Abstract

This paper provides an analysis of Balassa’s ‘revealed comparative advantage’ (RCA). It shows that when using RCA, it should be adjusted such that it becomes symmetric around its neutral value. The proposed adjusted index is called ‘revealed symmetric comparative advantage’ (RSCA). The theoretical discussion focuses on the properties of RSCA and empirical evidence, based on the Jarque–Bera test for normality of the regression error terms, using both the RCA and RSCA indices. We compare RSCA to other measures of international trade specialization including the Michaely index, the Contribution to Trade Balance, Chi Square, and Bowen’s Net Trade Index. The result of the analysis is that RSCA—on balance—is the best measure of comparative advantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A fuller discussion of this topic is present in Sect. 3.

In the remainder of the paper we work with 22 countries since we do not have complete data for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Korea, Mexico and Poland for the entire time-period.

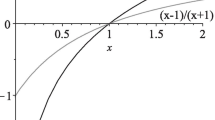

Another and very similar measure to the RSCA has been applied by Hariolf Grupp in various publications (see e.g., Grupp 1994, 1998) in the context of technological specialization. RPA or Revealed Patent Advantage can be defined as:

RPA ij = (RTA 2 − 1)/(RTA 2 + 1) × 100, where RTA is Revealed Technological Advantage, calculated similar to RCA (see Eq. 1) but based on US patent data.

It can be argued that e.g. the relative strength of the Danish shipyards is, at least partially, due to the strength of the shipping industry (and perhaps vice versa) (see, Linder 1961; Andersen et al. 1981; Fagerberg 1995). However, it would be difficult to argue that Denmark has no comparative advantage in building ships and boats given the high level of exports from this sector.

The problem—as mentioned earlier—is that the χ2 measure takes high values both if a country is (much) more specialized in a sector, and if a country is (much) less specialized in a sector.

The years: 1988–1991; 1991–1994; 1994–1997; 1997–2000; 2000–2003; and 2003–2006.

References

Amable, B. (2000). International specialisation and growth. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 11, 413–431.

Amendola, G., Guerrieri, P., & Padoan, P. C. (1992). International patterns of technological accumulation and trade. Journal of International and Comparative Economics, 1, 173–197.

Amighini, A., Leone, M., & Rabellotti, R. (2011). Persistence versus change in the international specialization pattern of Italy: how much does the ‘District Effect’ matter? Regional Studies, 45, 381–401.

Amiti, M. (1999). Specialization patterns in Europe. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 135, 573–593.

Andersen, E. S., Dalum, B., & Villumsen, G. (1981). The importance of the home market for the technological development and the export specialization of manufacturing industry, IKE Seminar. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press.

Aquino, A. (1981). Change over time in the pattern of comparative advantage in manufactured goods: an empirical analysis for the period 1972–1974. European Economic Review, 15, 41–62.

Archibugi, D., & Pianta, M. (1992). The technological specialisation of advanced countries. A report to the EEC on international science and technology activities. Dortrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Archibugi, D., & Pianta, M. (1994). Aggregate convergence and sectoral specialization in innovation. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 4, 17–33.

Balassa, B. (1965). Trade liberalization and ‘revealed’ comparative advantage. The Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, 32, 99–123.

Ballance, R., Forstner, H., & Murray, T. (1985). On measuring revealed comparative advantage: a note on Bowen’s indices. Weltwirtschaftliches Arhiv, 121, 346–350.

Bowen, H. P. (1983). On the theoretical interpretation of trade intensity and revealed comparative advantage. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 119, 464–472.

Cantwell, J. (1989). Technological innovation and multinational corporations. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cantwell, J. (1995). The globalisation of technology: what remains of the product cycle model? Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19, 155–174.

CEPII (1983). Economie Mondiale: la montée des tension (Paris).

Crafts, N. F. R., & Thomas, M. (1986). Comparative advantage in UK manufacturing trade, 1910–1935. Economic Journal, 96, 629–645.

D’Agostino, L. M., Laursen, K., & Santangelo, G. D. (2013). The impact of R&D offshoring on the home knowledge production of OECD investing regions. Journal of Economic Geography, 13, 145–175.

Dalum, B., Laursen, K., & Verspagen, B. (1999). Does specialization matter for growth? Industrial and Corporate Change, 8, 267–288.

Dalum, B., Laursen, K., & Villumsen, G. (1998). Structural change in oecd export specialisation patterns: de-specialisation and ‘Stickiness’. International Review of Applied Economics, 12, 447–467.

De Benedictis, L., Gallegati, M., & Tamberi, M. (2008). Semiparametric analysis of the specialization-income relationship. Applied Economics Letters, 15, 301–306.

Dosi, G., & Nelson, R. R. (2013). The evolution of technologies: an assessment of the state-of-the-art. Eurasian Business Review, 3, 3–46.

Dosi, G., Pavitt, K. L. R., & Soete, L. L. G. (1990). The economics of technical change and international trade. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Fagerberg, J. (1995). User-producer interaction, learning and comparative advantage. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19, 243–256.

Fagerberg, J. (1997). Competitiveness, scale and R&D. In J. Fagerberg, L. Lundberg, P. Hansson, & A. Melchior (Eds.), Technology and international trade. Cheltenham, UK and Lyme, US: Edward Elgar.

Grupp, H. (1994). The measurement of technical performance of innovations by technometrics and its impact on established technology indicators. Research Policy, 23, 175–193.

Grupp, H. (1998). Foundations of the economics of innovation. Cheltenham, UK and Lyme, US: Edward Elgar.

Guerrieri, P. (1997). The changing world trade environment, technological capability and the competitiveness of the European Industry, paper presented at the Conference on Trade, Economic Integration and Social Coherence, Vienna, Austria, January.

Hausmann, R., & Hidalgo, C. (2011). The network structure of economic output. Journal of Economic Growth, 16, 309–342.

Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabási, A.-L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space conditions the development of nations. Science, 317, 482–487.

Hinloopen, J., & van Marrewijk, C. (2008). Empirical relevance of the Hillman condition for revealed comparative advantage: 10 stylized facts. Applied Economics, 40, 2313–2328.

Iapadre, P. L. (2001). Measuring international specialization. International Advances in Economic Research, 7, 173–183.

Kol, J., & Mennes, L. B. M. (1985). Intra-industry specialization: some observations on concepts and measurement. International Journal of Economics, 21, 173–181.

Krugman, P. (1987). The narrow moving band, the Dutch disease, and the competitive consequences of Mrs. Thatcher: notes on trade in the presence of dynamic scale economies. Journal of Development Economics, 27, 41–55.

Laursen, K. (2000a). Trade specialisation, technology and growth: theory and evidence from advanced countries. Cheltenham, UK and Lyme, US: Edward Elgar.

Laursen, K. (2000b). Do export and technological specialisation patterns co-evolve in terms of convergence or divergence?: evidence from 19 OECD Countries, 1971–1991. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 10, 415–436.

Laursen, K., & Drejer, I. (1999). Do inter-sectoral linkages matter for international export specialisation? The Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 8, 311–330.

Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2005). The fruits of intellectual production: economic and scientific specialisation among OECD countries. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29, 289–308.

Liegsalz, J., & Wagner, S. (2013). Patent examination at the State Intellectual Property Office in China. Research Policy, 42, 552–563.

Linder, S. B. (1961). An essay on trade and transformation. Stockholm: Almquist and Wiksell.

Malerba, F., & Montobbio, F. (2003). Exploring factors affecting international technological specialization: the role of knowledge flows and the structure of innovative activity. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 13, 411–434.

Meliciani, V. (2002). The impact of technological specialisation on national performance in a balance-of-payments-constrained growth model. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 13, 101–118.

Michaely, M. (1962/67). Concentration in international trade. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

OECD. (2011). Globalisation, comparative advantage and the changing dynamics of trade. Paris: OECD.

Soete, L. L. G. (1981). A general test of the technological gap trade theory. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 117, 638–666.

Soete, L. L. G. (1987). The impact of technological innovation on international trade patterns: the evidence reconsidered. Research Policy, 16, 101–130.

Soete, L. G., & Wyatt, S. E. (1983). The use of foreign patenting as an internationally comparable science and technology output indicator. Scientometrics, 5, 31–54.

UNIDO (1986). International comparative advantage in manufacturing: changing profiles of resources and trade, Unido publication sales no. E86 II B9. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

van Hulst, N., Mulder, R., & Soete, L. L. G. (1991). Exports and technology in manufacturing industry. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 127, 246–264.

Vollrath, T. L. (1991). A theoretical evaluation of alternative trade intensity measures of revealed comparative advantage. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 127, 265–280.

Webster, A., & Gilroy, M. (1995). Labour skills and the UK’s comparative advantage with its European Union partners. Applied Economics, 27, 327–342.

World Bank (1994). China: foreign trade reform, country study series. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Yeats, A. J. (1985). On the appropriate interpretation of the revealed comparative advantage index: implications of a methodology based on industry sector analysis. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 121, 61–73.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper draws on Laursen (2000a). The author thanks Mario Pianta for the suggestion to write a paper on this topic, and two reviewers for this journal for excellent comments and suggestions for improvements. The usual caveats apply.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laursen, K. Revealed comparative advantage and the alternatives as measures of international specialization. Eurasian Bus Rev 5, 99–115 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-015-0017-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-015-0017-1