yang, Y. Zhou, C. Xu, M. Yan et al., NiFe LDH/MXene derivatives interconnected with carbon fabric for flexible electromagnetic wave absorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 16713–16721 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c05007

M. Qin, L. Zhang, X. Zhao, H. Wu, Lightweight Ni foam-based ultra-broadband electromagnetic wave absorber. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202103436

L. Liang, Q. Li, X. Yan, Y. Feng, Y. Wang et al., Multifunctional magnetic Ti3C2Tx MXene/graphene aerogel with superior electromagnetic wave absorption performance. ACS Nano 15, 6622–6632 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c09982

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51407134), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2019YQ24), Taishan Scholars and Young Experts Program of Shandong Province (No. tsqn202103057), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2016M590619) and the Qingchuang Talents Induction Program of Shandong Higher Education Institution (Research and Innovation Team of Structural-Functional Polymer Composites). The authors acknowledge the support from The Thousand Talents Plan, The World-Class University and Discipline, The Taishan Scholar’s Advantageous and Distinctive Discipline Program of Shandong Province and The World-Class Discipline Program of Shandong Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Jia, Z., Liu, X. et al. Construction of 1D Heterostructure NiCo@C/ZnO Nanorod with Enhanced Microwave Absorption. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 175 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00704-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00704-5