Abstract

Scores of intervention programs these days apply instructional and, sometimes, systemic strategies to reduce bullying in schools. However, meta-analyses show that, on average, such programs decrease bullying and victimization only by around 20%, and often show no or negative effects in middle and high schools. Due to these sobering results, we propose the idea that bullying prevention for adolescents needs to focus more strongly on systemically informed relationship-building efforts. Building on past research, this study focuses on several aspects of relationships and classroom climate which are significant predictors of bullying behaviors: SES, ethnicity, and teaching quality. We propose the hypothesis that the link between classroom-level bullying and three classroom-level factors—students’ SES background, students’ ethnicity, and teaching quality—is mediated by the quality of student-teacher and student-student relationships (STR and SSR). The study uses multilevel structural regression modeling (M-SRM) to analyze a large and ethnically diverse American survey dataset (N = 146,044 students). Results confirm the hypothesis, showing that the relationships between SES and bullying, and between ethnicity and bullying, are entirely mediated by the quality of STR and SSR; the link between SES and bullying is even over-explained by the two relationship factors. Furthermore, the quality of STR is a positive predictor of medium strength (standardized coefficient = 0.45) of the quality of SSR. The findings suggest that schools with high levels of bullying behavior among students need to (re-)focus teacher professional development on relationship-building skills as well as instructional and a range of systemically informed improvement efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

There is a growing appreciation that bullying, and bully-victim-bystander behavior, is a prevalent and profoundly toxic experience for K-12 students, to a greater or lesser extent around the world (Cohen and Espelage 2020). Research shows that bullying behavior in schools is widespread (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2017a) and negatively affects not only those directly involved, i.e., victims and bullies (Gini and Pozzoli 2009), but also the witnesses who see and/or hear about mean and cruel behavior (Polanin et al. 2012; Twemlow and Sacco 2011). Consequences of high-level school bullying climates include physical and emotional pain (Bogart et al. 2014; Hyman 2006), sleeplessness (Hunter et al. 2014; Sanchez et al. 2001; van Geel et al. 2015), psychosomatic disturbances (Gini and Pozzoli 2013), depression and other severe psychiatric disorders (Arseneault et al. 2008; Fisher 2012; Holt et al. 2015; Schreier et al. 2009), obesity (Baldwin et al. 2015), truancy (Reijntjes et al. 2011; Gastic 2008), delinquency (Theriot 2004), and lower academic achievement (Ponzo 2013).

The extraordinary and growing interest in bullying has been both importantly helpful as well as problematic. Historically, most educational systems around the world were focused on physical forms of danger and cruel behavior. It is only in very recent decades—and for many countries, only a handful of years—that we have begun to recognize, focus on, and seek to prevent social-emotional forms of mean, cruel, and disrespectful behaviors (Cohen and Espelage 2020). There is not a consensus about how to define bullying. Many countries use the three-part, scholarly definition of bullying (Olweus 1993): (1) a person or group who has more power, (2) intentionally acts in hurtful, mean, and/or disrespectful ways, (3) repeatedly. This definition is problematic in three important ways. First, many educators “on the ground” are sometimes confused about whether one person or group has more power than another. Second, it is sometimes very difficult to know whether an act was intentional or not. This scholarly definition is also problematic for another important reason: Mean, bullying behaviors are not solely about a person or group of people acting in mean, cruel, and/or disrespectful ways to another. They are also a social process. As Slaby et al. (1994) and Twemlow et al. (2001) suggested many years ago, there is virtually always a witness—such as bystanders who passively or actively support mean, bullying behaviors or “upstanders” who struggle—in the best sense of the word—to consider how to be helpful to the target. In other words, this scholarly definition is focused on the individual or group who is perpetuating mean, cruel, and/or disrespectful acts and negates the social nature of bullying behaviors.

Mean, cruel, and/or disrespectful behaviors are—by definition—relational: One person or group is acting in particular hurtful ways to another. In addition to students bullying other students, it has been found that teachers bully students, students bully teachers (Twemlow et al. 2006; Pervin and Turner 1998), and teachers can suffer in bullying climates as much as students do (Bernotaite and Malinauskiene 2017). Again, there are virtually always witnesses who see or hear about these behaviors (Atlas and Pepler 1998; Craig and Pepler 1997; Craig et al. 2000; Smokowski and Evans 2019).

Taking on a relational or triadic perspective, this study’s purpose is to make a contribution to scientific literature that explores why high-level bullying climates in schools occur in the first place in order to generate recommendations for preventing them.

Specifically, this study draws from Bourdieu’s (1990) habitus theory, among others, and tests the hypothesis that poor relationship climates—in terms of student-teacher and student-student relationships—are a root cause of higher levels of bullying behavior in classrooms with more disadvantaged students and poorer teaching quality.

The focus of this study is on older students in secondary schools. There are now scores of bully prevention programs that include a wide range of instructional (e.g., student and/or parent learning/training) and sometimes, systemic goals and improvement strategies (AERA 2013; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016; Vreeman and Carroll 2007). But, meta-analytic studies have shown that, on average, these programs decrease bullying and victimization by around 20–30%, with similar reductions for cyberbullying (Gaffney et al. 2019; Ttofi and Farrington 2011). Another meta-analytic study has shown differential findings for primary vs high school bully prevention efforts: Programs in elementary schools tend to be quite effective, but in middle and high schools, these efforts are just as likely to make bullying worse (Yeager et al. 2015). In other words, we are far from being able to eliminate bullying behavior in schools, and there is a particular need for studying bullying among adolescents.

The Link Between Disadvantaged Family Background and Bullying Behavior

Levels of bullying behavior differ not only between individuals but also between contexts, such as classrooms (Williford and Zinn 2018) and schools (Payne and Gottfredson 2004). One explanation for this might simply be that students from different family backgrounds tend to behave differently. Schools with larger numbers of students whose families are socioeconomically worse-off have been found to have, on average, more bullying than schools whose students predominantly come from higher-socioeconomic status (SES) households (Due et al. 2009; Tippett and Wolke 2014).

Several theories try to explain why. For example, there is an ongoing research debate on whether higher levels of violence in the American South compared with the American North—which concur with regional bullying trends that find more bullying in schools in the American South than schools in the American North (McCann 2018)—are due to cultural differences, or due to poverty and socioeconomic inequality (Lee et al. 2007). However, these theories are not mutually exclusive and consistent with the fact that lower SES neighborhoods tend to have higher crime rates (Imran et al. 2018) and that lower SES adolescents more strongly self-report aggression—and bullying-related mindsets, such as lower feelings of a sense of purpose and academic status insecurity (Dietrich and Zimmermann 2019).

Quantitative studies also reveal that ethnicFootnote 1 background is a significant predictor of bullying (Nguy 2004; Psalti 2007; Scherr et al. 2010; Wright and Wachs 2019). This link might be partially explained by the fact that many ethnic minority groups—such as Blacks and Latinos in the USA (Shapiro 2017) and many immigrant groups in Europe (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2017b)—are socioeconomically worse-off than members of their countries’ ethnic majority populations. In other words, students from ethnic minority groups may be more involved in bullying because they have—on average—lower SES family backgrounds than their ethnic majority peers, and lower family SES has been found to predict more bullying involvement (Dietrich and Zimmermann 2019; Tippett and Wolke 2014).

However, research also shows that ethnic family background remains a significant predictor of bullying when family SES is controlled for (Tippett and Wolke 2014). This indicates that other ethnicity-related factors impact higher levels of bullying behavior among students of color. It has been found that there is more social status insecurity among lower SES students (Dietrich and Ferguson 2019; Wright and Wachs 2019), possibly induced by social stigma about poor people. These feelings of insecurity partially mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and bullying (Dietrich and Ferguson 2019). Similarly, differences in bullying behavior between White students and students of color might be due to differences in social status insecurity.

The concept of pluralistic ignorance (Perkins 2003) might also help explain ethnic differences in bullying behavior. Students of color may have misperceptions about their peers’ expectations and might wrongly believe that the majority of their peer groups’ members condone aggression or even expect them to be aggressive. Indeed, negative stereotypes about minority groups are so pervasive that they are often held—consciously or unconsciously—by members of the negatively stigmatized groups themselves (Uzogara et al. 2014; Erikson 1994).

In line with this idea is a research from Ferguson (2016), who found in a large sample of 2700 US classrooms that students of color themselves report more misbehavior and disrespect towards their teachers than White students, but also more pressure from peers to do things they do not want to do. This suggests that worse behavior among students of color is a symptom of worse relationship dynamics, which are ultimately caused by negative stereotypes about people of color. If this is correct, it might be that there are smaller differences in bullying behavior between White students and students of color in classrooms and schools with better relationship dynamics, where all students experience less pressure from their peers.

Family Status, Teaching Quality, and Bullying

Another explanation for the link between students’ family background characteristics and their bullying behavior might be that lower SES and ethnic minority students tend to go to schools that evidence lower levels of teaching quality (Nieto and Ramos 2015). Research shows a significant relationship between teaching styles/teaching quality and students’ bullying (Dietrich and Hofman 2019; Roth 2011). Roth (2011) explored whether the relationship between the quality of teaching—with respect to support for student autonomy and recognition of student perspectives—and bullying behavior is mediated by students’ internalization of positive values. The results support the idea that more autonomy-supportive teaching (AST) instills pro-social values in students, leading to reduced bullying behavior. Similarly, Wang et al. (2015) found that attitudes towards bullying mediates the relationship between positive student-teacher relationships and less bullying. Hence, if schools in lower SES neighborhoods are less likely to provide teaching methods with strong relationship-building components than schools in middle- and upper-class neighborhoods (Sass et al. 2010), lower SES students—including a disproportionately large number of students from ethnic minority backgrounds—are less likely to internalize pro-social values and anti-bullying attitudes and, in turn, more likely to bully or condone bullying as a bystander.

Another explanation for the link between teaching and bullying is that classroom management skills are an integral part of teaching, and, by definition, these skills reduce all forms of misbehavior among students (Hardin 2008). Indeed, empirical results show significant negative links between teachers’ classroom management skills and their students’ bullying behavior (Allen 2010). But how exactly can teachers improve their classroom management skills? One approach might be by advancing and professionalizing their relationship-building skills (Campbell 2018).

Bullying and Relationship Climates

Empirical results show a significant link between the quality of relationships in schools and all sorts of negative student behaviors. For example, drawing from Baumrind’s (1966) parenting styles framework, in a series of studies, Cornell and his colleagues have shown that “authoritative school climates” predict better student behavior, including less bullying, fighting, alcohol and marijuana abuse, carrying of weapons, gang membership, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Cornell and Huang 2016). Authoritative school climates are characterized by two essential dimensions: Disciplinary structure or the idea that school rules are perceived as strict but fairly enforced, and student support which refers to student perceptions that their teachers and other school staff members treat them with respect and want them to be successful (Cornell et al. 2016).

Attachment theory (Bowlby 1969; Cassidy and Shaver 2016) and mentalization theory (Fonagy et al. 2004; Bateman and Fonagy 2012) are two, somewhat overlapping empirically based models that shed light on the link between relationship quality and bullying. Attachment theory is a biopsychosocially informed model that focuses on the short- and long-term dynamics between humans. This model is based on the understanding that all human infants need to attach to a caregiver to survive and thrive. And, the nature of this attachment (e.g., “secure,” “anxious-ambivalent,” “anxious-avoidant,” or “disorganized”) shapes interpersonal life. Mentalization refers to the ability to understanding the mental states of oneself and others, which shapes our overt behavior. Mentalization can be understood as “thinking about thinking”—automatically, consciously, and/or in unrecognized ways. Mentalizing and attachment experiences influence one another. Individuals with disorganized attachment style (e.g., due to physical, psychological, or sexual abuse), for example, can have greater difficulty developing the ability to mentalize (Taubner 2015). Early childhood exposure to mentalization can protect the individual from psychosocial adversity (Fonagy and Bateman 2006). This early childhood exposure to genuine parental mentalization fosters the development of mentalizing capabilities in children themselves (Rosso et al. 2015; Scopesi 2015).

We suggest that Bowlby’s (1969) attachment theory as well as Fonagy and Bateman’s (Fonagy et al. 2004) mentalization theory can help shedding light on the link between relationship quality and bullying. Students with secure attachment—i.e., secure inner working models of positive relationships they developed during early childhood with the help of emotionally responsive and securely attached primary caregivers—are more likely to develop the social skills necessary for establishing and maintaining positive relationships (Seifert 2016). During ongoing positive social interactions with their parents, teachers, and peers at kindergarten and school, these students are able to further advance their cognitive and affective mentalization skills, i.e., the ability to put themselves into others shoes cognitively and emotionally, which is closely linked to stronger feelings of empathy and, thus, less bullying (Taubner 2015; Twemlow and Sacco 2011). Empirical research provides support for this theory. In a sample of 104 German adolescents, Taubner et al. (2013) found that the relationship between psychopathy and aggression is moderated by attachment-related mentalization. In another sample of 148 mostly White American adolescents Murphy et al. (2017) find significant relationships between direct bullying involvement as perpetrators and lower attachment to parents and peers, and between defending victims of bullying and higher attachment to parents and peers. A three-way interaction term in their regression analyses suggests that, for male adolescents, higher peer attachment might function as a protective factor against bullying involvement when parental attachment is low.

Similarly, it has been suggested that the negative consequences of traumatic early childhood experiences among some students, which are often externalized as negative behavior, can be partially mended by positive relationship experiences later in life, e.g., with specialized teachers who are able to take on the role of parental figures while retaining a high level of professionality and self-reflection (Zimmermann 2016). In sum, secure attachment and advanced mentalization skills among teachers and students help to theoretically and empirically explain why classrooms with better relationship climates are expected to have lower levels of bullying behavior.

An additional explanation for the link might be that students with better relationship experiences feel a greater sense of social responsibility (Ahmed 2006). Indeed, school-connectedness predicts lower levels of peer victimization (O’Brennan 2010), and while most students report that they do not get involved in bullying, a small number of students indicate that they try to defend the victims (Waasdorp and Bradshaw 2018). As a result, it can be expected that schools with better student-teacher and student-peer relationships have less bullying because more students feel a responsibility to defend its victims.

Social Habitus, Relationship Climates, and Bullying

Students from lower SES family backgrounds might be more involved in bullying dynamics because they have greater trouble socially adjusting to schools than their higher status peers (Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton 2016). Qualitative research has found that lower SES and working-class parents have more conflict with teachers due to class-based differences in expectations and misunderstandings (Lareau 2011) and explain these findings with Pierre Bourdieu’s (1990) social habitus concept. According to this theory, people from the same social classes tend to share cultural expectations and behavioral habits. Teachers and school administrators most commonly share a White middle-class habitus. As a result, students from lower and working classes, or from ethnic minority backgrounds, have a greater cultural (habitus) gap to bridge, leading to less cordial relationships with teachers and school administrators. Given that the quality of relationships in schools are negatively related to bullying dynamics (Longobardi et al. 2017; Maunder and Crafter 2018), it is possible that a habitus mismatch between disadvantaged students and teachers manifests itself in poorer relationship climates in schools with higher percentages of lower SES and ethnic minority students, leading to higher levels of bullying behavior.

Some quantitative studies support the idea of a habitus mismatch. Specifically, lower SES students tend to feel less connected to schools than higher SES peers (Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton 2016), and students with lower school-connectedness have been found to be more involved in bullying dynamics (O’Brennan 2010). In addition, lower SES and ethnic minority students have been found to not only feel more disconnect from schools (Sampasa-Kanyinga et al. 2019) but are also more likely to worry that they are perceived as less intelligent by student peers, which mediates the relationship between their family SES background and bullying behavior (Dietrich and Ferguson 2019).

Study Purpose

Students’ SES family background (Due et al. 2009; Tippett and Wolke 2014), students’ ethnic identity (Nguy 2004; Psalti 2007; Scherr et al. 2010), and the teaching quality in classrooms (Dietrich and Hofman 2019; Roth 2011) are significant predictors of students’ bullying behavior. Furthermore, the quality of relationships in schools has been found to predict bullying among students (Maunder and Crafter 2018). Hence, this study proposes the hypothesis that the link between classroom-level bullying and three classroom-level factors—students’ SES background, students’ ethnicity, and teaching quality—can be statistically explained by the quality of student-teacher and student-student relationships (STR and SSR). The classroom level of analysis was chosen because an Inter-Correlation-Coefficient analysis has shown that 70% more variance of the bullying outcome variable in this study can be explained at the classroom than the school level. A student-level analysis was ruled out, because the teaching quality measures in this study, the Tripod 7Cs, have only been shown to be valid and reliable at the classroom level.

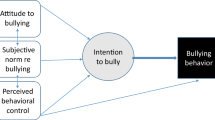

Specifically, this study hypothesizes that students’ SES, being White versus being a student of color, and teaching quality in the classroom predict the quality of STR and SSR in the classroom, which in turn predict students’ bullying (see Fig. 1). In addition, direct paths from SES and being White to teaching quality are expected because the classroom composition in terms of SES (Kane and Cantrell 2010) and ethnicity (Jackson 2009) has been found to predict the quality of teaching in class. A direct path from STR to SSR is also hypothesized because, in accordance with Bandura’s social learning theory (Bandura 1977), the way teachers treat students has been found to influence how students treat each other (Chory and Offstein 2018; Hughes et al. 1999). SES, being White, and teaching quality may also have direct paths to bullying, because STR and SSR might not explain the entire relationship between these three classroom-level factors and bullying. Students being White and SES background are allowed to covary because of the strong historic link between ethnicity and SES in the USA (Shapiro 2017; Williams et al. 2016).

Methods

Participants

The sample of this study is based on the Tripod student survey created and administered by Tripod Education Partners, an American educational research firm (Tripod Education Partners 2019). The Tripod student survey is conducted annually in primary and secondary schools in all major regions of the USA and asks students a large variety of questions on school-related topics, including teachers’ instructional skills, the quality of students’ relationships with teachers, the quality of students’ relationships among each other, students’ social behaviors, and students’ family background characteristics. Schools in the Tripod sample are typically either part of a public school district or private charter school network, which hired Tripod Education Partners for the primary purpose of providing teachers with student feedback about their teaching quality. Hence, some schools collect Tripod survey data voluntarily, while most schools’ participation is required. Participants are all students who were at school the day the Tripod survey was scheduled by the respective school.

The study sample was collected in grades 5 through 12 during the academic years 2012–2015. The total N is 146,044 students from 7247 classrooms, 131 schools, and 29 districts. Overall, the sample has a balanced gender ratio (50% female and 50% male), but with 30% White students and 70% students of color, it is notably more diverse than the overall American student population (National Center for Education Statistics 2019). This is not unexpected because the Tripod student survey is primarily used for school improvement purposes and, thus, should be more prevalent in lower performing school districts, which tend to be ethnically more diverse and less wealthy (Reardon et al. 2019).

Procedures

Schools primarily use the Tripod survey results to provide their teachers with detailed feedback on students’ views on the quality of their teaching, measured by the Tripod 7Cs Framework of Effective Teaching, and in some schools and districts, the 7Cs scores are even used for teacher evaluations and factored into teacher salaries. Tripod surveys are conducted school-wide and administered online or via pen and paper, and they are completely confidential. Most survey participants filled in the surveys on the day their schools administered them in the entire school, but in a few cases, students were permitted to complete and hand in their survey responses later.

Instruments

Bullying

Student bullying is a two-item factor from the Tripod student survey (Tripod Education Partners 2016) and measures to what degree students believe others perceive them as bullies/intimidating. Both items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Totally True) to 5 (Totally Untrue) and read “Other students think I am a bully” and “Some teachers seem afraid of me.” Before inserted into the model, the items were aggregated to the classroom level. Internal validity has been previously confirmed via multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (ML-CFA) (Dietrich and Zimmermann 2019). Even though the bullying factor does not measure actual bullying behavior, which is practically impossible to establish on a very large scale, it is a valuable proxy that has been found to be a significant predictor of students’ self-perceived victimization rates in schools (Dietrich and Ferguson 2019).

Student-Student and Student-Teacher Relationships

The quality of student-teacher and student-student relationships are two latent factors based on three items each. The STR-items are the following: respects_t (“I treat the adults at this school with respect, even if I don’t know them”), t_respect (“Teachers in the hallways treat me with respect, even if they don’t know me”), and quiet_down (“I would quiet down if someone said I was talking too loudly in the hallway.”) The SSR-items are as follows: pressure (“I do things I don’t want to do because of pressure from other students”), fight (“At this school, I must be ready to fight to defend myself”), and popular (“Trying to be popular sometimes distracts me from my work in this class”), which have been reverse-coded to measure higher quality SSR. All six relationship items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Totally True) to 5 (Totally Untrue). Before inserted into the model, the items were aggregated to the classroom level. Both factors’ construct validity has been previously confirmed via ML-CFA (Dietrich 2019).

Teaching Quality

Teaching quality is measured by the 7Cs composite, an index based on the Tripod 7Cs Framework of Effective Teaching (Tripod Education Partners 2016). The 7Cs composite consists of the Tripod 7Cs indices, which are averages of a total of 34 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Totally True) to 5 (Totally Untrue).

To calculate the 7Cs indices, all 34 items are first aggregated to the classroom level, then averaged as follows: Care has 3 items and α = .79 in this dataset, Confer has 3 items and α = .79, Captivate has 4 items and α = .85, Clarify has 9 items and α = .90, Consolidate has 3 items and α = .76, Challenge has 5 items and α = .81, and Classroom Management consists of 7 items and α = .84. The 7Cs composite is calculated as the mean of the 7Cs indices and α = .92 in this dataset; higher values indicate better teaching quality. Validity and reliability of the 7Cs Composite at the classroom level are well-established (Cantrell and Kane 2013; Polikoff 2016).

Socioeconomic Status

The SES-index in the Tripod survey consists of three items: the number of books at home (5-point Likert scale), the number of computers at home (4-point Likert scale), and the highest educational level among students’ parents (5-point Likert scale). All three items were standardized and aggregated to the classroom level for the analysis. Construct validity of this index has been previously confirmed via the ML-CFA (Dietrich and Zimmermann 2019).

Ethnicity

Student ethnicity is a bivariate variable, 1 for being White, 0 for being a student of color or multiethnic. This measure is based on students’ self-perceptions, who choose from a wide range of identities, including White, Black, Latino/a, Asian, Native American/Pacific Islander, and Arab/Middle Eastern. Multiple answers are permitted in the Tripod survey. For the analysis, the variable was aggregated to the classroom level, transforming it into percentages of White students in the classroom.

Analyses

In order to test the proposed hypotheses, this study uses Mplus 8 to apply multilevel structural regression modeling (ML-SRM) because it permits complex path modeling analyses with nested data and latent factors (Kline 2011). In order to compare model fit, the study uses and presents χM2, SRMR, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA statistics. The recommended cutoffs for these statistics are from Hu (1999): RMSEA and SRMR should be < 0.08, CFI and TLI should be > 0.90. All endogenous variables are tested for acceptable kurtosis (< 7) and skewness (< 2), as required by maximum likelihood estimation. The significance of mediation effects is estimated via the normality approach, which is more conservative than bootstrapping and, thus, more prone to type 2 errors (Preacher and Hayes 2004). However, this shortcoming is more than compensated for by the study’s very large sample size. All results in this study will be reported in effect sizes, as calculated by the Mplus 8.

Missing Data

Table 1 summarizes missing values of all items. The analyses apply full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) to handle missings, which is considered a superior approach to more time-consuming multiple imputation approaches commonly applied in multiple regression studies (Allison 2012).

Results

Figure 2 shows the final path model with the best fit statistics (χM2 = 3984.967, CFI = 0.987, TLI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.022, SRMR = 0.029), which are well within the acceptable range of Hu and Bentler’s (Hu 1999) recommendations. The main hypothesis can be confirmed: Students’ socioeconomic status, percentage of White students, and teaching quality have direct and/or indirect paths to the quality of student-teacher and student-student relationships, which in turn have direct paths to bullying. Teaching quality and the percentage of White students both have no direct path to bullying, suggesting that STR and SSR explain the entire relationship between White/teaching quality and bullying. Students’ SES shows a direct path to bullying (standardized coefficient = 0.07, p < 0.001) but with a reverse (positive) sign, meaning that STR and SSR over-explain the negative relationship between SES and bullying.Footnote 2 In other words, students from higher SES backgrounds report that they more strongly believe that they are bullies in the eyes of others than students from lower SES backgrounds, holding the quality of relationships in school constant.

Final ML-SR model: classroom-level SES and teaching quality as predictors of bullying, mediated by the quality of student-teacher and student-student relationships (STR and SSR). Model fit statistics: χM2 = 3984.967; CFI = 0.987; TLI = 0.982; RMSEA = 0.022; SRMR = 0.029. All paths are statistically highly significant (p < 0.001), except for the path from White to teaching quality, which is only significant (p < 0.05)

As expected, the quality of SSR in classrooms has the strongest direct path to bullying with a large and negative effect size (standardized coefficient = − 0.87, p < 0.001), followed by STR with a small and negative effect size (standardized coefficient = − 0.16, p < 0.001), and SES with a tiny positive effect size (standardized coefficient = 0.07, p < 0.001). The strongest direct path to the quality of SSR is the quality of STR with a medium and positive effect size (standardized coefficient = 0.45, p < 0.001), indicating that teachers might have a notably positive impact on how students treat each other if they are skilled in establishing positive relationships with them. An alternative explanation of this link might be that poor SSR negatively impacts the quality of STR. Both explanations are not mutually exclusive and should be tested with longitudinal data in future research.

SES also has a positive path to SSR (standardized coefficient = 0.10, p < 0.001) and White (standardized coefficient = 0.09, p < 0.001), but even their combined effect to SSR is less than half of the effect of STR to SSR. In other words, teachers’ skills in establishing positive relationships with students are probably more important for positive relationship climates in classrooms than students’ SES and ethnic family background composition.

The very small to tiny but statistically significant positive paths from SES (standardized coefficient = 0.10, p < 0.001) and White (standardized coefficient = 0.02, p < 0.05) to teaching quality suggest that students’ family background might influence teaching quality in classrooms. This might be explained by the finding that disadvantaged students, such as lower SES students and students of color, self-report more misbehavior than higher SES and White students, making teaching more difficult (Ferguson 2016). Lastly, both links are further evidence supporting the theory of a habitus-mismatch between teachers and students of color or lower SES family background.

Discussion and Practical Implications

Frequent bullying behavior of students is a serious challenge in many schools, and in particular in those where students are predominantly from lower SES (Due et al. 2009; Tippett and Wolke 2014) or ethnic minority (Nguy 2004; Psalti 2007; Scherr et al. 2010) family backgrounds. In accordance with Bordieu’s (Bourdieu 1990) habitus theory, the findings of this study confirm this pattern and suggest that one effective way to effectively reduce bullying might be to improve teachers’ skills in establishing positive relationships with students, in particular those from disadvantaged family backgrounds. The findings also concur with research results from Wang et al. (2015), which suggest that better student-teacher relationships might lead to stronger anti-bullying attitudes among students and in turn, less bullying.

However, additional research using longitudinal data is required to test the causal directionality of the paths in this study’s final model. For the purpose of developing effective bullying intervention practices for adolescents who attend ethnically diverse schools in low-SES neighborhoods, future research needs to explore whether the negative link between students’ bullying and better teacher relationships might happen explicitly (e.g., teachers successfully convince students that bullying is not OK), or implicitly (e.g., teachers successfully model positive relationships, which leads to students automatically and unconsciously adopting pro-social and anti-bullying attitudes), or both.

Another question remains about how teachers can improve their relationship-building skills. Research on empathic discipline can provide some insight. Okonofua et al. (2016b) have theorized that from day one on, teachers and certain student of color groups enter the classroom with preconceived negative notions about each other. Specifically, teachers expect that certain students of color to misbehave and, thus, learn to apply punitive strategies in their desperate and unsuccessful attempts to control them. Simultaneously, the negatively stereotyped students of color expect their teachers to treat them particularly unfairly and harshly and therefore misbehave and rebel against this perceived injustice. The result is a self-fulfilling prophecy fueled from both sides, teachers and students of color, leading to disproportionate expulsion rates for “difficult” students of color groups (US Department of Education 2014), and to burnout syndromes among chronically overwhelmed teachers (Ozkilica and Kartal 2012; Aloe et al. 2014).

Fortunately, disciplinary punishments can be strongly reduced with an empathic mindset intervention (Okonofua et al. 2016a). Particularly, they were able to cut students’ expulsion rates in half after convincing teachers of the idea that misbehavior among students could be the result of feelings of insecurity and peer pressure, not ill will. Okonofua et al. infer from their findings that teachers are less likely to use punishment as a means to control students and instead apply more empathetic strategies that value students’ perspectives. In turn, students feel more fairly treated and misbehave less. This disproves teachers’ negative expectations and leads to better student-teacher relationships.

Historically, elementary school teachers have focused on their relational abilities in pre-service learning. However, high school teachers have not. Pre-service learning for high school teachers tends to focus on their content area (e.g., science or language arts) alone. Over the last three decades, there have been a range of ways that educators and school-based mental health professionals have worked to promote classroom, building, and district leaders’ relational abilities in the USA: Annenberg foundation’s Critical Friends Groups (Bambino 2002) to Parker Palmer’s Courage to Teach professional development efforts (Center for Courage and Renewal 2019) to Japanese Lesson Study (Lesson Study Group 2019) to even more formal leadership development efforts, including the Academy for Social Emotional Learning (2019), the CARE (Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education) program (CREATE for Education 2019), and the National School Climate Center’s School Climate Leadership program (NSCC n.d.). As interest in social emotional learning and school climate is increasing around the world, there is growing interest in adult social, emotional, and civic learning.

School-based (and other) mental health professionals have—generally—been even more attuned to the importance of their being involved with ongoing adult professional development that supports and promotes their relational capacities. In fact, there is an implicit social norm that supports mental health professionals being involved with ongoing supervisory and/or professional development efforts throughout their post-graduate learning. The findings in this paper suggest that education leaders, schools, and teachers might want to take another close look at this idea for the purpose of student-teacher relationships.

The findings of this paper also indicate that bullying might be effectively reduced with school intervention efforts that target student-student relationships directly, although additional research is needed to evaluate whether the link from student-student relationships to bullying is indeed causal. Divecha and Brackett (2019) argue that bullying prevention programs require a shift towards evidence-based practices of social-emotional learning (SEL) in order to become more effective, and refer to meta-analytic analyses to support their case (Durlak et al. 2011). These suggest that social-emotional learning improves relationships and reduces bullying. In addition, the authors note that SEL programs designed for students can also have positive effects on teachers’ social emotional skills and well-being (Domitrovich et al. 2016; Schonert-Reichl 2017).

Tzani-Pepelasi et al. (2019) propose the idea that peer mentoring programs might effectively improve student-student relationships and reduce bullying. In their research, they introduce the so-called buddy approach, in which older students take on the role of mentor of younger students and provide structured peer support. According to their qualitative results based on semi-structured interviews with students, the buddy approach “[…] improves students’ sense of friendships, safety, belonging, and protection […]” (Tzani-Pepelasi et al., p. 111). However, the authors also warn that the buddy approach has not yet been tested with adolescents and therefore be implemented with caution at the secondary school level.

The findings from this study underscore the growing research-based understanding that learning happens in relational contexts (Berman et al. 2018; Jones and Kahn 2017). Developmental systems theories and findings from neuroscience, developmental science, epigenetics, early childhood, psychology, adversity science, resilience science, the learning sciences, and the social sciences underscore that complex relational systems shape development and learning (Osher et al. 2018). Yet, to a great extent in educational policy and practice, leaders around the world have and continue to focus on instructional efforts alone. Our quest to identify “evidence-based” curriculum and instruction has been understandable, but narrow in focus. Historically, educational practice and research leaders have focused on instruction. Over the last dozen or so year, there has been a growing appreciation that we need to recognize and promote systemically as well as instructionally informed improvement efforts to further effective and sustainable pro-social (e.g., SEL, school climate, character education, and mental health promotion) and school safety efforts (Cohen and Espelage 2020). There are a range of important systemically informed improvement goals that are relevant to school safety efforts including: indicators for success; the nature of leadership development efforts for students as well as educators; district and state policy; how iterative and continuous learning (individual, school, and between schools) is supported; codes of conduct, rules, and social norms; and the major themes and rituals that help to shape school life (Cohen et al. 2009; National School Climate Council 2015; Thapa et al. 2013).

There is no simple or “correct” way to conceptualize the multitude of variables that color and shape individual and organizational life. This study supports the notion that in addition to our needing to recognize and focus on systemic and instructional factors and processes that we need to always pay attention to relational processes and goals (National School Climate Council 2015).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study has several limitations. First, the analyses are based on cross-sectional data, which means that paths could not be evaluated for causality of effect. Future research could test the link between SSR and STR, the links between these two relationship factors and student bullying behavior, and the link between teaching quality and STR for directionality of effect. For example, improving teachers’ relationship-building skills might lead to better teaching quality, better teaching quality might lead to better relationships, or both. This focus overlaps with the recent final The Aspen Institutes’ report (2019) from the National Commission on Social Emotional and Academic Development: Effective and sustainable SEL, school climate, and school safety improvement efforts need to be grounded in ongoing educator/adult SEL informed learning about student development and the nature of learning. These research findings, we hope, will inform educational policy and practice leaders about the importance of teacher professional development training for better teaching skills as well as developmentally informed understandings that can be expected to improve the relationship climate in schools and thus, reduce bullying.

Second, all data are based on student perceptions. However, while students’ objectivity can be contested, it has been convincingly argued that self-perceptions are more important than “objective reality” when it comes to explaining social phenomena, such as bullying behavior and interpersonal relationships (Glei et al. 2018).

Third, the outcome factor of bullying consists of only two items, and students do not read a common definition of bullying before filling in the Tripod survey’s bullying question. More items might have been preferable (Kline 2011), but are not available in the Tripod dataset; a common bullying definition would have increased the outcome variable’s reliability. This being said, previous research has supported the validity of the Tripod bullying variable “other students think I am a bully,” showing that its school aggregate is a significant predictor of students’ school-level reporting of victimization (Dietrich and Ferguson 2019). In other words, the more strongly students in a school belief they are perceived by others as bullies, the more strongly students of the same school report that they perceive themselves as victims of bullying.

Fourth, the factor SSR does not measure the quality of student-student relationships directly. All three items of SSR are only proxies of poor student-student relationship climates.

Fifth, the analyses of this study were conducted with data collected from adolescents only. Future research should test this study’s proposed final model with data collected among children. Important differences to adolescents can be expected. Relationships with adults are more important for explaining children’s behavior, peer relationships more important for explaining adolescent behavior (Branje 2018). Hence, the quality of student-teacher relationships might be a stronger predictor of bullying among children while, in contrast, the quality of student-student relationships might be a stronger predictor of bullying behavior among adolescents.

Sixth, future research could explore the unexpected result that students from higher SES backgrounds bully more than students from lower SES backgrounds when the quality of relationships in schools is held constant. One possible explanation is that higher SES students are raised to be more competitive than lower SES students, which can in turn lead to more stress and aggression (Hamid and Shah 2016; Llorca et al. 2017). Both emotions have been linked to more bullying behavior (Dietrich and Zimmermann 2019; Kampoli et al. 2017). Another explanation is that there is a power imbalance between higher and lower SES students in peer groups, which provides higher SES students with more opportunities of relational bullying through the peer group.

Finally, this study has focused on classroom-based relationships and instruction. As noted above, person-to-person and classroom experiences are always “nested” within larger systems, school, district, and community life.

The results of this study support the understanding that the relationships between bullying and student family background, in terms of SES and ethnicity, and between bullying and teaching quality, are entirely mediated by differences in the quality of relationships in classrooms between students and teachers, as well as students and their peers, in accordance with Bourdieu’s (1990) habitus theory. Consequently, schools with severe bullying problems, often those with high percentages of lower SES students and students of color, are well-advised to focus teachers’ professional development training on teachers’ social-emotional and relationship-building skills.

Change history

12 July 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00133-x

Notes

In the USA, the word race is commonly differentiated from ethnicity, but not in Europe. This paper follows European convention.

SES and bullying involvement are typically negatively correlated when other factors, such as quality of relationships, are not statistically controlled for. This is also true in this study’s dataset.

References

Academy for Social Emotional Learning (2019). Academy for social emotional learning in schools.

AERA. (2013). Prevention of bullying in schools, colleges, and universities: research report and recommendations. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.aera.net/Portals/38/docs/News%20Release/Prevention%20of%20Bullying%20in%20Schools,%20Colleges%20and%20Universities.pdf

Ahmed, E. (2006). ‘Stop it, that’s enough’: bystander intervention and its relationship to school connectedness and shame management. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 3(8), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450120802002548.

Allen, K. (2010). Classroom management, bullying, and teacher practices. The Professional Educator, 34(1).

Allison, P. (2012). Why maximum likelihood is better than multiple imputation. Retrieved from https://statisticalhorizons.com/ml-better-than-mi

Aloe, A. M., Shisler, S. M., Norris, B. D., Nickerson, A. B., & Rinker, T. W. (2014). A multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout. Educational Research Review, 12, 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.003.

Arseneault, L., Milne, B. J., Taylor, A., Adams, F., Delgado, K., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2008). Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children’s internalizing problems: A study of twins discordant for victimization. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(2), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53.

Atlas, R. S., & Pepler, D. J. (1998). Observations of bullying in the classroom. Journal of Educational Research, 92(2), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220679809597580.

Baldwin, J. L., Arseneault, L., & Danese, A. (2015). Childhood bullying and adiposity in young adulthood: findings from the E-Risk Longitudinal Twin Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 61(11), 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.431.

Bambino, D. (2002). Critical friends. Educational Leadership, 59(6), 25–26.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press.

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. 2012. Handbook for mentalizing in mental health practice (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611.

Berman, S., Chaffee, S., & Sarmiento, J. (2018). The practice base for how we learn: supporting students’ social, emotional, and academic development. Retrieved from https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2018/03/CDE-Practice-Base_FINAL.pdf.

Bernotaite, L., & Malinauskiene, V. (2017). Workplace bullying and mental health among teachers in relations to psychosocial job characteristics and burnout. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 30(4), 629–640. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00943.

Bogart, L. M., Elliott, M. N., Klein, D. J., Tortolero, S. R., Mrug, S., Peskin, M. F., Davies, S. L., Schink, E. T., & Schuster, M. A. (2014). Peer victimization in fifth grade and health in tenth grade. Pediatrics, 133(3), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3510.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). Structures, habitus, practices. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Branje, S. (2018). Development of parent-adolescent relationships: conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12278.

Campbell, M. (2018). The magic of building student-teacher relationships. ASCD Express, 14(1).

Cantrell, S., & Kane, T. J. (2013). Ensuring fair and reliable measures of effective teaching: culminating findings from the MET project’s three-year study. Retrieved from Seattle, WA: https://www.edweek.org/media/17teach-met1.pdf

Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Handbook for attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Chory, R. M., & Offstein, E. H. (2018). Too close for comfort? Faculty–student multiple relationships and their impact on student classroom conduct. Ethics & Behavior, 28(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1206475.

Cohen, J., & Espelage, D. (2020). Creating safe, supportive and engaging schools: challenges and opportunities around the world: Harvard Education Press.

Cohen, J., McCabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: research, policy, teacher education and practice. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180–213.

Cornell, D., & Huang, F. (2016). Authoritative school climate and high school student risk behavior: a cross-sectional multi-level analysis of student self-reports. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(11), 2246–2259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0424-3.

Cornell, D., Huang, F., Konold, T., Malone, M., Datta, P., Stohlman, S., . . . Meyer, J. P. (2016). Development of a standard model for school climate and safety assessment: final report. Retrieved from Charlottesville, VA: https://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/FInal_Report_Grant_for_2012-JF-FX-0062.pdf

Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (1997). Observations of bullying and victimization in the schoolyard. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 13(2), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/082957359801300205.

Craig, W. M., Pepler, D. J., & Atlas, R. (2000). Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International, 21(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034300211002.

CREATE for Education (2019). Care for teachers. Retrieved from https://createforeducation.org/care/

Dietrich, L. (2019). Akademisches Schikanieren: Wie Lehrkräfteprofessionalisierung in den Bereichen Beziehungsarbeit und Lehrqualität zu sozioökonomischer Chancengleichheit im Bildungswesen beitragen kann. Empirische Sonderpädagogik, 3, 241–256.

Dietrich, L., & Ferguson, R. F. (2019). Why stigmatized adolescents bully more: the role of self-esteem and academic-status insecurity. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1622582.

Dietrich, L., & Hofman, J. (2019). Exploring academic teasing: Predictors and outcomes of teasing for making mistakes in classrooms. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1598449.

Dietrich, L., & Zimmermann, D. (2019). How aggression-related mindsets explain SES-differences in bullying behavior. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1591032.

Divecha, D., & Brackett, M. (2019). Rethinking school-based bullying prevention through the lens of social and emotional learning: a bioecological perspective. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00019-5.

Domitrovich, C. E., Bradshaw, C. P., Berg, J. K., Pas, E. T., Becker, K. D., Musci, R., Embry, D. D., & Ialongo, N. (2016). How do school-based prevention programs impact teachers? Findings from a randomized trial of an integrated classroom management and social-emotional program. Prevention Science, 17(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0618-z.

Due, P., Merlo, J., Harel-Fisch, Y., Damsgaard, M. T., Holstein, B. E., Hetland, J., Currie, C., Gabhainn, S. N., de Matos, M. G., & Lynch, J. (2009). Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to bullying during adolescence: a comparative, cross-sectional, multilevel study in 35 countries. American Journal of Public Health, 99(5), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.139303.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Erikson, E. (1994). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Ferguson, R. F. (2016). Aiming higher together: strategizing better educational outcomes for boys and young men of color Retrieved from Washington D.C.: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/80481/2000784-Aiming-Higher-Together-Strategizing-Better-Educational-Outcomes-for-Boys-and-Young-Men-of-Color.pdf

Fisher, H. L. (2012). Bullying victimization and risk of self-harm in early adolescence: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ, 344. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2683.

Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. W. (2006). Mechanisms of change in mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20241.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2004). Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. New York, NY: Other Press.

Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2019). Examining the effectiveness of school-bullying intervention programs globally: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-0007-4.

Gastic, B. (2008). School truancy and the disciplinary problems of bullying victims. Educational Review, 60(4), 391.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 123(3), 1059–1065. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0614.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Psychiatrics, 132(4), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0614.

Glei, D. A., Goldman, N., & Weinstein, M. (2018). Perception has its own reality: subjective versus objective measures of economic distress. Population and Development Review, 44(4), 695–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12183.

Hamid, Z., & Shah, S. A. (2016). Exploratory study of perceived parenting style and perceived stress among adolescents. International Journal of Academic Research in Education and Review, 4(6), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.14662/IJARER2016.014.

Hardin, C. (2008). Effective classroom management: Models and strategies for today’s classroom (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Holt, M. K., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Polanin, J. R., Holland, K. M., DeGue, S., Matjasko, J. L., et al. 2015. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135(2), e496–e509. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1864.

Hu, L.-t.., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., & Jackson, T. (1999). Influence of the teacher-student relationship on childhood conduct problems: a prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 28(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_5.

Hunter, S. C., Durkin, K., M.Boyle, J., Booth, J. N., & Rasmussen, S. (2014). Adolescent bullying and sleep difficulties. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 10(4), 740–755. doi:https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v10i4.815.

Hyman, I. (2006). Bullying: theory, research, and interventions. In E. Emmer (Ed.), Handbook of classroom management: research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 855–884). Florence, KY: Routledge.

Imran, M., Hosen, M., & Chowdhury, M. A. F. (2018). Does poverty lead to crime? Evidence from the United States of America. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(10), 1424–1438. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-04-2017-0167.

Jackson, C. K. (2009). Student demographics, teacher sorting, and teacher quality: evidence from the end of school desegregation. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(2), 213–256. https://doi.org/10.1086/599334.

Jones, S., & Kahn, J. (2017). The evidence base for how we learn: supporting students’ social, emotional, and academic development: a consensus statements of evidence from the council of distinguished scientists. Retrieved from https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2017/09/SEAD-Research-Brief-9.12_updated-web.pdf

Kampoli, G. D., Antoniou, A.-S., Artemiadis, A., Chrousos, G. P., & Darviri, C. (2017). Investigating the association between school bullying and specific stressors in children and adolescents. Scientific Research, 8(14), 2398–2409. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2017.814151.

Kane, T. J., & Cantrell, S. (2010). Learning about teaching: Initial findings from the Measures of Effective Teaching Project. Retrieved from Seattle, WA: https://docs.gatesfoundation.org/Documents/preliminary-findings-research-paper.pdf

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Third ed.). New York, NY: The Guileford Press.

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: class, race, and family life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lee, M. R., Bankston, W. B., Hayes, T. C., & Thomas, S. A. (2007). Revisiting the southern culture of violence. The Sociological Quarterly, 48(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00078.x.

Llorca, A., Richaud, M. C., & Malonda, E. (2017). Parenting styles, prosocial, and aggressive behavior: the role of emotions in offender and non-offender adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01246.

Longobardi, C., Iotti, N. O., Jungert, T., & Settani, M. (2017). Student-teacher relationships and bullying: the role of student social status. Journal of Adolescence, 63, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.001.

Maunder, R. E., & Crafter, S. (2018). School bullying from a sociocultural perspective. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.010.

McCann, A. (2018). States with the biggest bullying problems. Retrieved from https://wallethub.com/edu/best-worst-states-at-controlling-bullying/9920/

Murphy, T. P., Laible, D., & Augustine, M. (2017). The influence of parent and peer attachment on bullying. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1388–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0663-2.

NASEM. (2016). Preventing bullying through science, policy, and practice. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

National School Climate Council (2015). School climate and prosocial educational improvement: essential goals and processes that support student success for all. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325178158_School_Climate_and_Pro-social_Educational_Improvement_Essential_Goals_and_Processes_that_Support_Student_Success_for_All

NCES. (2019). Indicator 6: Elementary and Secondary Enrollment. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_rbb.asp

Nguy, L. (2004). Ethnicity and bullying: a study of Australian high-school students. Educational and Child Psychology, 21(4), 78.

Nieto, S., & Ramos, R. (2015). Educational outcomes and socioeconomic status: a decomposition analysis for middle-income countries. PROSPECTS, 45, 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-015-9357-y.

NSCC. (n.d.). Leadership development. Retrieved from https://www.schoolclimate.org/services/educational-offerings/leadership-development

O’Brennan, L. (2010). Relations between students’ perceptions of school connectedness and peer victimization. Journal of School Violence, 9(4), 375.

OECD. (2017a). Bullying. In O. f. E. C.-o. a. Development (Ed.), PISA 2015 Results (Vol. III, pp. 133-152). Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2017b). Understanding the socio-economic divide in Europe. Retrieved from http://oe.cd/cope-divide-europe-2017

Okonofua, J. A., Paunesku, D., & Walton, G. (2016a). Brief intervention to encourage empathic discipline cuts suspension rates in half among adolescents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(19), 5221–5226. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523698113.

Okonofua, J. A., Walton, G. M., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2016b). A vicious cycle: a social-psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635592.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: how relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 1-31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650.

Ozkilica, R., & Kartal, H. (2012). Teachers bullied by their students: how their classes influenced after being bullied? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 3435–3439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.080.

Payne, A. A., & Gottfredson, D. C. (2004). Chapter 7-schools and bullying: school factors related to bullying and school-based bullying interventions. In C. E. Sanders & G. D. Phye (Eds.), Bullying: implications for the classroom (pp. 159–176). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Perkins, H. W. (2003). The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: a handbook for educators, counselors, clinicians. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pervin, K., & Turner, A. (1998). A study of bullying of teachers by pupils in an inner London school. Pastoral Care in Education, 16(4), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0122.00104.

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65.

Polikoff, M. S. (2016). Evaluating the instructional sensitivity of four states’ student achievement tests. Educational Assessment, 21(2), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2016.1166342.

Ponzo, M. (2013). Does bullying reduce educational achievement? An evaluation using matching estimators. Journal of Policy Modeling, 35(6), 1057.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553.

Psalti, A. (2007). Bullying in secondary schools. The influence of gender and ethnicity. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 14(4), 329.

Reardon, S. F., Kalogrides, D., & Shores, K. (2019). The geography of racial/ethnic test score gaps. The American Journal of Sociology, 124(4), 1164–1221. https://doi.org/10.1086/700678.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., Boelen, P. A., van der Schoot, M. V., & Telch, M. J. (2011). Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 37(3), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20374.

Rosso, A. M., Viterbori, P., & Scopesi, A. (2015). Are maternal reflective functioning and attachment security associated with preadolescent mentalization? Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1–12).

Roth, G. (2011). Prevention of school bullying: the important role of autonomy-supportive teaching and internalization of pro-social values. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(4), 654.

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., & Hamilton, H. A. (2016). Does socioeconomic status moderate the relationships between school connectedness with psychological distress, suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents? Preventive Medicine, 87, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.010.

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Chaput, J.-P., & Hamilton, H. A. (2019). Social media use, school connectedness, and academic performance among adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(3), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-019-00543-6.

Sanchez, E., Robertson, T. R., Lewis, C. M., Rosenbluth, B., Bohman, T., & Casey, D. M. (2001). Preventing bullying and sexual harassment in elementary schools: the expect respect model. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 2(2–3), 157.

Sass, T., Hannaway, J., Xu, Z., Figlio, D., & Feng, L. (2010). Value added of teachers in high-poverty schools and lower-poverty schools. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/33326/1001469-Value-Added-of-Teachers-in-High-Poverty-Schools-and-Lower-Poverty-Schools.PDF

Scherr, T., McCaffery, P., Jimerson, S. R., Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (2010). Bullying dynamics associated with race, ethnicity, and immigration status In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: an international perspective (pp. 223-234). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. Future of Children, 27(1), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2017.0007.

Schreier, A., Wolke, D., Thomas, K., Horwood, J., Hollis, C., Gunnel, D., et al. (2009). Prospective study of peer victimization in childhood and psychotic symptoms in a nonclinical population at age 12 years. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(5), 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.23.

Scopesi, A. (2015). Mentalizing abilities in preadolescents’ and their mothers’ autobiographical narratives. Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(4), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614535091.

Seifert, K. (2016). Attachment and the development of relationship skills. Journal of Psychology and Clinical Psychiatry, 5(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.15406/jpcpy.2016.05.00281.

Shapiro, T. (2017). Toxic inequality: how America’s wealth gap destroys mobility, deepens the racial divide, and threatens our future. New York: Basic Boocs.

Slaby, R., Wilson-Brewer, R., & Dash, K. (1994). Aggressors, victims, and bystanders: thinking and acting to prevent violence. Newton, MA: Education Development Center.

Smokowski, P. R., & Evans, C. B. R. (2019). Bullying and victimization across the life span: playground politics and power. Berlin, GER: Springer Nature. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20293-4_4.

Taubner, S. (2015). Konzept Mentalisieren. Eine Einführung in Forschung und Praxis. Gießen, GER: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Taubner, S., White, L. O., Zimmermann, J., Fonagy, P., & Nolte, T. (2013). Attachment-related mentalization moderates the relationship between psychopathic traits and aggression in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(6), 929–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9736-x.

Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(2), 357–385. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483907.

The Aspen Institute (2019). From a nation at risk to a nation at hope: recommendations from the National Commission on Social, Emotional, & Academic Development. Retrieved from http://nationathope.org/report-from-the-nation/

Theriot, M. (2004). The criminal bully: linking criminal peer bullying behavior in school to a continuum of delinquency. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 1(2/3), 77.

Tippett, N., & Wolke, D. (2014). Socioeconomic status and bullying: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), e48–e59. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301960.

Tripod. (2016). Tripod’s 7Cs framework of effective teaching. Retrieved from http://tripoded.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Guide-to-Tripods-7Cs-Framework-of-Effective-Teaching.pdf

Tripod. (2019). Learn about Tripod. Retrieved from https://tripoded.com/about-us-2/

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27–56.

Twemlow, S. W., & Sacco, F. C. (2011). Preventing bullying and school violence. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., Sacco, F. C., Gies, M. L., & Hess, D. (2001). Improving the social and intellectual climate in elementary schools by addressing bully-victim-bystander power struggles. In J. Cohen (Ed.), Caring classrooms/intelligent schools: the social emotional education of young children. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Twemlow, S., Fonagy, P., Sacco, F. C., & Brethour, J. R. (2006). Teachers who bully students: a hidden trauma. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 52(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764006067234.

Tzani-Pepelasi, C., Ioannou, M., Synnott, J., & McDonnell, D. (2019). Peer support at schools: the Buddy Approach as a prevention and intervention strategy for school bullying. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00011-z.

USDE. (2014). Civil rights data collection: data snapshot (School Discipline). Retrieved from https://ocrdata.ed.gov/downloads/crdc-school-discipline-snapshot.pdf

Uzogara, E. E., Lee, H., Abdou, C. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2014). A comparison of skin tone discrimination among African American men: 1995 and 2003. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033479.

van Geel, M., Goemans, A., & Vedder, P. H. (2015). The relation between peer victimization and sleeping problems: a meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 27, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.05.004.

Vreeman, R. C., & Carroll, A. E. (2007). A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.1.78.

Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Examining variation in adolescent bystanders’ responses to bullying. School Psychology Review, 47(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0081.V47-1.

Wang, C., Swearer, S. M., Lembeck, P., Collins, A., & Berry, B. (2015). Teachers matter: an examination of student-teacher relationships, attitudes toward bullying, and bullying behavior. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31(3), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2015.1056923.

Williams, D. R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N. (2016). Understanding associations between race, socioeconomc status and health: patterns and prospects. Journal of Health Psychology, 35(4), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242.

Williford, A., & Zinn, A. (2018). Classroom-level differences in child-level bullying experiences: Implications for prevention and intervention in school settings. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 9(1), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1086/696210.

Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2019). Does school composition moderate the longitudinal association between social status insecurity and aggression among Latinx adolescents? International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(3), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00021-x.

Yeager, D. S., Fong, C. J., Lee, H. Y., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: theory and a three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.005.

Zimmermann, D. (2016). Traumapädagogik in der Schule. Gießen, GER: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ronald F. Ferguson, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, and Tripod Education Partners, Inc., for providing the data used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dietrich, L., Cohen, J. Understanding Classroom Bullying Climates: the Role of Student Body Composition, Relationships, and Teaching Quality. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 3, 34–47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00059-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00059-x