Abstract

Objectives

Among studies of the built environment, few examine neighbourhood food environments in relation to children’s diets. We examined the associations of residential and school neighbourhood access to different types of food establishments with children’s diets.

Methods

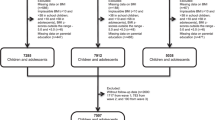

Data from QUALITY (Quebec Adipose and Lifestyle Investigation in Youth), an ongoing study on the natural history of obesity in 630 Quebec youth aged 8–10 years with a parental history of obesity, were analyzed (n=512). Three 24-hour diet recalls were used to assess dietary intake of vegetables and fruit, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Questionnaires were used to determine the frequency of eating/snacking out and consumption of delivered/take-out foods. We characterized residential and school neighbourhood food environments by means of a Geographic Information System. Variables included distance to the nearest supermarket, fast-food restaurant and convenience store, and densities of each food establishment type computed for 1 km network buffers around each child’s residence and school. Retail Food Environment indices were also computed. Multivariable logistic regressions (residential access) and generalized estimating equations (school access) were used for analysis.

Results

Residential and school neighbourhood access to supermarkets was not associated with children’s diets. Residing in neighbourhoods with lower access to fast-food restaurants and convenience stores was associated with a lower likelihood of eating and snacking out. Children attending schools in neighbourhoods with a higher number of unhealthful relative to healthful food establishments scored most poorly on dietary outcomes.

Conclusions

Further investigations are needed to inform policies aimed at shaping neighbourhood-level food purchasing opportunities, particularly for access to fast-food restaurants and convenience stores.

Résumé

Objectifs

Rares sont les études du milieu bâti qui s’intéressent aux environnements alimentaires des quartiers par rapport aux régimes alimentaires des enfants. Nous avons examiné les associations entre l’accès des quartiers résidentiels et scolaires à différents types d’établissements alimentaires et les régimes des enfants.

Méthode

Nous avons analysé les données de l’étude QUALITY (QUebec Adipose and Lifestyle InvesTigation in Youth), une étude en cours sur l’histoire naturelle de l’obésité chez 630 jeunes Québécois de 8 à 1 0 ans ayant une histoire parentale d’obésité (n=512). Trois rappels alimentaires de 24 heures ont servi à évaluer l’apport en fruits et légumes et en boissons édulcorées au sucre. À l’aide de questionnaires, nous avons déterminé la fréquence des repas et des collations pris à l’extérieur et la consommation d’aliments livrés à domicile ou à emporter. Nous avons caractérisé l’environnement alimentaire des quartiers résidentiels et scolaires au moyen d’un système d’information géographique. Les variables étaient la distance jusqu’au supermarché, au restaurant rapide et au dépanneur le plus proche, et les densités de chacun de ces types d’établissements, calculées sur un réseau tampon d’1 km autour du domicile et de l’école de chaque enfant. Des indices d’environnement alimentaire de détail ont aussi été calculés. La régression logistique multivariée (accès à partir du domicile) et des équations d’estimation généralisées (accès à partir de l’école) ont servi à l’analyse.

Résultats

L’accès des quartiers résidentiels et scolaires aux supermarchés n’était pas associé aux régimes des enfants. Le fait d’habiter un quartier où les restaurants rapides et les dépanneurs sont moins accessibles était associé à une plus faible probabilité de prendre des repas et des collations à l’extérieur. Les enfants qui fréquentaient des écoles de quartiers comptant davantage d’établissements alimentaires malsains que d’établissements sains ont obtenu les pires scores pour ce qui est de leur régime.

Conclusions

Des enquêtes plus poussées sont nécessaires pour formuler des politiques qui influencent les occasions d’achat d’aliments à l’échelle des quartiers, particulièrement l’accès aux restaurants rapides et aux dépanneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Galvez MP, Pearl M, Yen IH. Childhood obesity and the built environment: A review of the literature from 2008–2009. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010;22(2):202–7.

Rahman T, Cushing RA, Jackson RJ. Contributions of built environment to childhood obesity. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78(1):49–57.

Dunton GF, Kaplan J, Wolch J, Jerrett M, Reynolds KD. Physical environmental correlates of childhood obesity: A systematic review. Obes Rev 2009;10(4):393–402.

Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments. Disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2009;36(1):74–81.

Pearce J, Hiscock R, Blakely T, Witten K. The contextual effects of neighbourhood access to supermarkets and convenience stores on individual fruit and vegetable consumption. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62(3):198–201.

Skidmore P, Welch A, van Sluijs E, Jones A, Harvey I, Harrison F, et al. Impact of neighbourhood food environment on food consumption in children aged 9–10 years in the UK SPEEDY (Sport, Physical Activity and Eating behaviour: Environmental Determinants in Young people) study. Public Health Nutr 2010;13(7):1022–30.

Timperio A, Ball K, Roberts R, Campbell K, Andrianopoulos N, Crawford D. Children’s fruit and vegetable intake: Associations with the neighbourhood food environment. Prev Med 2008;46(4):331–35.

Jennings A, Welch A, Jones AP, Harrison F, Bentham G, van Sluijs EM, et al. Local food outlets, weight status, and dietary intake: Associations in children aged 9–10 years. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(4):405–10.

Timperio AF, Ball K, Roberts R, Andrianopoulos N, Crawford D. Children’s takeaway and fast-food intakes: Associations with the neighbourhood food environment. Public Health Nutr 2009;12(10):1960–64.

An R, Sturm R. School and residential neighborhood food environment and diet among California youth. Am J Prev Med 2012;42(2):129–35.

Casey R, Oppert J-M, Weber C, Charreire H, Salze P, Badariotti D, et al. Determinants of childhood obesity: What can we learn from built environment studies? Food Quality and Preference 2011: doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.06.003.

Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:129–43.

Gebauer H, Laska MN. Convenience stores surrounding urban schools: An assessment of healthy food availability, advertising, and product placement. J Urban Health 2011;88(4):616–22.

Kestens Y, Daniel M. Social inequalities in food exposure around schools in an urban area. Am J Prev Med 2010;39(1):33–40.

Lambert M, van Hulst A, O’Loughlin J, Tremblay A, Barnett TA, Charron H, et al. The Quebec Adipose and Lifestyle Investigation in Youth (QUALITY) cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2011;Epub July 23.

Johnson RK, Driscoll P, Goran MI. Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by doubly labeled water method in young children. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96(11):1140–44.

Health Canada. Canadian Nutrient File. Available at: https://doi.org/www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/fiche-nutri-data/cnf_downloads-telechargement_fcen-eng.php (Accessed November 15, 2011).

Health Canada. Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. A Resource for Educators and Communicators. Available at: https://doi.org/www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/index-eng.php (Accessed November 15, 2011).

Paquet C, Daniel M, Kestens Y, Leger K, Gauvin L. Field validation of listings of food stores and commercial physical activity establishments from secondary data. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:58.

Carlos HA, Shi X, Sargent J, Tanski S, Berke EM. Density estimation and adaptive bandwidths: A primer for public health practitioners. Int J Health Geogr 2010;9:39.

Lebel A, Kestens Y, Pampalon R, Thériault M, Daniel M, Subramanian SV. Local context influence, activity space, and foodscape exposure in two Canadian metropolitan settings: Is daily mobility exposure associated with overweight? J Obes 2012;2012:ID 912645. Epub 2011 Dec 28.

Spence JC, Cutumisu N, Edwards J, Raine KD, Smoyer-Tomic K. Relation between local food environments and obesity among adults. BMC Public Health 2009;9:192.

Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P, Raymond G. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Dis Can 2009;29(4):178–91.

Chaix B, Merlo J, Evans D, Leal C, Havard S. Neighbourhoods in eco-epidemiologic research: Delimiting personal exposure areas. A response to Riva, Gauvin, Apparicio and Brodeur. Soc Sci Med 2009;69(9):1306–10.

Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:125–45.

Apparicio P, Cloutier M-S, Shearmur R. The case of Montreal’s missing food deserts: Evaluation of accessibility to food supermarkets. Int J Health Geogr 2007;6(4).

Hackett A, Boddy L, Boothby J, Dummer TJB, Johnson B, Stratton G. Mapping dietary habits may provide clues about the factors that determine food choice. J Hum Nutr Diet 2008;21(5):428–37.

Laska MN, Hearst MO, Forsyth A, Pasch KE, Lytle L. Neighbourhood food environments: Are they associated with adolescent dietary intake, food purchases and weight status? Public Health Nutr 2010;13(11):1757–63.

Babey SH, Wolstein J, Diamant A. Food environments near home and school related to consumption of soda and fast food. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, 2011.

Páez A, Certes Mercado R, Farber S, Morency C, Roorda M. Relative accessibility deprivation indicators for urban settings: Definitions and application to food deserts in Montreal. Urban Studies 2012;47(7):1415–38.

Association pour la santé publique du Québec. The school zone and nutrition: Courses of action for the municipal sector. Available at: https://doi.org/www.aspq.org/documents/file/guide-zonage-version-finale-anglaise.pdf (Accessed November 15, 2011).

Charreire H, Casey R, Salze P, Simon C, Chaix B, Banos A, et al. Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: A methodological review. Public Health Nutr 2010;13(11):1773–85.

Veugelers P, Sithole F, Zhang S, Muhajarine N. Neighborhood characteristics in relation to diet, physical activity and overweight of Canadian children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2008;3(3):152–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Acknowledgements: The QUALITY study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC) and the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec. The QUALITY Residential and School Built Environment complementary studies were funded by the HFSC and the CIHR, respectively. A.Van Hulst received support from a CIHR/HSFC Training Grant in Population Intervention for Chronic Disease Prevention, and a doctoral scholarship from the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec; T. Barnett and Y. Kestens are research scholars with Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec; L. Gauvin holds a CIHR/Centre de Recherche en Prévention de l’Obésité Chair in Applied Public Health on Neighbourhoods, Lifestyle, and Healthy Body Weight; and M. Bird received a Masters’ scholarship from tine Fondation du CHU Sainte-Justine. Dr. Marie Lambert passed away on February 20, 2012. Her leadership and devotion to the QUALITY cohort will always be remembered and appreciated.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Hulst, A., Barnett, T.A., Gauvin, L. et al. Associations Between Children’s Diets and Features of Their Residential and School Neighbourhood Food Environments. Can J Public Health 103 (Suppl 3), S48–S54 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403835

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403835

Key words

- Built environment

- children

- diet

- food environment

- residential neighbourhood

- school neighbourhood

- QUALITY cohort