Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected several economic sectors in India, dragging many to the brink of survival. In particular, the already fragile horticulture industry is now facing a double burden of a weak value chain management system as well as perishability of produce (fresh fruits and vegetables), this pandemic season. Also, the strict enforcement of lockdown has altered both demand and supply factors, which in turn have shocked various linkages in the value chain of fresh fruits and vegetables. So, this paper dissects the value chain management of grapes and its processed products, namely juice, wine, and raisins in Maharashtra, the largest producer of grapes in India. For this, a value chain analysis (VCA) is carried out by computing the degree of value addition to uncover the rupture points caused by the pandemic as well as advocate policy measures to build a resilient system. The value chain analysis shows that post-COVID-19, the degree of value addition, has shot up for the intermediary agents, i.e., pre-harvest contractors, at the expense of the farmers. Using the insights from the VCA results plus the demand and supply shocks, various policy measures are elucidated to strengthen the grape value chain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has brought severe implications on the farming and food systems, mainly by affecting the agricultural value chains on several fronts. Among the value, chains that are facing a high level of losses include the fresh fruits and vegetable sector. The COVID-19 and its aftermath have heavily hit Indian fresh fruits and vegetable production and marketing. India acted swiftly to announce the lockdown in the middle of March, and the lockdown has been strictly enforced. While the lockdown has helped to keep the infections under control, it has disrupted the value chains of the high-value crops that are connected to regional and global markets. This disruption in the value chain could have serious ripple efforts on the agricultural economy. While internal value chains can be fixed over time, the interventional value chains and the post-harvest processing would be severely affected. Further, the loss in the international market could destroy the whole value chains, if necessary actions are not put in place to adjust to the new situation and build a more resilient and robust value chain (Meybeack and Redfern 2016). In this paper, we look at the grapes value chain in India, with particular emphasis on Maharashtra, the major producer, and processing state to understand the implications and guide the policy process of the state and national governments in the post-recovery period for building a more resilient value chain.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we provide an overview of the grapes value chains in the context of the horticulture sector in India. In section three, we present a conceptual framework to understand the factors that contribute negatively to the value chain management under the COVID-19 emergency. In section four, we present a case study of the grapes value chain in Maharashtra with a focus on responding to and learning lessons from COVID-19. Finally, concluding remarks are offered in the last section.

A conceptual framework for analyzing value chains under disease outbreaks and external shocks

In this section, we develop a simple framework for identifying the effects of shocks on the value chains of fresh fruits and vegetables. Horticulture is a vehicle to intensify land productivity and hence obtain more crops. Due to the fact that the market price of horticultural commodities is relatively higher compared with other crops, the income generated from the unite area of lands is also higher (Abou-Hadid 2005). So, studying the value chains and the distortions along the various linkages in the value chain is the first step to device appropriate interventions. Figure 1 presents the value chain mapping for fresh fruits and vegetables and the possible areas of disruptions denoted by a dot in the linkage arrows. The figure also includes the processing of fruits and vegetables, which are still emerging as a subsector in developing countries, particularly in India. An additional dotted arrow denotes this. As depicted in the figure, almost all linkages are affected by the COVID-19 emergency. The complete lockdown affects the use of labor in all stages of the value chain ranging from farming activities related to planting, inter-cultivation and harvesting, to the transportation of the produces in various stages of the value chain. The local markets are also affected in case there are restrictions to bring the produces to a common marketplace. The slowdown in the movement of the produces increases the wastages in the absence of adequate cold storage facilities for the perishable commodities (Jhajhria et al. 2020).

In Fig. 2, we identify the supply side and demand side factors that will affect the value chain management of fresh fruits and vegetables (Olhager et al. 2006). On the supply side, for example, issues related to labor supply for all farm operations, area planted and maintained, quantity harvested, reduction in the input supply, transport restrictions and the market restrictions affect production, marketing, and trade of fresh fruits and vegetables. On the demand side, the lockdown reduces the demand for fresh produce due to the restricted movement of the consumers and also because of the lower income earning capacity of the majority of the population during this pandemic period. Due to the closing of the institutions, the regular supply of fruits and vegetables to the mandis has drastically fallen. Collectively both the supply and demand factors contribute to the high-level disruptions of the activities along the value chain for fresh fruits and vegetables. We use this conceptual framework in developing the case study of the grape value chain in Maharashtra, India, to analyze the impact of COVID-19.

The case study of grape value chain under COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India

In this section, we present the case study of grape value chains in Maharashtra to illustrate the challenges as well as the opportunities that the COVID-19 emergency presents and the larger lessons to be learned. We present the case study in four parts. The first part delineates a brief description on the methodology and data collection procedures. In the next three parts, we present the results and discussion on the following: value chain analysis (VCA) of grapes in Maharashtra; disruptions in grapes value chains in the context of COVID-19 pandemic; and post-COVID-19 strategies for building a resilient value chain for grapes.

Data collection and methodology

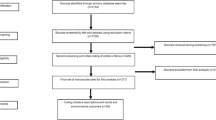

As Maharashtra is the leading state contributing around 76 and 78 percent of total grapes area and production, respectively, at all-India level, it was selected purposively for this study. This study is based on secondary data with additional information gathered through key informant interviews (KIIs) with select players on the grape value chains during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the officials of Directorate of Horticulture (DoH) through telephonic interactions. The relevant information about grape value chain operations was collected from independent grape growers and other significant players, including the degree of value addition across grapes value chains, possible disruptions in grape value chains, and strategies for building resilient grape value chain in the context of COVID-19 pandemic.

We generate the following measures for studying the grape value chain. Gross marketing margin (GMM) and net marketing margin (NMM) are derived as follows: GMMi is given by SPi − PPi, where GMMi is the GMM of ith player; SPi is the selling price of ith player; and PPi is the purchase price of ith player. NMMi = SPi − (PPi + MCi), where MCi is the marketing costs incurred by the ith player in the value chain (Hussain et al. 2013). Producer’s share in consumer’s rupee (PSCR) is given by (FNSP*100)/CPP, where FNSP is the farmer’s net selling price (after deducting the transaction costs of the farmer), and CPP is the consumer’s purchase price for the same quantity of produce handled. The degree of value addition by each market player is given by (NMMi/PPi)*100 (Imtiyaz and Soni 2013).

Results and discussion

VCA of grapes in Maharashtra

Grapes produced are widely consumed as fresh fruit. It is processed for producing a wide range of products, including raisins, wine, grape seed oil, jam, jelly, and juice concentrates. In India, 77% of grapes used as table grapes, 20% for raisin making, 2% for juice making, and 1% for wine preparation. There are 95 wineries in India, of which 77 are in Maharashtra, out of which 39 are in the Nashik district alone, the largest grape-producing district in India, making it the ‘Grape capital of India’ (ASSOCHAM 2013).

The total area and production of grapes in Maharashtra are 130 thousand hectares and 22.84 lakh tonnes, respectively, in 2018–2019. The year-wise data on area, production, and productivity of grapes in five dominant grape growing districts of Maharashtra for the period of last fourteen years, i.e., from 2003–2004 to 2018–2019, have been analyzed, and triennial averages are worked out (Table 1). The highest area under grapes was in Nashik district, which increased from 25.74 thousand hectares during TE 2005–2006 to 56.26 thousand hectares during TE 2018–2019 (Horticultural Statistics at a Glance, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India). Though the production of grapes has increased from 7.63 to 12.51 lakh tonnes, the productivity of grapes has declined from 29.65 to 22.23 tonnes/ha during the same reference period. Sangli district ranks second in the area and production of grapes, and it was 5.88 thousand hectares and 1.43 lakh tonnes, respectively, during TE 2005–2006.

During TE 2018–2019, both the area and production of grapes showed increasing trend and reached to 21.89 thousand hectares and 5.82 lakh tonnes, respectively. Similarly, the productivity of grapes also showed a rising trend from 24.31 to 26.61 tonnes/ha during the same reference period. Solapur, Pune, and Osmanabad stand third, fourth, and fifth positions in the area under grapes, respectively. The area and production of grapes showed an increasing trend across all these three districts during TE 2005–2006 to TE 2018–2019, while the productivity of grapes increased in Solapur and decreased in Pune and Osmanabad districts during the reference period. Due to the extended monsoon, there were heavy rains when grapes are at the fruit formation stage, and the crop in the major grape producing districts, viz. Nashik, Sangli, Solapur, and Osmanabad districts suffered severe damage in 2016–2017 and 2017–2018. Further, unseasonal hailstorm and rainfall across these four districts during 2018–2019 adversely influenced the grapes productivity in these districts. However, the farmers in Pune witnessed higher productivity during the above reference periods, as they have taken early harvest of the fruit for selling to some northern states as well as for exporting it to Bangladesh. So, the grapes from Pune reached market in the month of November, whereas from other districts, the peak arrivals started only from January. This led to higher productivity of grapes in Pune, unlike other districts. Thus, in terms of area, production, and productivity of grapes during TE 2018–2019, Nashik and Sangli are two predominant districts in Maharashtra. Next to these five major grape growing districts, grapes are grown in Ahmednagar, Satara, Latur, and Jalana districts on nearby 500 hectares acreages in each district during TE 2018–2019.

Mapping value chain of grapes

The value chain of grape is complex, with many interconnected players operating in more than one value chain. In Nashik, some of the stakeholders are nursery developers, input suppliers, farmers, pre-harvest contractors (PHC), traders, wholesalers, processors cum wholesalers, retailers, and service providers. Key institutional players include, National Research Centre for Grapes (NRCG) of Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), DoH, Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs), Maharashtra State Agricultural Marketing Board (MSAMB), Mahagrapes (co-operative partnership established with the help of the MSAMB), Maharashtra State Grape Growers Association (MSGGA), National Horticulture Board (NHB), and Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA).

Based on the functions performed by various actors in the value chain of grapes, Fig. 3 depicts the entire process right from the flow of resources and services to the farmers and up to the final delivery of product to the customer.Footnote 1 The key stages in the value chain are given in the rectangles, below which respective actors associated with these functions are indicated. Corresponding institutional support activities by KVKs, DoH, MSGGA, NRCG, Good Agricultural Practices (GAP), Good Marketing Practices (GMP) are given above each stage. Hexagonal boxes represent the movement of the produce in the local, upcountry, and export markets. Actors involved in these markets to transact both fresh grapes and processed produce are indicated through arrows of the respective colors.

Degree of value addition in transacting grapes and its products After mapping the value chain of grapes, we calculate the degree of value addition on fresh and processed grapes (raisins) (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5). From Fig. 3, the following value chains are identified for transacting grapes in Nashik, Maharashtra.

S. no | Commodity /product | Predominant value chains | % of Marketable surplus transacted |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Fresh Grapes | Farmer → PHC → Wholesaler in Fruits and Vegetables market → Retailer → Consumer | 55 |

Farmer → PHC → Local Exporter → Retailer → Consumer | 12 | ||

Farmer → Wholesaler in Fruits & Vegetables market → Retailer → Consumer | 21 | ||

Farmer → Retailer → Consumer | 7 | ||

Farmer → Consumer | 5 | ||

2 | Grape juice | Farmer → PHC → Processor cum Wholesale Distributor → Retailer → Consumer | 55 |

3 | Raisins | Farmer → PHC → Processor cum Wholesale Distributor → Retailer → Consumer | 60 |

4 | Grape wine | Farmer → PHC → Processor cum Wholesale Distributor → Retailer → Consumer | 45 |

During the pre-COVID scenario, the degree of value addition for table grapes (Thomson seedless) indicated that 23% of the value addition takes place during the sale of the produce from PHC/trader to wholesaler followed by 28% during the sale of produce to the retailer (Table 2 and Fig. 4). At the retailer level, 21% of value addition takes place during the sale of produce to the ultimate consumer. Compared to retailer, the extent of value addition by the wholesaler is a little bit higher, as he has to perform facilitating functions like cleaning, grading, weighing, storage, packaging, and packing. However, in case of table grapes, there is little variation in the degree of value addition at different stages from the growers to the end consumers because there will not be any change in the form of grapes. It is interesting that in this value chain, the transaction costs are increased for PHC, while the same was decreased for wholesalers and retailers during post-COVID scenario compared to pre-COVID scenario. This is because with the advent of corona pandemic, the farmers started early harvesting of grapes, fearing about shortage of labor in the near future. The PHC exploited this (glut) situation, and they even went to remote villages to procure the produce at low prices. Though they incurred more transaction costs, they realized higher NMMs due to lower purchase price of fresh grapes from the farmers. They further moved the produce to local assembling centers; thus, the wholesalers and retailers incurred lower transaction costs compared to PHCs.

However, in the value chain of grape juice, 27% of value addition takes place during the sale of the produce from PHC to processor cum wholesaler followed by 47% of value addition during the sale of juice from the latter to retailer (Table 3). Only 5% of value addition takes place during the sale of juice from the retailer to the ultimate consumer. This implies the processing function from raw grapes to grape juice ensured more value addition in the transaction process. The farmers cultivating grape varieties suitable for grape juice (and raisins also) enjoy contractual agreement with the local processors cum wholesalers in the district. Due to lack of adequate cold storage facilities in the district and with the grape juice processors (existing storage capacity already in full), the processors could not advocate the farmers to go for early harvesting of the produce. Consequently, the transaction costs incurred by the juice processors cum wholesalers and retailers was increased during post-COVID scenario because of acute labor shortage and transportation bottlenecks.

Similar is the case in the value chains of raisins and grape wine, as the extent of value addition is greatest during the processing function, i.e., 66 and 83 percent, respectively (Tables 4 and 5). That is, at processor level across the above three value chains, the extent of value addition for the final product is significantly higher, as, in this stage, the grapes are converted to a more value-added product. As in the case of grape juice, even for both these products (i.e., raisins and grape wine), the extent of value addition at the retailer level is very meager (4 and 3 percents, respectively). Even during the post-COVID scenario, the demand for processed products of grapes (grape juice, raisins, and grape wine) is on the rise, as their consumption promotes immune to the customers. This prompted the PHCs to procure the produce even from the remote villages at lower prices though incurring higher transaction costs and later they supplied the same to local wine processors and able to realize higher NMMs. On the contrary, the wine manufacturers operating on large scale enjoy tie up or contractual agreements with the farmers have recommended the latter to harvest the produce well in advance to overcome labor shortage. These manufacturers have their own transportation networks, and thus, they incurred lower transaction costs, unlike PHC and retailers.

Across all the four value chains, at the retailer’s level, the degree of value addition is less as compared to the previous stage because the retailer do not perform any value addition activities. This analysis also highlights that by processing the grapes, the agency, i.e., processor cum wholesaler is gaining maximum NMM to the tune of 17, 19, and 25 percent in the respective consumer’s purchase price (CPP) in transacting grape juice, raisins, and grape wine, respectively. However, the farmer’s share in the CPP is highest when transacting fresh grapes (Table 2) to the tune of 34%, and this share declines in the production of processed products.

During the post-COVID scenario, it is quite disheartening to note that the PHCs gained significantly in procuring fresh grapes in the value chains at the cost of farmers. As there is declined demand for fresh grapes in the market due to barriers in inter-state transport (consequently domestic supply exceeds the local demand) and processors have to necessarily utilize the installed capacity of processing equipment/machinery and increasing demand for processed products like raisins and grape juice (improve the immune system of consumers), the PHCs have greatly benefited in the value chain of grapes. So, the PHCs exploited the situation by quoting a low price to the grape growers, arranged their own labor (even engaged students of local schools/colleges) to harvest and transport the grapes. So, the PHCs with their strong backward and forward linkages in the value chains, i.e., with farmers and processor cum wholesalers respectively, are actively involved in procuring the fresh produce from the farmers’ fields directly and transacting the same at exorbitant prices to the subsequent agencies. As a result, the degree of value addition of PHCs in the value chains of grapes and its processed products showed a considerable increase during the post-COVID period compared to the pre-COVID scenario. Accordingly, the increase in the degree of value addition of PHCs in transacting fresh grapes to wholesalers (for table purpose) is highest to the tune of 38% (Table 2 and Fig. 4). This is followed by grape juice (32%), raisins (20%), and grape wine (15%) during the above reference period in transacting fresh grapes from PHCs to respective processors. Even the degree of value addition by processor cum wholesalers of grape juice and raisins showed increasing trend by 12 and 11 percent, respectively, during the above reference period.

So, with the drastic increase in NMMs of both PHCs and wholesalers (table grapes)/processor cum wholesalers (grape juice, raisins, and wine), the PSCR declined during the post-COVID period compared to the pre-COVID scenario. These findings highlight poor market linkages of farmers in transacting grapes in the local market. The disruptions in the grape value chains in terms of labor shortage, transportation, cold storage, and other logistics further aggravated the problems at the farmer's level. The intermediary agents closest to the grape growers in the locality, i.e., PHCs, gained significantly during this post-COVID period. They exploited the farmers by quoting a low price for the produce, arranging for labor to harvest the produce, transport of produce from farm gates to cold storage units and processing units. Their linkages with the cold storage units in the locality further exploited the farmers, as the latter could not avail such facility. All these factors cumulatively affected the farmers in deriving low price for their produce and hence low PSCR in transacting grapes across value chains of both fresh and processed products.

The discussions held with the officials of DoH revealed that since the local mandis are now closed, there is no other go for the grape growers to transact their produce directly to the PHCs. Some growers are even entering into verbal agreements with the PHCs in the post-COVID period to support their orchards in the future. Though MSGGA has taken the lead earlier to bring Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) associated with grape farming under a common federation, the marketing of grapes from this federation too got affected during the post-COVID period. It was observed that a farmer under this federation would have earned Rs. 250 per box in the international market, but instead, now has to settle for the price of Rs. 70 per box in the local market. Grapes from FPCs under a common federation are commonly exported to West Asia and European countries, but it has halted due to this pandemic. It was estimated that due to this pandemic, the grape industry suffered a huge loss of around Rs. 1000 crore, as the harvesting has paused, and now the produce is found rotting in the fields. Even if inter-state transport revives due to exemptions given by the government during lockdowns, still the demand may not shoot up for fresh produce because the big buyers are far away, and urban demand is likely to be minimal during the lockdown period. When the grape market collapses, farmers turn to raisins. It ensures return of at least the production cost with 100 kg of grapes turned into 25 kg of raisins. But farmers are facing trouble on this front as well, as they need dipping oil and potassium carbonate to make raisins. These two products are usually imported from China. Typically, the cost of dipping oil stands at Rs. 190 per liter, and potassium carbonate costs about Rs. 100 per kg. But with no import, the farmers are forced to buy both the products at inflated prices of Rs. 230 and Rs. 120, respectively. One liter of the oil and one kg of carbonate is required for the making of 100 kg raisins. At a time when farmers are already incurring losses, the increased cost of the two items is digging a deeper hole in their pockets.

Disruptions in grapes value chains in the context of Covid-19 pandemic

COVID-19 is officially a global pandemic, now confirmed in 227 countries and responsible for 2.83 lakh plus deaths (as on May 10, 2020), and this has affected all the sectors in general and especially the high value crops sector in particular. Though India has taken early action through ordering nation-wide lockdown for its population of 1.3 billion people since March 20, 2020, the novel coronavirus disease was spreading fast when compared to other countries. These measures will hit the horticulture sector in Maharashtra and the possible implications of the COVID-19 pandemic situation—now and in the future (Fig. 5)—for grapes production, value chain mechanism, and export markets are presented hereunder.

Declined production and domestic demand for grapes As this pandemic disease is spreading quickly and is no longer a regional issue, there are restrictions on the sale of inputs, (fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, etc.), availability of labor, quarantine issues, etc., and these could affect the production adversely. The harvesting season (January to April) of Thompson seedless—one of the predominant varieties cultivated in Nashik, coincided with the lockdown period. Hence, the harvesting of grapes was affected, leading to rotting of fruits in the fields. The domestic demand for grapes (and other fresh fruit and vegetables) will probably decrease because of deterioration of consumer mood, worse income situation of many households, temporary closing of schools and colleges, reduction of sales at local mandis, limited activities in the food service due to the closure of shopping malls, movie theatres, restaurants, marriage halls, temple festivals, households (reduced purchasing power), and others.

Logistics bottlenecks Up to the end of March 2020, the value chain disruptions are minimal, as grapes supply has been adequate, and markets have been stable. However, since April 2020, the challenges due to logistics bottlenecks and labor shortage are on the rise, and this greatly affected the flow of produce in the value chain. Due to grapes' delicateness and extreme perishability, the losses due to limited transportation logistics are severely high. Closure of local mandis and blockages of inter-state transport routes are particularly obstructive for fresh grapes supply chains and also resulted in increased levels of produce loss and waste. Harvested grapes are rotting as there are no trucks available to transport the fruit to neighboring states like Telangana, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Mumbai, Gujarat, Delhi, and Tamil Nadu. Though FPCs have been allowed to sell fresh grapes in local markets, they cannot absorb the excess production.

Panic buying of processed products Interestingly, the recent outbreak of the coronavirus has greatly affected people’s behavior. On the demand side, people are stockpiling shelf-stable food, like processed fruits and vegetables. On the supply side, the processing companies are struggling to meet this demand due to labor and logistics capacity issues. This panic buying of customers has positively affected the demand for processed fruit juices and products. This is so because, with the outbreak of the corona pandemic, it has become all the more important to have a strong immune system. The new researchFootnote 2 suggests that besides orange juice, grape juice may be an immune system booster, too and the people who sipped Concord grape juice daily for nine weeks had higher blood levels of a special type of infection-fighting cell. However, the people prefer to have small can sizes (say up to 5 kg) of processed fruit juices (say, grape juice), and with the closure of restaurants, the demand for bigger cans has drastically decreased. This forced the juice and wine processing units in Maharashtra to cancel their prior orders for fresh grapes from the farmers. So, the farmers have had many order cancellations, forcing them to redirect produce to sell as table grapes. On the negative note, panic buying and hoarding in some parts of Maharashtra added to worries that wholesalers and retailers, whose inventories are small, are wiped out of the business.

Price crash Since mandi operations have almost stopped, the grape farmers are in a panic because ripened grapes will rot. Further, farm gate prices are plunging, as many PHCs have halved the price they pay farmers, while remote farmers are not even finding buyers.Footnote 3 Considering the severity of the spread of the pandemic in Maharashtra, the state is not allowing the farmers to harvest, go to market yards, and prevent buyers from buying, though the center is emphasizing on allowing the essential services. Farmgate prices of fresh grapes have fallen by 15–20 percent in the open market, as bulk demand from hotels and restaurants has nosedived, and there is uncertainty over exports. The introduction of temporary border controls may additionally cause some difficulties to increase market supply beyond local demand and this leads to price crash.

Declined exports Around 35,000 tonnes of fresh grapes of Maharashtra to be exported into the international market got affected, as the customs gates of Netherlands, Russia, the UK, and China were closed due to the coronavirus epidemic. In December 2019, China first suspended customs clearance of goods at its border gates to prevent the spread of the disease, resulting in congestion of goods in India–China border gates. So, the export of fresh grapes from Maharashtra to China is greatly affected. All these resulted in a glut, and consequently, there is a severe price crash of grapes (and other fresh fruits) in the domestic market. Though farm-gate prices of fresh grapes have fallen due to COVID-19 scare, the demand for processed products has not been affected both in domestic and international markets. This is because, as of now, there is no dearth of stock of produce (processed grape products) lying in the supply chain, as most of the exporters and traders across the country generally keep a buffer stock of 45–60 days. So, presently, the supply chain is fully geared up and be able to deliver goods, and hence, packaging and dispatches for exports of processed products have not decreased.

Adverse impact on Cargo business In Maharashtra, the cargo business got negatively impacted, as the cargo vessels that primarily arrive in Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT), Mumbai from China, Thailand, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Italy, and Iran (these countries are also battling against the COVID-19) are closed (since April 1, 2020) by the port officials for taking all necessary precautions to prevent the spread of coronavirus. Likewise, the export of processed grape products (raisins, grape juice, and grape wine) was drastically declined to the Netherlands, Russia, the UK, Germany, UAE, Saudi Arabia, China, etc., due to the closure of JNPT. Due to the multitude of possible scenarios, it is difficult to clearly assess the possible scale of coronavirus impact on the fruit and vegetables sector in Maharashtra.

Severe financial distress The current lockdown in the country due to the coronavirus pandemic has hit grape growers in Maharashtra hard. With no buyers in sight, instead of letting the grapes rot, growers of seedless grapes are now looking at the option of drying and converting them into raisins, which has huge market demand. So, the ICAR-NRC-Grapes, Pune, has advised grape farmers to convert ‘table grapes’ to ‘raisins’ by drying the berries on the vine. However, the cost of chemicals, which include dipping oil and potassium carbonate, has gone up and is in short supply (discussed earlier). The DoH estimated that nearly 40,000 ha of grape cultivation in Nashik, Sangli, and Solapur had been affected due to the outbreak. On the remaining 60,000 ha, farmers are looking at processing the grapes from 30,000 ha to raisins. These are in addition to the regular raisin processors. Lack of export and declining demand in the domestic market have posed a double whammy for grape growers. Also, storage issues are on the rise, as all the cold storages for grapes are full and have another 300–400 containers and exporters have stopped packaging of these grapes. So, grape growers from the state are seeking a loan waiver and grants to overcome financial distress.

Effects on market players in grape value chains The major market players of the grape value chain in Maharashtra, viz. PHC, wholesalers, and processors, are being watchful during this pandemic and trying their best to minimize the adverse effects on them and hence, on the public. Now, in the ensuing two to three months say, up to June 2020 the two agencies, viz. PHC and wholesalers, continue their business operations and focused on the sale of fresh produce directly to processors, as processed products (raisins, grape juice, and wine) have higher market demand in the context of promoting immune to the consumers against coronavirus. However, the retail business of fresh grapes has taken a hit, as the state government shuttered non-essential businesses, including restaurants, and set strict limits on numbers of people allowed to gather. Retail grocery stores, however, remained open, and that is the heart of the fresh and processed grapes market.

Post Covid-19 strategies for building a resilient value chain for grapes

Based on the developments from this pandemic, coupled with learnings from past disruptive instances, below are some key pillars to help market players build a resilient value chain for grapes in India and with special reference to Maharashtra (Fig. 6).

Re-assessment in supply chain strategies There should be a thorough re-assessment of present supply chain strategies. Each market player in the grape value chain should re-assess their ‘disaster plan’ armed with the knowledge from this crisis of just how much degree of their value addition got affected. It is essential to immediately structure and apply the lessons learned to build a resilient supply chain for the future. This corona pandemic helped the market players in getting awareness about the inherent risks in the existing value chains and thus helps to formulate suitable recommendations to design a newly structured and more reliable value chain setup.

Redefining the Roles of Government agencies To rebuild a robust value chain for grapes, it is high time that the government enhances the role of the corporate sector toward public–private partnership (PPP) projects to enhance markets and players connectivity as well as strengthen global value chains with viability-gap funding to make those investments profitable. Special trains with refrigerated coaches should be provided to promote transportation logistics, especially for fresh fruits like grapes.

Digital horticulture Digital technology, like artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, blockchain technology, Internet of things, etc., can play a transformational role in modernizing horticultural activities and helps to disseminate valuable information regarding grape farming, crop-related advisories through SMS and online portal, launching an online trading platform, provision of subsidies, etc. Better connectivity through digital means can unlock wider opportunities for the PPP and government’s interventions as well as stakeholder’s participations both in production and trading aspects of the fruit crops.Footnote 4 In a bid to mitigate the challenges faced by stakeholders, especially farmers, on April 2, 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture and Famers’ Welfare has introduced warehouse-based trading module and Farmer Producers’ Organizations (FPOs)-based trading module to transact the produce directly from registered warehouses and collection centers, respectively, through e-NAM to avoid overcrowding in APMC markets.

Collective action by the Government and cooperative organizations Keeping the pandemic in mind, the DoH, MSAMB and National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD-encourage FPOs) and MSGGA (encouraging grape growers cooperatives) jointly initiated steps to tackle this problem through a convergence of their respective roles and responsibilities. They all approached growers cooperatives and FPOs to develop their own mobile apps for online marketing of fresh grapes. To support these transactions in the state, the Public Transport Department has developed a system for issuing a vehicle e-Pass through the link: covid19.mhpolice.in. In addition to this, MSAMB set up the ‘Inter-State Fruits and Vegetables Control Room’ with a toll-free number—1800-233-0244—to manage smooth movement and dispute settlement, if any. This collection action has yielded fruitful results through transacting 222 M. Tonnes of fruits and vegetables have been sold from March 27 to April 15, 2020. Amidst the lockdown, the FPOs are exploring alternative marketing channels to connect directly with consumers. For instance, Sahyadri Farms of Nashik, a leading FPO with 1200 farmers, reportedly sold vegetables and fruits worth over Rs. 4 crores during the lockdown by establishing a direct link with 57,000 customers.

Agri-Tech start-ups In the backdrop of the lockdown one such start-up—AgSource: Global Agri Trade Pvt. Ltd., a joint initiative of AgSource Group’ and Vegetable Growers Association of India (VGAI)—began working as farmers marketing, and customers procurement arms’ to provide the best quality veggies and fresh fruits to customers at their doorsteps. Daily 200 fruits and vegetables baskets (standard package for a week of 10–15 kg each, and customized package as well) are being delivered to housing societies in Pune and Mumbai as per the orders received from the customers. This WhatsApp group is not only meeting the needs of people but also creating awareness by sharing precautionary messages and images. There is a Win–win situation by Integrating FPOs and Agri-Tech Start-ups. On one side, FPOs are demanding appropriate and advanced technology for improving the efficiency of their business operations besides technology for improving farm productivity. On the other hand, many agri-tech start-ups are ready with their prototypes but find no end users.

Capacity building of grape growers cooperatives and FPOs In Maharashtra, both the Grape Growers Cooperatives and FPOs need to be trained on the Governance, Financial Management, Business Development Plan, and Leadership aspects to run and manage their businesses effectively and efficiently and thereby make them competitive and sustainable. The Vaikunth Mehta National Institute of Cooperative Management (VAMNICOM), an apex training institute for producers’ collectives, National Institute of Agricultural Marketing (NIAM), and National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE) shall undertake such training for cooperatives and FPOs.

Investments in sustainable infrastructure Due to the financial crisis amidst the corona pandemic, India should take the opportunity to increase support toward green measures such as renewable energy, particularly rooftop solar, through appropriate policies, and business models. Similarly, continued investments in cold storage facilities and supply chains will ensure the preservation and timely delivery of agricultural produce and reduce losses to market players. Further, the government should explore approaches for building a low carbon, green, and resilient value chains. Environmental protection and provision of ecological services should be viewed as key components of economic growth rather than viewing environmental protection as a competitor for achieving economic growth.

Make the supply chain visible through digitization To ensure visibility across the entire supply chain, the trade should move away from paper to digitization. Digitizing the transactions and records ensures visibility and managing value chain risk. To address the points of disruptions in the value chains, it is important to make data available through digital means. Technologies accompanied by enabling policies can play a significant role in rebuilding the value chain system and making the value chain more shock proof in the decades to come.

Reliance upon global supply chains In the context of the corona pandemic, it is important to rely upon global supply chains, as they will reduce, particularly on single sourcing of components, raw materials, and finished products. In the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, the Government of India has identified 21 agricultural products, including honey, potatoes, grapes, soya beans, and groundnuts, in which Indian exports could benefit from trade restrictions against Chinese goods. The total value of China’s global exports of these products amounted to $5488.6 million in 2018. India exported $4445.9 million worth of these commodities in the same period and could now have a chance to grab part of China’s market share. So, there may be opportunities for Indian exporters of agri-items, in case some countries impose restrictions on Chinese goods in response to the outbreak of COVID-19.

Changing consumer expectations During this pandemic, there is a significant increase in home delivery and Click and Collect of products in all the sectors. This new shopping trend will lead to the evolution of modern value chains for several products and even for fresh agricultural produce like grapes, mangoes, apples, pomegranate, etc. This scenario also affects the business firms in two ways, viz. increasing business capacity in tune with the customers’ needs and serving the products online either for free or at a low cost, and that may be a sustainable business model only in the long run. This will ensure both value chain resilience and value chain efficiency.

Redirect farm supply chains to local areas Since towns and cities have reduced operations at this point due to corona pandemic, the harvested grapes are going waste, and costs are not breaking even. So, the existing supply chains can be re-directed to local areas by incentivizing farmers to sell more and more of their produce in local cooperative style channels. Mobile vans should be allowed to sell off the stock and supplies. This will allow for retail distribution to be more seamlessly linked with largely wholesale supply-lines.

Physical safety of supply-chain workers In the post-COVID scenario, introducing new marketing reforms to ensure supply chain resilience can be considered similar to opening Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in manufacturing sector. This is essential at least now, as the agriculture sector in India is not liberated to the extent compared to the industry. So, without compromising food security, agricultural marketing is to be liberated and focus should be on accessing toward global supply chains. Above these, the market players in the supply chains should consider the health and well-being of supply chain workers, supporting their mental health and emotional and physical needs as well as their physical safety. It is extremely vital that they should be provided with adequate amount of safety kits and protective gear to be able to ensure safe, orderly distribution of supplies at less risk of virus transmission.

Concluding remarks

COVID-19 emergency and the responses toward containing the disease have enormous implications for the agriculture sector as well as the food and agriculture value chains. Measures to mitigate the negative effects of disease outbreaks and similar shocks to the agriculture sector require analyzing the factors disrupting the value chain at various stages and removing these obstacles through programs and policies. In this paper, we have looked at the grapes value chain in Maharashtra, India, to identify possible lessons for improving the resilience of the value chain operations.

As agriculture accounts for 16.5 percent of India’s GDP and nearly half the population in the country depends on a farm-based income, the big focus should be on new ideas to intervene in the agriculture marketing system to ensure livelihood security of both farming population and agricultural laborers. It is high time to promote integrated markets, i.e., one state should be agreeable with another state, to have a free flow of products and ensure transparency in the supply chain (www.outlookindia.com). So, the government should consider for ‘removal of levies’ charged from traders when farm goods are sold from one state to another, known as inter-state mandi tax. The focus should be on making strategic interventions in the existing marketing ecosystem and bringing appropriate reforms in the context of rapid agricultural development. There should be massive scaling up of a federal e-commerce platform for farmers and traders, i.e., selling through e-NAM app.

As the pandemic will not be over soon, it is essential to look for the points of disruptions in the supply chains and act accordingly. Also, ascertain their root causes and how they can be strengthened. The government should plan for reallocation of resources to support the market players across the whole value chain and to enhance overall resilience and help any areas of the supply base at risk from operational and/or financial disruption. Government and market players of the value chain should take equal responsibility to keep planning for the investments needed once this crisis passes and economies rebound while building in the purposeful and responsible features developed during the pandemic (Vita et al. 2020). Finally, it is essential to ensure the smooth and seamless functioning of the market players for continuity in the value chain of grapes and imparting resilience in the ecosystem, even during the post-COVID-19 pandemic and related situations.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data and material will be available on request.

Code Availability

The code will be available on request.

Notes

Kavita Swain, A study on Value chain analysis of mango at Dhenkanal district, Unpublished MBA thesis submitted to Department of Agribusiness Management, Center for Post Graduate Studies, Orissa University of Agriculture & Technology, Bhubaneswar, 2017.

The Hindu Business Line—Covid-19 puts India’s food supply chain to a stress-test.

The Economic Times—Coronavirus_ COVID-19_ EU relaxes fruit & veggies imports; no orders from US—May 27, 2020.

References

Abou-Hadid DA (2005) High value products for smallholder markets in West Asia and North Africa—trends, opportunities and research priorities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy

ASSOCHAM (2013) Horticulture sector in India-state level experience. The Associated Chamber of Commerce and Industry of India, New Delhi

Horticultural Statistics at a Glance—Various Issues. (n.d.). Horticulture Statistics Division, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare, Government of India

Hussain MB, Aslam M, Rasool S (2013) An estimation of marketing margins in the supply chain of tobacco in District Faisalabad Pakistan. Acad Res Int 4(6):402

Indian Horticulture Database (2013–2014) Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India

Imtiyaz H, Soni P (2013) Evaluation of marketing supply chain performance of fresh vegetables in Allahabad district, India, Int J Manag Sci Bus Res, vol 3(1), ISSN (2226–8235)

Jhajhria A, Kandpal A, Balaji SJ, Jumrani J, Kingsly I, Kiran Kumar, Nikam V (2020) Covid-19 Lockdown and Indian Agriculture: options to reduce the impact. Delhi: ICAR-National Institute of Agricultural Economics and Policy Research

Meybeack A, Redfern S (2016) Sustainable value chains for sustainable food systems. In: Workshop of the FAO/UNEP on sustainable food systems. food and agriculture organization of the United Nations

Olhager J, Selldin E, Wikner J (2006) Decoupling the value chain. Int J Value Chain Manag 1:19

Vita MA, Walko J, Banerjee S, Held M, Rose K (2020) Repurpose your Supply Chain. Accenture

Acknowledgements

The funding support from CGIAR Research Program on Policy, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) is greatly acknowledged toward the completion of the manuscript. Authors would also like to thank Sri Dattaji Rao Suryavamshi and Sri Sita Ram Dhumal, National Facilitators for Maharashtra and Mahesh Mane, Consultant for Maharashtra from MANAGE for collecting requisite data and information.

Funding

CGIAR Research Program on Policy, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) has partially funded for Dr. Suresh Babu’s work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ravi Kumar, K.N., Babu, S.C. Value chain management under COVID-19: responses and lessons from grape production in India. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 23 (Suppl 3), 468–490 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00138-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00138-6