Abstract

Background

The condition of blood vessel network in the retina is an essential part of diagnosing various problems associated with eyes, such as diabetic retinopathy.

Methods

In this study, an automatic retinal vessel segmentation utilising fuzzy c-means clustering and level sets is proposed. Retinal images are contrast-enhanced utilising contrast limited adaptive histogram equalisation while the noise is reduced by using mathematical morphology followed by matched filtering steps that use Gabor and Frangi filters to enhance the blood vessel network prior to clustering. A genetic algorithm enhanced spatial fuzzy c-means method is then utilised for extracting an initial blood vessel network, with the segmentation further refined by using an integrated level set approach.

Results

The proposed method is validated by using publicly accessible digital retinal images for vessel extraction, structured analysis of the retina and Child Heart and Health Study in England (CHASE_DB1) datasets. These datasets are commonly used for benchmarking the accuracy of retinal vessel segmentation methods where it was shown to achieve a mean accuracy of 0.961, 0.951 and 0.939, respectively.

Conclusion

The proposed segmentation method was able to achieve comparable accuracy to other methods while being very close to the manual segmentation provided by the second observer in all datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

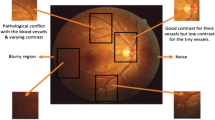

Utilising computer-assisted diagnosis of retinal fundus images is becoming an alternative to manual inspection of the fundus by a specialist, known as direct ophthalmoscopy. Moreover, computer-assisted diagnosis of retinal fundus images was shown to be as reliable as direct ophthalmoscopy and requires less time to be processed and analysed. Various eye related pathologies that can result in blindness, such as macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy are routinely diagnosed by utilising retinal fundus images [1]. One of the fundamental steps in diagnosing diabetic retinopathy is the extraction of retinal blood vessels from fundus images. Although several segmentation methods have been proposed, this segmentation remains challenging due to variations in retinal vasculature network and image quality. Currently, the main challenges in retinal vessel segmentation are the noise (often due to uneven illumination) and thin vessels. Furthermore, the majority of the proposed segmentation methods focus on optimising the preprocessing and vessel segmentation parameters separately for each dataset. Hence, these approaches can often achieve high accuracy for the optimised dataset, whereas if applied to other datasets the accuracy will be reduced. Although vessel segmentation methods usually contain preprocessing steps aimed at enhancing the appearance of vessels, some approaches skip the preprocessing steps and start with the segmentation step.

Nowadays, many segmentation methods rely on machine learning concepts combined with traditional segmentation techniques for enhancing the segmentation accuracy of their method by providing a statistical analysis of the data to support segmentation algorithms. These machine learning concepts can be broadly categorised into unsupervised and supervised approaches, based on the use of labelled training data. In a supervised approach, each pixel in the image is labelled and assigned to a class by a human operator, i.e., vessel and non-vessel. A series of feature vectors is generated from the data being processed (pixel-wise features in image segmentation problems) and a classifier is trained by using the labels assigned to the data. In an unsupervised approach, predefined feature vectors without any class labels are used where similar samples are gathered in distinct classes. This clustering is based on some assumptions about the structure of the input data, i.e., two classes of input data where the feature vectors of each class are similar to each other (vessel and not vessel). Based on the problem, this similarity metric can be complex or defined by a simple metric such as pixel intensities.

In this manuscript, a brief discussion of retinal vessel segmentation methods is given to provide some insight into different methods and is by no means an exhaustive review of these methods. For a detailed discussion on different vessel segmentation methods please refer to [2]. Niemeijer et al. [3] proposed a supervised retina vessel segmentation where a k-nearest neighbour (k-NN) classifier was utilised for identifying vessel and non-vessel pixels by using a feature vector constructed based on a multi-scale Gaussian filter. Staal et al. [4] proposed a similar approach that utilised a feature vector constructed by using a ridge detector. Based on a feature vector constructed by using multi-scale Gabor wavelet filters, Soares et al. [5] proposed the use of a Bayesian classifier for segmenting vessel and non-vessel pixels. Marín et al. [6] proposed a neural network (NN) based classifier by utilizing calculated feature that use moment-invariant features. Retinal vessel segmentation by using a classifier based on boosted decision trees was proposed by Fraz et al. [7]. Meanwhile Ricci and Perfetti [8] proposed a classifier by utilising a support vector machine coupled with features derived that used a rotation-invariant linear operator.

The main advantage of using an unsupervised segmentation approach as compared to a supervised approach is its independence from a labelled training data. This can be considered as an important aspect in medical imaging and related applications that often contain large data. It would be a tedious task for medical experts to manually label different structures inside the datasets. Popular unsupervised retinal vessel segmentation methods can be categorised as vessel tracking, matched filtering and morphology-based methods. Starting from a set of initial points defined either manually or automatically, vessel tracking methods try to segment the vessels by tracking the centre line of the vessels. This tracking can be done by utilising different vessel estimation profiles, such as Gaussian [9], generic parametric [10], Bayesian probabilistic [11] and multi-scale profiles [12]. One of the earliest examples of vessel tracking based vessel segmentation methods was proposed by Yin et al. [13] based on the maximum a posteriori (MAP) technique. Initial seeding positions corresponding to centreline and vessel edges were determined by using statistical analysis of intensity and vessel continuity properties. Vessel boundaries were then estimated by using a Gaussian curve fitting function applied to the vessel cross-section intensity profile. Zhang et al. [14] proposed a similar approach by combining MAP technique with a multi-scale line detection algorithm where their method was able to handle vessel tree branching and crossover points with good performance.

Based on the notion that the vessel profile could be modelled by using a kernel (structuring element), filtering concepts try to model and segment the vessels by convolving the retinal image with a 2D rotating template. A rotating template is used to approximate the vessel profile in as many orientations as possible (known as the filter response) with the response being the highest in places where the vessels fit the kernel. Techniques based on filtering utilise different kernels for modelling and enhancing retinal vessels, such as matched filters [15], Gaussian filters [16], wavelet filters [17, 18], Gabor filters [5] and COSFIRE filters [19, 20]. Methods utilising morphological operations can be used to enhance retinal images for use with other segmentation methods or for segmenting blood vessels from the background [21]. Recently, deformable model-based segmentation (i.e., level sets and active contours) have been receiving interest for retinal vessel segmentation [22,23,24,25,26]. Chaudhuri et al. [27] proposed one of the earliest examples of filtering based retina vessel segmentation methods where the vessel profile was modelled by using 12 templates. Wang et al. [18] later expanded the method proposed by using multi-wavelet kernels [27], resulting in a higher segmentation accuracy. Kovacs et al. [28] proposed the use of Gabor filters for segmenting vessels combined with contour reconstruction techniques. Kande et al. [29] proposed a vessel segmentation method by using a spatially weighted fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm where matched filtering was used for enhancing retinal vessels.

Considered as one of the fundamental concepts in image processing, mathematical morphology could be used anywhere, from image enhancement to segmentation. Although mathematical morphology is primarily used for retinal vessel enhancement, it can also be used for vessels segmentation. Fraz et al. [30] proposed the use of first-order derivative of a Gaussian filter for initial enhancement of retinal vessel centrelines, followed by a multi-directional morphological Top-hat transform for segmenting the vessels. BahadarKhan et al. [31] proposed Generalised Linear Model (GLM) and Frangi filters for enhancing the vessels in retinal images combined with Moment-Preserving thresholding for segmenting vessels. Sigurosson et al. [32] proposed a hybrid method by using a path opening filter, followed by a fuzzy set theory based data fusion approach, and their proposed method was able to achieve good segmentation accuracy in thinner vessels. Roychowdhury et al. [33] proposed an adaptive global thresholding method using a novel stepping criteria for retinal vessel segmentation with promising results in segmenting thin vessels. Mapayi et al. [34] proposed an approach that use CLAHE based vessel enhancement and a global image thresholding method by applying phase congruency for segmenting vessels in retinal images. Mapayi et al. [35] proposed by use of energy feature computed through gray level co-occurrence matrix for adaptively thresholding the vessels in retinal images that can be used for vessel segmentation in the green channel or grayscale retinal images.

Currently, machine learning algorithms are often utilised as supportive tools to automate and/or to enhance most segmentation methods by providing statistical analysis on a set of data generated by other segmentation methods. Therefore, any existing unsupervised segmentation algorithm could be enhanced by employing and integrating machine learning concepts. Complex segmentation tasks and problems are usually solved by using a whole pipeline of several segmentation algorithms belonging to various image processing concepts. In this study, an automated vessel extraction method in retinal fundus images based on a hybrid technique, comprising of genetic algorithm enhanced spatial fuzzy c-means algorithm with integrated level set method evaluated on real-world clinical data is proposed. Furthermore, a combination of filters is utilised to enhance the segmentation as each filter responded in a distinct way to different pixels in the image. Considering the different image characteristics between datasets, the segmentation approach can be made more robust by combining filters. As the aim of this study is to propose an optimal segmentation method for use on various datasets, the proposed method was not optimised for any specific dataset. The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Sect. 2 outlines the proposed method and datasets, the performance of the proposed method is discussed in Sect. 3 and conclusions are drawn in Sect. 4.

2 Materials and Methods

In this study, the green channel of the RGB fundus image was utilised as it has been shown that vessels have the highest contrast against the background in the green channel while the use of blue channel results in a small dynamic range and red channel offers insufficient contrast, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Moreover, Mendonca and Campilho [36] further validated the usefulness of the green channel by comparing different channels of RGB image, Luminance channel of National Television Systems Committee (NTSC) colour space and ‘a’ component of the “lab” image representation system where the green channel of RGB image was shown to have better overall contrast. Furthermore, like most other studies, only the pixels inside the field of view (FOV) of the image is considered for the segmentation because the pixels outside this area are considered as background and have no known medical application. Figure 2 illustrates the flowchart of the proposed method. These steps are discussed in detail in the following sections.

2.1 Dataset

Publicly accessible digital retinal images for vessel extraction (DRIVE) [4], structured analysis of the retina (STARE) [37] and Child Heart and Health Study in England (CHASE_DB1) CHASE_DB1 [38] datasets used in this study are amongst the most popular datasets used for developing and testing the performance of various retinal segmentation methods. Datasets used also provide corresponding vessel segmentations manually done by different experts and are considered as the ground truth segmentation.

DRIVE dataset includes 40 colour fundus images that were equally divided into training and testing sets. For each image in the dataset, a FOV mask along with manual expert segmentation of the corresponding vessel tree (one expert for the training set and two experts for the testing set) were provided. A Canon CR5 non-mydriatic camera with a FOV of 45° and bit-depth of 8-bit was used to capture the images with a resolution of 768 × 584 pixels. Figure 3 illustrates an image from the test set with its respective manual vessel segmentation.

STARE dataset includes 20 colour fundus images with half of them containing signs of different pathologies. For each image in the dataset, manual segmentation of corresponding vessel tree done by two experts are provided. A canon TopCon TRV-50 fundus camera with FOV of 35° and bit-depth of 8-bit was used to capture the images with a resolution of 700 × 605 pixels. Figure 4 illustrates an image from this dataset with its respective manual vessel segmentation.

CHASE_DB1 dataset includes 28 color fundus images from patients participated in the child heart and health study in England. For each image in the dataset, manual segmentation of corresponding vessel tree done by two experts are provided. A Nidek NM 200D fundus camera with FOV of 30 degrees and bit-depth of 8-bit was used to capture the images with a resolution of 1280 × 960 pixels. Figure 5 illustrates an image from this dataset with its respective manual vessel segmentation.

As seen from the sample images, the ground truth segmentation can be considered highly subjective as the manual segmentation provided by the first observer in DRIVE and CHASE_DB1 datasets includes finer segmentation for thinner vessels in contrast to STARE dataset where the manual segmentation provided by the second observer includes the finer segmentation.

2.2 Performance Measures

True positive (TP) denotes vessel pixels correctly segmented as vessel pixels while true negative (TN) denotes non-vessel pixels correctly segmented as non-vessel pixels. False positive (FP) denotes non-vessel pixels segmented as vessel pixels, while false negative (FN) denotes vessel pixels segmented as non-vessel pixels.

Sensitivity represents the probability that the segmentation method will correctly identify vessel pixels and is computed by:

Specificity is the probability that the segmentation method will correctly identify non-vessel pixels. Specificity is computed by:

Accuracy represents the overall performance of a segmentation method and is computed by:

The area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, also known as AUC shows the performance of the segmentation and is determined based on the combination of sensitivity and specificity. In this study AUC was calculated by the following formula [39,40,41]:

It should be noted that an AUC of 0.50 or less means that the segmentation is purely based on random guessing and is not useful while an AUC of 1 means that the segmentation algorithm is able to segment all pixels correctly.

2.3 Preprocessing

The extracted green band from the original fundus image was first filtered by using a 3 × 3 median filter to reduce the image noise. As retina fundus images show high contrast around the edges of the image resulting in false positive vessels being detected around the edges of the image and the edges are smoothed by using the method proposed by [19]. Initial FOV mask was computed by thresholding the luminance channel on CIElab colour space [42] calculated from the original RGB fundus image. Then, the mask was dilated by one pixel iteratively where the value of the new pixel was calculated as the mean value of its 8-connected neighbouring pixels. This process was repeated 50 times to ensure that no false vessels will be detected near the FOV border.

Then, contrast limited adaptive histogram equalisation (CLAHE) algorithm [43] was used to enhance the contrast between vessels and background with the clip limit empirically set at 0.0023. CLAHE improves the local contrast by not over amplifying the noise present in relatively homogeneous regions and was used in many retina vessel segmentation methods. Next, the noise was suppressed by having the images opened morphologically by using a circular structuring element with a radius of 8 pixels. Finally, the image was further enhanced by using a combination of Top-hat and Bottom-hat morphological operations as illustrated in Fig. 6.

A sample image from the DRIVE dataset with different preprocessing steps illustrated. a Color fundus image, b CIElab color space luminance channel, c FOV mask, d RGB color space green channel, e image after median and morphological filtering, f morphological Top-hat, g morphological Bottom-hat and h image after morphological filtering

2.3.1 Gabor Filtering

For enhancing the small vessels inside the image, a Gabor wavelet-based filter was used. For 2D images (spatial Gabor filter), convolution was used for applying Gabor’s filters where varying kernels were defined as Gaussian kernels modulated by a sinusoid [44]. By using a Cartesian basis as the centre, these kernels were defined based on an abscissa with orientation θ. Gaussian and sinusoid components of the Gabor’s filter \(K_{\theta , \sigma , \gamma , \lambda , \varphi }\) can be independently customised:

where, the Gaussian component was customised by its deviation σ and a spatial aspect ratio γ defining the ellipticity of the circular Gaussian and the sinusoid was customised by a spatial wavelength λ and a phase offset ϕ. The Gabor’s kernel was expressed by using the orientation θ, and with a change of both scale defined by the size of pixel (vx, vy) and by a translation of the centre of the kernel (ic,jc):

where

A Gabor kernel was made of parallel stripes with different weights, inside an ellipsoidal envelope with the kernel parameters controlling the size, orientation, the position of these stripes. The wavelength λ, specified in pixels, represented the wavelength of the filter. This value was used in scaling the stripes, whereas by modifying the wavelength, the overall sizes of the stripes were modified with the stripes kept at the same orientation and relative dimensions. This wavelength should be more than 2 and was often chosen to be less than the fifth of the image dimension (because of the influence of image borders). The angle of the parallel stripes was specified by using the orientation θ. By modifying θ, the kernel can be rotated and oriented at the desired position. The shift of the cosine factor was represented by the phase offset ϕ. The symmetry of the kernel was determined by ϕ, whereas by modifying the shift, positions of the inhibitory and excitatory stripes were changed. The kernel was symmetric for a phase shift of ϕ = 0 and asymmetric for a phase shift of ϕ = π/4. Ellipticity was represented by using the aspect ratio γ. For a ratio of 1, the support is circular, whereas larger ratio results in smaller but higher (number of) stripes and a smaller ratio results in longer strips. The bandwidth b was used as a replacement for the Gaussian deviation σ by analogy to the animal visual system [45]. After the Gabor filtering, the image background was computed and removed by subtracting the filtered image from the median filtered image with a large kernel, followed by morphological Top-hat filtering for enhancing the vessel structure by using a circular structuring element with aradius of 8 pixels.

2.3.2 Frangi Filtering

Frangi filters [46] were first proposed for use in coronary artery segmentation by enhancing the vessel profiles. Hessian matrix based Frangi filter is a popular approach that is both efficient and requires less computation time [47]. The Hessian matrix is constructed by computing the vertical and horizontal diagonals of the images second order derivative. The Hessian-based vessel-ness filter can be defined as:

where the pixel of interest is defined by x, the standard deviation for computing the Gaussian derivative of the image is denoted as σ and f represents the filter. The hessian matrix can be defined as:

where Hxx, Hxy, Hyx and Hyy represent the images directional second-order partial derivatives. Let’s denote λ1 and λ2 as the eigenvalues of H where they are used for determining the probability of the pixel of interest x being a vessel based on the following notions:

Then, the Hessian-based Frangi filter can be defined as:

where \(R_{b} \;{\text{and}}\; a\) are used for differentiating linear structures from blob like structures, while β and S are being used for differentiating background and vessels with the controlling parameters set empirically (α = 0.9, \(\beta = 13\), \(\sigma = \{ 1, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, \ldots ,4\}\). The smoothing parameter σ was chosen to be varied from 1 to 4 in increments of 0.1 as it provided the best overall vessel enhancement. Selecting a small σ value will lose some thicker vessel details, whereas selecting a fixed large σ value will lose thinner vessel details. By varying the smoothing parameter σ and retaining the maximum pixel value from different scales, it is ensured that the vessels are enhanced and details are kept as much as possible. Figure 7 illustrates the vessel enhancement resulting from different values of σ on a sample image and Fig. 8 shows the matched filtering steps and their effect on the image.

2.4 Fuzzy Clustering

Fuzzy set theorem, introduced by Zadeh [48] and its adaptation for image processing by Bezdek [49] is one of the most used and researched image segmentation algorithms. In this study, soft clustering (fuzzy c-means) was used as each pixel can belong to many clusters based on a membership degree, resulting in better performance in images with poor contrast, region overlapping and inhomogeneity of region contrasts, as compared to hard clustering (k-means) where each pixel belongs to a single cluster. The use of clustering-based machine learning method was proposed as it was not dependent on the labelled training data. In clustering-based machine learning methods, there is only one set of feature vectors without any class labelling as these approaches gather similar samples in clusters. As traditional fuzzy c-means (FCM) algorithm, where clustering is only based on image intensities is very sensitive to noise, and the addition of spatial relations between pixels was proposed by many researchers to improve the performance [50, 51].

2.4.1 Fuzzy c-Means Algorithm

As a fuzzy clustering method, fuzzy c-means algorithm was based on the representation of clusters by their respective centres by minimising a quadratic centre. The data space X = {x1, x2,…,xN} can be clustered by minimising the objective function J with respect to cluster centres (ci) and membership matrix u by:

Based on the following constraints:

where U = [uij]C×N represents the matrix for membership function, d(xj, ci) is the matrix representing the distance between \(x_{j}\) and cluster center \(c_{i}\), C represents the number of clusters, N is the number of data points in search space and M represents the fitness degree where (m > 1). Equation (10) can be solved by converting to an unconstraint problem by Lagrange multiplier. Membership degree and cluster centres were calculated by using an alternating calculation as they cannot be simultaneously calculated. Convergence was achieved by alternatively fixing the classes and calculating the membership function, followed by fixing the membership function and calculating the cluster centres. Algorithm 1 represents the pseudo code for FCM clustering.

In the case of image segmentation, the gray value of the pixel I is represented by xi, N represents the total number of pixels, the number of clusters (regions) is represented by C, distance between cluster centre cj and pixel xi is represented by d2(xi, cj) and the membership degree between pixel xi and cluster \(c_{j}\) is represented by uij.

2.4.2 Fuzzy c-Means Algorithm Enhanced with Genetic Algorithm

The main disadvantage of the FCM algorithm is its intendancy to get trapped in local minima, metaheuristic approaches, such as genetic algorithms (GA), tabu search (TS), simulated annealing (SA), ant colony based optimisation (ACO) and their hybrids were proposed by many researchers to overcome this limitation [51,52,53,54]. Metaheuristics can perform well on noisy images and the initial solutions from them are often very close to optimal cluster centres [55]. Inspired by the evolution theory and natural selection, genetic optimisation was proposed by Srinivas [56], it is a population-based stochastic optimisation algorithm where each chromosome can represent a solution with a sequence of genes representing cluster centres in FCM. Each successive population is created based on survival and reproduction of the fittest chromosomes based on a fitness function with a termination criterion based on the number of iterations or reaching an optimised fitness function [57]. In order to produce the initial population P, FCM is run n times, producing a chromosome of size C (number of clusters). Afterward, the fittest chromosomes were selected based on:

Where, f represents the fitness, \(J\) is the objective function (Eq. 10) and k is a constant (set as 1) where maximisation of the fitness function f results in minimisation of the objective function \(J\). A proportional selection algorithm known as the Roulette Wheel selection was applied afterward to determine the number of copies of a chromosome going into mutation and crossover pool:

Each chromosome was then crossed with a single point crossover with a fixed probability of μc and then fitness values were recalculated with FCM the method. Each chromosome then mutated with a very small probability \(\mu_{m}\). A random number δ ∊ [0, 1] was then generated and the chromosome was mutated by:

where v represents a specific the gene in the chromosome. Stopping criterion can be based on the following conditions:

-

(1)

If after nerp iterations, no significant improvement is achieved in the objective function.

-

(2)

Number of the iterations reaching maximum nbmaxiter.

As discussed earlier, incorporation of spatial features of the image in the FCM algorithm is crucial to achieve a good accuracy in complicated images. Ahmad et al. [52] proposed a new constrained objective function as:

Chen et al. [50] later proposed an update to the Eq. (15), replacing it with:

With cluster center and membership degrees calculated by:

where \(\bar{x}\) is the filtered image \(x\), NR and xr represent the cardinality and neighborhood of the neighbors of pixel \(x_{j}\) and α controls the effect of the neighborhood term.

2.5 Level Set Refinement

Contrary to methods where pixels are clustered for segmentation, level sets rely on boundary tracking by dynamic variations. Unlike active contours where a parametric characterisation of contours is utilised, level set methods embed them as a time-dependent partial differential equation (PDE) function \({\emptyset }\left( {t,x,y} \right)\) [58]. Let us denote an image I on domain Ω with C representing a closed curve and its zero level set description as:

The goal is matching the interior to the ROI and exterior to the background by evolving the curve C. To represent the interior of curve C, a smoothed Heaviside step function \(H_{\varepsilon } \left( \emptyset \right)\) is utilised while the exterior of the curve C is calculated by \((1 - H_{\varepsilon } \left( \emptyset \right))\) as:

whereas the area adjacent to the curve C is represented by a smoothed Dirac function δɛ as:

The evolution of \(\emptyset\) can be resolved by:

where the normal direction is denoted by \(\left| {\nabla \emptyset } \right|\), the initial contour is \(\emptyset_{0} \left( {x,y} \right)\) and the comprehensive forces including internal (interface geometry) and external (image gradient) forces are denoted by F [58]. To stop the level set evolution near-optimal solution, an edge indication function g is utilised for regulating the force F:

where I represent the image, Gσis the Gaussian smoothing kernel and ∇ represents image gradient operation. It should be noted that function g is near zero in variation boundaries otherwise it is a positive value. The overall level set segmentation can be represented as:

where mean curvature is approximated as \({\text{div}}\left( {{{\nabla \emptyset } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\nabla \emptyset } {\left| {\nabla \emptyset } \right|}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left| {\nabla \emptyset } \right|}}} \right)\) and v represents a customised balloon force. As regular level set converts a 2D image into a 3D segmentation problem, grid space and time step should comply with the Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) condition [58] and many other constraints. An updated level set segmentation can be given as [59]:

where \(\zeta \left( \emptyset \right)\) incorporates image gradient and \(\xi \left( \emptyset \right)\) denotes the Dirac function. Individual contributions of these terms are controlled by constants λ, v and \(\mu.\) Leveraging the FCM clustering, an approximation of extracted contours in regions of interest can be used for determining the controlling parameters for initialisation and evolution of level sets [59]. Let’s assume that the region of interest in clustered FCM is \(R_{k} :\left\{ {r_{k} = \mu_{nk} , n = x \times N_{y} + y} \right\}\) and then the level set function \(\emptyset_{0} \left( {x,y} \right)\) can be initiated with a binary image \(B_{K}\) obtained from thresholding Rk with b0(∊(0, 1)) as \(B_{K} = R_{K} \ge b_{0}.\)

As there are several parameters to control the level set evolution, it is desired to approximate them as best as possible for an accurate segmentation with several rules proposed for this approximation. A larger time step τ accelerates the level set evolution in the expense of possible boundary leaks, less detailed but smoother segmentation can be achieved by a larger value of \(G_{\sigma }\) and for a stable level set evolution(τ × μ) < 0.25 is desired. Although the specific adaptation of these parameters for each image is desired, it is practically infeasible to manually adjust these values in medical imaging. However, based on the initial level set function \(\emptyset_{0}\) obtained from FCM clustering, these values can be estimated on each specific image. Initially, the length l and area α are calculated by:

Heaviside function \(H\left( {\emptyset_{0} } \right)\) is defined as:

As the initial level set function \(\emptyset_{0}\) can approximate the true boundaries closely, it is possible to take a conservative \(\lambda\). Remaining variable will be set as:

In the formulation of the standard level set, the direction of evolution is determined by balloon force v, the positive values of v lead to shrinking and negative values lead to expansion. Taken as a constant, larger value of v leads to faster evolutions but slower evolutions are preferable near the object boundaries. Being constant, a decision has to be made on the selection of a positive or a negative value as it can affect the final segmentation dramatically. By utilising the initial FCM clustering, it is possible to adjust the direction and magnitude of balloon force on a pixel specific level by taking the degree of membership (or \(P_{i}^{L }\)) of each pixel as an indicator of distance of the pixel μk to the component of interest \(R_{k}\), leading to a slower evolution and a faster evolution with \(\emptyset\) being near or far from the true border, respectively. The enhanced balloon force matrix G(Rk)( ∊ [ − 1, 1]) is represented as:

Based on Eqs. (32), (27) can be rewritten as:

With the balloon force derived, the level set will be slow near object boundary and will become dependent on smoothing function without the need for any manual interventions. There might be small blob-like regions comprised of unconnected pixels wrongly identified as vessels in retinal images due to noise or anatomical structures. As a result, the segmented image is post-processed by removing blob-like and unconnected regions, containing less than 30 pixels. Figure 9 illustrates the proposed segmentation on a sample image from the DRIVE dataset.

3 Results and Discussion

In this study, similar to the majority of other studies, the proposed method was compared to the ground truth segmentations provided by the first observer (mentioned as the first expert in some publications) in CHASE_DB1 and STARE datasets and the test set of the DRIVE dataset. Since CHASE_DB1 and STARE datasets do not provide the FOV masks and to make the proposed method compatible with other datasets, FOV mask in this study was automatically generated and no FOV masks supplied in datasets were used in this study. All experiments were done by using MATLAB 2013a on an HP ProBook (2.3 GHz Intel Core i5 Processor, 4 GB RAM). Table 1 demonstrates the performance of the proposed method as compared to the most recent segmentation methods for STARE and DRIVE datasets, while Table 2 shows a comparison of the proposed method and other state-of-the-art segmentation techniques in the CHASE_DB1 dataset. Please note that character “-” in tables indicated that the performance metric was not implemented by the authors in their respective papers. While it is possible to increase the segmentation accuracy of the proposed method by selecting preprocessing and filtering parameters for each dataset separately, the goal of the study is to propose a method that could be used on a variety of datasets and images. Although the proposed method is considered as an unsupervised segmentation, the results achieved are comparable to supervised segmentation methods while the processing time and computation requirements are notably lower, making the proposed method applicable for use in batch processing on large screenings. As mentioned, supervised segmentation methods require the computation of large pixel-wise feature vectors coupled with difficulties in training an efficient classifier, making them computationally demanding and time-consuming in batch applications.

Moreover, only some of the methods have outlined their preprocessing steps in detail [5, 7, 18, 19, 36, 39, 41, 61]. The results obtained on the DRIVE dataset showed that the proposed method was amongst the top methods with an AUC of 0.871, accuracy of 0.961, sensitivity of 0.761 and specificity of 0.981. In the case of the results obtained from the STARE dataset, with an AUC of 0.873, accuracy of 0.951, sensitivity of 0.782 and specificity of 0.965, the proposed method was also amongst the top methods proposed for retinal vessel segmentation with comparable performance to human segmentation. Although the CHASE_DB1 dataset has received less interest from researchers, the proposed method was able to achieve comparable results as compared to other methods with an AUC of 0.853, accuracy of 0.939, sensitivity of 0.738 and specificity of 0.968. As seen, the results are comparable to most recent supervised and unsupervised segmentation methods from the literature. It should be noted that the first observer has segmented thinner vessels in the CHASE_DB1 and DRIVE datasets as compared to the second observer, while the second observer has segmented thinner vessels in the STARE dataset as compared to the first observer resulting in a higher vessel segmentation sensitivity, as seen in Table 1.

The average processing times among various vessel segmentation methods are compared in Table 3. The proposed method required an average of 30 s to segment an image, making it comparable to most methods from the literature. Figures 10 and 11 show a visual comparison between the segmentation performance of the proposed method and other state-of-the-art methods for a sample image from the STARE and DRIVE datasets, respectively. As it can be seen, the proposed method was able to provide acceptable segmentation accuracy with low levels of artifacts and noise. Although the visual comparison is considered purely subjective, it can still emphasise the positive and negative points of various segmentation approaches in support of quantitative results. As seen, thin vessels and noise in the image represent major challenges in retinal vessel segmentation. Furthermore, images from STARE dataset are considered to have an inferior quality as compared to the DRIVE dataset, resulting in a lower performance.

A visual comparison between different retinal vessel segmentation methods on a sample image from the DRIVE dataset. a Color fundus image, b manual segmentation, c proposed segmentation, d method by Bankhead et al. [17], e method by Vlachos and Dermatas [71], f method by Martinez-Perez et al. [63], g method by Azzopardi et al. [19] and h method by BahadarKhan et al. [39]

A visual comparison between different retinal vessel segmentation methods on a sample image from the STARE dataset. a Color fundus image, b manual segmentation, c proposed segmentation, d method by Azzopardi et al. [19], e method by Vlachos and Dermatas [71], f method by Martinez-Perez et al. [63], g method by Bankhead et al. [17] and h method by BahadarKhan et al. [39]

Another advantage of the proposed method can be seen in pathological retinal images where non-vessel pixels can be easily identified as vessel pixels, degrading the usefulness of the segmentation. As illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13, the proposed method was able to provide less noisy segmentation as compared to other methods from the literature in pathological retinal images from the DRIVE and STARE datasets, respectively. Moreover, Fig. 14 compares the performance of the proposed method and the provided ground truth segmentation in some sample pathological images from the DRIVE and STARE datasets, respectively, while Fig. 15 illustrates the performance of the proposed method and the provided ground truth segmentation in some sample pathological images from the CHASE_DB1 dataset. The CHASE_DB1 dataset contains non-uniform background illumination with central vessels reflexes in most images and low contrast across the dataset where these issues result in lower segmentation accuracy, and consequently low interest to include this dataset in the development and testing of retinal segmentation methods.

A visual comparison between different retinal vessel segmentation methods on a pathological sample image from STARE dataset. a Color fundus image, b manual segmentation, c proposed segmentation, d method by Bankhead et al. [17], e method by Azzopardi et al. [19] and f method by BahadarKhan et al. [39]

4 Conclusions

Vessel segmentation can be considered as one of the main steps in retinal automated analysis tools. In advanced retinal image analysis, the segmented vasculature tree can be used to calculate the vessel diameter and tortuosity, discriminating veins and arteries along with measuring the arteriovenous ratio. Furthermore, segmented retinal vessels can be utilised as features for retinal disease classification and systematic disease identification systems, such as diabetes, stroke or hypertension. In this study, a retinal vessel segmentation algorithm based on fuzzy c-means clustering and level set method was proposed. Utilising morphological processes, the CLAHE and matched filtering techniques, the images were enhanced before the fuzzy clustering of vessel pixels. Finally, the vessels were segmented by a level set approach. The proposed segmentation method was validated on publicly accessible data sets by using common validation metrics in retinal vessel segmentation where the results on DRIVE (Sensitivity = 0.761, Specificity = 0.981), STARE (Sensitivity = 0.782, Specificity = 0.965) and CHASE_DB1 (Sensitivity = 0.738, Specificity = 0.968) were shown to be comparable to other methods from the literature. The proposed method was able to handle noisy and pathological images and produce good segmentation, especially in thinner vessels while being computationally efficient.

References

Asad, A. H., & Hassaanien, A.-E. (2016). Retinal blood vessels segmentation based on bio-inspired algorithm. In Applications of Intelligent Optimization in Biology and Medicine (pp. 181–215): Springer.

Solkar, S. D., & Das, L. (2017). Survey on retinal blood vessels segmentation techniques for detection of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes.

Niemeijer, M., Staal, J., van Ginneken, B., Loog, M., & Abramoff, M. D. (2004). Comparative study of retinal vessel segmentation methods on a new publicly available database. In SPIE medical imaging (Vol. 5370, pp. 648–656): SPIE.

Staal, J., Abràmoff, M. D., Niemeijer, M., Viergever, M. A., & Van Ginneken, B. (2004). Ridge-based vessel segmentation in color images of the retina. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 23(4), 501–509.

Soares, J. V., Leandro, J. J., Cesar, R. M., Jelinek, H. F., & Cree, M. J. (2006). Retinal vessel segmentation using the 2-D Gabor wavelet and supervised classification. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 25(9), 1214–1222.

Marín, D., Aquino, A., Gegúndez-Arias, M. E., & Bravo, J. M. (2011). A new supervised method for blood vessel segmentation in retinal images by using gray-level and moment invariants-based features. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 30(1), 146–158.

Fraz, M. M., Barman, S., Remagnino, P., Hoppe, A., Basit, A., Uyyanonvara, B., et al. (2012). An approach to localize the retinal blood vessels using bit planes and centerline detection. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 108(2), 600–616.

Ricci, E., & Perfetti, R. (2007). Retinal blood vessel segmentation using line operators and support vector classification. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 26(10), 1357–1365.

Li, H., Hsu, W., Lee, M. L., & Wong, T. Y. (2005). Automatic grading of retinal vessel caliber. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 52(7), 1352–1355.

Zhou, L., Rzeszotarski, M. S., Singerman, L. J., & Chokreff, J. M. (1994). The detection and quantification of retinopathy using digital angiograms. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 13(4), 619–626.

Yin, Y., Adel, M., & Bourennane, S. (2012). Retinal vessel segmentation using a probabilistic tracking method. Pattern Recognition, 45(4), 1235–1244.

Wink, O., Niessen, W. J., & Viergever, M. A. (2004). Multiscale vessel tracking. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 23(1), 130–133.

Yin, Y., Adel, M., & Bourennane, S. (2013). Automatic segmentation and measurement of vasculature in retinal fundus images using probabilistic formulation. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/260410.

Zhang, J., Li, H., Nie, Q., & Cheng, L. (2014). A retinal vessel boundary tracking method based on Bayesian theory and multi-scale line detection. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 38(6), 517–525.

Zhang, B., Zhang, L., Zhang, L., & Karray, F. (2010). Retinal vessel extraction by matched filter with first-order derivative of Gaussian. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 40(4), 438–445.

Gang, L., Chutatape, O., & Krishnan, S. M. (2002). Detection and measurement of retinal vessels in fundus images using amplitude modified second-order Gaussian filter. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 49(2), 168–172.

Bankhead, P., Scholfield, C. N., McGeown, J. G., & Curtis, T. M. (2012). Fast retinal vessel detection and measurement using wavelets and edge location refinement. PLoS ONE, 7(3), e32435.

Wang, Y., Ji, G., Lin, P., & Trucco, E. (2013). Retinal vessel segmentation using multiwavelet kernels and multiscale hierarchical decomposition. Pattern Recognition, 46(8), 2117–2133.

Azzopardi, G., Strisciuglio, N., Vento, M., & Petkov, N. (2015). Trainable COSFIRE filters for vessel delineation with application to retinal images. Medical Image Analysis, 19(1), 46–57.

Memari, N., Ramli, A. R., Saripan, M. I. B., Mashohor, S., & Moghbel, M. (2017). Supervised retinal vessel segmentation from color fundus images based on matched filtering and AdaBoost classifier. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0188939.

Fang, B., Hsu, W., & Lee, M. L. (2003). Reconstruction of vascular structures in retinal images. In Image Processing, ICIP. Proceedings. International Conference on (Vol. 2, pp. II–157): IEEE.

Al-Diri, B., Hunter, A., & Steel, D. (2009). An active contour model for segmenting and measuring retinal vessels. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 28(9), 1488–1497.

Läthén, G., Jonasson, J., & Borga, M. (2010). Blood vessel segmentation using multi-scale quadrature filtering. Pattern Recognition Letters, 31(8), 762–767.

Sun, K., Chen, Z., & Jiang, S. (2012). Local morphology fitting active contour for automatic vascular segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 59(2), 464–473.

Zhao, Y. Q., Wang, X. H., Wang, X. F., & Shih, F. Y. (2014). Retinal vessels segmentation based on level set and region growing. Pattern Recognition, 47(7), 2437–2446.

Yu, H., Barriga, E. S., Agurto, C., Echegaray, S., Pattichis, M. S., Bauman, W., et al. (2012). Fast localization and segmentation of optic disk in retinal images using directional matched filtering and level sets. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine, 16(4), 644–657.

Chaudhuri, S., Chatterjee, S., Katz, N., Nelson, M., & Goldbaum, M. (1989). Detection of blood vessels in retinal images using two-dimensional matched filters. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 8(3), 263–269.

Kovács, G., & Hajdu, A. (2016). A self-calibrating approach for the segmentation of retinal vessels by template matching and contour reconstruction. Medical Image Analysis, 29, 24–46.

Kande, G. B., Savithri, T. S., & Subbaiah, P. V. (2010). Automatic detection of microaneurysms and hemorrhages in digital fundus images. Journal of Digital Imaging, 23(4), 430–437.

Fraz, M. M., Basit, A., & Barman, S. (2013). Application of morphological bit planes in retinal blood vessel extraction. Journal of Digital Imaging, 26(2), 274–286.

Khan, K. B., Khaliq, A. A., & Shahid, M. (2017). A novel fast GLM approach for retinal vascular segmentation and denoising. Journal of information science and engineering, 33(6), 1611–1627.

Sigurðsson, E. M., Valero, S., Benediktsson, J. A., Chanussot, J., Talbot, H., & Stefánsson, E. (2014). Automatic retinal vessel extraction based on directional mathematical morphology and fuzzy classification. Pattern Recognition Letters, 47, 164–171.

Roychowdhury, S., Koozekanani, D. D., & Parhi, K. K. (2015). Iterative vessel segmentation of fundus images. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 62(7), 1738–1749.

Mapayi, T., Viriri, S., & Tapamo, J.-R. (2015). Comparative study of retinal vessel segmentation based on global thresholding techniques. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/895267.

Mapayi, T., Viriri, S., & Tapamo, J.-R. (2015). Adaptive thresholding technique for retinal vessel segmentation based on GLCM-energy information. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/597475.

Mendonca, A. M., & Campilho, A. (2006). Segmentation of retinal blood vessels by combining the detection of centerlines and morphological reconstruction. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 25(9), 1200–1213.

Hoover, A., Kouznetsova, V., & Goldbaum, M. (2000). Locating blood vessels in retinal images by piecewise threshold probing of a matched filter response. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 19(3), 203–210.

Owen, C. G., Rudnicka, A. R., Mullen, R., Barman, S. A., Monekosso, D., Whincup, P. H., et al. (2009). Measuring retinal vessel tortuosity in 10-year-old children: Validation of the Computer-Assisted Image Analysis of the Retina (CAIAR) program. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 50(5), 2004–2010.

BahadarKhan, K., Khaliq, A. A., & Shahid, M. (2016). A morphological hessian based approach for retinal blood vessels segmentation and denoising using region based Otsu thresholding. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158996.

Hong, X., Chen, S., & Harris, C. J. (2007). A kernel-based two-class classifier for imbalanced data sets. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 18(1), 28–41.

Zhao, Y., Liu, Y., Wu, X., Harding, S. P., & Zheng, Y. (2015). Retinal vessel segmentation: An efficient graph cut approach with retinex and local phase. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0122332.

Zhang, X., & Wandell, B. A. (1997). A spatial extension of CIELAB for digital color-image reproduction. Journal of the Society for Information Display, 5(1), 61–63.

Setiawan, A. W., Mengko, T. R., Santoso, O. S., & Suksmono, A. B. (2013). Color retinal image enhancement using CLAHE. In ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), International Conference on (pp. 1–3): IEEE.

Jones, J. P., & Palmer, L. A. (1987). An evaluation of the two-dimensional Gabor filter model of simple receptive fields in cat striate cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology, 58(6), 1233–1258.

Clausi, D. A., & Jernigan, M. E. (2000). Designing Gabor filters for optimal texture separability. Pattern Recognition, 33(11), 1835–1849.

Frangi, A. F., Niessen, W. J., Vincken, K. L., & Viergever, M. A. (1998). Multiscale vessel enhancement filtering. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (pp. 130–137): Springer.

Olabarriaga, S. D., Breeuwer, M., & Niessen, W. (2003). Evaluation of Hessian-based filters to enhance the axis of coronary arteries in CT images. In International Congress Series (Vol. 1256, pp. 1191–1196): Elsevier.

Zadeh, L. A. (1965). Fuzzy sets. Information and control, 8(3), 338–353.

Bezdek, J. C. (2013). Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithms. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Chen, S., & Zhang, D. (2004). Robust image segmentation using FCM with spatial constraints based on new kernel-induced distance measure. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics, 34(4), 1907–1916.

Krinidis, S., & Chatzis, V. (2010). A robust fuzzy local information C-means clustering algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 19(5), 1328–1337.

Ahmed, M. N., Yamany, S. M., Mohamed, N., Farag, A., & Moriarty, T. (2002). A modified fuzzy c-means algorithm for bias field estimation and segmentation of MRI data. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 21(3), 193–199.

Benaichouche, A., Oulhadj, H., & Siarry, P. (2013). Improved spatial fuzzy c-means clustering for image segmentation using PSO initialization, Mahalanobis distance and post-segmentation correction. Digital Signal Processing, 23(5), 1390–1400.

Niknam, T., Amiri, B., Olamaei, J., & Arefi, A. (2009). An efficient hybrid evolutionary optimization algorithm based on PSO and SA for clustering. Journal of Zhejiang University Science A, 10(4), 512–519.

Dréo, J., Petrowski, A., Siarry, P., & Taillard, E. (2006). Metaheuristics for hard optimization: methods and case studies. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Srinivas, M., & Patnaik, L. M. (1994). Genetic algorithms: a survey. Computer, 27(6), 17–26.

Maulik, U., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2000). Genetic algorithm-based clustering technique. Pattern Recognition, 33(9), 1455–1465.

Caselles, V., Kimmel, R., & Sapiro, G. (1997). Geodesic active contours. International Journal of Computer Vision, 22(1), 61–79.

Li, B. N., Chui, C. K., Chang, S., & Ong, S. H. (2011). Integrating spatial fuzzy clustering with level set methods for automated medical image segmentation. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 41(1), 1–10.

Lupascu, C. A., Tegolo, D., & Trucco, E. (2010). FABC: retinal vessel segmentation using AdaBoost. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine, 14(5), 1267–1274.

You, X., Peng, Q., Yuan, Y., Cheung, Y.-M., & Lei, J. (2011). Segmentation of retinal blood vessels using the radial projection and semi-supervised approach. Pattern Recognition, 44(10), 2314–2324.

Palomera-Pérez, M. A., Martinez-Perez, M. E., Benítez-Pérez, H., & Ortega-Arjona, J. L. (2010). Parallel multiscale feature extraction and region growing: application in retinal blood vessel detection. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine, 14(2), 500–506.

Martinez-Perez, M. E., Hughes, A. D., Thom, S. A., Bharath, A. A., & Parker, K. H. (2007). Segmentation of blood vessels from red-free and fluorescein retinal images. Medical Image Analysis, 11(1), 47–61.

Nguyen, U. T., Bhuiyan, A., Park, L. A., & Ramamohanarao, K. (2013). An effective retinal blood vessel segmentation method using multi-scale line detection. Pattern Recognition, 46(3), 703–715.

Orlando, J. I., & Blaschko, M. (2014). Learning fully-connected CRFs for blood vessel segmentation in retinal images. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (pp. 634–641): Springer.

Zhang, L., Li, Q., You, J., & Zhang, D. (2009). A modified matched filter with double-sided thresholding for screening proliferative diabetic retinopathy. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine, 13(4), 528–534.

Zana, F., & Klein, J.-C. (2001). Segmentation of vessel-like patterns using mathematical morphology and curvature evaluation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 10(7), 1010–1019.

Dai, P., Luo, H., Sheng, H., Zhao, Y., Li, L., Wu, J., et al. (2015). A new approach to segment both main and peripheral retinal vessels based on gray-voting and gaussian mixture model. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0127748.

Chanwimaluang, T., & Fan, G. (2003). An efficient blood vessel detection algorithm for retinal images using local entropy thresholding. In Circuits and Systems. ISCAS’03. Proceedings of the International Symposium on (Vol. 5, pp. V–V): IEEE.

Chakraborti, T., Jha, D. K., Chowdhury, A. S., & Jiang, X. (2015). A self-adaptive matched filter for retinal blood vessel detection. Machine Vision and Applications, 26(1), 55–68.

Vlachos, M., & Dermatas, E. (2010). Multi-scale retinal vessel segmentation using line tracking. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 34(3), 213–227.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. Chai Yee Ooi and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Memari, N., Ramli, A.R., Saripan, M.I.B. et al. Retinal Blood Vessel Segmentation by Using Matched Filtering and Fuzzy C-means Clustering with Integrated Level Set Method for Diabetic Retinopathy Assessment. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 39, 713–731 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-018-0454-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-018-0454-2