Abstract

This paper examines the role of monetary factors in the variation of nominal interest rates in India for the deregulated regime of interest rates and the exchange rates. Empirical analysis involves quarterly time series dataset including interest rates on 91-day, 364-day treasury bills (TBs), call money rate, money supply (both narrow and broad money), income and exchange rate over the period 1996–97:Q1 to 2015–16:Q4. In the short-run and the long-run variations of interest rates on TBs, role of the broad money supply, income and exchange rate are established; where the broad money negatively affects interest rates indicating the Liquidity effect view. Income and depreciation of exchange rate lead to raise interest rates. In the variations of the call money rate income, the narrow money and the broad money have significant role but the role of exchange rate is not established. The paper also finds evidence that interest rates on TBs are related to the relative growth of money supply and anticipated nominal income. Theatrical base of such relation is discussed based on some seminal work of Friedman. Based on these findings the paper concludes that it would be effective to control interest rate through a comprehensive monetary management.

Source: Author’s estimation

Source: Author’s estimation

Source: Author’s estimation

Source: Author’s estimation

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ahmad, M., and M.Z.A. Karim. 2011. Interest Rate Determination and the Effect of Asian Financial Crisis in Malaysia. The IUP Journal of Applied Economics 10 (1): 37–54.

Ahn, B.C. 1994. Monetary Policy and the Determination of the Interest Rate and Exchange Rate in a Small Open Economy with Increasing Capital Mobility. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper Series No. 024A. St. Louis, MO: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Aksoy, Y. and M.A. León-Ledesma. 2005. Interest Rates and Output in the Long-Run. Working Paper, No. 434/January 2005, European Central Bank.

Amarasekara, C. 2005. Interest Rate Pass-through in Sri Lanka. Staff Studies, Central Bank of Sri Lanka 35 (1 & 2): 1–32. doi:10.4038/ss.v35i.1232.

Ball, L. 1999. Efficient Rules for Monetary Policy’. International Finance 2 (1): 63–83. doi:10.1111/1468-2362-00019.

Bernanke, B.S., and I. Mihov. 1998. The Liquidity Effect and Long-Run Neutrality. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 49: 149–194.

Batini, N., R. Harrison, and S. Millard, 2001. Monetary Policy Rules for Open Economies. Bank of England Working Paper, No. 149. Bank of England, 2001.

Barro, Robert J. 1974. Are Government Bonds Net Wealth. Journal of Political Economy 82 (6): 1095–1117. doi:10.1086/260266.

Bhanumurthy, N.R., and S. Agarwal. 2003. Interest Rate-Price Nexus in India. Indian Economic Review 38 (2): 189–203.

Bhattacharya, B.B., N.R. Bhanumurthy, and H. Mallick. 2008. Modeling Interest Rate Cycle in India. Journal of Policy Modeling 30(5): 899–915. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2007.03.004.

Brown, R.L., J. Durbin, and J.M. Evans. 1975. Techniques for Testing the Constancy of Regression Relations over Time. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 37 (2): 149–192.

Chakraborty, L.S. 2012. Interest Rate Determination in India: Empirical Evidence on Fiscal Deficit –Interest Rate Linkages and Financial Crowding Out, Working Paper No. 744, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson.

Cooray, A. 2002. Interest Rates and Inflationary Expectations: Evidence on the Fisher Effect in Sri Lanka. South Asia Economic Journal 3 (2): 201–216. doi:10.1177/139156140200300205.

Dickey, D.A., and W.A. Fuller. 1981. Likelihood Ratio Statistics for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Econometric 49 (4): 1057–1072.

Dua, P., and B.L. Pandit. 2002. Interest Rate Determination in India: Domestic and External Factors. Journal of Policy Modeling 24 (8): 853–875. doi:10.1016/S0161-8938(02)00172-2.

Dua, P., N. Raje, and S. Sahoo. 2003. Interest Rate Modeling and Forecasting in India, Development Research Group, Study No. 24, Department of Economic Analysis and Policy, Reserve Bank of India.

Edwards, S., and M.S. Khan. 1985. Interest Rate Determination in Developing Countrie. IMF Staff Papers 32 (3): 377–403. doi:10.3386/w1531.

Engel, Charles. 1996. The Forward Discount Anomaly and the Risk Premium: A Survey of Recent Evidence. Journal of Empirical Finance 3 (2): 123–192.

Engel, Charles. 2014. Exchange Rate and Interest Rate Parity. In Handbook of International Economics, eds. Gita Gopinath and Elhanan Helpman, vol. 4, 453–522. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-54314-1.00008-2.

Fisher, I. 1930. The Theory of Interest. New York: Macmillan.

Friedman, Milton. 1969. The Optimum Quantity of Money, and Other Essays, 1969. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.

Friedman, Milton. 1970. A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis. Journal of Political Economy 78 (2): 193–238.

Friedman, Milton. 1971. A Monetary Theory of Nominal Income. Journal of Political Economy 79 (2): 323–337.

Friedman, Milton 1971. The Keynesian Challenge to the Quantity Theory, NBER Chapters. In A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis, 15–29. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Gale, W.G., and P.R. Orszag. 2003. The Economic Effect of Long-Term Fiscal Discipline, Discussion Paper No. 8, April 2003. The Urban Institute, Washington, DC.

Gochoco, M.S. 1991. Financial Liberalization and Interest Rate Determination: The case of the Philippines, 1981–1985. Journal of Macroeconomics 13(2): 335–350. doi:10.1016/0164-0704(91)90060-8.

Goh, S.K. and M. H. Alias. 2002. Malaysia Financial Liberalization and Crisis: Reflections on National Responses. In Monetary and Financial Management in Asia in the 21st Century, ed. Augustine H.H. Tan, 191–211. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Hussin, A.A., N.T. Hee, and A. Razi. 1993. Financial Liberalisation and Interest Rate Determination in Malaysia. Bank Negara Malaysia Discussion Papers No. 12. Kuala Lumpur: Bank Negara Malaysia.

Jha, R. 2002. Downward Rigidity of Indian Interest Rates. Economic and Political Weekly 37 (5): 469–474.

Keynes, J.M. 1936.The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan Cambridge University Press, for Royal Economic Society in 1936.

Leeper, E.M. and D.B. Gordon. 1991. In Search of the Liquidity Effect, International Finance Discussion Paper, No. 403, July, 1991, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Mohanty, D. 2012. Evidence of Interest Rate Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission in India. RBI Working Paper Series, WPS (DEPER): 6/2012.

Maitra, B. 2016. Monetary, Real Shocks and Exchange Rate Variations in India. Journal of Economic Development 41 (1): 81–102.

Monnet, C., and W.E. Weber. 2001. Money and Interest Rates. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 25 (4): 2–13.

Nachane, D.M. 1988. The Interest-Price Nexus: An old theme Revisited. Economic and Political Weekly 23 (9): 421–424.

Obstfeld, M., and K. Rogoff. 1995. The Mirage of Fixed Exchange Rates. Journal of Economic Perspective 9 (4): 73–96.

Obstfeld, M. 2015. Trilemmas and Tradeoffs: Living with Financial Globalization, BIS Working Paper, No. 480. Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements.

Paul, M.T. 1984. Interest Rates and Fisher Effect in India. Economic Letters 14 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(84)90022-3.

Pesaran, M. Hashem, Y. Shine, and R.J. Smith. 1999. Bound Testing Approach to the Analysis of Long-Run Relationships. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics, 9907, Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge.

Pesaran, M.Hashem, Y. Shine, and R.J. Smith. 2001. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16 (3): 289–326.

Phillips, P.C.B., and P. Perron. 1988. Testing for a Unit Root in a Time Series Regression. Biometrika 75 (2): 335–346.

Sathye, M., D. Sharma, and S. Liu. 2008. The Fisher Effect in an Emerging Economy: The Case of India. International Business Research 1 (2): 99–104.

Schabert, A. 2005. Money Supply and the Implementation of Interest Rate Targets. Working Paper Series, No. 483, May 2005. European Central Bank.

Svensson, Lars E.O. 2000. Open-Economy Inflation Targeting. Journal of International Economics 50 (1): 155–183. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00078-6.

Taylor, John B. 1999. Robustness and Efficiency of Monetary Policy Rules as Guidelines for Interest Rate Setting by the European Central Bank. Journal of Monetary Economics 43 (3): 655–679. doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(99)00008-2.

Taylor, John B. 2001. The Role of the Exchange Rate in Monetary-Policy Rules. American Economic Review 91 (2): 263–267. doi:10.1257/aer.91.2.263.

Thornton, D.L. 2012. Monetary Policy: Why Money Matters and Interest Rates Don’t. Working Paper, No. 2012-020A, Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Turtelboom, B. 1991. Interest Rate Liberalization: Some Lessons from Africa. IMF Working Paper, No. WP/91/121, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Reviewer(s) of the journal for some valuable comments which help to improve the paper. I also would like to thank Professor C. K. Mukhopadhyay (Retd.) of University of North Bengal, India, Professor Gunther Rehme of Technische Universitat Darmstadt, Germany and Dr. P.K. Das of CSSSC, Calcutta who commented on an earlier version of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

How Nominal Interest Rates are Related to the Relative Growth of Money supply and Anticipated Nominal Income?

Theoretical relation that nominal interest rate is related to the relative growth of money supply and anticipated nominal is has been presented in this section. This theoretical exposition is mainly based on some seminal work of Milton Friedman such as Friedman (1969): ‘The Optimum Quantity of Money, and Other Essays’; Friedman (1970): ‘A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis’; Friedman (1971): ‘A Monetary Theory of Nominal Income’; Friedman (1971): ‘The Keynesian Challenge to the Quantity Theory’.

Friedman view that Keynesian interest rate theory is not a complete theory as it fails to explain empirical phenomena concerning movement of interest rate following changes in money supply. Specifically, Keynesian interest rate theory cannot explain situations where interest rate displays positive response to money supply variations. Again, the Fisher equation fails to explain negative sensitivity of interest rate to money supply. He proceeds to reformulate the interest equation which essentially integrates the fundamental mechanism and reality in Keynesian interest rate theory with the macroeconomic exposition of microeconomic decision as manifested through the Fisher equation of interest rate.

To explain this, let us consider a money demand and a money supply functions are \(\hbox {M}^{\mathrm {D}}=\hbox {l}\left( \hbox {i} \right) \hbox {Y}\left( {\mathrm{t}} \right) \) and \(\hbox {M}^{\mathrm {s}}=\hbox {M}\left( {\mathrm{t}} \right) \) respectively:

where \(\hbox {Y}\left( {\mathrm{t}} \right) \) is the nominal income at time period ‘t’, \(\hbox {l}\left( \hbox {i} \right) \) is the coefficient of cash-balance demand, \(\hbox {M}\left( {\mathrm{t}} \right) \) money supply at time ‘t’, \(\hbox {V}\left( \hbox {i} \right) \) is the velocity of money, (which is not a constant, its variation is linked to that in interest rate). Therefore, given \(\hbox {V}\left( \hbox {i} \right) ,\) and \(\hbox {M}\left( {\mathrm{t}} \right) \) in any economy at any period (t), the nominal income is determined.

Friedman starts with the Fisher’s interest rate equation which is:

where \(\hbox {i}_{\mathrm{t}} \) is the nominal interest rate, \(\hbox {r}_{\mathrm{t}} \) is the real interest rate, \({\uppi }_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \) is the expected inflation.

He then seeks to explain \({\pi }_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \). He holds that

where \(\hbox {X}_{\mathrm{t}} \) is the real income, \(\hbox {Y}_{\mathrm{t}} \) is the nominal income, \(\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{t}} \) is the price level

He holds further that the real income (\(\hbox {X}_{\mathrm{t}} )\) and price level (\(\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{t}} )\) are determined through two independent processes. Consequently, \(\hbox {X}_{\mathrm{t}} \) and \(\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{t}}\) are independent such that:

where \(\hbox {X}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \) is the expected real income, \(\hbox {Y}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \) is the expected nominal income, \(\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \) is the expected price level.

Taking log

Differencing with respect to ‘t’ we have,

Equation (5) indicates that expected inflation rate is the difference between the expected rate of growth of nominal income and the expected rate of growth of real income. Now, putting (5) into (3) we have,

Friedman holds that, because of money illusion, people usually expect real income growth to remain constant, and nominal income growth to undergo changes. Consequently given \(\hbox {r}_{\mathrm{t}} \), we have a constant value for \(\hbox {x}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \).

Thus, \(\hbox {r}_{\mathrm{t}} -\hbox {x}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} =\hbox {k}\) (constant)

In such case from Eq. (6) we have,

Thus, the nominal interest rate (\(\hbox {i}_{\mathrm{t}} )\) is the sum of a constant and a rate of nominal income growth.

Friedman uses the adaptive expectation hypothesis for the determination of \(\hbox {y}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \). He holds that the change in the expected rate of growth of nominal income (\(\hbox {dy}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} )\) in proportion to the deviations of the observed from the anticipated rate of growth. This indicates that expectations are adjusted to the forecast error. A part of forecast error is taken into the reformulation of anticipated value of nominal income growth. Consequently,

Variations in Interest Rates due to Change in Money Growth and Anticipated Income Growth

According to Friedman, the fall or rise of interest rate depends on the rate of growth of money supply and rate of growth of anticipated income. To show this, differentiating Eqs. (7) and (8) with respect to ‘t’ we have,

Case 1: When Money Growth is Greater than Expected Income Growth

When \(\hbox {m}>\dot{\hbox {y}}^{e}_{t}\) then \(\hbox {y}_{\mathrm{t}} >\hbox {y}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} \), consequently, \(\frac{\hbox {dy}_{\mathrm{t}}^{\mathrm{e}} }{\hbox {dt}}>0\) [from Eq. (10)]. Therefore, from Eq. (9) we have \(\frac{\hbox {di}_{\mathrm{t}} }{\hbox {dt}}>0\) . So, it indicates that interest rate will rise over time when money supply growth rate rises provided that the rate of growth of money supply exceeds the rate of growth of nominal income.

Case 2: When Money Growth is Equal to Expected Income Growth

Here we have found that interest rate remains unchanged following money supply when the rate of growth of money supply is equal to the rate of nominal income.

Case 3: When Money Growth is Less than the Expected Income Growth

It is also proved that interest rate will fall following increase in money supply when the rate of growth of money supply lags behind the rate of growth of anticipated nominal income.

Therefore, a fall or a rise of interest rate depends on the rate of growth of money supply and rate of growth of anticipated income where interest rate rises when money growth rate rises provided that the rate of growth of money supply exceeds the rate of growth of nominal income. Conversely, interest rate falls following increase in money supply when the rate of growth of money supply lags behind the rate of growth of anticipated nominal income and, in fact, interest rate remains unchanged following money supply when the rate of growth of money supply is equal to anticipated nominal income.

Appendix B

Estimation of Anticipated nominal Income Through ARIMA Forecasting

It is found that seasonally adjusted nominal income series has followed ARIMA [(1, 2), 1, 0) process which is estimated and presented in Eq. (11).

DW = 1.958, F-Statistic = 7.685 (prob. 0.00), Log likelihood = 151.12, AIC = −3.847, SC = −3.756

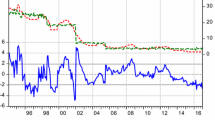

Time plots of the ARIMA forecast (or anticipated nominal income) series of income with the actual series of income has been presented in Fig. 8. Correlogram of the ARIMA residual series is presented in Fig. 9 which indicates that the forecast residuals are white noise.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maitra, B. Determinants of Nominal Interest Rates in India. J. Quant. Econ. 16, 265–288 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-017-0079-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-017-0079-2