Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine whether people who have been hospitalised as the result of non-fatal self-harm form meaningful groups based on mechanism of injury, and demographic and mental health-related factors.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of 18,103 hospital admissions for self-harm in Victoria, Australia over the 3-year period 2014/2015–2016/2017 recorded on the Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset (VAED). The VAED records all hospital admissions in public and private hospitals in Victoria. The primary analysis used a two-step method of cluster analysis. Initial analysis determined two distinct groups, one composed of individuals who had a recorded mental illness diagnosis and one composed of individuals with no recorded mental illness diagnosis. Subsequent cluster analysis identified four subgroups within each of the initial two groups.

Results

Within the diagnosed mental illness subgroups, each subgroup was characterised by a particular mental disorder or a combination of disorders. Within the no diagnosis of mental illness groups, the youngest group was also the most homogenous (all females who self-poisoned), the oldest group had a high proportion of rural/regional residents, the group with the highest proportion of males also had the highest proportion of people who used cutting as the method of self-harm, and the group with the highest proportion of metropolitan residents also had the highest proportion of people who were married.

Conclusions

Preventative interventions need to take into account that those who are admitted to hospital for self-harm are a heterogeneous group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intentional self-harm or self-injurious behaviour includes a range of behaviours that cause direct and deliberate harm to oneself, including non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal behaviour, and suicide [1,2,3]. Intentional self-harm (herein referred to as self-harm) resulting in hospital treatment is widespread in Australia and while important in its own right, it has also been shown to increase the risk of subsequent suicide [4, 5]. Studies of self-harm based on administrative data can generate important information which can inform clinical services and public health initiatives to reduce the occurrence of self-harm [6, 7].

A comprehensive national study showed more than 20,000 Australians were admitted to hospital each year since 2000 as a result of self-harm [8] and recent research has documented the increasing burden of non-fatal self-harm and other mental health-related Emergency Department (ED) presentations and hospitalisations in Australia [9,10,11,12]. A recent Victorian study showed that self-harm ED presentation rates increased by an annual average of 3.2% among all adults over the 10-year period 2006/2007–2015/2016 [9]. Clearly, non-fatal intentional self-harm is a significant public health issue and as such there is significant government and community concern regarding the prevalence of this type of behaviour in Australia.

Studies describing the epidemiology and patterns of injury among hospital-treated self-harm cases in Australia and other Western countries have consistently found that the issue is most common among young females and the mechanism of injury is most commonly self-poisoning [8, 9, 13,14,15]. However, prevention efforts would be informed by detailed information that allows for more discrete targeting of those at risk.

To improve understanding of those at risk of self-harm, previous international research has attempted to identify whether there are typologies of people who self-harm or die by suicide with regard to demographic and mental health-related factors as well as method of injury and other psychosocial factors.

A review of previous cluster analysis research focused on people who have attempted or died by suicide [16]. Among people who attempted suicide, the review identified five consistent groups across studies. However, this previous research was conducted on very small and/or non-representative samples and focused on people who had attempted suicide not all people who are hospitalised for self-harm. In addition, it is unknown to what extent the international results can be generalised to Australia.

Identifying subgroups of people who self-harm is important to move towards a more sophisticated understanding of the causes and pathways to self-harm with the ultimate aim being to inform more targeted and effective prevention measures. Any research that can elucidate these issues is useful for prevention and intervention planning purposes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether a large, representative sample of people who have been hospitalised as the result of self-harm form meaningful clusters/groups based on mechanism of injury, and demographic and mental health-related factors.

Methods

Data source

The data source was the Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset (VAED) which records all hospital admissions in public and private hospitals in the state of Victoria, Australia (population 6.2 million in 2016). The VAED is coded to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modifications (ICD-10-AM).

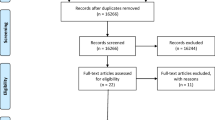

Sample selection

A review of admissions for self-harm in Victoria over the period 2014/2015–2016/2017 was conducted. Records containing a first external cause indicating self-harm (X60–X84) and a principal diagnosis that was either an injury (S00–T98) or a mental or behavioural disorder (F00–F99) were extracted. Statistical admissions and transfers within and between hospitals were excluded to reduce over counting. Deaths were excluded as the focus of this research is non-fatal self-harm. Cases among persons aged under 10 years were also excluded. Cases were identified as involving alcohol if they contained an ICD-10-AM diagnosis or external cause code referring to alcohol as detailed in previous research [17].

Data analysis

A cluster analysis was performed to determine whether hospitalised self-harm cases separate into distinct and meaningful groups. Initial analysis included the following variables:

Demographic information: sex, age at admission, marital status, indigenous status, country of birth and location of usual residence;

Mental health-related information: the presence of a mental illness diagnosis (range F00–F99) in the ICD-10-AM diagnosis codes (yes/no) and the presence or absence of the five most common mental illness diagnoses (1 mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use; 2 schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; 3 mood disorders; 4 neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; 5 disorders of adult personality and behaviour); and

Mechanism of injury.

Details including the place of occurrence of the incident and whether the incident was alcohol-related were analysed subsequently but not included in determining the clusters.

The primary analysis used a two-step method of cluster analysis. Cluster distance was determined using the log-likelihood measure within IBM SPSS Statistics (V.22) and the number of clusters was determined automatically using the Bayesian information criterion. The average silhouette measure of cohesion and separation was used to indicate overall goodness of fit by providing a measure of the degree to which identified clusters were distinct. A generally accepted criterion is that if the silhouette measure is < 0.2, then the quality of the average silhouette measure across the whole sample is considered poor, between 0.2 and 0.5 indicates a fair solution and > 0.5 is a good solution [18]. The silhouette measure of cohesion and separation provided a measure of the degree to which identified clusters are distinct. This initial analysis separated cases into two distinct groups so additional cluster analyses using the same method were conducted on the two groups individually.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services.

Results

Sample

The sample comprised 18,103 hospital admissions for self-harm in Victoria over the 3-year period 2014/2015–2016/2017. Self-harm accounted for 4.7% of injury admissions (excluding medical injury and complications of surgical care) among persons aged 10 years and older over the study period.

More than two-thirds of cases were female (67.6%), 62.4% had never been married, 72.1% lived in Melbourne metropolitan area, and the median age was 32 years (mean 35.0 years) (Table 1). A diagnosis of mental illness was recorded in 67.1% of all admissions (n = 12,142), most commonly a mood disorder (41.7% of all admissions). Disorders related to psychoactive substance use (15.7%), neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (15.5%), and disorders of adult personality and behaviour (13.8%) were also common (Table 2).

Cluster analysis

The initial analysis determined two distinct clusters/groups (average silhouette measure of 0.3) and the main predictors of group membership were related to mental illness diagnosis: the presence of any mental illness diagnosis (yes/no); and whether the patient had either a mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use, a mood disorder, a neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorder or a disorder of adult personality and behaviour. Cluster/group A will be referred to herein as the diagnosed mental illness group considering that all admissions in this cluster had a recorded mental illness diagnosis (n = 12,142). Conversely, all cases in Cluster B (the no diagnosis of mental illness group) had no recorded mental illness diagnosis (n = 5961). When cluster analysis was re-run separately on the two groups, four subgroups were identified within each of the initial groups. The main predictors of group membership within the diagnosed mental illness group were whether the patient had each of the five different categories of most common mental illnesses (see methods section). The main predictors of group membership within the no diagnosis of mental illness group were age, region of birth and marital status. Tables 1, 2 and 3 show results for the final eight groups identified.

Diagnosed mental illness subgroups

Group A1

Group A1 was characterised by being the largest of all groups (n=4884 cases), and by all cases having a diagnosis of a mood disorder (100.0%). This group had the highest proportion of cases within the diagnosed mental illness group that were currently married (30.3%), and that used poisoning by pharmaceuticals as the mechanism of injury (82.0%). More than 70% of cases were female (70.6%) and the median age at time of admission was 35 years.

Group A2

The main characteristics of group A2 were that 60.3% of cases had a neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorder and 31.6% had schizophrenia, or a schizotypal and delusional disorder. Sixty-two percent of cases were female, and more than one-third were aged 10–24 years (37.5%). Poisoning by pharmaceuticals was the most common mechanism of injury in this group (68.8%). A comparatively high proportion of self-harm incidents in this group occurred in health service areas (11.3%).

Group A3

Within the diagnosed mental illness subgroups, Group A3 had the highest proportion of cases that were male (48.5%) indigenous (2.8%) and aged 40 years or older (48.7%, median age 39 years). The main characteristics of this group were that 100% of cases had a substance use disorder, 45.2% had a mood disorder, and 72.6% of cases met the criteria for an alcohol-related admission. Poisoning by pharmaceuticals was the most common mechanism of injury in this group (64.3%).

Group A4

Within the diagnosed mental illness subgroups, Group A4 had the highest proportion of female cases (89.0%), highest proportion of residents of Metropolitan Melbourne (80.5%) and was the youngest (median age 27 years; 41.7% of cases were aged less than 25 years). More than two-thirds of this group had never been married (70.8%) and 91.0% were Australian born. All the cases had a disorder of adult personality and behaviour (100.0%), 38.9% had a mood disorder, and 21.5% a neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorder. Poisoning by pharmaceuticals was the most common mechanism of injury in this group (63.7%), however, almost a quarter of cases were the result of cutting with a sharp object (24.0%). This group had the highest proportion of self-harm incidents that occurred in health service areas (13.4%).

No diagnosis of mental illness subgroups

Group B1

Group B1 was a very homogenous group, 100% were female, never married, not indigenous, and used poisoning by pharmaceuticals as the mechanism of injury. This group was also the youngest of all groups (median age 19 years; 72.2% aged under 25 years) and almost exclusively Australian born (99.7%).

Group B2

Group B2 was characterised by being the oldest of all groups (median age 41 years; 53.2% of cases were aged 40 years or older), and having the highest proportion of cases that were widowed/divorced/separated (30.5%), residents of regional/rural Victoria (46.9%) and indigenous (9.4%). Approximately two-thirds of cases were female (64.9%) and the mechanism of injury was most commonly poisoning by pharmaceuticals (82.0%). Within the no diagnosis of mental illness groups, this group had the highest proportion of alcohol-related admissions (20.1%).

Group B3

Group B3 was characterised by being young (median age 25 years; 48.3% of cases were aged less than 25 years), never married (97.3%), Australian born (98.4%). In contrast to all other groups, males outnumbered females in this group (60.1%). Within the non-mental illness groups, this subgroup had the lowest proportion of cases that used poisoning by pharmaceuticals as the mechanism of injury (66.0%) and the highest that used cutting by sharp object (18.7%).

Group B4

Group B4 was characterised by a high proportion of cases being female (71.6%), residents of Metropolitan Melbourne (95.6%) and currently married (60.3%). In contrast to all other groups, less than one-third of these cases were Australian born (31.4%). The mechanism of injury was most commonly poisoning by pharmaceuticals (88.5%) and the median age was 37 years.

Discussion

Over the period 2014/2015–2016/2017, there were 18,103 hospital admissions in Victoria for self-harm among people aged 10 years or older. Cluster analysis showed two distinct clusters/groups with the presence of any mental illness diagnosis being the difference between these two initial groups. When cluster analysis was re-run separately on the two groups, four subgroups were identified within each of the two initial groups.

The median age at admission was 32 years and consistent with previous research [8, 13, 14, 19,20,21], females were overrepresented, poisoning by pharmaceuticals was the leading mechanism of injury and a diagnosis of mental illness was recorded for the majority of admissions (most commonly a mood disorder). However, further cluster analysis shows that complexities associated with self-harm and potential opportunities for intervention would be missed if emphasis were to be placed only on females, self-poisoning and mood disorders.

It is well established that males account for approximately three-quarters of suicide in Australia [19]. Although females accounted for two-thirds of all non-fatal self-harm admissions, males accounted for almost 6000 admissions over the study period, accounting for between 10.7 and 60.1% of cases in seven of the eight identified subgroups. Clearly, like suicide, non-fatal self-harm is a problem among males as well as females.

Although poisoning accounted for the majority of admissions within all subgroups, in four subgroups cutting with a sharp object accounted for between 18 and 24% of admissions. Considering several studies have highlighted the significance of this method of self-harm, showing that cutting is a strong predictor of repetition of self-harm [22] and future suicide [5]—it should be a target for prevention efforts.

Finally, although mood disorders were common across all diagnosed mental illness subgroups, these subgroups did have different profiles with regard to the conditions represented. All people in A1 had a mood disorder, all in A3 had a substance use disorder, and all in A4 had a disorder of adult personality. Group A2 was less homogenous; neurotic and stress-related and somatoform disorders were common as were schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders. These results suggest that among people who have a diagnosed mental illness and who self-harm, individuals have a range of illnesses and that mood disorders, while common, are not present among all in this population.

Aside from the mental illness-related information, there were clear differences between some groups based on demographic and other factors such as method of self-harm and whether the incident was alcohol-related. For example, within the diagnosed mental illness groups, A1 has the highest proportion of poisoning cases, A3 had the highest proportion of males and alcohol-related incidents, and A4 had the highest proportion of females and those who used cutting as the method of self harm. With regard to the no diagnosis of mental illness groups, the youngest group (B1) was also the most homogenous (all female, never married and used poisoning by pharmaceuticals as the method of self harm), B2 was the oldest and had a high proportion of rural/regional residents, B3 had the highest proportion of males and the highest proportion of people who used cutting as the method of self-harm, and B4 had the highest proportion of metropolitan residents and those currently married.

A review of previous cluster analysis studies focused on people who had attempted suicide [16] identified five consistent groups, four of which were in some way consistent with the groups in the current study. The review identified a group of people with comorbid mental illness—which was a feature of groups A2, A3 and A4 in the current study. A group of people with personality disorders and substance abuse was also identified—consistent with group A3, and a group of people with depression was identified—consistent with group A1. Finally, a group without mental illness was also identified, consistent with groups B1–B4 in the current study.

Importantly, the data presented in this paper include all admissions where hospital coders determined that the injury or poisoning was purposely self-inflicted; therefore, incidents where the person had the intent to die by suicide (but did not die) are included, but self-harm cases without suicidal intent are also included. Although it is common for research studies to combine these behaviours, research suggests that they differ in clinically relevant ways, including on the basis of intention, frequency, and lethality [23, 24]. Therefore, it could be that some of the clusters identified in this study are more related to suicide attempts and some are more related to non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). This point is further reinforced by the fact that some subgroups identified in this study are consistent with groups that are currently identified in Australia as priority populations in policy due to the evidence base regarding which groups of people have higher rates of suicide, for example, young, unmarried males, without diagnosed mental illness or older regional/rural residents who are widowed/divorced/separated. To inform suicide prevention initiatives, future research should include linkage of hospital admissions data to death data to determine which cluster(s) may be at increased risk of suicide following self-harm-related admission. In addition, this type of linkage research may show that some clusters are not associated with suicide and, therefore, intervention and prevention efforts may be able to be tailored specifically for the population who engage in non-fatal self-harm.

Limitations

This research has some limitations. The numbers reported could be an underestimate of actual hospitalisations for self-harm, due to known issues with administrative data, particularly in relation to capturing self-harm [25]. In addition, the dataset used for this analysis is episode- and not person-based meaning the same person could be represented more than once. The study also lacks a population-based control group—it may be that certain variables cluster together in the population and this is why they cluster in the current analysis. Finally, the analysis was restricted to available administrative data items and, therefore, other information that would potentially help characterise the groups, such as the presence or absence of intent to die by suicide, exposure to potential stressors, etc., was not able to be included.

Conclusion

Despite the inherent limitations of administrative data, this study demonstrates that if interrogated in a novel way, administrative data can be used to identify meaningful priority groups to inform suicide and self-harm prevention planning and policy.

These results show that although young females who deliberately poison themselves are clearly an important population to target with preventative interventions, there is a need to look beyond this population—those who are admitted to hospital for self-harm are a heterogeneous group.

References

Nock MK, Joiner TE Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ (2006) Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res 144(1):65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010

Nock MK (2010) Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:339–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258

Skegg K (2005) Self-harm. Lancet 366:1471–1483

Reith DM, Whyte IM, Carter G, McPherson M, Carter N (2004) Risk factors for suicide and other deaths following hospital treated self-poisoning in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 38:520–525

Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, Lawlor M, Guthrie E, Mackway-Jones K, Appleby L (2005) Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 162:297–303

Windfuhr K, Kapur N (2011) International perspectives on the epidemiology and aetiology of suicide and self-harm. In: O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J (eds) International handbook of suicide prevention: research, policy and practice. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, UK, pp 27–57

Arensman E, Corcoran P, Fitzgerald AP (2011) Deliberate self-harm: extent of the problem and prediction of repetition. In: O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J (eds) International handbook of suicide prevention: research, policy and practice. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, UK, pp 119–131

Harrison JE, Henley G (2014) Suicide and hospitalised self-harm in Australia: trends and analysis. Injury research and statistics, 93, Cat. no. INJCAT 169. AIHW, Canberra

Clapperton A (2017) Non-fatal hospital-treated intentional self-harm injury. Hazard, 83 edn. Monash University Accident Research Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Hiscock H, Neely RJ, Lei S, Freed G (2018) Paediatric mental and physical health presentations to emergency departments, Victoria, 2008–15. Med J Aust 208(8):343–348

Leckning BA, Li SQ, Cunningham T, Guthridge S, Robinson G, Nagel T, Silburn S (2016) Trends in hospital admissions involving suicidal behaviour in the Northern Territory, 2001–2013. Australas Psychiatry 24(3):300–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856216629838

Perera J, Wand T, Bein KJ, Chalkley D, Ivers R, Steinbeck KS, Shields R, Dinh MM (2018) Presentations to NSW emergency departments with self-harm, suicidal ideation, or intentional poisoning, 2010–2014. Med J Aust 208(8):348–353

Hawton K, Fagg J, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A (1997) Trends in deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1985–1995. Implications for clinical services and the prevention of suicide. Br J Psychiatry 171:556–560. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.171.6.556

Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, Cooper J, Kapur N (2010) Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England: 2000–2007. Br J Psychiatry 197(6):493–498. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077651

Geulayov G, Kapur N, Turnbull P, Clements C, Waters K, Ness J, Townsend E, Hawton K (2016) Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000–2012: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. BMJ Open 6(4):e010538. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010538

Wołodźko T, Kokoszka A (2014) Classification of persons attempting suicide. A review of cluster analysis research. Psychiatr Pol 48(4):823–834

McKenzie K, Harrison JE, McClure RJ (2010) Identification of alcohol involvement in injury-related hospitalisations using routine data compared to medical record review. Aust N Z J Public Health 34(2):146–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00499.x

Mooi E, Sarstedt M (2011) A concise guide to market research: the process, data, and methods using IBM SPSS statistics. Springer, Berlin

Elnour A, Harrison J (2007) Lethality of suicide methods. Inj Prev 14:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2007.016246

Haw C, Hawton K, Houston K, Townsend E (2001) Psychiatric and personality disorders in deliberate self-harm patients. Br J Psychiatry 178:48–54

Lilley R, Owens D, Horrocks J, House A, Noble R, Bergen H, Hawton K, Casey D, Simkin S, Murphy E, Cooper J, Kapur N (2008) Hospital care and repetition following self-harm: multicentre comparison of self-poisoning and self-injury. Br J Psychiatry 192(6):440–445. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043380

Griffin E, Arensman E, Dillon CB, Corcoran P, Williamson E, Perry IJ (2016) National self-harm registry Ireland annual report 2015. National Suicide Research Foundation, Cork

Guertin T, Lloyd-Richardson E, Spirito A, Donaldson D, Boergers J (2001) Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents who attempt suicide by overdose. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(9):1062–1069

Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM (2007) Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Arch Suicide Res Off J Int Acad Suicide Res 11(1):69–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110600992902

Stanley B, Currier GW, Chesin M, Chaudhury S, Jager-Hyman S, Gafalvy H, Brown GK (2017) Suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury in emergency departments underestimated by administrative claims data. Crisis 1:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000499

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Clapperton, A.J. Identifying typologies among persons admitted to hospital for non-fatal intentional self-harm in Victoria, Australia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 1497–1504 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01747-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01747-1