Abstract

Objectives

Although substantial reductions in under-5 mortality have been observed during the past 35 years, progress in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) has been uneven. This paper provides an overview of child mortality and morbidity in the EMR based on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

Methods

We used GBD 2015 study results to explore under-5 mortality and morbidity in EMR countries.

Results

In 2015, 755,844 (95% uncertainty interval (UI) 712,064–801,565) children under 5 died in the EMR. In the early neonatal category, deaths in the EMR decreased by 22.4%, compared to 42.4% globally. The rate of years of life lost per 100,000 population under 5 decreased 54.38% from 177,537 (173,812–181,463) in 1990 to 80,985 (76,308–85,876) in 2015; the rate of years lived with disability decreased by 0.57% in the EMR compared to 9.97% globally.

Conclusions

Our findings call for accelerated action to decrease child morbidity and mortality in the EMR. Governments and organizations should coordinate efforts to address this burden. Political commitment is needed to ensure that child health receives the resources needed to end preventable deaths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Creating evidence-based estimates and understanding the causes of child mortality are essential for tracking progress toward child survival goals and for planning health strategies, policies, and interventions on child health. Substantial reductions have been observed in under-5 mortality worldwide during the past 35 years, with every region in the world recording sizeable improvements in child survival (Rajaratnam et al. 2010; Lozano et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2015; You et al. 2015).

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study provides an assessment of global child morbidity and mortality, documenting child health achievements during the Millennium Development Goal era and providing estimates of child mortality by age (neonatal, post-neonatal, 1–4 years, and under-5), sex, and cause over time (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). In this manuscript, we used data from the GBD study to report child morbidity and mortality by age (neonatal, post-neonatal, 1–4 years, and under-5), sex, and cause over time in the EMR from 1990 to 2015.

This study provides the most comprehensive assessment so far of levels and trends of child morbidity and mortality in the EMR. Through a series of decomposition analyses, we identify which groups of causes contribute most to reductions in under-5 mortality across regions and the development spectrum. Comparisons of recorded levels and cause composition for child mortality by country offer an in-depth, nuanced picture of where countries might need to refocus policies and resource allocation to accelerate improvements in child survival in the future.

Millennium Development Goal 4 (MDG 4), “Reduce child mortality,” called for the reduction of the under-5 mortality rate by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015 (United Nations 2000). The new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for an end to preventable deaths of newborns and children by 2030, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1000 live births (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2017). Globally, the number of under-5 deaths has declined by 52% (from 12.7 to 5.8 million from 1990 to 2015) (GBD 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators 2016), while progress across the EMR for child survival remains uneven. Nine countries (Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and United Arab Emirates) met MDG 4 for annual reduction in child mortality of at least 4.4% between 1990 and 2015 in the EMR (GBD 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators 2016).

Neonatal deaths are the one of the largest causes of child mortality in the region, and are clearly linked to low levels of maternal health among the poorest segments of the population (Liu et al. 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF reported that less than 50% of deliveries were attended by skilled health personnel in four countries—Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen—in the year 2010. Across the region, only 31% of married women use modern contraceptives, and 35% of newborns are delivered without a skilled birth attendant present (UNICEF and WHO 2012). Beyond the neonatal period, four disorders—diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles—are the major causes of post-neonatal death (Walker et al. 2013).

The Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) is home to more than 500 million people, representing a diverse group of 22 countries, including Arab states in North Africa, Gulf nations, and countries in West Asia; 12.2% of the population are children under 5 years of age, and 20% are women of childbearing age (WHO EMRO 2013).

EMR countries have diverse historical backgrounds, political and social contexts, and fiscal and cultural influences that impact maternal and child health. The region also has wide variation in per capita gross national product (GNP), ranging from a high of $134,420 in Qatar to a low of $2000 in Afghanistan (The World Bank GNI per capita 2017a).

While the Gulf States are some of the richest countries globally, poverty rates remain high in many other countries of the EMR. The proportion of the population living below the national poverty line, according to World Bank data, is more than 20% in seven EMR countries: Afghanistan (36%), Egypt (22%), Iraq (23%), Pakistan (22%), Palestine (22%), Sudan (47%), and Yemen (35%). In five of these countries, approximately one-third of the population is also food-insecure: Afghanistan (34%), Iraq (30%), Pakistan (30%), Sudan (33%), and Yemen (36%) (The World Bank Databank 2017b). Such wide variation has a major influence on overall health spending and results in substantial health inequities both within and across countries.

Methods

The methods used to generate estimates of under-5 mortality and age-specific death rates (neonatal, post-neonatal, ages 1–4 years, and under-5), contribute to broader GBD 2015 analyses and results on all-cause mortality and cause of death. Substantial detail on data inputs, processing, and estimation methods can be found elsewhere (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). Here, we provide a brief summary of our under-5 mortality estimation approach and accompanying analyses, including an assessment of mortality trends by Socio-demographic Index (SDI), and changes in under-5 mortality attributable to leading causes of death.

Our GBD 2015 analyses follow the recently proposed Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) (Stevens et al. 2016), which include the documentation of data sources and inputs, processing and estimation steps, and overarching methods used throughout the GBD study.

Data

Data sources and types used for estimating child mortality are described extensively elsewhere (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016), but in sum, vital registration (VR) systems, censuses, and household surveys with complete or summary birth histories served as primary inputs for our analyses. Other sources, including sample registration systems and disease surveillance systems, also contributed as input data. In total we applied formal demographic techniques to 8169 input data sources of under-5 mortality from 1950 to 2015. Overall data availability and availability by source data type varied by country.

All-cause under-5 mortality and age-specific mortality

We estimated all-cause under-5 mortality and death rates by age group: neonatal (0–28 days), post-neonatal (29–364 days), and ages 1–4 years. Details on data bias adjustments for under-5 mortality, using spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression to generate a complete time series of under-5 mortality for EMR countries and the age–sex model to produce estimates of mortality for neonatal, post-neonatal, and ages 1–4 years, have been extensively discussed previously (Wang et al. 2014).

To estimate mortality by age group and sex within the under-5 categorization, we used a two-stage modeling process that has been described in detail elsewhere (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). For this analysis, we report on early neonatal and late neonatal mortality results in aggregate as neonatal mortality.

Under-5 causes of death

The methods developed and used in GBD 2015, including the systematic approach to collating causes of death from different countries; mapping across different revisions; redistributing deaths assigned to so-called garbage codes; and the overall and disease-specific cause of death modeling approaches, are described in other publications (Foreman et al. 2012; GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016).

For GBD 2015, we assessed 249 causes of death across age groups. Because of cause-specific age restrictions (e.g., no child deaths due to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias), not all causes of death were applicable for children younger than 5 years (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016).

YLLs, YLDs, and DALYs

We calculated years of life lost (YLLs) by multiplying deaths by the remaining life expectancy at the age of death from a standard life table chosen as the norm for estimating premature mortality in GBD. We consider the standard life expectancy as a composite of the best case mortality scenario for every year, age, and sex. The metric therefore highlights premature deaths by applying a larger weight to deaths that occur at younger ages. Years lived with disability (YLDs) were calculated by multiplying the number of prevalent cases of a certain health outcome by the disability weight assigned to this health outcome. A disability weight reflects the magnitude of the health loss associated with an outcome and has a value that is anchored between 0, equivalent to full health, and 1, equivalent to death. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) were calculated by adding YLLs and YLDs. Detailed methods on YLLs, YLDs, and DALYs are published elsewhere (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2016; Kassebaum et al. 2016).

Socio-demographic Index

We studied patterns in child mortality as they related to measures of socioeconomic status and development. Drawing on methods used to construct the Human Development Index (HDI) (UNDP 2016), we created a composite indicator, the Socio-demographic Index (SDI), based on equally weighted estimates of lagged distributed income (LDI) per person, average years of education among individuals older than 15 years, and total fertility rate. SDI was constructed as the geometric mean of these three values. To capture the average relationships for each age–sex group, we applied a simple least squares spline regression of mortality rate on SDI. SDI values were scaled to a range of 0–1, with 0 equaling measures of the lowest educational attainment, lowest income, and highest fertility rate between 1980 and 2015, and 1 equaling measures of the highest educational attainment, highest income, and lowest fertility rate during this time. Additional information can be found elsewhere (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016).

Decomposing change in under-5 mortality rate by causes of death

Based on the age-specific, sex-specific, and cause-specific mortality results from GBD 2015 (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016), we attributed changes in under-5 mortality rate between 1990 and 2015 to changes in leading causes of death in children younger than 5 years in the EMR during the same period. To do this, we applied the decomposition method developed by Beltran-Sanchez and colleagues (Beltran-Sanchez et al. 2008), which has also been used for other GBD analyses (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016).

Uncertainty analysis

We propagated known measures of uncertainty through key steps of the mortality estimation processes, including uncertainty associated with varying sample sizes of data, source-specific adjustments to data used for all-cause mortality, model specifications for spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression (ST-GPR) and cause-specific model specifications, and estimation procedures. Uncertainty estimates were derived from 1000 draws for under-5 mortality, age-specific mortality, and cause-specific mortality by sex, year, and geography from the posterior distribution of each step of the estimation process. These draws allowed us to quantify, and then propagate, uncertainty for all mortality metrics. Percent changes and annualized rates of change were calculated between mean estimates, while the uncertainty intervals associated with the percent changes were derived from the 1000 draws.

Results

Mortality

All-cause mortality rates for under-5 age groups in the EMR decreased from 1990 to 2015, closely following global patterns of decline of around 54% (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2017). In 2015, there were 755,843 under-5 deaths in the EMR, which constitute about 18.8% of total deaths in the region for all ages. The largest difference in under-5 deaths was in the early neonatal category, where deaths in the EMR decreased by 22.4%, in comparison to 42.4% globally (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2017). Total deaths for all under-5 age groups decreased in the EMR at a slower rate than globally (e-Table 1).

In 2015, neonatal mortality was the largest contributing group to under-5 mortality in most EMR countries (Table 1). The exceptions to this were Afghanistan, Djibouti, and Syria, with roughly equal mortality rates for neonatal, post-neonatal, and child (1–4 years) age groups, and Somalia with a child mortality rate of 44.6 (95% UI: 32.4–58.8) deaths per 1000 live births compared to a neonatal mortality rate of 31.3 (27.2–35.9) (Table 1). Somalia also had the highest under-5 mortality rate of 112.2 (97.5–130.4) deaths per 1000 live births. The United Arab Emirates had the lowest under-5 mortality rate, 5.5 (3.2–9.1) deaths per 1000 live births. Under-5 mortality rate declined annually from 1990 to 2015 in all countries, ranging from Somalia with the smallest rate of change 2.1 (1.4–2.7) to Iran with the largest 6.5 (5.2–7.9).

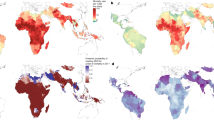

Figure 1 shows the top cause of under-5 mortality for individual countries in 2015. The top five causes of under-5 mortality—preterm birth complications, neonatal encephalopathy, lower respiratory infections, congenital defects, and diarrheal disease—were the same in the EMR and globally, with congenital defects and diarrheal diseases ranked fourth and fifth in the EMR, but fifth and fourth globally (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2017). War ranked ninth in the EMR and 25th globally (Fig. 2). From 1990 to 2015, the top five causes of under-5 mortality in the EMR remained the same. War moved from 43rd to ninth between 2000 and 2015, and measles dropped from sixth to 17th.

Changes in number of deaths and mortality rates in top 25 causes of under-5 mortality in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990–2000 and 2000–2015. Data available at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. (Global Burden of Disease 2015 study, Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990–2015)

In Afghanistan, mortality rates from nine top-10 causes were greater than the EMR average, with mortality from neonatal encephalopathy as the only exception (Table 2). Likewise, all countries except Pakistan fell beneath the average regional rate for neonatal encephalopathy, with a rate of 423.6 (318.5–528.3) per 100,000 population under 5 compared to the regional rate of 154.4 (121.7–187.9). Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and United Arab Emirates were below the average regional rates in all top-10 causes. Somalia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan had the highest mortality rates for the top 10 sub-causes of under-5 morality in 2015, while United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Kuwait had the lowest (Fig. 3).

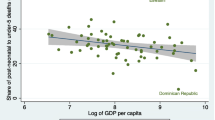

Observed mortality versus expected mortality based on SDI alone

Observed mortality rates in the EMR have been consistently lower than expected mortality rates based on SDI alone for the under-5 age group (e-Fig. 1). Kuwait had the highest observed-to-expected ratio at 1.61, followed by United Arab Emirates at 1.15 (e-Table 2). Kuwait and United Arab Emirates have the highest SDIs in the region, at 0.86 and 0.88, respectively. Djibouti, Pakistan, and Qatar also had observed-to-expected ratios greater than 1. Morocco and Palestine had the lowest ratios at 0.42 and 0.44, respectively, with SDIs at 0.5 and 0.57. Somalia, with the lowest SDI in the region, had a ratio of 0.58.

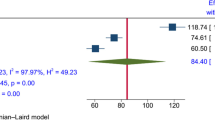

YLLs

The decrease in YLL rate per 100,000 population under 5 from 1990 to 2015 was similar globally and for the EMR, with percent decreases of about 54% (Table 3). From 1990 to 2015, YLLs decreased in all countries (Table 3). The largest decrease was in Iran, where the YLL rate decreased 81% from 132,265 (116,751–150,030) to 25,276 (18,585–33,780) per 100,000 population under 5. The smallest decrease was in Kuwait, where the YLL rate decreased 42% from 25,451 (22,873–28,223) to 14,665 (11,594–18,408) per 100,000 population under 5. Similarly, Somalia’s YLL rate decreased 43% from 380,035 (359,276–402,133) to 217,737 (188,533–253,963) per 100,000 population under 5.

YLDs

YLDs in the EMR did not track the global trend from 1990 to 2015. The under-5 YLD rate decreased by 0.6% in the EMR compared to 10.0% globally (Table 3). Five countries in the EMR had increased YLD rates (Table 3). Syria had the largest increase, 99%, followed by Yemen with a 59% increase. This increase was driven primarily by war in both countries, where it accounted for 52.4% of total YLDs in Syria and 36.9% in Yemen. The largest decrease in YLD rate was in Lebanon, a 43% decrease from 6804 (4457–10,960) to 3878 (2676–5307) per 100,000 population under 5.

DALYs

In 2015, there were 69,297,241 under-5 DALYs in the EMR, which constituted 30.2% of total DALYs in the region for all ages. From 1990 to 2015, the under-5 DALY rate in the EMR decreased by 52.8%, the same as the decrease in the global rate (Table 3). For all countries, this decrease in the DALY rate was driven primarily by a decrease in the YLL rate (Table 3). Iran had the largest decrease in DALY rate, 79%, from 137,881 (122,316–155,406) in 1990 to 29,140 (22,262–37,880) per 100,000 population under 5 in 2015. The smallest decreases were in Kuwait (40%) and Somalia (42%).

Discussion

Our study shows that progress across the region for child survival remains uneven, and total deaths for children under 5 decreased in the EMR at a slower rate than globally. Our study showed large variation in the burden by countries of the region, with about 80% of under-5 deaths occurring in six countries of the region (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen), and three countries (Sudan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan) among the 10 countries with the highest child mortality in the world (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016).

Although the top five causes of under-5 mortality—namely neonatal preterm birth complications, neonatal encephalopathy, lower respiratory tract infections (LRI), congenital defects, and diarrheal diseases—were the same globally and in the EMR, the early neonatal mortality burden still poses a huge problem in the region. The decrease in the EMR countries has been the smallest compared to other regions in the world between 1990 and 2015.

War and legal intervention ranked as the ninth cause of death in children under 5 years of age in the EMR, compared to 25th globally in 2015. This finding highlights the consequences of recent conflicts and political unrest in the region, and the wars that followed (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2017). The EMR also now carries the largest burden of displaced populations globally. Out of a total of 50 million refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) worldwide, more than 29 million (9 million refugees and 20 million IDPs) came from the region (Mokdad et al. 2016). The impact of these emergencies on public health is profound and affects both the displaced populations and host communities and usually results in food insecurity, lack of access to sanitation and health care facilities, and inadequate care. Conflicts also disrupt family, which further exacerbates child morbidity and mortality burden due to unhealthy environments, spread of disease, and decreased quantity and quality of food intake (WHO EMRO 2015).

Conflict also deteriorates child health by increasing the incidence of sexual violence against women and children. Higher rates of rape, sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancies, and unsafe abortions have been documented in previous conflicts (Akseer et al. 2015).

Poverty and economic inequity are also important determinants of child health in the EMR. A meta-analysis examined the association of poverty with infant mortality in the EMR countries and suggested that there is a significantly increased mortality risk in infants born in poor households. The results suggest that policies aimed at poverty alleviation and female literacy will substantially contribute to a decrease in infant mortality in the EMR (Cottingham et al. 2008).

Child marriage is highly prevalent in the EMR. A report showed that approximately 25% of all girls were married before the age of 18 years in 15 countries in the region (The World Bank). In four countries, Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen, the rate is estimated to be as high as 50% (The World Bank). In addition, illiteracy, especially among young females, is a common problem in the EMR. The literacy rate among females older than 15 years is approximately 80% in the EMR on average, but it is estimated to be around 67% for Morocco, 66% for Yemen, 61% for Sudan, 55% for Pakistan, and 32% for Afghanistan (The World Bank).

Our findings showed that while YLLs and DALYs followed the global trend of decrease from 1990 to 2015, YLDs in the EMR did not decrease during this period, which demonstrates the lack of improvement in socioeconomic conditions, in addition to the lack of improvement in treatments and health care facilities.

Worldwide, successes in decreasing child mortality have been attributed to rising levels of income per person (Jahan 2008; O’Hare et al. 2013); higher education, especially in women of reproductive age (Preston 1975; Gakidou et al. 2010); lower fertility rates; and strengthened public health programs.

In the EMR, action must be taken immediately to save children’s lives by expanding effective preventive and curative interventions. The health interventions needed to address the major causes of neonatal death generally differ from those needed to address other under-5 deaths, and are closely linked to maternal health. Antenatal care, delivery in a health facility attended by a skilled birth attendant, and newborn care are all essential public health measures that need to be strengthened in the EMR. In addition, global policy changes, like prevention of war and peaceful resolutions of conflicts to improve the well-being of children.

More than half of under-5 child deaths are due to diseases that are preventable and treatable through good nutrition and simple, affordable interventions. For some of the most deadly childhood diseases, such as measles, polio, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, pneumonia due to Haemophilus influenza type B and Streptococcus pneumoniae, and diarrhea due to rotavirus, vaccines are available and can protect children from illness and death (Fuchs et al. 2010). Strengthening health systems with a focus on delivery strategies and mechanisms for scaling up coverage to provide such interventions to all children is crucial to accelerate progress in improving child health in the EMR.

Health education programs, including providing information and confronting cultural and religious barriers toward utilization of family planning services, are crucial to decrease child mortality rates in the EMR. Birth spacing, decreasing the rate of high-risk pregnancies, and delaying the age of marriage, in addition to literacy, have been found to be associated with child health and survival (UNICEF 2005; Grown et al. 2005; Jain and Kurz 2007; Bhutta et al. 2013, 2014; Nasrullah et al. 2014). In addition, special care and protection should be given to vulnerable populations in war times, as well as secure shelter, food, and access to health care to prevent the devastating effects of these emergencies on child health.

Study Limitations: While our paper reports important information using the GBD methodology, this information has wide uncertainty due to absence of data or data with poor quality, and possible bias from modeling. Despite such shortcoming in the estimates produced, it provides estimates to EMR countries that could be a baseline to gauge progress of interventions. The methodology used makes the estimates comparable across countries. The EMR is going through chronic and acute turmoil that makes it difficult to observe any improvement in the future.

Conclusion

In spite of the global achievements in improving child survival across geographies, the pace of progress was slow and uneven in the EMR. Our findings reinforce the imperative need for intensive and accelerated action to decrease the burden of child morbidity and mortality in the EMR. Ministries of health, non-governmental organizations, and civic society in the region need to rise to the challenge and accelerate the pace of progress toward decreasing the unacceptably high mortality numbers among children under 5 years of age in the region. Political awareness, commitment, and leadership are needed to ensure that child health receives the attention and resources needed to end preventable child deaths.

References

Akseer N, Kamali M, Husain S et al (2015) Strategies to avert preventable mortality among mothers and children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: new initiatives, new hope. East Mediterr Health J Rev Sante Mediterr Orient Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit 21:361–373

Beltran-Sanchez H, Preston S, Canudas-Romo V (2008) An integrated approach to cause-of-death analysis: cause-deleted life tables and decompositions of life expectancy. Demogr Res 19:1323–1350. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.35

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Walker N et al (2013) Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea equitably: what works and at what cost? Lancet 381:1417–1429. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60648-0

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R et al (2014) Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 384:347–370. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3

Cottingham J, García-Moreno C, Reis C (2008) Sexual and reproductive health in conflict areas: the imperative to address violence against women. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 115:301–303. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01605.x

Foreman KJ, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ (2012) Modeling causes of death: an integrated approach using CODEm. Popul Health Metr 10:1. doi:10.1186/1478-7954-10-1

Fuchs R, Pamuk E, Lutz W (2010) Education or wealth: Which matters more for reducing child mortality in developing countries? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna, pp 175–199

Gakidou E, Cowling K, Lozano R, Murray CJL (2010) Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis. Lancet Lond Engl 376:959–974. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61257-3

GBD 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388:1725–1774. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31575-6

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388:1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388:1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1

Grown C, Gupta GR, Pande R (2005) Taking action to improve women’s health through gender equality and women’s empowerment. Lancet 365:541–543. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17872-6

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2017) Global burden of disease data visualization. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. Accessed 12 July 2017

Jain S, Kurz K (2007) New insights on preventing child marriage: A global analysis of factors programs. https://www.icrw.org/publications/new-insights-on-preventing-child-marriage. Accessed 12 July 2017

Jahan S (2008) Poverty and infant mortality in the Eastern Mediterranean region: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 62:745–751. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.068031

Kassebaum NJ, Arora M, Barber RM et al (2016) Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388:1603–1658. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X

Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S et al (2012) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379:2151–2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1

Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D et al (2015) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–2013, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 385:430–440. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6

Lozano R, Wang H, Foreman KJ et al (2011) Progress towards Millennium development goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 378:1139–1165. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61337-8

Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F et al (2016) Health in times of uncertainty in the eastern Mediterranean region, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Glob Health 4:704–713. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30168-1

Nasrullah M, Muazzam S, Bhutta ZA, Raj A (2014) Girl child marriage and its effect on fertility in Pakistan: findings from Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, 2006–2007. Matern Child Health J 18:534–543. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1269-y

O’Hare B, Makuta I, Chiwaula L, Bar-Zeev N (2013) Income and child mortality in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med 106:408–414. doi:10.1177/0141076813489680

Preston SH (1975) The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Popul Stud 29:231–248

Rajaratnam JK, Marcus JR, Flaxman AD et al (2010) Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4. Lancet 375:1988–2008. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60703-9

Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE et al (2016) Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. PLOS Med 13:e1002056. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002056

The World Bank GNI per capita, PPP (current international $) (2017a) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD. Accessed 17 May 2017

The World Bank DataBank (2017b) http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx. Accessed 17 May 2017

UNICEF (2005) Early marriage: a harmful traditional practice

UNICEF and WHO (2012) Countdown to 2015: Maternal, Newborn & Child Survival—Building a Future for Women and Children, The 2012 Report. In: ReliefWeb. http://reliefweb.int/report/world/countdown-2015-maternal-newborn-child-survival-building-future-women-and-children-2012. Accessed 18 May 2017

United Nations (2000) Millenium Declaration. http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm. Accessed 12 July 2017

United Nations Development Programme (2016) Human Development Report 2015. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2017

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2017) 17 Goals to Transform our World. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. Accessed 18 Apr 2017

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L et al (2013) Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 381:1405–1416. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6

Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM et al (2014) Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384:957–979. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9

WHO EMRO (2013) Saving the lives of mothers and children: rising to the challenge. Background document for the High Level Meeting on Saving the Lives of Mothers and Children: Accelerating Progress Towards Achieving MDGs 4 and 5 in the Region, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

WHO EMRO (2015) Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a Health Perspective. http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/eha/documents/migrants_refugees_position_paper.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 12 July 2017

You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S et al (2015) Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet 386:2275–2286. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8

GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Neonatal, Infant, and Under-5 Mortality Collaborators:

Ali H. Mokdad, PhD (corresponding author), Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Ibrahim Khalil, MD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Michael Collison, BS, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Charbel El Bcheraoui, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Raghid Charara, MD, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon. Maziar Moradi-Lakeh, MD, Department of Community Medicine, Preventive Medicine and Public Health Research Center, Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease Research Center (GILDRC), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Ashkan Afshin, MD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Kristopher J. Krohn, BA, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Farah Daoud, BA/BS, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Adrienne Chew, ND, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Nicholas J. Kassebaum, MD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States; Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington, United States. Danny Colombara, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Leslie Cornaby, BS, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Rebecca Ehrenkranz, MPH, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Kyle J. Foreman, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States; Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom. Maya Fraser, BA, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Joseph Frostad, MPH, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Laura Kemmer, PhD, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Xie Rachel Kulikoff, BA, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Michael Kutz, BS, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Hmwe H. Kyu, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Patrick Liu, BA, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Joseph Mikesell, BS, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Grant Nguyen, MPH, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Puja C. Rao, MPH, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Naris Silpakit, BS, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Amber Sligar, MPH, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Alison Smith, BA, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Jeffrey D. Stanaway, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Johan Ärnlöv, PhD, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Division of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; School of Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden. Kalkidan Hassen Abate, MS, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia. Aliasghar Ahmad Kiadaliri, PhD, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopedics, Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. Khurshid Alam, PhD, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Deena Alasfoor, MSc, Ministry of Health, Al Khuwair, Muscat, Oman. Raghib Ali, MSc, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. Reza Alizadeh-Navaei, PhD, Gastrointestinal Cancer Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Mazandaran, Iran. Rajaa Al-Raddadi, PhD, Joint Program of Family and Community Medicine, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Khalid A. Altirkawi, MD, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Nelson Alvis-Guzman, PhD, Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. Nahla Anber, PhD, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt. Hossein Ansari, PhD, Health Promotion Research Center, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran. Carl Abelardo T. Antonio, MD, Department of Health Policy and Administration, College of Public Health, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines. Palwasha Anwari, MD, Self-employed, Kabul, Afghanistan. Al Artaman, PhD, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Hamid Asayesh, PhD, Department of Medical Emergency, School of Paramedic, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. Solomon Weldegebreal Asgedom, PhD, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia. Peter Azzopardi, PhD, Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Wardliparingga Aboriginal Research Unit, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia; Centre for International Health, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Umar Bacha, PhD, School of Health Sciences, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Aleksandra Barac, PhD, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia. Suzanne L. Barker-Collo, PhD, School of Psychology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. Neeraj Bedi, MD, College of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Ettore Beghi, MD, IRCCS - Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milan, Italy. Derrick A. Bennett, PhD, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, PhD, Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan; Centre for Global Child Health, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada. Donal Bisanzio, PhD, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. Carlos A. Castañeda-Orjuela, MSc, Colombian National Health Observatory, Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogota, Colombia; Epidemiology and Public Health Evaluation Group, Public Health Department, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia. Ruben Estanislao Castro, PhD, Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile. Hadi Danawi, PhD, Walden University, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. Kebede Deribe, MPH, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, United Kingdom; School of Public Health, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Amare Deribew, PhD, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya. Don C. Des Jarlais, PhD, Mount Sinai Beth Israel, New York, New York, United States; Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, United States. Gabrielle A. deVeber, MD, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Subhojit Dey, PhD, Indian Institute of Public Health-Delhi, Public Health Foundation of India, Gurgaon, Haryana, India. Samath D. Dharmaratne, MD, Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. Shirin Djalalinia, PhD, Undersecretary for Research & Technology, Ministry of Health & Medical Education, Tehran, Iran. Huyen Phuc Do, MSc, Institute for Global Health Innovations, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam. Alireza Esteghamati, MD, Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Maryam S. Farvid, PhD, Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, MA, United States; Harvard/MGH Center on Genomics, Vulnerable Populations, and Health Disparities, Mongan Institute for Health Policy, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States. Seyed-Mohammad Fereshtehnejad, PhD, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society (NVS), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Florian Fischer, PhD, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany. Tsegaye Tewelde Gebrehiwot, MPH, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia. Giorgia Giussani, BiolD, IRCCS - Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milan, Italy. Philimon N. Gona, PhD, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Nima Hafezi-Nejad, MD, Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Randah Ribhi Hamadeh, DPhil, Arabian Gulf University, Manama, Bahrain. Samer Hamidi, DrPH, Hamdan Bin Mohammed Smart University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Damian G. Hoy, PhD, Public Health Division, The Pacific Community, Noumea, New Caledonia. Guoqing Hu, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, China. Denny John, MPH, International Center for Research on Women, New Delhi, India. Jost B. Jonas, MD, Department of Ophthalmology, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany. Seyed M. Karimi, PhD, University of Washington Tacoma, Tacoma, Washington, United States. Amir Kasaeian, PhD, Hematology-Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; Endocrinology and Metabolism Population Sciences Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Yousef Saleh Khader, ScD, Department of Community Medicine, Public Health and Family Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan. Ejaz Ahmad Khan, MD, Health Services Academy, Islamabad, Punjab, Pakistan. Gulfaraz Khan, PhD, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, College of Medicine & Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Daniel Kim, DrPH, Department of Health Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Yun Jin Kim, PhD, Faculty of Chinese Medicine, Southern University College, Skudai, Malaysia. Yohannes Kinfu, PhD, Centre for Research and Action in Public Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. Heidi J. Larson, PhD, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Asma Abdul Latif, PhD, Department of Zoology, Lahore College for Women University, Lahore, Pakistan. Janet L. Leasher, OD, College of Optometry, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, United States. Raimundas Lunevicius, PhD, Aintree University Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust, Liverpool, United Kingdom; School of Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom. Hassan Magdy Abd El Razek, MBBCH, Mansoura Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura, Egypt. Mohammed Magdy Abd El Razek, MBBCH, Aswan University Hospital, Aswan Faculty of Medicine, Aswan, Egypt. Azeem Majeed, MD, Department of Primary Care & Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom. Reza Malekzadeh, MD, Digestive Diseases Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Ziad A. Memish, MD, Saudi Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Walter Mendoza, MD, United Nations Population Fund, Lima, Peru. Haftay Berhane Mezgebe, MS, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia. Ted R. Miller, PhD, Pacific Institute for Research & Evaluation, Calverton, MD, United States; Centre for Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia. Lorenzo Monasta, DSc, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste, Italy. Quyen Le Nguyen, MD, Institute for Global Health Innovations, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam. Carla Makhlouf Obermeyer, DSc, Center for Research on Population and Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon. Alberto Ortiz, PhD, IIS-Fundacion Jimenez Diaz-UAM, Madrid, Spain. Christina Papachristou, PhD, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Germany. Eun-Kee Park, PhD, Department of Medical Humanities and Social Medicine, College of Medicine, Kosin University, Busan, South Korea. Claudia C. Pereira, PhD, Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Max Petzold, PhD, Health Metrics Unit, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. David M. Pereira, PhD, REQUIMTE/LAQV, Laboratório de Farmacognosia, Departamento de Química, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal. Michael Robert Phillips, MD, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China; Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Farshad Pourmalek, PhD, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Mostafa Qorbani, PhD, Non-communicable Diseases Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran. Anwar Rafay, MS, Contech International Health Consultants, Lahore, Pakistan; Contech School of Public Health, Lahore, Pakistan. Vafa Rahimi-Movaghar, MD, Sina Trauma and Surgery Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Rajesh Kumar Rai, MPH, Society for Health and Demographic Surveillance, Suri, India. Saleem M. Rana, PhD, Contech School of Public Health, Lahore, Pakistan; Contech International Health Consultants, Lahore, Pakistan. David Laith Rawaf, MD, WHO Collaborating Centre, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; North Hampshire Hospitals, Basingstroke, United Kingdom; University College London Hospitals, London, United Kingdom. Salman Rawaf, MD, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom. Andre M. N. Renzaho, PhD, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia. Satar Rezaei, PhD, School of Public Health, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. Mohammad Sadegh Rezai, MD, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Mazandaran, Iran. Luca Ronfani, PhD, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”, Trieste, Italy. Gholamreza Roshandel, PhD, Golestan Research Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Digestive Diseases Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. George Mugambage Ruhago, PhD, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Mahdi Safdarian, MD, Sina Trauma & Surgery Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Saeid Safiri, PhD, Managerial Epidemiology Research Center, Department of Public Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Maragheh University of Medical Sciences, Maragheh, Iran. Mohammad Ali Sahraian, MD, MS Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Payman Salamati, MD, Sina Trauma and Surgery Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Abdallah M. Samy, PhD, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. Juan Ramon Sanabria, MD, J Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall Univeristy, Huntington, WV, United States. Benn Sartorius, PhD, Public Health Medicine, School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa; UKZN Gastrointestinal Cancer Research Centre, South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), Durban, South Africa. David C. Schwebel, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, United States. Soraya Seedat, PhD, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa. Sadaf G. Sepanlou, PhD, Digestive Diseases Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Tesfaye Setegn, MPH, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Amira Shaheen, PhD, Department of Public Health, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine. Masood Ali Shaikh, MD, Independent Consultant, Karachi, Pakistan. Morteza Shamsizadeh, MPH, Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran. Rahman Shiri, PhD, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Work Organizations, Work Disability Program, Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. Vegard Skirbekk, PhD, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway; Columbia University, New York, United States. Badr H. A. Sobaih, MD, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Chandrashekhar T. Sreeramareddy, MD, Department of Community Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Vasiliki Stathopoulou, PhD, Attikon University Hospital, Athens, Greece. Rizwan Suliankatchi Abdulkader, MD, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Arash Tehrani-Banihashemi, PhD, Preventive Medicine and Public Health Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Mohamad-Hani Temsah, MD, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. S. Thakur, MD, School of Public Health, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. Alan J Thomson, PhD, Adaptive Knowledge Management, Victoria, BC, Canada. Bach Xuan Tran, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States; Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam. Thomas Truelsen, DMSc, Department of Neurology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Kingsley Nnanna Ukwaja, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Federal Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Nigeria. Olalekan A. Uthman, PhD, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom. Tommi Vasankari, PhD, UKK Institute for Health Promotion Research, Tampere, Finland. Vasiliy Victorovich Vlassov, MD, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia. Elisabete Weiderpass, PhD, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of Research, Cancer Registry of Norway, Institute of Population-Based Cancer Research, Oslo, Norway; Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Troms, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway; Genetic Epidemiology Group, Folkhälsan Research Center, Helsinki, Finland. Robert G. Weintraub, MBBS, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Andrea Werdecker, PhD, Competence Center Mortality-Follow-Up of the German National Cohort, Federal Institute for Population Research, Wiesbaden, Germany. Mohsen Yaghoubi, MSc, School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. Mehdi Yaseri, PhD, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Terhan, Iran; Ophthalmic Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Naohiro Yonemoto, MPH, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan. Mustafa Z. Younis, DrPH, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, United States. Chuanhua Yu, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China; Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China. Aisha O. Jumaan, PhD, Independent Consultant, Seattle, Washington, United States. Theo Vos, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Simon I. Hay, DSc, Oxford Big Data Institute, Li Ka Shing Centre for Health Information and Discovery, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Mohsen Naghavi, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Haidong Wang, PhD, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States. Christopher J. L. Murray, DPhil, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Ethics declarations

This manuscript reflects original work that has not previously been published in whole or in part and is not under consideration elsewhere. All authors have read the manuscript and have agreed that the work is ready for submission and accept responsibility for its contents.The authors of this paper have complied with all ethical standards and do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose at the time of submission. The funding source played no role in the design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data, and the writing of the paper. The study did not involve human participants and/or animals; therefore, no informed consent was needed.

Funding

This research was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest at this time.

Additional information

This article is part of the supplement “The state of health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990–2015”.

The members of GBD (Global Burden of Disease) 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Neonatal, Infant, and under-5 Mortality Collaborators are listed at the end of the article. Ali H. Mokdad, on behalf of GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Neonatal, Infant, and under-5 Mortality Collaborators, is the corresponding author.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Neonatal, Infant, and under-5 Mortality Collaborators. Neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality and morbidity burden in the Eastern Mediterranean region: findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health 63 (Suppl 1), 63–77 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-0998-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-0998-x