Abstract

While formative assessments (FAs) can facilitate learning within undergraduate STEM courses, their impact likely depends on many factors, including how instructors implement them, whether students buy-in to them, and how students utilize them. FAs have many different implementation characteristics, including what kinds of questions are asked, whether questions are asked before or after covering the material in class, how feedback is provided, how students are graded, and other logistical considerations. We conducted 38 semi-structured interviews with students from eight undergraduate biology courses to explore how various implementation characteristics of in-class and out-of-class FAs can influence student perceptions and behaviors. We also interviewed course instructors to provide context for understanding student experiences. Using thematic analysis, we outlined various FA implementation characteristics, characterized the range of FA utilization behaviors reported by students, and identified emergent themes regarding the impact of certain implementation characteristics on student buy-in and utilization. Furthermore, we found that implementation characteristics have combined effects on student engagement and that students will tolerate a degree of “acceptable discomfort” with implementation features that contradict their learning preferences. These results can aid instructor reflection and guide future research on the complex connections between activity implementation and student engagement within STEM disciplines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Formative assessment (FA) has been heralded as one of the most effective ways to improve student learning (Black & Wiliam, 1998), and the addition of in-class and out-of-class FA activities to undergraduate courses can improve student performance and reduce failure rates within STEM courses (Freeman et al., 2007, 2014). Many sources define FAs as tasks that occur during the learning process with the intended purpose of improving learning (assessment for learning) rather than assigning grades (assessment of learning; Angelo & Cross, 1993; Chappuis & Stiggins, 2002; Sadler, 1998). Despite their potential, there can be wide variation in how instructors implement FA activities and how students interact with them, which could explain the variation seen in resulting student learning in STEM courses (Andrews et al., 2011; Freeman et al., 2014; Turpen & Finkelstein, 2010). For this reason, recent FA meta-analyses have highlighted the need for research to define and understand how task characteristics influence FA effectiveness (Dunn & Mulvenon, 2009; Kingston & Nash, 2011). In the current study, we explore how different FA implementation characteristics affect student perceptions and utilization behaviors as a starting point for understanding how connections between instructor and student components shape FA learning outcomes.

Background Theory and Theoretical Framework

As a backdrop for investigating how instructor-based FA elements impact student engagement, we highlight various theories that relate to how FA activities facilitate learning. FAs build upon the proposition that growth stems from the creation of cognitive conflict in the learner through realization of incorrect conceptions (Vygotsky, 1978). FAs allow instructors to guide students in the zone of proximal development, where students can make developmental advancements with the aid of instructional supports. FAs place a strong emphasis on collaborative learning and social construction in which nascent ideas are encountered first in a group context prior to incorporation by the individual (Slavin, 1996). Finally, FAs depend on and cultivate metacognition and self-regulated learning, as the learner diagnoses their understandings and refines their actions in service of their achievement goals (Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Hacker et al., 1998). In relation to these broader principles, FAs serve to create “moments of contingency” in which the instructor and student can cultivate learning (Black & Wiliam, 2009).

Building on these broader learning theories, Black and Wiliam (2009) proposed the theory that FAs promote learning by achieving five objectives. (1) FAs help clarify learning intentions and criteria for success by providing students with sample tasks that communicate what students are expected to know and be able to perform. (2) FAs elicit evidence of student understanding through their answers to question prompts. (3) FAs provide feedback that moves learners forward by helping them to correct and expand their understandings. (4) FAs activate students as instructional resources for one another through peer discussion and group work. (5) FAs enable students to take ownership of their learning by equipping them with tools and processes that support growth.

Black and Wiliam’s theory behind how FAs promote learning represents an idealized form of the FA process. In reality, instructors design activities in ways that support the five objectives to varying degrees, and students participate in the activities in different ways, which together impact whether beneficial “moments of contingency” occur. Thus, there remains a need to understand connections between how instructors implement FA activities and how students respond to them. In other words, we need to better characterize the intricate ways in which FA activity design and implementation may or may not lead students to employ productive learning behaviors.

Investigating FA implementation thus requires a theoretical framework that situates the roles of instructors and students in the FA process. Prosser and Trigwell (2014) outlined a broad model of teaching and learning showing the complex relationships between instructor-level and student-level factors that influence learning outcomes. Within this overarching model, the pathway wherein teaching practices affect student perceptions, which influence how students approach learning and the resulting learning outcomes, provides a useful lens for understanding the effects of FA implementation. We adapted these components to develop the theoretical framework for the current study. In our FA Engagement Framework (Fig. 1), FA implementation characteristics affect student perceptions about the activity (i.e., buy-in). During this process, students evaluate aspects of the FA assignment to decide how the activity relates to their course goals. These judgments then shape how the student behaves during and after the activity (i.e., utilization), prompting them to leverage the activity in a way that aligns with their goals. FA engagement (i.e., buy-in and utilization) then influences subsequent learning by determining the cognitive processes that students employ. The following three sections present the conceptual framework guiding our study.

The FA Engagement Framework situates the roles of instructors and students in the FA process. On the instructor side, implementation characteristics represent how the instructor designs and delivers an FA within a course, which shapes student experiences (top arrow). On the student side, student buy-in regarding the value of the activity influences the utilization behaviors they exhibit with respect to the activity. Ultimately, the product of student buy-in and utilization (i.e., engagement) dictates resulting learning outcomes. In the longer term, understanding how students engage with an FA assignment provides instructors with information they can use to improve activity implementation (bottom arrow)

Background Literature

FA Implementation Characteristics

Instructor implementation encompasses the many aspects of how the instructor designs and delivers an FA within a course, including structural features and practical considerations. Reviews of FA implementation have largely drawn from learning theories, studies connected to learning gains, and instructor-reported best practices (Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991; Black & Wiliam, 2009; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Offerdahl et al., 2018; Shute, 2007) but to a lesser extent on how students perceive and respond to implementation characteristics (Gibbs, 2010). These reviews have identified several general recommendations, such as distributing assessments throughout the term, targeting assessments toward clear and high criteria, and providing specific feedback that promotes learning goal orientation. Research-based recommendations applicable to STEM courses have emerged for in-class FAs, such as Peer Instruction with clickers (Knight & Brame, 2018; Vickrey et al., 2015), cooperative group work (Oakley et al., 2004; Tanner et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2018), and in-class active learning (Eddy, Brownell, et al., 2015a), but less attention has been paid to out-of-class FAs for undergraduate STEM courses (Letterman, 2013). A prior review on formative feedback called attention to the idea that FA features can have combined effects, in which one characteristic influences the effect of other characteristics (Shute, 2007). This has important consequences for instructors and researchers because it elevates the need to consider FAs as complex entities, with each activity consisting of an array of underlying characteristics.

Student Buy-In Toward FAs

Most previous research on student perceptions of FAs has targeted in-class activities, such as clicker questions and cooperative group work. Some studies from STEM disciplines report overall positive reactions to these techniques (Ernst & Colthorpe, 2007; Vickrey et al., 2015; Winstone & Millward, 2012), while studies from a broader array of disciplines find more negative reactions, particularly toward cooperative group tasks and discussions, compared with attitudes toward traditional lecture (Lake, 2001; Machemer & Crawford, 2007; Phipps et al., 2001; Struyven et al., 2008). Additional research in STEM contexts indicates positive undergraduate student perceptions of out-of-class FAs, such as Just-in-Time Teaching and other homework assignments (Freasier et al., 2003; Jensen et al., 2015; Novak, 2011; Parker & Loudon, 2013). Importantly, many studies of student perceptions focus on general measures of satisfaction or helpfulness and do not directly examine how students perceive the FA to influence their learning or what implementation characteristics students find most useful.

In contrast, our prior survey-based studies in biology examined a range of in-class and out-of-class FAs and focused on student buy-in, defined as the extent to which a student recognizes and values how a method helps their learning. We found that many undergraduate biology students perceive FAs to improve their learning by achieving one or more of the five FA objectives (Brazeal et al., 2016). In addition, we found that higher buy-in toward FAs predicts higher exam and course performance, even after controlling for other student achievement and demographic characteristics (Brazeal & Couch, 2017; Cavanagh et al., 2016). By connecting FA buy-in to the five objectives and demonstrating that buy-in predicts relevant student outcomes, our prior work laid the foundation for the current study to investigate how implementation characteristics influence buy-in and utilization.

Student FA Utilization

While student behaviors likely play an important role in whether students learn from FAs, we know little about how students utilize FAs. Much of the work on student behaviors focuses on general study skills, such as the amount of time and scheduling of studying and the types of behaviors used while studying for summative exams (Gurung et al., 2010; Hartwig & Dunlosky, 2012; Holschuh, 2000; Nonis & Hudson, 2006; Richardson et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2018). The literature on deep and surface approaches to learning represents another body of research in the area of general study behaviors (Baeten et al., 2010; Struyven et al., 2005). Students using deep approaches seek to gain conceptual understanding (Davidson, 2003; Elias, 2005), whereas students using surface approaches give less effort, tend to resort to memorization, and exhibit a lack of reflection (Baeten et al., 2010). Studies have observed connections among instructors’ approaches to teaching, student perceptions, deep or surface approaches to learning, and performance (Lizzio et al., 2002; Trigwell et al., 1999, 2012), but these connections have not been examined in the FA context.

In contrast to work on general study skills, fewer studies have detailed undergraduate student behaviors while utilizing specific FAs, and no studies have comprehensively examined behaviors across a range of different FA types. Some studies in STEM have examined undergraduate student behaviors during in-class FAs, such as discussion participation, conversation domination, argument co-construction, and reasoning exchange (Eddy, Converse, & Wenderoth, 2015b; Knight et al., 2013; Koretsky et al., 2016; Kulatunga et al., 2013; Turpen & Finkelstein, 2010). For out-of-class assignments, the majority of research on student behaviors has occurred at the K-12 level. Studies of undergraduate student assignment behaviors, from across STEM and non-STEM contexts, have measured assignment completion, use of the textbook, procrastination, help-seeking behavior, contribution to group projects, and use of feedback (Aggarwal & O’Brien, 2008; Heiner et al., 2014; Hepplestone & Chikwa, 2014; Letterman, 2013; Nonis & Hudson, 2006; Orr & Foster, 2013; Sabel et al., 2017). Other studies have shown that certain FA behaviors are associated with improved course performance, such as discussing coursework with peers outside of class, preparing before class, using study guides or practice exams, and engaging with enhanced answer keys or reflection questions (Benford & Gess-Newsome, 2006; Carini et al., 2006; Gurung et al., 2010; Sabel et al., 2017).

Rationale for the Current Study

While the FA literature provides many insights on implementing FAs, several areas remain for further investigation. First, many studies have focused on one FA type, and we lack a comprehensive list of the numerous FA implementation characteristics that instructors must consider across FA types. Second, research on student learning approaches has considered general study behaviors and exam preparation or focused only on specific behaviors, and we have limited information regarding the range of behaviors students exhibit when they complete FA activities. Third, while prior literature has identified several implementation recommendations, these studies often do not incorporate student perspectives, so it remains unclear how implementation characteristics impact student engagement. Fourth, most studies have investigated an individual implementation characteristic in isolation and have not considered combined effects across implementation characteristics. Finally, many implementation recommendations emerged from outside undergraduate course settings (e.g., K-12 or non-course-based settings), and prior research has indicated that FAs can produce different outcomes across content areas such as math, science, and language arts (Kingston & Nash, 2011), so more work is needed to delineate how implementation impacts students within specific undergraduate STEM contexts. The current study in biology aimed to complement and expand the existing knowledge base by delineating and connecting different components within the FA Engagement Framework. Specifically, we aimed to describe the potential variation present within certain framework nodes and to understand how instructional features impact student FA engagement by addressing three broad research questions:

-

(1)

What general behaviors do students describe with respect to their FA utilization?

-

(2)

How do students perceive that specific implementation characteristics influence their FA buy-in and utilization?

-

(3)

What combined effects exist across different implementation characteristics?

Methods

Methodological Approach

FA implementation occurs within a complex educational environment in which student perceptions and behaviors can be affected by a host of variables, such as student characteristics, course norms, and institutional culture. Thus, we employed a qualitative approach to delineate the various dimensions underlying FA engagement and identify potential connections across framework components. We selected undergraduate biology courses that used a variety of common FA types, which enabled us to develop a more comprehensive sense of how different implementation characteristics might influence student engagement. We took a broad and inclusive perspective on what activities can be considered FAs to account for the diversity of practices used by undergraduate instructors in authentic course settings (Brazeal et al., 2016; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). By broadly characterizing connections between FA implementation and student engagement, we also sought to lay a foundation for the development of instructional resources and quantitative instruments that can apply to a variety of FA types.

Black and Wiliam’s (2009) five FA objectives relate to both the instructor and student sides of the FA Engagement Framework. For each objective, the instructor may take steps directly targeting that objective, and students take actions that determine if that objective becomes realized. However, numerous implementation characteristics affect how students engage with an FA. Thus, the five objectives represent overarching goals for the FA process, which consists of elements aligned with the objectives as well as other practical aspects of the activity. Our research design and analysis accounted for this relationship by incorporating questions and coding categories that explore the FA objectives, while also capturing the many other implementation characteristics that shape student responses.

Course Context

All eight of the focal courses were undergraduate biology courses at a large, research university. Seven of these courses occurred in spring 2015 and one occurred in fall 2015. Three courses were introductory level with enrollments of 139–249, and the other five courses ranged from sophomore to senior level with enrollments of 26–231. The instructors used various FA types as part of their normal teaching practices, meaning that the research team did not provide directions about what FAs to use or how to use them. We focused on one in-class FA and one out-of-class FA from each course. In-class FAs included clicker questions (CQ; six courses) and in-class group activities (ICA; two courses). Out-of-class FAs included online textbook-associated program (OTP) assignments (four courses), Just-in-Time Teaching (JiTT; two courses), and other types of homework completed by students outside of class (two courses). Most of the FAs occurred on a weekly basis, but instructors employing clicker questions typically used them in every class session. K.R.B. interviewed all the course instructors to provide background context. Supplementary Materials 1–3 provide details of the instructor interviews and FA implementation.

Student Interviews

We recruited students by asking them on a course survey to indicate their interest in being interviewed and emailing a subset based on random selection and available times. We analyzed a total of 38 student interviews, determining that we had reached saturation when new themes stopped emerging. Table 1 shows demographic characteristics represented by these students. Participants received a $20 gift card. K.R.B. conducted these interviews during the second half of the semester to ensure that students were familiar with the FAs. We used a semi-structured interview protocol consisting of core questions and follow up prompts. We asked each student questions pertaining to one in-class FA and one out-of-class FA, alternating the order across interviews.

The interview questions addressed different aspects of the FA Engagement Framework. Supplementary Material 4 lists the full set of interview questions. In brief, we began the interview by asking general questions about how the FA is being implemented, why they think the FA is being used, what makes them think it is being used for that purpose, and how the FA influences their learning. While studies have found mixed results about the validity of self-reported learning measures (Pike, 2011; Porter, 2013), we asked about perceived learning since it reflects student buy-in. We then asked a series of questions about how the student utilizes the FA (e.g., their level of effort and their behaviors while completing the FA). Students admitting to undesired behaviors, such as giving low effort and copying answers from the internet, gave some indication that the interview context enabled students to share without fear of retribution.

We also aimed to understand student perceptions about how implementation characteristics impact their buy-in and utilization. General questions early in the interview provided students an opportunity to identify helpful aspects, and later questions probed more specifically how they perceive particular implementation aspects to influence their learning. We asked questions related to the five FA objectives (e.g., how is learning affected by feedback methods, instructor use of the FA to change their teaching, and peer discussion structure) as well as other FA features that might influence engagement (e.g., how does the grading policy and timing of the FA affect learning). Finally, we asked how the FA could be changed to improve their learning.

Coding and Analysis

All three authors were involved in iterative thematic analysis of the transcripts (Boyatzis, 1998; Saldaña, 2015). Coding was informed by some a priori ideas from the literature, such as the five FA objectives and known implementation characteristics, and we were also able to discover and code emergent ideas. Supplementary Material 5 provides an overview of our analysis process. Given the comprehensive scope of the study and the nature of our sample, we did not parse our findings by demographic groups.

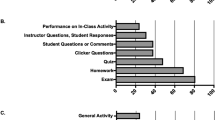

Before addressing the research questions, we developed a list of potential FA implementation characteristics. To create this list, we each separately read 4–7 student interview transcripts and noted all the implementation characteristics that students discussed (i.e., descriptive coding in which topics are identified before analyzing the effects of those topics; Saldaña, 2015). In total, we read 14 of the 38 transcripts during this stage with 1–3 interviews from each focal course. We then worked collaboratively to create a complete list of FA implementation characteristics from our notes. We continued to add to the list during later student and instructor interview analyses when we came across new characteristics. We organized our list of implementation characteristics into eight categories. To further expand and revise this list, we also solicited feedback from four instructors experienced with FAs, which led to minor modifications within the existing categories. Supplementary Material 6 provides the full list of 72 implementation characteristics, and Table 2 provides descriptions for the eight categories.

To address the three research questions, K.R.B. read through the remaining 24 interviews (three interviews per focal course) and used Dedoose software to tag excerpts (i.e., passages) with structural codes (Saldaña, 2015). The interview protocol included questions touching on student approaches, resource use, and peer discussion, and students often described their own actions when answering other questions. In these cases, the structural code “utilization” was applied to excerpts in which students discussed behaviors before, during, or after the FA (Research Question 1). When students discussed an FA implementation category, these sections were marked with structural codes corresponding to that category (Research Question 2). Each excerpt of one to several sentences could be tagged with one or multiple categories (i.e., simultaneous coding). Supplementary Material 7 provides a detailed quantification of the excerpts that emerged from this process.

This structural coding process enabled us to group related excerpts and consider responses from diverse contexts (Boyatzis, 1998; Saldaña, 2015). For each structural code, all three authors independently read the tagged excerpts and generated overarching themes. We then discussed and came to consensus on a master list of themes and repeated this process for each structural code. We also kept notes on combined effects across implementation categories and other themes that emerged, and we synthesized these notes through discussion after analyzing all the implementation categories (Research Question 3).

To address validity concerns throughout our analyses, we involved all three authors, alternated between independent and joint interactions with the data, and tasked one author with considering negative evidence for any finding. We conducted member checks with instructors to resolve unclear aspects. We triangulated our findings between instructor and student interview sources while also taking into account prior published student survey results (Brazeal et al., 2016; Brazeal & Couch, 2017). This study was classified as exempt from review for human subjects research, protocol #14314.

Findings

RQ1: What General Behaviors Do Students Describe with Respect to FA Completion?

To understand the types of behaviors that comprise the utilization node of the framework, we identified four categories of behaviors from the interviews, each including actions that may or may not support learning. Table 3 presents these utilization behaviors along with representative quotes.

Approach

The approach category encompassed behaviors related to the degree of effort students give to the FA, the amount of time students spend completing it, and their use of deep and surface approaches. Behaviors within this category that may support learning included giving high effort, working to figure out the answers, and spending enough time to adequately complete the assignment. Conversely, some students admitted that they gave lower effort, answered quickly just to finish the FA, or chose an answer randomly. Students justified these types of behaviors with reasons including that they were short on time and had other assignments (especially for out-of-class FAs), that they knew the FA was low stakes, that they were not provided enough time, or that they knew the instructor would provide the answer (especially for in-class FAs). Other reasons for giving lower effort included not knowing the answer or just not feeling like giving high effort. We also found that student-reported behaviors included both deep and surface approaches (Baeten et al., 2010). An example of a deep behavior was trying to think of the FA answer before consulting other resources or peers. Conversely, an example of a surface approach was being more concerned about just getting the right answer or getting the points, rather than learning the material.

Discussion

Students varied in whether they discussed the FA with peers. As we found in previous work, peer discussion was more prevalent with in-class than out-of-class FAs (Brazeal et al., 2016). For out-of-class FAs, some students preferred to work alone and only consulted their peers if they could not figure out the answer via other means, while a few preferred to work as part of a group. The quality of peer discussion also varied (e.g., explaining reasoning for answers versus simply exchanging the correct answer). In addition, students varied in whether they participated in whole-class discussions, most commonly used for in-class FAs (e.g., when instructors solicited student explanations for answers during an FA follow-up).

Resources

Students demonstrated a variety of ways they used resources to complete an FA, including behaviors reflecting deep and surface approaches. Before the FA, some students prepared by reading the relevant book sections or other provided materials. Other students preferred to read at other times or did not read at all. Another component of student behavior was the appropriateness of the resources they used while completing the FA. Appropriate resources were those intended by the instructor (e.g., the book, class notes, or other course materials). Many students used the Internet when completing out-of-class FAs. While some students used the Internet to learn more about the topics covered in the FA, several students used online sites as an inappropriate or unintended resource (i.e., searching for the exact questions and answers). This behavior was particularly common with respect to online textbook-associated program (OTP) assignments, since the questions and answers have typically been posted on the Internet. Students commonly use online resources when completing coursework (Hora & Oleson, 2017; Morgan et al., 2014), so it is important to understand how they view their behaviors with respect to learning. Interestingly, several students who reported that they found the exact FA prompts and answers on the internet stated that they still thought the FA was helpful to their learning because it helped them determine what to study for the exam. These students seemed to be strategically adjusting the intended purpose of the FA: instead of using it to learn initially, they were completing it quickly, and then they engaged more with the FA when studying for the exam. We also found that students consulted resources in different orders. For example, some students used the Internet to find the exact question prompt and answer as their first resource, while others tried to think of the answer themselves and then checked the book or the internet to confirm their answer.

Later Use

Finally, students varied in how they interacted with FAs after submission. These behaviors included ensuring that they can later reference the FAs (e.g., writing down in-class prompts or making notes to remind themselves to review certain topics) and using the FA and related feedback (e.g., keys, rubrics, instructor explanations) to relearn missed information as part of regular study or exam preparation. Students varied in whether they completed each of these behaviors, and some behaviors could be done in ways that may or may not have supported learning. For example, some students used FA keys to self-quiz, returned to their book or notes to improve their understanding of the topics they missed, and practiced FA prompts as part of their exam study in ways that emphasized conceptual understanding (e.g., trying to determine the depth of understanding that would be expected on exams). Despite self-testing being an effective strategy, students often use less effective methods (Karpicke et al., 2009). For example, we found that some students simply read through FA feedback with the goal of memorizing answers and, when using FAs to prepare for exams, only re-read prompts and assignments.

RQ2: How Do Students Perceive That Specific Implementation Characteristics Influence Their FA Buy-In and Utilization?

To understand connections across different framework components, we identified potential relationships between instructor implementation and student buy-in and utilization. In the following sections, we highlight how certain aspects within each implementation category can influence student engagement. The technology and mechanism of implementation category did not have enough excerpts to generate valid conclusions. Table 4 summarizes our findings for each category to aid instructors as they consider how their implementation choices may affect student engagement. For each representative quote, we indicate a student identification number (1–38).

Timing of the FA

One implementation characteristic that students perceived to have a large impact on their buy-in was the FA timing, which refers to when it is completed compared to when the material asked about in the FA is “covered” by the instructor. Both in-class and out-of-class FAs could be either pre-coverage or post-coverage. For example, clicker questions could be posed to students before or after the relevant material has been presented, and similarly out-of-class assignments could be due before or after that content was covered in class. FA timing has not received attention in reviews of best practices (Gibbs, 2010; Offerdahl et al., 2018; Shute, 2007), despite being a fundamental consideration instructors will have to make when implementing FAs.

Students held mixed opinions about pre-coverage FAs. Some students recognized benefits, such as informing the instructor of student misconceptions, promoting student accountability to prepare for class, and increased efficiency of class time. For example:

“It’s kind of challenging sometimes, because you obviously haven’t learned it yet, so it’s kind of on you, but I think it’s a good thing, because you understand the basics of it before you go into it, and then, like I said, [the instructors] add detail and kind of explain it more.” (18)

However, other students expressed concerns about pre-coverage FAs, stating that they worried they would learn the material incorrectly, that they believed this method was an inefficient way of learning, or that they preferred to be introduced to topics through lecture and then read and answer questions afterward. Resistance toward pre-coverage FAs may stem from the fact that they shift the responsibility for learning more onto the student (Akerlind & Trevitt, 1999). For example:

“You kind of have to teach yourself the topics in order to do [the pre-class assignment], which is kind of weird because it’s the professor who are supposed to, I guess, teach you. I mean you’re supposed to read the book and then understand the things but it’s easier when your professor also clarifies things. And then after he has clarified them you can go on ahead and do all the problems that they ask you. And it’s not really helpful if you have to do them by yourself when you don’t know what the topic is about.” (17)

In contrast, most students identified benefits of post-coverage FAs, including allowing students to solidify their knowledge, obtain feedback, and practice for exams.

Student buy-in regarding FA timing translated into perceived influences on their utilization behaviors in the categories of approach and resource use. Students in favor of pre-coverage FAs reported that these FAs encouraged them to read before class and improved their concentration in class. Conversely, students resistant toward pre-coverage FAs reported that this timing would lead to poorer utilization behaviors, such as giving lower effort, waiting for the instructor to explain the answer rather than trying to consider the questions (i.e., for pre-coverage in-class FAs), or looking up answers online (i.e., for pre-coverage out-of-class FAs). For example, when asked how their learning would be different if a post-class quiz were changed to a pre-class quiz, this student responded:

“I don’t know. A lot of my classes do the pre-quizzes and I kind of dread them, they’re annoying. [. . .] Usually it was, like they’re usually [online], like, timed quizzes where you just go through your stuff and you have to find the material, half the time I was just like, I would google questions and find exact answers because they’re book questions or whatever, so I didn’t feel like I actually learned very much from them, they were more of just an annoyance.” (30)

While pre-coverage timing contradicts the preferences of some students, these types of activities align with constructivist learning theory and can promote learning (Marrs & Novak, 2004). Thus, we propose that instructors will need to carefully attend to the many other implementation characteristics to optimize student engagement with these activities (several examples described below under Research Question 3).

Scheduling Logistics

Students expressed a wide variety of perceptions regarding ideal FA scheduling logistics, such as FA frequency throughout the course, number of prompts asked per class session or assignment, and amount of time allocated for completion. Despite differing opinions, we found a common theme that consistency in FA delivery is important for improving both buy-in and utilization. For example, this student expressed reduced buy-in toward irregular clicker question use:

“Sometimes we’ll have clicker questions all three days or like two days, but then we’ll go two weeks without having any. So it’s just like, I feel like they’re actually not really useful at all in this class so far.” (13)

Students also reported that spreading in-class FAs throughout the lecture was helpful to their learning while lumping them at the beginning or end of class harmed their utilization by leading to decreased effort just to finish the questions. Similarly, students expressed desire for consistency in out-of-class assignments, preferring dependable weekly schedules rather than sporadic due dates. This student explained one benefit from consistency:

“It was the fact that you, like, [the homework assignments] were consistent, like we’re getting them on a regular basis and we like kind of knew what to expect once you take them enough times.” (29)

In addition, some students cited inconsistent due dates as harmful to their utilization by leading them to forget to complete assignments.

Activity Messaging

While previous work recommends that instructors combat student resistance by explicitly discussing their rationale for using FAs (Felder, 2007; Seidel & Tanner, 2013; Silverthorn, 2006), little empirical evidence exists about how students respond to this type of instructor talk (Seidel et al., 2015). Many students reported that they did not remember whether the instructor had explained why they were using the FA, and only a few students mentioned instructor talk elsewhere in the interviews. The only other study of student perceptions of instructor messaging also found that many students did not remember that their instructor provided justification for active learning techniques (Brigati et al., 2019).

All instructors reported that they provided rationale to students about their use of in-class FAs, but a few did not for out-of-class FAs (Supplementary Material 3). Of those instructors who did discuss FA rationale, most only did so at the beginning of the course or on the syllabus. Thus, instructor talk may have influenced how students initially engaged with FAs, but students often did not recall this effect during later interviews. In cases where students remembered instructor rationale, some of these students mentioned that the instructor reiterated their reasoning multiple times throughout the semester. For example, this student described how instructors repeatedly mentioned their reasoning for using in-class group activities:

“They say all the time in class that science is a group effort, so that’s what [the instructors are] trying to reinforce in the class with the group effort.” (8)

While instructors reported rationalizing FAs to students in a variety of ways, we observed that several student mentions of instructor talk pertained to the instructor emphasizing how the FA provides valuable practice for the test. Based on these observations, we propose that revisiting rationale regularly throughout the course and framing FA rationale in terms of aspects that students may be primed to think about (e.g., exams, grades) can help student buy-in. In addition, explicit instructor talk about how students should utilize the FAs to prepare for exams could encourage good study habits and help students use FAs to take ownership of their learning.

Content

Two aspects of FA content with consequences for student engagement were the cognitive level of the prompts (Bloom et al., 1956) and the alignment of the FA with exam questions. Students used the cognitive level of the FA to gauge its role in the course. For example, some students who viewed the FA as padding grades expressed that they felt this way because it consisted of mostly lower-order prompts (e.g., knowledge, comprehension). Conversely, other students pointed to higher-order FA prompts (e.g., application, analysis) as evidence that the FA functioned to encourage critical thinking. This influence of the cognitive level of the FA on its perceived purpose translated into effects on student buy-in. Higher-order, particularly real-world application questions, were cited by students as being helpful to their learning:

“I mean, I like the JiTT questions because I feel like in most classes you go to class and you don’t understand where this applies. Like, why am I really learning this? So I like the JiTT questions in that way, where I get to see the real-world application, because I feel like most instructors are so driven by the material that we need to learn that that always gets missed in most of my classes. So I like that, because then I’m like ‘Oh’. Then when I see that connection with the outside, then I can remember it for in class.” (23)

In contrast, lower-order prompts were associated with memorization and regurgitation of information and thus were viewed as less helpful. Some students also discussed the learning benefits of challenging prompts and often equated difficulty with higher cognitive level, which has also been observed with instructors (Lemons & Lemons, 2013). In addition to cognitive aspects, students expressed a preference for FA prompts similar to exams (i.e., similar in either topic or depth) because they help students prepare for the exam, while FAs unrelated to exam questions were seen as unhelpful or a waste of time.

Students indicated that the cognitive level and alignment of the FA influenced their behaviors within all four utilization categories. Higher-order prompts and high alignment with the exam encouraged students to give more effort, read before coming to class, discuss with peers, return to the FA to review questions, and use the FA to study for the exam. For example, this student explained how lack of alignment with the exam influenced utilization:

“I think that it does need to be more reflective of the exam, because that’s what we like, we like to be primed for the exam, like, ‘Oh, this is just like a [OTP] question. Oh, this is just like a recitation question.’ So it’s just like more motivation for us, but because we feel like—and I know there’s a lot of students who feel like this—because we feel like the [OTP] questions are not applicable to the exam or the recitation material, we feel like, ‘Well, what’s the point of us doing that before class?’ And I think that leads the students [to] not reading early, not focusing on the [OTP assignments].” (12)

Overall, students valued and engaged more deeply with FA prompts they perceived to be higher-order, particularly real-world application, as well as prompts aligned with exam questions. Interestingly, these results diverge from prior studies suggesting that FA approaches may be more effective for familiar or less complex tasks (Kingston & Nash, 2011).

Feedback

The way that feedback was provided to students varied widely among the FAs studied, but there were a few broadly applicable conclusions about how students perceived feedback. Given that feedback has been studied extensively (e.g., Shute, 2007), we focus our attention on the aspects that students view as most salient to their buy-in and utilization. While students acknowledged that they received feedback in discussion with their peers and through self-assessment, they expressed that they also wanted to receive a definitive correct answer along with an explanation for why that answer was correct and others were incorrect (e.g., from the instructor or a key):

“Probably the part [of the clicker questions] where like we do go over the, like why things are right and wrong is especially helpful.” (33)

Students also expressed a desire for the instructor to provide in-depth explanations for FA questions that many students missed. Some felt an FA was not helpful to their learning unless the instructor directly provided feedback:

“If [the online homework] were discussed in class like the day after, they would be better, because there’s no point in doing an assignment if you’re not going to get feedback on what you did wrong or what the right answer was, and there really isn’t any of that. It’s just an online assignment, so you go do it and then we just continue with lecture like nothing happened.” (27)

Thus, an explanation from the instructor can help students see the benefit of an FA. The accessibility of FA prompts and answers after the FA was completed also affected buy-in, with some students expressing frustration when they did not have easy access to FA feedback outside of class.

The amount and accessibility of FA feedback also influenced utilization behaviors, particularly later use of the FA. For example, some students reported that when the instructor spent class time explaining commonly missed FA questions, this encouraged them to make a note to review those topics later, which they might not have thought to review otherwise. In addition, students’ ability to access FA feedback influenced whether they used the FA when studying for the exam. Students expressed preferences for the instructor posting the FA prompts and answers on the course website. When the only access to FA feedback was to record the answers themselves, students often reported not doing so.

Facilitating Peer Learning

While student discussion of course material both during and outside of class has been linked with measures of learning and performance (Benford & Gess-Newsome, 2006; Carini et al., 2006; Hubbard & Couch, 2018; Smith et al., 2009), and peer discussion is one of the five FA objectives (Black & Wiliam, 2009), less is known about how students value and engage in peer discussion of FAs. We found differences between in-class and out-of-class FAs; therefore, we present separate conclusions for these FA types.

For in-class FAs, many students generally viewed some degree of peer discussion as helpful for their learning, and some students that preferred less social interaction recognized the benefits of discussion even though it was outside their comfort zone. This student explained some of the benefits:

“I guess in group activities I like if someone understands something more than the other person, it gives you the opportunity to teach them, and I think once you understand a topic and you’re able to teach it to someone else that like proves that you’ve mastered that skill or that topic, which helps you study more and then also like helps the other student learn from–maybe like they didn’t understand it from [the professor] and one of our group members was able to explain it in like a better way for students to understand.” (4)

Students reported several ways in which instructors facilitated discussion of in-class FAs. The most common way was through verbal encouragement, sometimes with specific instructions (e.g., asking students to discuss with someone who answered differently, telling students to share their thinking). Indeed, well-structured instructor cues have been shown to improve the quality of student discussions (Knight et al., 2013). In addition to verbal cues, students reported other instructor behaviors that helped them engage in productive discussions. These instructional behaviors included giving time for individual thinking before discussion, not allowing students to blurt out answers before everyone has had a chance to think, and preventing discussion time from going too long. Circulation of instructors and learning assistants during discussion helped students stay on task and prompted discussion in groups where it had stalled:

"If you were just kind of sitting there, she’ll make sure to–she doesn’t really call you out, but she’ll come around and make sure like, 'Hey, are you guys talking together, or what do you guys think?’ And then she’ll just make sure everyone’s really engaged, so that’s kind of nice." (22)

Students also appreciated circulation because it allowed them to get help if they were confused and ask questions they might have felt uncomfortable asking in front of the whole class.

The use of formal student groups as a strategy for encouraging discussion yielded mixed opinions from students. Buy-in toward formal groups often depended on whether all group members engaged, and students commonly complained about their group members not participating. This social loafing has also been previously noted as a predictor of negative attitudes toward group projects (Aggarwal & O’Brien, 2008; Pfaff & Huddleston, 2003).

Student buy-in regarding groups also depended on whether they were self-selected or instructor-assigned. While some students approved of assigned groups, others preferred self-selected groups because they felt more comfortable during discussion and valued group members who placed similar importance on the course:

“When it’s like a huge lecture hall, I’m not a big fan of the group work, especially when I get put in a group with people that I don’t really know, especially when we’re not getting along that well. It’s really easy when you’re put with people you can talk to continually and you know care about the class, I guess. Like I don’t want to generalize people, but some people care more than others. And so, and like smaller classes where I know more people in it and I have my friends in it, it’s really easy to talk through the topics and converse about those things.” (31)

These findings contribute insights into why self-selected groups yield higher student satisfaction compared with random group assignment (Chapman et al., 2006; Myers, 2012). Strategic group assignment based on GPA and interest may improve satisfaction (Brickell et al., 1994), but studies find mixed results as to whether instructor-assigned or self-selected groups have better learning outcomes (Brickell et al., 1994; Hilton & Phillips, 2010; Swanson et al., 1998; van der Laan Smith & Spindle, 2007).

We found that instructor facilitation and student engagement in peer discussion was less common for out-of-class FAs. Common reasons given by students for not discussing out-of-class FAs included preferring to complete assignments alone or not knowing anyone else in the class. Some students who did report discussing outside of class expressed that they did so because the FA was challenging and the answers could not readily be found on the Internet. These findings provide valuable new insights, as little prior work exists on student discussion of out-of-class FAs in undergraduate courses. Future work could test whether instructor interventions such as repeated and specific verbal reminders to discuss, improvements to FA content, use of online discussion boards, and establishment of formal discussion groups during class to help students find potential discussion partners. Alternatively, discussion may be better supported by setting aside time during class for students to discuss out-of-class assignments, as was the case for the two instructors who used JiTT.

Grading Policy

Student perceptions about the fairness of grading policies influence their attitudes, motivation, and resistance (Chory-Assad, 2002; Chory-Assad & Paulsel, 2004). Our first main finding regarding grading policy pertained to the inclusion of the FA in the course grade. All of the FAs in this study were graded in some form, so we cannot draw conclusions about ungraded FAs. However, students acknowledged that grading the FA helped keep them accountable for completing it, compared to if it were optional. In terms of utilization behaviors, grading the FA encouraged attendance or completion and fostered higher effort toward the FA.

The second main theme concerned how the FAs were graded. Students discussed the pros and cons of participation-based versus correctness-based grading schemes. Students appreciated the freedom from being penalized while they were still learning material, which fostered critical thinking and peer discussions focused on understanding rather than just the correct answer. Some expressed the downside that participation grading might also cause them to not perceive an activity as valuable and therefore give less effort. Students with positive opinions of correctness grading said it encouraged increased effort, preparation before class, and peer discussion. Conversely, other students cited concerns that correctness grading created stress and pressure (particularly for in-class FAs) or prompted them to engage in behaviors that undermined learning, such as searching the internet to find the exact questions and answers (particularly for out-of-class FAs). These connections between FA grading and student behaviors were described by a student reflecting on how they would respond if an in-class activity was changed to correctness grading:

“It’d be probably a lot more stressful trying to make sure I get the right answer and I don’t know if I’d be trying to learn as much if I was just trying to get the right answer or not actually, uh, concern myself with learning what the question’s about. I’d probably be just like asking a neighbor or something what the right answer [is], just so I get the points.” (2)

Our findings provide further support that correctness-based grading can lead to an emphasis on the correct answer over sense-making (Turpen & Finkelstein, 2010) and less collaborative discussions (James, 2006; James et al., 2008), while also showing that some students value other benefits of correctness grading.

While some sources recommend participation grading for FAs (Angelo & Cross, 1993), given the balance of pros and cons of participation versus correctness grading, hybrid grading schemes may offer a reasonable compromise. These policies require correctness to achieve full credit, which can foster accountability, but also include built-in factors that allow for leniency to reduce stress as students learn (e.g., offering partial credit for incorrect answers, providing multiple tries to answer, or dropping some of each student’s lowest FA grades). Providing adequate leniency may be necessary to discourage the negative outcomes associated with higher stakes, correctness grading policies (James et al., 2008).

RQ3: What Combined Effects Exist Across Different Implementation Characteristics?

While previous studies have often focused on specific FAs in particular contexts, considering several FAs together enables us to identify and describe relationships between implementation characteristics as well as other themes that emerged in more than one implementation category. These cross-cutting themes provide additional depth in understanding how implementation characteristics affect other framework components.

Implementation Characteristics Have Combined Effects on Student Engagement

FA timing affected several other implementation aspects. For example, whether the FA was completed before or after the material was covered in the course impacted student perceptions about the fairness of the grading policy. Students often expressed that a correctness-based grading scheme was unfair for pre-coverage FAs:

“I think some of the [JiTT] questions are way too hard, and I don’t think it’s fair, as far as grading goes, to actually grade that, because we don’t know anything about it. Obviously, we’re supposed to be reading and learning about it beforehand, but I think it should be more of like a participation grade again, if it’s stuff we haven’t even covered.” (38)

Conversely, students were more open toward correctness-based grading for post-coverage FAs. Thus, instructors should consider more lenient grading policies for pre-coverage FAs to help reduce resistance.

Similarly, FA timing shaped student perceptions about the cognitive level of the FA content. While students appreciated higher-order FA prompts aligned with the exam, some students complained that pre-coverage FAs were too difficult to attempt before the content was covered in class. Unfortunately, this creates a dilemma for instructors considering what type of content to include on pre-coverage FAs. It makes sense to give students lower-level prompts as part of the pre-class assignments to prepare them before class; however, this may be at odds with student preferences for having FAs similar to exams, which may be higher order. Therefore, instructors may need to prioritize the goals they have for the particular FA, while explaining their rationale to students and providing opportunities through other FAs for students to practice higher-order thinking.

FA timing also impacted feedback. We found that student perceptions about the importance of the instructor spending time in class on frequently missed questions were particularly beneficial for pre-coverage FAs. These results suggest that instructor use of FAs to alter their teaching and give feedback will help alleviate student concerns about learning material incorrectly on pre-class FAs.

We also found that perceptions of peer discussion depended on other implementation categories. Some students expressed higher buy-in toward peer discussion if they viewed FA content to be challenging and aligned with exams. In addition, students were more open toward peer discussion in class if they knew they would be getting feedback from the instructor after the discussion session. Thus, improved content and feedback can encourage buy-in toward and utilization of peer discussion.

The FA literature contains little investigation about how different FA implementation characteristics have combined effects. The examples provided here support the idea that instructors should consider how students will perceive the FA as a whole—with particular attention to FA timing—rather than only considering each characteristic in isolation. While certain effects may have been less salient in student interviews, the number and range of excerpts reflecting combined effects lends strong support to the complexity of factors affecting student experiences.

Some Students Embrace a Degree of “Acceptable Discomfort” When FA Implementation Contradicts Their Learning Preferences

While students often expressed learning preferences, some described how they could tolerate certain approaches that contradicted their instincts if they saw the benefit behind a different way of learning. For example, some students expressed a preference for learning alone rather than learning with peers, such as during clicker questions:

“I’m more of an independent person, I guess. I would rather just work through things on my own.” (1)

However, despite preferring to work alone, a few students expressed that they could see and accept some benefit to peer discussion:

“I don’t really like working in groups, but I do think they help. It’s weird. I’d rather do things. If it comes to like a project or something, I’d rather just do it myself. I’d rather get it over with, but if it comes to like going over a question or going over something, then it makes it helpful to hear somebody else’s insight.” (37)

Thus, we found that some students could see the usefulness of learning strategies outside of their comfort zone.

Another example of acceptable discomfort related to preferences regarding FA timing. Some students expressed resistance toward pre-coverage FAs because this timing contradicted their preferred order of learning tasks. However, some of these students also expressed openness to a contradiction of their learning preference. This student explained their dislike for pre-coverage FAs:

“It forces me to actually like learn stuff before I come to class. I mean that sounds really bad but if I come into class I’d like to start off with a clean mind in the morning and not having to like relearn stuff. Like I kind of want to put it off to the end but that’s not feasible in this class.” (19)

However, after a follow-up question about how the FA should be implemented with respect to timing, this student responded:

“Probably the way that they’re doing it now. I mean, although I don’t like it, I mean, it [. . .] helps cushion what we already know. It helps build up to that so you can move on to the next [OTP] assignment and then kind of build to the bigger picture again.”

Creating “acceptable discomfort” for students to step outside of a preferred learning habit will likely need explicit guidance. We suggest that instructors use a combination of design elements and targeted messaging to help students buy-in to FA methods that contradict their learning preferences. Important design elements may make it easier for students to become more comfortable with new ways of learning. For example, creating FA prompts that are challenging, higher-order, and aligned with exam questions as well as giving students the opportunity for individual thinking time prior to discussion may help students realize the value of engaging in peer discussions. Similarly, to help ameliorate discomfort with pre-coverage FAs, instructors can provide feedback after these activities (e.g., providing explanations for commonly missed questions). Additionally, instructors can highlight the rationale behind certain implementation characteristics throughout the course. For example, instructors can explain why discussing with peers is helpful or point out after an exam how specific FA questions were aligned to exam questions. Similarly, during a class session in which students tackle a particularly difficult topic, instructors can emphasize that students could take on this particular problem because they had previewed certain information before class.

Conclusions

Drawing on Black and Wiliam’s (Black & Wiliam, 2009) five FA objectives and guided by the FA Engagement Framework, this study sought to elaborate how students within one STEM discipline perceived FA implementation to influence their buy-in, utilization, and learning. We began by delineating the many implementation characteristics involved with commonly used FAs. Outlining these aspects will enable future work to test their importance and continue identifying best practices, especially for out-of-class FAs for which few guidelines exist at the undergraduate level. We also described a range of general behaviors students employ when utilizing these FAs. While previous studies included some of these behaviors with respect to specific FAs, the current study includes a more comprehensive and generalized outline of potential student behaviors across many FA types. We have provided a more nuanced understanding of how students can employ a mixture of utilization behaviors, including those that may or may not support learning. Future work can also take a more directed approach to characterize specific aspects of utilization behaviors (e.g., dissecting answering strategies or Internet use) and compare how students modulate their behaviors under different implementation conditions. This work will also help instructors understand how students use FAs and lead discussions with students about how to best use FAs to maximize their learning (e.g., by prompting students with metacognitive exercises; Tanner, 2012).

Next, we provided nuanced insights into how specific implementation characteristics influence student perceptions and behaviors and outlined ways that instructors might promote engagement. We found that for some of the implementation categories, students value practices aligned with recommendations in the literature, lending further credence to these practices and deepening our understanding of why they foster student engagement and learning. For example, we found that student buy-in and utilization can be improved by using higher-order prompts aligned with exam questions (Gibbs, 2010; Offerdahl et al., 2018), providing feedback containing explanations (Shute, 2007), and using specific strategies to promote student discussion (Fagen et al., 2002; Tanner, 2009). Conversely for other implementation categories, little empirical work existed, particularly within undergraduate STEM disciplines, and we found that student views did not align with certain recommendations. For example, FA timing has received little prior attention, and while pre-class timing is recommended as a way to improve student learning (Marrs & Novak, 2004), we found that many students reported resistance and poor utilization in response to this timing. Thus, while students can see value in any of the FA types, instructors will likely need to make concerted efforts to improve student engagement with pre-class FAs. As another example, despite little empirical evidence, teaching guides and workshops often emphasize the importance of instructor messaging to improve buy-in. However, we did not find strong evidence in support of this claim, either because messaging is not a highly effective method, because instructors provided messaging that was unconvincing, or because students do not recall early messaging as salient to their perceptions. Furthermore, few studies have examined how students react to different grading schemes, and while other work recommends participation grading (Angelo & Cross, 1993), we found that this may not be sufficient to promote positive engagement for some students.

This study examined broader themes across different implementation categories, which highlights the trade-offs instructors must consider. Understanding the complex interplay among task characteristics and instructional contexts represents an important gap in the FA literature (Shute, 2007). Importantly, the inclusion of a range of FA types in our sample enabled us to explore combined effects of different activity characteristics. For example, students appear to react differently to grading schemes, prompt cognitive levels, and feedback methods for pre-class FAs versus post-class FAs. These results underscore that studies focusing on only one FA characteristic should not assume that their findings apply across FA types, which have different activity characteristics. Furthermore, this study improves understanding of student resistance, a topic of much concern for STEM instructors but that has received little attention in STEM education studies (Seidel & Tanner, 2013; Tharayil et al., 2018). We described specific reasons why students may resist particular activities, thereby giving instructors ways that they can help students optimize their interactions with FAs and find a level of “acceptable discomfort” with practices they initially resist. Moreover, the finding that students can tolerate some level of discomfort challenges the notion that student resistance toward certain instructional practices is inflexible.

Altogether, our work lends credence and detail to the model expressed by Prosser and Trigwell (2014) that variation in instructional approaches impacts student perceptions and behaviors. Furthermore, our study demonstrates how the interplay between instructor and student actions can ultimately shape whether an FA produces learning opportunities aligned with the five FA objectives (Black & Wiliam, 2009). While our study focused on biology courses, we suspect that many of our findings would also apply across other STEM courses, but more work is needed to explore potential differences based on disciplinary norms and content. Table 5 provides a road-map for instructors to reflect on their own activities. In the longer term, our efforts to elaborate different dimensions of the FA Engagement Framework will provide a basis for the development of resources and instruments to further examine the complex connections between activity characteristics, FA engagement, and student learning on a broad scale.

References

Aggarwal, P., & O’Brien, C. L. (2008). Social loafing on group projects: Structural antecedents and effect on student satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Education, 30(3), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475308322283.

Akerlind, G. S., & Trevitt, A. C. (1999). Enhancing self-directed learning through educational technology: When students resist the change. Innovations in Education and Training International, 36(2), 96–105.

Andrews, T. M., Leonard, M. J., Colgrove, C. A., & Kalinowski, S. T. (2011). Active learning not associated with student learning in a random sample of college biology courses. CBE Life Sciences Education, 10(4), 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.11-07-0061.

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Baeten, M., Kyndt, E., Struyven, K., & Dochy, F. (2010). Using student-centred learning environments to stimulate deep approaches to learning: Factors encouraging or discouraging their effectiveness. Educational Research Review, 5(3), 243–260.

Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Kulik, C.-L. C., Kulik, J. A., & Morgan, M. (1991). The instructional effect of feedback in test-like events. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 213–238.

Benford, R., & Gess-Newsome, J. (2006). Factors affecting student academic success in gateway courses at Northern Arizona University. Center for Science Teaching and Learning, Northern Arizona University, ERIC Document No ED495693

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in education, 5(1), 7–74.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability (formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education), 21(1), 5–31.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, F. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals, Handbook I: Cognitive domain. David McKay Co..

Boekaerts, M., & Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology, 54(2), 199–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications, Inc..

Brazeal, K. R., & Couch, B. A. (2017). Student buy-in toward formative assessments: The influence of student factors and importance for course success. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v18i1.1235.

Brazeal, K. R., Brown, T. L., & Couch, B. A. (2016). Characterizing student perceptions of and buy-in toward common formative assessment techniques. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(4), ar73. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0133.

Brickell, L. C. J. L., Porter, L. C. D. B., Reynolds, L. C. M. F., & Cosgrove, C. R. D. (1994). Assigning students to groups for engineering design projects: A comparison of five methods. Journal of Engineering Education, 83(3), 259–262.

Brigati, J., England, B. J., & Schussler, E. (2019). It’s not just for points: Teacher justifications and student perceptions about active learning. Journal of College Science Teaching, 48(3), 45–55.

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9.

Cavanagh, A. J., Aragón, O. R., Chen, X., Couch, B., Durham, M., Bobrownicki, A., et al. (2016). Student buy-in to active learning in a college science course. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(4), ar76. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-07-0212.

Chapman, K. J., Meuter, M., Toy, D., & Wright, L. (2006). Can’t we pick our own groups? The influence of group selection method on group dynamics and outcomes. Journal of Management Education, 30(4), 557–569.

Chappuis, S., & Stiggins, R. J. (2002). Classroom assessment for learning. Educational Leadership, 60(1), 40–44.

Chory-Assad, R. M. (2002). Classroom justice: Perceptions of fairness as a predictor of student motivation, learning, and aggression. Communication Quarterly, 50(1), 58–77.

Chory-Assad, R. M., & Paulsel, M. L. (2004). Classroom justice: Student aggression and resistance as reactions to perceived unfairness. Communication Education, 53(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/0363452042000265189.

Davidson, R. A. (2003). Relationship of study approach and exam performance. Journal of Accounting Education, 20(1), 29–44.

Dunn, K. E., & Mulvenon, S. W. (2009). A critical review of research on formative assessment: The limited scientific evidence of the impact of formative assessment in education. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14(7), 1–11.

Eddy, S. L., Brownell, S. E., Thummaphan, P., Lan, M.-C., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2015a). Caution, student experience may vary: Social identities impact a student’s experience in peer discussions. CBE Life Sciences Education, 14(4), ar45. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-05-0108.

Eddy, S. L., Converse, M., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2015b). PORTAAL: A classroom observation tool assessing evidence-based teaching practices for active learning in large science, technology, engineering, and mathematics classes. CBE Life Sciences Education, 14(2), ar23. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-06-0095.

Elias, R. Z. (2005). Students’ approaches to study in introductory accounting courses. Journal of Education for Business, 80(4), 194–199.

Ernst, H., & Colthorpe, K. (2007). The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Advances in Physiology Education, 31(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00107.2006.

Fagen, A. P., Crouch, C. H., & Mazur, E. (2002). Peer instruction: Results from a range of classrooms. The Physics Teacher, 40(4), 206–209.

Felder, R. M. (2007). Sermons for grumpy campers. Chemical Engineering Education, 41(3), 183.

Freasier, B., Collins, G., & Newitt, P. (2003). A web-based interactive homework quiz and tutorial package to motivate undergraduate chemistry students and improve learning. Journal of Chemical Education, 80(11), 1344.

Freeman, S., O’Connor, E., Parks, J. W., Cunningham, M., Hurley, D., Haak, D., et al. (2007). Prescribed active learning increases performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sciences Education, 6(2), 132–139.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415.

Gibbs, G. (2010). Using assessment to support student learning. Leeds Met Press.

Gurung, R. A., Weidert, J., & Jeske, A. (2010). Focusing on how students study. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 28–35.

Hacker, D. J., Dunlosky, J., & Graesser, A. C. (1998). Metacognition in educational theory and practice. Mahwah, N.J: Routledge

Hartwig, M. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2012). Study strategies of college students: Are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(1), 126–134.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487.

Heiner, C. E., Banet, A. I., & Wieman, C. (2014). Preparing students for class: How to get 80% of students reading the textbook before class. American Journal of Physics, 82(10), 989–996.

Hepplestone, S., & Chikwa, G. (2014). Understanding how students process and use feedback to support their learning. Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 8(1), 41–53.

Hilton, S., & Phillips, F. (2010). Instructor-assigned and student-selected groups: A view from inside. Issues in Accounting Education, 25(1), 15–33.

Holschuh, J. P. (2000). Do as I say, not as I do: High, average, and low-performing students’ strategy use in biology. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 31(1), 94–108.

Hora, M. T., & Oleson, A. K. (2017). Examining study habits in undergraduate STEM courses from a situative perspective. International Journal of STEM Education, 1(4), 1–19.

Hubbard, J. K., & Couch, B. A. (2018). The positive effect of in-class clicker questions on later exams depends on initial student performance level but not question format. Computers & Education, 120, 1–12.

James, M. C. (2006). The effect of grading incentive on student discourse in peer instruction. American Journal of Physics, 74(8), 689–691.

James, M. C., Barbieri, F., & Garcia, P. (2008). What are they talking about? Lessons learned from a study of peer instruction. Astronomy Education Review, 7(1), 37–43.

Jensen, J. L., Kummer, T. A., & Godoy, P. D. D. M. (2015). Improvements from a flipped classroom may simply be the fruits of active learning. CBE Life Sciences Education, 14(1), ar5. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-08-0129.

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger III, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17(4), 471–479.

Kingston, N., & Nash, B. (2011). Formative assessment: A meta-analysis and a call for research. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(4), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2011.00220.x.

Kluger, A., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 254–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254.

Knight, J. K., & Brame, C. J. (2018). Peer Instruction. CBE Life Sciences Education, 17(2), fe5. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-02-0025.

Knight, J. K., Wise, S. B., & Southard, K. M. (2013). Understanding clicker discussions: Student reasoning and the impact of instructional cues. CBE Life Sciences Education, 12(4), 645–654.

Koretsky, M. D., Brooks, B. J., White, R. M., & Bowen, A. S. (2016). Querying the questions: Student responses and reasoning in an active learning class. Journal of Engineering Education, 105(2), 219–244.

Kulatunga, U., Moog, R. S., & Lewis, J. E. (2013). Argumentation and participation patterns in general chemistry peer-led sessions. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50(10), 1207–1231.

Lake, D. A. (2001). Student performance and perceptions of a lecture-based course compared with the same course utilizing group discussion. Physical Therapy, 81(3), 896–902.

Lemons, P. P., & Lemons, J. D. (2013). Questions for assessing higher-order cognitive skills: It’s not just Bloom’s. CBE Life Sciences Education, 12(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0024.

Letterman, D. (2013). Students perception of homework assignments and what influences their ideas. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 10(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v10i2.7751.