Abstract

Purpose

According to the Developmental Ecological Action Model (DEA) of the situational action theory (SAT), changes in crime rates over the life-course are explained through personal (moral) maturation and socio-ecological selection. This assumption is empirically tested by comparing results for the conditioning effect of the principle of moral correspondence (as an essential part of SAT’s perception-choice process) on crime rates for the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Methods

Comparing two waves of a German longitudinal study (CrimoC, 17 and 26 years old, n = 1738), a series of logistic and multinomial logistic regressions and ensuing estimated transition probabilities capture the cross-sectional but also developmental processes involved. Additionally, the CrimoC study offers a differential analysis of offending scales, separating offenses into youth and adult crimes.

Results

The principle’s conditioning effect on crime could be replicated at both times. We can observe a general trend of individual transitions, which correspond to predicted personal maturation and socio-ecological selection. The transitions correlate with the expected reduction in crime rates over time. Males and females show comparable results. The separation into different offending scales yielded tentative insights.

Conclusion

We found stability in the mechanisms leading to crime as proffered by SAT and DEA across time. Personal (moral) maturation and socio-ecological selection are likely to be the driving forces behind reducing crime in adulthood. Future research needs to explain in detail how life-course events influence these factors. Considering adult crimes in the analysis is a promising endeavor that warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The positive relationship between someone’s delinquency and peers’ delinquency is a classic finding in criminology (Warr 2002; Haynie and Wayne Osgood 2005; Matsueda and Anderson 1998; Warr and Stafford 1991). Also well-documented in the literature is the effect of moral values on offending (Antonaccio and Tittle 2008; Piquero et al. 2016; Schoepfer and Piquero 2006; Vazsonyi et al. 2001). Warr (2002) bridges these two phenomena by dissecting the different possible angles through which peers influence delinquency. Among these is the peer group as a moral universe (Warr 2002). He claims that in longer-lasting social interactions, such as marriage, partnership, and also friendship, “the moral ‘I’ is subsumed into the moral ‘we,’ and emerging rules of conduct become ‘our’ rules” (Warr 2002: 65). These rules can even supersede generally accepted norms not to commit offenses. An “individual may know perfectly well what his parents, teachers, and preacher say is right and wrong, and yet violate this without feelings of guilt if his fellows do not condemn him” (Sherif and Sherif 1964: 182).

The peers’ moral support after an illegal act is committed functions mainly due to the diffusion of moral pressure that individuals would receive from parents or other guardians after committing a crime. Warr defines three mechanisms by which this is achieved: “they [i.e., individuals] deflect (anonymity), dilute (diffusion of responsibility), or supplant (with an alternative code) the moral responsibility for illegal behavior” (Warr 2002: 70) through association with their peers. These neutralizing strategies through peers and their perceived moral codes are potent elements that can encourage illegal behavior. We will argue with Wikström’s situational action theory (SAT; Wikström et al. 2012) that peers provide a moral context in settings and, therefore, constitute whether offending is considered a viable action alternative in a given situation.

However, analyzing the National Youth Survey, Warr (2002) also informs on the rather steep decrease in the importance of peer relations after its peak at age 17. Therefore, the peers’ role in individuals’ lives follows a transitory development similar to that of the general association between age and crime. This relationship (also known as the age-crime curve) is well-documented and follows a related pattern in different cultural contexts (Farrington 1986; Piquero 2008). One major conclusion of these findings on the age-crime curve is that criminal behavior is on the rise until the age of 16 and tends to decline after that (Sampson and Laub 2003). However, the processes leading to this initial increase and subsequent decline are hotly debated. Defining crime first and foremost as a moral action, Wikström sees personal (moral) maturation as a cornerstone in explaining the drop in criminal involvement with age. He mainly argues that with individuals developing less tolerance towards rule-breaking and being embedded in adult roles, which require them to accept general norms, they invariably become more selective with whom they associate and where. Therefore, they are exposed to fewer opportunities and circumstances in which committing a crime is considered a viable action alternative.

The timely overlap between these processes viewed through the analytical lens of SAT is the focus of the current analysis. The theory explains crime through the interaction of a person with the environment. The mechanism leading to whether an act of crime is committed or not is represented by the perception-choice process, instigated by a motivation or temptation to break a moral rule. So-called “causes of causes” (Wikström et al. 2012: 29) define the person’s properties, the environment, and the selection processes involved that lead to specific people in specific environments and specific actions. The Developmental and Ecological Action Model of SAT (DEA, Wikström 2019) links changes on the macro-, meso-, and micro-level to intra-individual changes of crime levels. This very deductive, analytical, and conclusive framework makes it appealing to empirical researchers and has promoted a rich body of literature.

Despite an accumulation of (mostly supportive) research on SAT, several scholars (e.g., Hirtenlehner and Hardie 2016; L. Pauwels et al. 2018) have criticized that the existing investigations were typically limited to particular parts of the general population. The central corpus of research has investigated children and adolescents, while only very few studies have applied SAT to more adult samples. However, if a theory claims generality, its predictions should hold in a wide variety of contexts and, at the same time, be able to also explain dynamic aspects of intra-individual development. Studies so far including at least a more heterogeneous population and conducting empirical tests on aspects of SAT are: (Antonaccio and Tittle 2008; Cochran 2015; Gallupe and Baron 2014; Eifler 2015; Piquero et al. 2016; Hirtenlehner and Hardie 2016; L. Pauwels 2018; Song and Lee 2019). Recently, Craig (2018) found evidence supporting the theory by applying it to a student sample and studying the effects on white-collar crime.

Even less research has investigated SAT’s developmental characteristics. Wikström (2009) analyzed yearly change scores for the age range from 12 to 16 to test for the theorized interaction effect between the propensity to commit crimes and criminogenic exposure to crime involvement. Bruinsma et al. (2015) analyzed the cross-lagged effects of SAT’s predictions within data of a cohort sequential design study on two cohorts of adolescents. Three waves started at ages 12 and 13, with the second wave at ages 14 and 15, and finally ending in the third wave at ages 17 and 18. Research analyzing changes from an adolescent to an adult sample with SAT is missing entirely. As a third and only very recent publication, Chrysoulakis (2020) translated DEA’s propositions concerning the connection of development in personal morality and criminogenic exposure to delinquent peers into a latent growth model (LGM)—limiting the analytical sample to three waves during early adolescence. He found that if individuals developed less tolerance towards criminal infringements, the level of criminogeneity through peers shrank and vice versa.

With regard to the empirical lack of research concerning a developmental perspective of SAT beyond adolescence, the current study applies SAT’s principle of moral correspondence within DEA as the proposed framework to analyze intra-individual changes in offending between adolescence (age 17) and adulthood (age 26). Thus, it contributes empirical evidence to an ongoing scientific debate regarding SAT’s predictions from a developmental and life-course perspective.

Situational Action Theory

P. O. Wikström introduced SAT at the beginning of the century (Wikström 2004, 2006; Wikström et al. 2012). It soon garnered support in parts of the criminological community as it claims to be a general theory of crime (Wikström 2006) and also addresses shortcomings in earlier criminological theory-building, including (1) a lack of general understanding of what crime is; (2) failure to specify an adequate action theory for crime involvement; (3) failure to explain the convergence of individual and setting; and (4) failure to analyze how the role of broader social conditions (macro-factors) shapes the process of crime causation.

SAT addresses these issues in the following manner: (1) crime is not so much defined as whether or not an action is deviant in the sense of unwritten social norms. However, acts of crime are explicitly defined as acts that break moral rules of conduct stated in law (Wikström et al. 2012: 11). Thus, SAT circumvents any discursive issues deriving from cultural contexts. (2) SAT explains the advent of action as a cognitive process leading up to it, therefore predicting criminal behavior within a given situation. Action is defined as bodily movement, or a sequence of bodily movements, under the person’s guidance and, therefore, a willful act (Wikström et al. 2012: 15). (3) The theory addresses the question of how specific people end up in specific settings. The interaction between an actor and his/her environment creates a situation that constitutes the individual’s perception of action alternatives and the process of choice (Wikström et al. 2012: 15). Finally, SAT strives for (4) integration of micro-, meso-, and macro-structures where the latter shape the conditions of the former two. Thus, they are also referred to as the “causes of the causes” (Wikström et al. 2012: 29).

In his theory’s previous tests, Wikström asserts that panel data are not necessary to test situational theories (Wikström et al. 2012). However, being a general theory, SAT needs to explain noticeable intra-individual changes in offending through time. In his Developmental Ecological Action Model of SAT (DEA) (Wikström 2019), Wikström depicts three principles of how changes on the macro-level influence the meso- and, consequently, individual offending, while the direct mechanism of crime causation at the micro-level remains stable.

As these DEA-principles reside on SAT-principles, we will turn to the latter first.

The Perception-Choice Process

In SAT, morals gain a central role in explaining crime, as “acts of crime are defined as acts that break moral rules of conduct stated in law” (Wikström et al. 2012: 11). Wikström defines a moral rule as “a rule of conduct that states what is the right or wrong thing to do (or not to do) in a particular circumstance” (ibid.). Guilt and shame enforce moral adherence within an individual. These feelings can be induced by personal reflection or through others. Therefore, according to SAT, what the right or wrong thing to do in a situation depends on the interaction of internal and external factors.

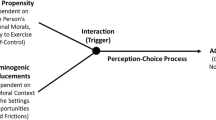

Either temptation or provocation triggers a motivation to break a moral rule, which instigates the perception-choice process. This process is initiated and guided by the interaction between a person’s crime propensity (i. e., the convergence of personal morals with corresponding moral emotions and self-control) and criminogenic exposure (i. e., settings in which the perceived moral norms and their perceived levels of enforcement or lack thereof encourage breaches of rules of conduct stated in law) (Wikström et al. 2012)Footnote 1. As the name suggests, this process involves two parts: first, a cognitive process that decides on the possible action alternatives (perception). Second, specific rules guide the process of moral choice for or against an action (choice).

In most parts of our lives, we do not consciously weigh action alternatives because most of our daily reactions in a situation are assumed to be habitual (Wikström and Treiber 2007: 246). “[H] abits are essentially created by repeated responses to familiar circumstances” (ibid.). This definition is similar to how the authors define action tendencies: “[they] refer to classes of voluntary and involuntary action that function in the service of a person’s goals, motives and concerns within any given context” (Mascolo and Fischer 2015: 118). Cognitive processes filter according to these responses and create rules of choice. A specific filter is the so-called moral filter (Wikström et al. 2012: 24) (see Fig. 1). This cognitive process determines the action alternatives an individual perceives as right or wrong in a specific setting. It balances the individual’s moral standards and the perceived morality induced by the setting. Behavioral response to a potential motivation to break a moral rule occurs in a habitual (meaning non-deliberational) manner if both the individual’s morals and the norms of the setting allow or prohibit a rule-breaking concurrently (principle of moral correspondence) (Wikström 2010: 233). Familiarity with the setting and its circumstances are vital factors that trigger habitual or deliberational action (Wikström 2009: 254).

However, suppose either the morality of the setting or the individual permits breaking a moral rule while the other prohibits that result. In that case, the moral filter fails to produce an automatic response. The individual is in a moral conflict. Subsequently, rule adherence depends on a deliberational process in which internal and external controls weigh on the decision to break a moral rule (Wikström and Treiber 2007: 245). SAT precisely predicts which control capabilities (i.e., internal or external) are relevant depending on how the moral filter failed to produce an automatic response (i.e., the principle of conditional relevance of controls): On the one hand, internal controls (e.g., self-control capabilities but also emotions such as guilt and shame) are relevant if the setting’s cues convey to the individual that giving in to the motivation can be considered a viable option, while one’s moral standards contradict that. Self-control capabilities are a specific means of adhering to one’s own moral rules in the face of adversity. On the other hand, external controls (e.g., the setting’s capability to deter somebody from breaking a moral rule) are only relevant if the individual’s morality permits the rule-breaking. In contrast, the implied setting rules contradict it (Wikström and Treiber 2007: 245).

After reviewing the mechanism by which SAT assumes crime to happen, the following section introduces the extended developmental model, which awards SAT a life-course perspective.

The Developmental Ecological Action Model (DEA)

Wikström states three principles in his Developmental Ecological Action Model (DEA) (Wikström 2019) that link macro-level changes with those on meso- and micro-levels. These principles are: (1) stability of crime involvement goes hand in hand with the processes at work in its causation; (2) the drivers for these processes are subject to psychological maturation and socio-ecological processes of social and self-selection; and (3) the explanatory processes are dependent on cultural and structural features of society (Wikström 2019: 5).

Connecting these principles with the previous outset of the theory, we can deduce that: (1) whether someone (e.g., a female) continues to see breaking a moral rule as a viable option or not and act on it is due to the same process, whether she is an adolescent or adult. This process is the perception-choice process. The causes that affect this process drive the change in criminal propensity. (2) Increasing or decreasing an individual’s likelihood to break a moral rule with age is subject only to personal maturation (or a lack thereof) and whether she (i.e., the individual) herself or her surroundings change the level of criminogenic exposure. For instance, she might start to exclusively spend time with colleagues at work who exhibit a very high level of abiding by the law. Several reasons might induce this specific association. For example, her adult self-image requires this, or her work is so time-demanding that she does not socialize with anybody else. Put more formally: on the one hand, personal maturation refers to enabling or restricting circumstances of participating in time- and place-related activities. On the other hand, the socio-ecological processes refer to preferences and agency-related choices—both within the constraints of enabling or restricting circumstances (Wikström 2019: 9). (3) The “causes of the causes” (society’s social structure) finally are the factors that shape this personal maturation and these socio-ecological processes. Social markers such as age, gender, and social class embed the individuals in their circumstances. A change in said markers rearranges the limits the circumstances impose, but it also shapes the extent to which preferences and agency develop (Wikström 2019: 9). Figure 2 emphasizes that the change processes happen on the psycho-social level for crime propensity and socio-ecological level for criminogenic exposure. In contrast, the process leading to action remains stable and is only influenced indirectly.

The drivers of stability and change in people’s crime involvement according to the DEA model of SAT (based on Wikström 2019)

For this paper’s scope, we will forego the “causes of the causes” and only focus on the predicted mechanism’s stability in the perception-choice process, personal maturity, and the underlying selection processes through time. To continue inspection of these points, we presume the following for the developmental process: with entering the period of adulthood, individuals are placed in the new roles of adults. Wikström refers to social roles in general terms as “rule- and resource-distribution-based circumstances” (Wikström 2019: 10). These new roles require adults to develop norms that instigate adherence to the law via, e.g., work ethics or responsibilities as heads of families (see Mulvey et al. 2004). Moreover, adulthood provides individuals with fewer options to enter settings with potentially criminogenic qualities via social and self-selection.

Hypotheses

Wikström and colleagues assert that “crimes tend to be committed by certain kinds of people, and to be concentrated in certain kinds of places” (Wikström et al. 2012: 323). This claim enforces the rule of moral correspondence. We can distinguish roughly two perception-choice patterns to a motivation to break a moral rule. On the one hand, certain people will find themselves more likely in situations where their personal and the perceived contextual moral rules concur (either with high or low ratings for both). We can expect a non-deliberational response with a high likelihood that could be either crime or no crime, depending on the concurrent level of each element.

On the other hand, different kinds of people will have a higher chance of being confronted with situations where personal and perceived contextual moral rules diverge. A deliberational process begins that moral emotions and both internal and external controls influence strongly. A more complex stochastic process underpins the choice for or against breaking a moral ruleFootnote 2.

Given these assumptions, we can derive three groups of people that should show either a very high, an intermediate, or a low likelihood of breaking a moral rule (i.e., committing a crime). Granted that both personal and the perceived moral context are permissive of breaking moral rules, individuals belong to the crime group, and their likelihood to commit a crime, should be the highest. Conversely, if both moral filter elements prohibit this, individuals belong to the no crime group, and their criminal tendencies, should be the lowest. A deliberation group remains in which the individuals’ personal and the perceived moral context diverge. As there is no compelling theoretical reason for the subsequent analysis to consider permissive–non-permissive or non-permissive–permissive groups separately, they will remain pooled together. The “deliberation” group’s level of criminal activity is expectedly between that of the other two groups (Hypothesis 1).

The dynamic component in DEA’s predictions are twofold: firstly, the situational mechanisms remain stable, and therefore, also our strategy to group individuals should remain stable across time. Secondly, a decline in general delinquency is attributable solely to the declining number of individuals finding themselves in morally ambiguous or crime-supporting situations. As described above, personal maturation and socio-ecological pressure to conform to moral rules are the driving forces for change. Therefore, we can expect to find more individuals in the “crime”—or “deliberation”—group at earlier stages of life (i.e., adolescence) than in later ones (i.e., adulthood). Concurrently, we expect to see a transition from criminally higher burdened groups to less burdened ones (i.e., from the “crime” to the “deliberation” or “no crime” group, and from the “deliberation” to the “no crime” group). We do not assume a sudden clustering of all individuals in the “no crime” group at age 26 because entering adulthood might reduce the risk of committing a crime but certainly does not eliminate it. It is also improbable that everyone follows the same maturation trajectory or is embedded in the same socio-ecological processes. Also, a gradual transition is more in line with a developmental/ life-course perspective. Transitions in the opposing directions are not very likely but should be observable as we are dealing with stochastic and not deterministic processes (Hypothesis 2).

Furthermore, we could assume that the likelihood to offend while belonging to the “crime” or “deliberation” group is higher during adolescence than adulthood. Given the described dynamics of change, adulthood should expose individuals less likely to settings with a motivation to break a moral rule or where they see it as a viable action alternative. In contrast, we argue that an opportunity structure, which is more appropriate for adulthood, could eventually give rise to motivations and criminogenic exposure and go hand in hand with increased offending rates. The data used for the empirical analysis provides the unique opportunity to compare rates of youth—but also adulthood—related offenses within the perception-choice process across points in time. Following SAT’s predictions of the processes’ stability, we assume that the groups’ proposed order according to their offending levels should not change given different sets of potential infringements (Hypothesis 3).

Analytic strategy

Hypothesis 1, the predicted interactional effect of peers' personal and perceived morality on crime rates, can be tested within each cross section with a logistic regression model (Agresti 2002). It estimates standard errors and also the statistical significance of a predictor. Regression weights (or in the case of logistic regression: log-odds) are estimates relative to a reference group. In our analysis, this is “no crime.” Suppose the predictions on the rate of offending per group are valid for the population. In that case, the log-odds of “crime” and “deliberation” should be statistically different from those of “no crime.” They should also indicate a higher likelihood of committing a crime. Furthermore, these weights should also reflect the proposed ordering so that being in the “crime” group corresponds with a higher risk to commit crime than being in the “deliberation” group. As in the following tests, we split the sample into male and female participants and conduct tests separately to account for the gender gap in offending (De Coster et al. 2012).

Hypothesis 2 aims to test the transitioning predictions among the three groups between points in time. While logistic models yield results for a binary outcome variable, multinomial logistic models (Agresti 2002) can consider an unordered categorical outcome with more than two categories, like our grouping variable. The grouping at age 26 is the dependent variable. These models yield standard errors and predict probabilities for transitions. The predicted transition probabilities from each group at age 17 to age 26 are estimated separately for gender and whether a person had committed a crime at age 17 and then again at age 26, providing three layers in total (see Table 6). Having an already relatively small male population, we anticipate two problems with the applied models: first, estimation problems might occur due to sparse cell distributions, leading to non-interpretable boundary values (i. e., converging towards infinity). Second, ensuing large standard errors for sparse cells require considerably large effects, which are not likely to be found, to be flagged as significant. Therefore, we will refrain from interpreting statistical tests. Instead, we describe the general trends found in the predicted probabilities. The regression results and tests of statistical inference can be found in the Appendix.

Hypothesis 3 assumes that groups’ ordering is independent of the types of crimes used for the offending scale. The logistic and multinomial logistic regression models are estimated with different crime compositions at age 26 to compare results.

Data

The German prospective panel study “Crime in the Modern City” (Crimoc; Boers et al. 2010; Seddig 2014, 2016) provides the current analysis data. It is funded by the German Research Foundation and started in 2002 with the first representative survey targeting all seventh-grade pupils in Duisburg (Germany; approximate population then: 500,000). A continuous decrease in the heavy industry characterizes the city since the 1970s. It experiences corresponding social transformations. Out of 57 schools, 40 agreed to participate in the study. 3,910 pupils remained in the sample, approximating 61% of the population of Duisburg’s seventh-grade pupils (51% male; mean age: 13.0 years). Three thousand four hundred eleven individuals participated in the first wave. The study includes 13 waves of annual (from age 20 onwards only biannual) cross-sectional surveys of respondents until 30. It spans the age period of early adolescence to early adulthood. We decided to compare our modeling results for the phases when CrimoC respondents were in their late adolescence (average age is 17) and at the end of emerging adulthood (average age is 26; Arnett 2000). Both ages mark the end of a period and a transition to another one.

From the original data of the entire panel, 1738 individuals participated at both points in time. 38% are male and 62% female. Compared to the first wave with a relatively equal distribution of gender, panel attrition led to a considerable decrease of male participants over time. By keeping the individuals equal at both times, gender will not confound the comparison’s test results. Tests within the cross section, nevertheless, will control for gender.

The design of panel studies incorporates the risk that subjects with characteristics, which researchers may be interested in, might drop out not randomly (Thornberry et al. 1993). A sensitivity analysis of how attrition in the entire panel of this study affects crime prevalences in the selected subset of waves revealed that participants of both waves reported fewer crimes at both points in time than the cross-sectional average at either wave. Consequentially, this reduces the magnitudes of effect sizes for the test of the principle of moral correspondence within the most crime-prone group while not affecting the direction of effects. The distribution of the grouping regarding the principle of moral correspondence is less affected by drop-outs. Necessarily, analyses concerning the effects of transitioning can only be conducted on those present at both points in time. In this case, we cannot empirically assess the effect of attrition. As the sensitivity results do not imply different conclusions regarding the test of the principle of moral correspondence, we draw on the selected subset as the empirical base for all analyses.

Measurements

An ideal test of SAT would take into consideration that “propensity and exposure have to come together in time and space to create an incitement to commit an act of crime” (Wikström 2009: 259). Hardie (2019) differentiates between statistical interaction (dependence) and situational interaction (convergence)—an essential differentiation of what kind of test to perform on SAT with given data and how to interpret the results. With the data for the current study, an entire model of the perception-choice process with the differential functioning of controls is not feasible, nor is it a test of convergence. However, a separate test of dependence on the rule of moral correspondence with certain restrictions is possible.

These restrictions pertain to a primary assumption that is taken for granted in general population surveys that test SAT: “Individuals with strong conforming moral beliefs generally face settings in which breaking the law is at least not normative” (Kroneberg and Schulz 2018: 62). We would further this argument by stating that the same should hold for the opposite constellation: that individuals with weak conforming moral beliefs are more likely to face settings where breaking the law is at least a viable option. Findings of studies using Space-Time Budget data support this assumption: Wikström et al. (2012) and Wikström et al. (2018) found that crime-prone people commit their criminal acts when in criminogenic settings as defined by SAT.

While the theory precisely defines personal morality (i.e., tolerance towards breaking moral rules) and has corresponding measures in the CrimoC study, we have to introduce further assumptions for a measure of criminogenic exposure, being a situational measure. Criminogenic exposure depends on the moral context of a setting, the (law-relevant) moral norms, and the potential to enforce them (Wikström et al. 2012: 141). From these three elements, we consider the moral context very significant to study the rule of moral correspondence. Originally, collective efficacy was intended to measure the moral context of a setting (Wikström et al. 2012: 143), but as the authors themselves claim, it more precisely appraises potential enforcement level.

However, Wikström (2010: 222) mentions that a “measure of the strength of a moral rule that applies to a setting is the degree to which it is shared [ … ] by those taking part in the setting”. Hardie (2019) proffered evidence that persons influence a setting not exclusively through their physical presence but also via their psychological representation in the individual’s mind. Peers can be seen as an essential reference group with whom the respondents (aged 17 and 26 years) spend a substantial portion of their leisure time. We conclude that their perceived appraisal of what is right or wrong should be a cornerstone of the perceived moral context, independent of whether they are physically present or not. Moreover, the time spent with peers in criminogenic environments is potentially higher for adolescents than for adults. However, it is reasonable to assume that adults’ embeddedness in adult roles makes them prone to take environmental cues more seriously. They are also likely to consider more seriously what others might think about their actions.

Personal moral rules/morality: Morality measures the level of tolerance towards moral rule-breaking. The scale of generalized morality in Wikström’s PADS+ study was composed of 14 moral infractions. These were categorized into minor, major, and substance use infractions. In the current study, a composite measure of six items evaluating potential wrongdoings measures generalized morality: those concerned shoplifting, assault without a weapon, provocation/intimidation, theft out of vehicle, and extortion. We excluded items (e.g., selling drugs) that showed a lack of internal consistency. The survey asked respondents: “Not every criminal act is perceived as equally serious; some are regarded as rather harmless. What do you think?” The respondents answered on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “totally harmless” (= 1) to “very bad” (= 5). Scale reliability reached alpha = 0.8 at age 17 and alpha = 0.82 at age 26.

The setting’s moral context: “[T] he moral rules that apply to the setting” (Wikström 2006: 90, originally, Wikström et al. 2012) define the moral context of the setting. We chose the measure of peers’ perceived morality over delinquent acts committed by peers, which is the more common operationalization (see Wikström et al. 2012). We followed this rationale because (1) the former represents in our understanding the internalized and perceived moral rules that apply to a setting and (2)—from a more practical point of view—the latter was only available for the survey of 26 year olds. The scale asks respondents: “What do you think, how would your friends react, if you committed one of the following acts? My friends would think [offense] to be … “. The actions under evaluation were the same offenses as in the personal moral rules scale (i.e., property damage, theft, and drug-related offenses). The response categories for the items again ranged from “totally harmless” (= 1) to “very bad” (= 5). Scale reliability reached alpha = 0.85 at age 17 and alpha = 0.84 at age 26. It is important to note that this scale may be biased: adolescents may overestimate the similarity between their and their peers’ rule-breaking behavior (Bruinsma et al. 2015).

Groups of moral correspondence: The three groups, “crime,” “deliberation,” and “no crime”, are a combination of the scales of personal morality and the perceived morality of peers. The sum scores of each are split into two parts using the scale’s midpoint as the cut-off value. We preferred this method over splitting at the median because it ascertains an equal anchoring point for both times. Furthermore, we also believe that the midpoint represents an edge to separate the groups more accurately (Kroneberg and Schulz 2018). Most people generally show less tolerance towards rule-breaking, which produces a skewed measurement. Individuals with only a relatively low tolerance (unlikely to see crime as a viable action alternative) would be conflated with those having a high tolerance (crime-prone individuals) if their score falls short of the median. Conversely, the scale’s midpoint might create less evenly distributed categories, but their distinction is more pronounced. Finally, combining two dichotomous variables yields four groups effectively, but the two ones with diverging morals (high-low or low-high) are combined into one group (deliberation), as mentioned earlier.

Crime involvement: CrimoC elicited information on a wide selection of offenses. On the one hand, there are such that already offer adolescents opportunities to break the law, such as vandalism (tagging graffiti, scratching, and general vandalism), drug-selling, property offenses (machine theft, shoplifting, bicycle theft, auto theft, theft out of vehicle, burglary, other thefts, and accepting stolen goods), and violence (aggravated assault without a weapon, aggravated assault with a weapon, purse snatching, and robbery). These will be referred to as youth crimes.

On the other hand, the study gradually elicited information on items which are more suited for an adult opportunity structure, such as traffic offenses (driving without a permit, hit and run, drunk-driving), partnership violence, work-related offenses (illegal employment, illegal advantage over employer, and illegal advantage for employer), and fraud (false claims towards insurance or public agency, tax evasion, false representation for sales of goods, selling goods without intent to deliver, fraudulent inducement to contract). These will be referred to as adult crimes. A combination of both youth and adult crimes are the total crimes. At age 17, respondents reported only about the youth crimes, at age 26, on all items.

To examine the effect of the rule of moral correspondence on crime involvement and to monitor corresponding transitions between the points in time, an aggregated index of yearly prevalence was created, measuring whether respondents had committed any of the offenses mentioned above (= 1) or none at all (= 0). For age 17, we created a scale with available youth crimes, at age 26, one for youth, adult, and total crimes. We also favor prevalence over variety or frequency scores because the current analysis focuses on whether or not people choose crime as a viable action alternative or not, rather than how intensely they commit these acts. Thus, we also circumvent complex statistical procedures for highly skewed variables.

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 and Table 2 show the distribution and correlations of key model variables. Prevalence averages at both times are below 0.2. The mean drops to 0.05 for youth crimes at age 26, but adult crimes reach approximately the same level as youth crimes during age 17. The descriptive distribution of groups among the two waves indicates an expected considerable shift from the assumedly criminally more burdened groups (“crime” and “deliberation”) to the less burdened “no crime” group.

The correlations between personal and peers’ morality are relatively strong within points in time (0.662 at age 17 and 0.736 at age 26). The concepts are also stable over time (0.484 for personal and 0.430 for peers’ morality). We also included a scale measuring peer delinquency to show that peers’ morality and this concept are strongly correlated (− 0.500). During both waves, all crime indices correlate negatively with either personal morality or morality of peers. This correlation is stronger for those aged 17 (− 0.279 and − 0.292) than those aged 26 (ranging between − 0.112 and − 0.193, depending on the scale composition).

Results for Hypotheses 1 and 3

At age 17, both males and females show a conditioning effect of the group they are assigned to relative to the “no crime” group (see Table 3). Estimates are log-odds, and their interpretation can be unwieldy. The exponentiated log-odds (i. e., odds-ratios) are easier to understand. They signify how much more or less likely the occurrence of crime is for a group relative to “no crime.” For instance, males in the “crime” group have a 4.92 higher chance of committing a crime than those in the “no crime” group.

For both genders, odds-ratios for the “crime” group are higher than for the “deliberation” group—females in the “crime” group exhibit even higher odds-ratios than their male counterparts. The exponentiated estimates of constants (0.22 for males, 0.1 for females) suggest that more males in the “no crime” group offended than females, reducing the ratio in this group, signifying the gender gap in delinquency.

At age 26, with youth crimes as the dependent variable, the constants for both genders (0.05 for males, 0.04 for females) indicate low prevalence rates for “no crime.” The separation into groups only has significance for males. Thus, the difference between the groups among females is negligible. Conversely, among males, the ordering of odds-ratios is still as predicted. The prevalence of adult crimes in the “no crime” group (0.26 for males, 0.17 for females) is relatively high. The distinction between “no crime” and the other groups is only significant for males in the “crime” group. Adult crimes—most of which could be considered less severe than those in the cluster of youth crimes—seem to be generally committed independently of the interaction between personal morality and peers’ perceived morality as operationalized with the given scales. The analysis with total crimes reflects results of the two previous ones: prevalence rates for the “no crime” group are relatively high (0.29 for males and 0.18 for females), and the distinction between groups is only significant among the male population.

In conclusion, the interaction between personal morality and peers’ perceived morality—representing SAT’s rule of moral correspondence—explains male and female offending during adolescence. Youth crimes’ prevalence rates are considerably lower during adulthood, thus reflecting DEA’s assumptions of less exposure to criminogenic environments and motivation or temptation to offend, while SAT’s assumptions still hold. However, adult crimes are more pervasive among both genders and do not follow the expected distinction among groups. This finding strongly suggests that these crimes are either so ubiquitous that the rule of moral correspondence is irrelevant, or the moral filter, as captured in the current operationalization, needs to be more granular. We will address this issue further in the Discussion section.

Results for Hypotheses 2 and 3

We split the following analysis into two parts: First, we estimate a multinomial regression model without the information of prevalence at either point in time. By omitting the information on continuity of offending and how this influences the probabilities, we can focus on the transition between groups and genders. (2) In a second step, we increase the complexity and include offending at both times. As mentioned in the Methods section, we refrain from details about model results and test outcomes and only present transition probabilities. Therefore, interpretations are strictly descriptive.

As mentioned in the previous section, the grouping procedure might not adequately capture adult crimes and the corresponding moral tolerance. Therefore, we forego to present adult or total crimes and concentrate on youth crime offending results.

Comparing distributions of groups at both times already indicated an overall shift in the expected direction from more burdened groups (“crime” and “deliberation”) to “no crime.” While these numbers are already compelling, predicted transition probabilities derived from a multinomial regression model give a more detailed analysis. As shown in Table 4, all parameters are significant except the coefficient for “crime” (26) regressed on “deliberation” (17). The regression coefficients of this type of model are hard to interpret. They can be better understood through a matrix of predicted transition probabilities, as is shown in Table 5. The mentioned non-significant parameter refers to the difference between a transition from “deliberation” (17) to “crime” (26) (probability = 0.021) and that from “no crime” (17) to “crime” (26) (probability = 0.048). This difference is non-significant.

Considering the overall movement pattern for both genders, any group transition at age 17 has the highest chance of “no crime” (probabilities from 0.974 to 0.610). Values on and below the diagonal are higher than above, which indicates that a transition to a more burdened group is possible. However, it is less likely than in the opposing direction or if individuals remain in the same group. As predicted by the gender gap in delinquency, males’ probabilities of remaining in or moving among more burdened groups are higher than females. Similarly, although relatively small, movements towards more burdened groups are more likely to occur among males than females.

Another issue concerning developmental transitions relates to how probabilities are affected if previous and current offending enter the model. Table 6 refers to these conditioned transition probabilities for youth crimes at age 26Footnote 3.

Regarding the results for males in Table 6 (prevalences for youth crimes at age 26), committing no crime at either time (0 0) coincides with the lowest chance to remain in more burdened groups or escalate towards these. For example, the chances to end in “no crime” for any group are highest in this model. Having reported an offense at least at age 26 (1 1 or 0 1) correlates with a relatively high risk of remaining in the “crime” group (0.400 and 0.500). Furthermore, continued offending (1 1) coincides with the highest chances of escalating towards or remaining in more burdened groups, supporting the claim of a conditioning effect of the rule of moral correspondence on delinquency. The two female transition patterns are similar to those of their corresponding male ones.

Given a desisting pattern (1 0), individuals of the “crime” group show a tendency to remain in this group (0.209 for males and 0.200 for females).

Discussion

At the outset of this study was the question of how self-reported measures of personal morality and perceived peer morality in a German sample reflects SAT’s rule of moral correspondence and its effect on the rate of offending. Furthermore, we looked into the theory’s developmental mechanisms by comparing where it would position individuals according to the perception-choice process at ages 17 and 26.

Three testable hypotheses were derived: (1) does a grouping of individuals according to the rule of moral correspondence coincide with the likelihood to commit crimes during either adolescence or adulthood? (2) Does the well-researched fact of declining delinquency rates after adolescence coincide with a general transition from criminally higher burdened to less burdened groups—as proposed by DEA? A positive answer to both questions would add to the validity of SAT’s and, ensuing, also DEA’s claim that a developmental process affects personal and environmental factors, while the mechanism of how these together cause breaking a moral rule remains constant. We also scrutinized the effect of repeated offending at both points in time on the transition.

(3) Concerning a shift in the opportunity structure from adolescence to adulthood to motivate a breaking of a moral rule, we compared results between scales with youth, adult, and total crimes at age 26.

Moreover, analyses were conducted separately on male and female subgroups to highlight the gender gap in delinquency.

We found strong evidence for the predicted ordering of delinquency according to SAT’s rule of moral correspondence at both times: individuals assigned to the “crime” group exhibit the highest rate of offending for youth crimes, followed by the “deliberation” and finally by the “no crime” group. Although—according to the gender gap in delinquency—the levels of offending rates differed between genders, this did not affect the outcome of how the proposed mechanism caused offending at age 17. Because women barely committed any youth crimes at age 26, we lacked sufficient data to confirm this finding for both genders in all possible offending combinations.

Adult crime rates at age 26 exceed levels of youth crime offending at age 17 for both genders. However, the grouping did not generally condition offending rates as predicted by the rule of moral correspondence. A moral filter at age 26, which focuses on the moral tolerance towards youth crimes exclusively rather than also including adult crimes, could be the reason. At the outset of the study, we had to weigh two factors against each other. On the one hand, continuity in understanding the measured constructs (personal morality and that of peers) over time would ensure that the grouping would have a comparable validity at both times. Suppose a construct’s measurement is sensitive to how individuals perceive the underlying scale divergently over time instead of assigning them to different groups according to substantial changes. In that case, the measurement deals with issues of reliability. Including the same set of items is a precondition for that type of reliability.

On the other hand, the meaning of constructs might shift when former attributes lose their salience for respondents, while others, previously not important attributes, become salient. In our case, it could be argued that morality in adulthood encompasses a broader range of potential moral rules to be broken than during adolescence. However, the scale composition would change between points in time, and measurement properties might again confound assignment to groups due to substantial changes.

Nonetheless, we can conclude that attributes of the moral filter and moral infringements ought to comply. Future studies, which look into changes between adolescence and adulthood through the lens of SAT, need to address continuity of measurements.

The transition between the points in time followed the expected pattern of individuals moving from more criminally burdened groups (“crime” and “deliberation”) to less burdened ones (“deliberation” and “no crime”). We could also detect escalating transitions moving in the opposite direction and individuals remaining in those more burdened groups. However, those exhibited relatively low likelihoods, a result shared by both genders.

The additional information on the offense patterns over time confirmed the expectation that offending coincides with higher chances for remaining or escalating patterns than offending at no time. With the limited size of cells for men (and partly none for women), the separation into layers of offense patterns brought no clear insights that would supplement the logistic regression results on the conditioning effect of the rule of moral correspondence. However, keeping the small sample size among the male group in mind, the results tentatively suggest that continuing offenders do not only have higher chances than total abstainers for a remaining or escalating pattern. They are also higher than for those who offended only once, thus further supporting the claims of the rule of moral correspondence.

The current study provides the more practical insight that personal moral maturation is an empirical trend in a population of adolescents transitioning to adulthood. If we are willing to take self-reports on peers’ moral status at their face value, the results also suggest a corresponding decrease in criminogenic exposure. However, at age 26, a non-negligible portion of study participants remain in morally criminogenic personal patterns or are exposed to morally “tolerant” peers (“deliberation” group, n = 118), or experience a coupling of both factors (“crime” group, n = 46). Twenty-six years, after all, is still merely the end of “emerging” adulthood. Most certainly, not all individuals will have found stable adult roles, further reducing the risks to offend.

The data provided by CrimoC limited the model of the perception-choice process to the rule of moral correspondence while omitting the rule of differential control due to a lack of adequate measures for the controls. Furthermore, we presented results for a person-centered analysis rather than a situational one, which would be the preferred method for a situational theory. Nevertheless, our results are robust and in line with previous research on regular survey data, which shows the theory's utility beyond a strict situational interpretation.

An explicit limitation of the current analysis is that we did not model the “causes of the causes” leading to positioning at a point in time and transitioning across time. Ensuing research questions could be: Why do specific individuals follow an escalating or remaining pattern? Are endowed childhood and correlated psychological factors responsible, or rather factors acquired through social and personal agency causally related, or is a conflation of both the driving force behind these developments? We also merely looked at two points in time with a span of nine years in between. What happens during this period? For instance, how do experiences with adult roles (e. g., partnership, education, social embeddedness, employment) reflect on transitions?

Conclusion

The DEA model of SAT theoretically combines macro-, meso-, and micro-level factors to explain the advent or absence of crime coherently. Hence, it serves as a highly integrative analytical framework also applicable to non-situational data. We could find empirical evidence for both SAT’s and DEA’s predictions. On the one hand, the interaction of personal and environmental criminogenic factors is a valuable empirical predictor of criminal involvement during adolescence and emerging adulthood. On the other hand, our analyses found evidence supporting developmental processes in both rates of delinquency and associated factors as predicted by DEA.

However, these results only point to the simultaneity of (predicted) co-occurring events. They are no definitive causal test of exogenous factors influencing delinquency and the mechanisms that causally affect it. Thus, we encourage future research to (a) find further empirical evidence for or against the theoretically predicted macro- and meso-level factors influencing the proposed causal mechanism of delinquency. But future analyses should also go beyond by (b) modeling the implied causal structure with longitudinal research designs, which can separate causal from co-occurring factors on the different levels of aggregation.

Availability of Data and Material

Data, the code for data transformation, and the code for the statistical analyses can be provided on demand by the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

More precisely, Wikström defines criminogenic exposure "as dependent on their time spent unsupervised with peers in areas with poor collective efficacy and their friends' crime involvement" (ibid.: 253)

We would like to point out that this depiction of only two categories for each element is the simplest way to represent the moral filter, rather than three categories (high, medium, and low) or even the continuous case. This reduction in complexity comes at the cost of losing variance and the opportunity to model the underlying processes more finely grained. Conversely, results are much easier to interpret and understand.

Table 6 lacks two models for the female part, caused by empty cells for females with the offending patterns (1 1 and 0 1).

References

Agresti, A. (2002). Categorical data analysis (Second ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0025540896800183.

Antonaccio, O., & Tittle, C. R. (2008). Morality, self-control, and crime. Criminology, 46(2), 479–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00116.x.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Boers, K., Reinecke, J., Seddig, D., & Mariotti, L. (2010). Explaining the development of adolescent violent delinquency. European Journal of Criminology, 7(6), 499–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370810376572.

Bruinsma, G., Pauwels, L., Weerman, F., & Bernasco, W. (2015). Situational action theory: Cross-sectional and cross-lagged tests of its core propositions∖. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 57(3), 363–398. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2013.E24.

Chrysoulakis, A. P. (2020). Morality, delinquent peer association, and criminogenic exposure: (How) does change predict change? European Journal of Criminology., 147737081989621. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819896216.

Cochran, J. K. (2015). Morality, rationality and academic dishonesty: A partial test of situational action theory. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 4(813), 192–199.

Craig, J. M. (2018). Extending situational action theory to white-collar crime. Deviant Behavior, 40, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1420444.

De Coster, S., Heimer, K., & Cumley, S. R. (2012). In F. T. Cullen & P. Wilcox (Eds.), Gender and theories of delinquency. Oxford University Press.

Eifler, S. (2015). Situation und Kontrolle : eine Anwendung der Situational Action Theory auf Gelegenheiten zur Fundunterschlagung. Monatsschrift Für Kriminologie Und Strafrechtsreform, 98(3), 227–256.

Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. Crime and Justice, 7(January), 189–250.

Gallupe, O., & Baron, S. W. (2014). Morality, self-control, deterrence, and drug use: Street youths and situational action theory. Crime and Delinquency, 60(2), 284–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128709359661.

Hardie, B. (2019). Why monitoring doesn’t always matter: The interaction of personal propensity with physical and psychological parental presence in a situational explanation of adolescent offending. Deviant Behavior, 42, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1673924.

Haynie, D. L., & Wayne Osgood, D. (2005). Reconsidering peers and delinquency: How do peers matter? Social Forces, 84(2), 1109–1130.

Hirtenlehner, H., & Hardie, B. (2016). On the conditional relevance of controls: An application of situational action theory to shoplifting. Deviant Behavior, 37(3), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2015.1026764.

Kroneberg, C., & Schulz, S. (2018). Revisiting the role of self-control in situational action theory. European Journal of Criminology, 15(1), 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817732189.

Mascolo, M. F., & Fischer, K. W. (2015). The dynamic development of thinking, feeling, and acting over the life span. In W. Overton & P. C. M. Molenaar (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Theory and Method (7th ed., pp. 113–161). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

Matsueda, R. L., & Anderson, K. (1998). The dynamics of delinquent peers and delinquent behavior. Criminology, 36(2), 269–308.

Mulvey, E. P., Steinberg, L., Fagan, J., Cauffman, E., Piquero, A. R., Chassin, L., Knight, G. P., et al. (2004). Theory and research on desistance from antisocial activity among serious adolescent offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(3), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204004265864.

Pauwels, L. (2018). The conditional effects of self-control in situational action theory. A preliminary test in a randomized scenario study. Deviant Behavior, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1479920.

Pauwels, L., Svensson, R., & Hirtenlehner, H. (2018). Testing situational action theory: A narrative review of studies published between 2006 and 2015. European Journal of Criminology, 15(1), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817732185.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In The Long View of Crime: A Synthesis of Longitudinal Research (pp. 23–78). New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71165-2_2.

Piquero, A. R., Bouffard, J. A., Piquero, N. L., & Craig, J. M. (2016). Does morality condition the deterrent effect of perceived certainty among incarcerated felons? Crime and Delinquency, 62(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128713505484.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2003). Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys followed to age 70. Criminology, 41(3), 555–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb00997.x.

Schoepfer, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2006). Self-control, moral beliefs, and criminal activity. Deviant Behavior, 27(1), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/016396290968326.

Seddig, D. (2014). Peer group association, the acceptance of norms and violent behaviour: A longitudinal analysis of reciprocal effects. European Journal of Criminology, 11(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370813496704.

Seddig, D. (2016). Crime-inhibiting, interactional and co-developmental patterns of school bonds and the acceptance of legal norms. Crime & Delinquency, 62(8), 1046–1071. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128715578503.

Sherif, M., & Sherif, C. W. (1964). Reference groups: exploration into conformity and deviation of adolescents. New York: Harper & Row.

Song, H., & Lee, S.-S. (2019). Motivations, propensities, and their interplays on online bullying perpetration: A partial test of situational action theory. Crime & Delinquency, 001112871985050, 1787–1808. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719850500.

Thornberry, T. P., Bjerregaard, B., & Miles, W. (1993). The consequences of respondent attrition in panel studies: A simulation based on the Rochester youth development study. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 9(2), 127–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01071165.

Vazsonyi, A. T., Pickering, L. E., Junger, M., & Hessing, D. (2001). An empirical test of a general theory of crime: A four-nation comparative study of self-control and the prediction of deviance. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38(2), 91–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427801038002001.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Warr, M., & Stafford, M. (1991). The influence of delinquent peers: What they think or what they do? Criminology, 29(4), 851–866.

Wikström, P. O. (2004). Crime as alternative: Towards a cross-level situational action theory of crime causation. In J. McCord (Ed.), Beyond Empiricism: Institutions and Intentions in the Study of Crime (Vol. 13, pp. 1–37). Routledge.

Wikström, P. O. (2006). Individuals, settings, and acts of crime: situational mechanisms and the explanation of crime. In P.-O. H. Wikström & R. J. Sampson (Eds.), The Explanation of Crime (pp. 61–107). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489341.004.

Wikström, P.-O. H. (2009). Crime propensity, criminogenic exposure and crime involvement in early to mid adolescence. Monatsschrift Für Kriminologie Und Strafrechtsreform, 92(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1515/mks-2009-922-312.

Wikström, P. O. (2010). Explaining Crime as Moral Actions. In S. Hitlin & S. Vaisey (Eds.), Handbooks, Handbook of the Sociology of Morality (pp. 211–239). New York: Springer.

Wikström, P. O. H. (2019). Explaining crime and criminal careers: the DEA model of situational action theory. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 6, 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-019-00116-5.

Wikström, P. O. H., & Treiber, K. (2007). The role of self-control in crime causation: Beyond Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. European Journal of Criminology, 4(2), 237–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370807074858.

Wikström, P.-O. H., Oberwittler, D., Treiber, K., & Hardie, B. (2012). Breaking rules. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wikström, P. O. H., Mann, R. P., & Hardie, B. (2018). Young people’s differential vulnerability to criminogenic exposure: Bridging the gap between people- and place-oriented approaches in the study of crime causation. European Journal of Criminology, 15(1), 10–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817732477.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The German Research Foundation fully funds the study Crime in the Modern City (CrimoC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kessler, G., Reinecke, J. Dynamics of the Causes Of Crime: a Life-Course Application of Situational Action Theory for the Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood. J Dev Life Course Criminology 7, 229–252 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00161-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00161-z