Abstract

Purpose

To assess the quality of the research about how employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young workers, and to summarize the available evidence.

Methods

We undertook a systematic search of three databases using a tiered search strategy. Studies were included if they: (a) assessed employment conditions such as working hours, precarious employment, contract type, insecurity, and flexible work, or psychosocial workplace exposures such as violence, harassment and bullying, social support, job demand and control, effort-reward imbalance, and organizational justice; (b) included a validated mental health measure; and (c) presented results specific to young people aged ≤ 30 years or were stratified by age group to provide an estimate for young people aged ≤ 30 years. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Exposures (ROBINS-E) tool.

Results

Nine studies were included in the review. Four were related to employment conditions, capturing contract type and working hours. Five studies captured concepts relevant to psychosocial workplace exposures including workplace sexual harassment, psychosocial job quality, work stressors, and job control. The quality of the included studies was generally low, with six of the nine at serious risk of bias. Three studies at moderate risk of bias were included in the qualitative synthesis, and results of these showed contemporaneous exposure to sexual harassment and poor psychosocial job quality was associated with poorer mental health outcomes among young workers. Longitudinal evidence showed that exposure to low job control was associated with incident depression diagnosis among young workers.

Conclusions

The findings of this review illustrate that even better studies are at moderate risk of bias. Addressing issues related to confounding, selection of participants, measurement of exposures and outcomes, and missing data will improve the quality of future research in this area and lead to a clearer understanding of how employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young people. Generating high-quality evidence is particularly critical given the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on young people’s employment. In preparing for a post-pandemic world where poor-quality employment conditions and exposure to psychosocial workplace exposures may become more prevalent, rigorous research must exist to inform policy to protect the mental health of young workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Employment is a key social determinant of health [1, 2] and has wide-reaching consequences on employees’ physical [3] and mental health [4, 5]. Because the conditions in which people work are socially structured, individuals who have the least power and fewest political, economic, social, and cultural resources are likely to experience greater exposure to poorer working environments and unemployment [6]. Young people are one such group, and many may face a conflation of disadvantages related to employment that lead to social exclusion as they transition from education to work [7]. This has been exacerbated in the current climate of COVID-19 economic repercussions, as industries in which young people are concentrated, such as tourism and hospitality, have been disproportionately affected by job losses, hours reductions, and uncertain business futures [8,9,10,11]. Recovery in these sectors is anticipated to be slow, leading to continued unemployment and underemployment among young people, as well as greater competition for the jobs that do exist, potentially eroding employment conditions and increasing exposure to psychosocial workplace exposures.

The process of transitioning from education to the labour force for young people has become increasingly longer and more difficult globally [12], and this will likely be intensified by COVID-19. In addition to rising unemployment rates among young people, the quality of employment for young people is a significant concern: young people are more likely to work in poor-quality, insecure, and unstable jobs with low wages, and permanent positions are rare [13, 14]. This is troubling, as workers in jobs characterized by these conditions are more vulnerable to psychosocial workplace exposures such as bullying [15], and individuals in lower status jobs may be more likely to experience greater job demand and reduced control [16].

The age at which people transition from education to work is also commonly associated with the first onset of mental illness. Approximately half of lifetime mental disorders start by the mid-teens, and 75% start by the mid-twenties [17]. In countries such as Australia, people aged 16–25 years have the highest prevalence of mental illness compared to all other age groups [18]. It is therefore critically important to consider the sensitivity of this time period for young people’s mental health in the context of the work experiences they are encountering, as poorer employment conditions and exposure to psychosocial workplace exposures, such as that marked by poor psychosocial working environments [19], increased job strain [20], effort-reward imbalance [21], lack of organizational justice [22], low social support [23], and job insecurity [24] are associated with poorer mental health in the general population.

While the associations between poorer employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures and mental health have been frequently asserted in the literature [19, 20, 23,24,25], a paucity of research has focused on people aged 30 years and under as they transition into the labour force. The existing scoping review [26] highlighted the importance of exploring how precarious employment affects the health of young workers, but is not systematic and therefore does not collate and evaluate the quality of all relevant evidence. The previous systematic review [27] in this area was broad in scope, leading to heterogenous outcome measures which may obfuscate the true relationship between exposures and outcomes. This review placed little emphasis on quality assessment results, and provided scant discussion of how flaws in included studies may impact their results, and therefore their policy and practice relevance. This raises significant concerns about the risk of bias in available evidence and its implications for interpreting and applying study results. Considering the substantial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people’s employment, accurately understanding how employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young people is more important than ever before. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to focus specifically on young people as they are entering and establishing themselves in the workforce, and to assess how employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact mental health. We use a rigorous Risk of Bias tool to assess the quality of the literature and provide considerations for improving the quality of future research.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

For this systematic review, we searched Scopus, PsycINFO, and Pubmed from their inception to 22 January 2021. We used a three-tiered search strategy to identify studies including terms relating to mental health, employment, and young people. We then applied an additional fourth tier relevant to employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures. See Appendix 1 for the search terms used for each tier and for information on how they were combined. No restrictions were placed on language or publication type. This systematic review is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020151406). We note that since registration with PROSPERO, the review has been modified in response to reviewers’ comments.

Studies were included if they assessed the effect of employment conditions or psychosocial workplace exposures on mental health for people aged ≤ 30 years. We were purposefully broad with our conceptualization of employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures. This is because some concepts, such as precarious employment [28], are discussed and assessed in myriad ways in the literature and may not be conceived of uniformly. In particular, exposures of interest included employment conditions such as working hours, notions of precarious employment, contract type, insecurity, and flexible work. With regards to psychosocial workplace exposures, we were interested in violence, harassment, and bullying, social support, job demand and control, effort-reward imbalance, and organizational justice. Measures of job quality which included components of employment conditions and/or psychosocial workplace exposures were eligible for inclusion. We were deliberately inclusive with the measurement of exposures, as we anticipated that most exposures would be measured through self-report and without using validated tools. Studies which included individuals of working age (15–30 years inclusive) were eligible for inclusion. We accepted studies wherein individuals experiencing the exposures of interest were compared to unexposed individuals, unemployed individuals, or individuals who were not in the labour force. We excluded physical, ergonomic, or chemical workplace exposures, as we were not interested in indirect mental health effects which would be mediated by physical health effects. Our focus was on identifying ways to improve the psychosocial working conditions and arrangements of young people.

We focused on the common mental disorders anxiety and depression as outcomes and, therefore, included any studies that either (1) used a validated mental measure of symptomology, such as depression and depressive symptoms, anxiety or anxiety symptoms, general mental health status (e.g. SF-36), or psychological distress (e.g. K6), or (2) included a mental health diagnosis or register data such as hospital admission records for a mental health condition.

We included international evidence from all countries in our review, and only considered research that was published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies with a prospective cohort, case–control, retrospective, cross-sectional, or intervention trial design were considered for inclusion, as we wanted to present all the literature identified relating to this age group, enabling comprehensiveness while acknowledging limitations. We excluded studies which were case reports, qualitative in nature, study protocols, or descriptive works only. Studies which could not be obtained in English were excluded, as were existing reviews. Where the same dataset was used in multiple studies, we included the most recent study covering the longest period.

Two reviewers (MS and AM) reviewed extracted titles and abstracts using Excel. Disagreement was resolved by including the article. Articles identified as potentially relevant were screened in full and assessed for inclusion by one reviewer (MS).

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted by one reviewer (MS) in a pre-piloted data extraction tool in Microsoft Excel. Data were extracted on study design, study sample, workplace exposure, outcome measure, method of statistical analysis, and key results.

Risk of bias was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Exposures (ROBINS-E) tool. The ROBINS-E tool is based on the ROBINS-I instrument [29]. There are three steps to applying the ROBINS-E tool, two of which are done prior to its application. First, reviewers must clarify their review question and identify considerations specific to their topic, such as potential confounders, which are important when assessing bias. Second, the authors then describe a hypothetical, ideal randomized controlled trial which would answer their review question. Finally, authors evaluate each study as compared to the ideal study across the seven risk of bias (RoB) items: (1) bias due to confounding, 2) bias in selection of participants into the study, (3) bias in classification of exposures, (4) bias due to departures from intended exposures, (5) bias due to missing data, (6) bias in measurement of outcomes, 7) bias in selection of the reported result.

RoB on each item is evaluated as ‘low’, ‘moderate’, ‘serious’, or ‘critical’, and reviewers determine both a study-level and an item-level RoB judgment. An important benefit of the ROBINS-E approach to RoB assessment is that it moves away from study-design-based judgments, such as non-randomized studies automatically receiving higher RoB than RCTs using the GRADE approach [30].

Two reviewers (MS and TK) independently evaluated the RoB of included studies. Differences were resolved by consensus, with input from a third reviewer (MJS). We used the available ROBINS-E template [31] to create a custom template with the signaling questions tailored to our review topic and ideal RCT. Studies were classified at low risk of bias if all RoB items were coded as low risk, moderate risk of bias if one or more items were coded as moderate but none as serious, serious risk of bias if at least one item was coded as serious but none as critical, and critical risk of bias if at least one item was coded as critical [32]. In line with ROBINS-I guidance which advocates caution in including studies at increased risk of bias in analyses, [32] we have included only studies at low or moderate risk of bias in the qualitative synthesis.

Key findings from the included studies were summarized in a descriptive table and discussed using a narrative/descriptive synthesis. While the aim of our study was to pool the available evidence and conduct a meta-analysis, we were unable to do this because of variation in exposure and outcome measures and because an insufficient number of studies were identified as having a low or moderate risk of bias. Our review followed PRISMA guidelines [33], see Appendix 2.

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

Results

Study characteristics

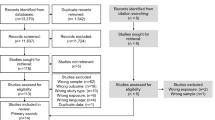

The flow of studies into the review is shown in Fig. 1. After full-text review, 27 studies were excluded. The studies and reasons for exclusion can be seen in Appendix 3. Nine studies were identified for inclusion in the systematic review and are detailed in Table 1. Of the nine studies, four were related to employment conditions, capturing contract type and working hours [34,35,36,37]. The five remaining studies captured concepts relevant to psychosocial workplace exposures including workplace sexual harassment [38, 39], psychosocial job quality [40], work stressors [41], and job control [42].

Three of the nine studies used data from the United States [38, 39, 41]. Of the remaining six, one was from France [34], one from Canada [35], one from Turkey [36], one from Egypt [37], one from Australia [40], and one from Denmark. [42] Three studies used a cross-sectional design [34, 36, 38], while the remaining six used prospective cohorts and employed a longitudinal design. [35, 37, 39,40,41,42] Descriptive information related to the studies is shown in Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment

A summary of the study-level and item-level RoB is shown in Table 2. Regarding bias due to confounding, one study was at low risk, five studies were at moderate risk and three were at serious risk. We judged two studies to be at low risk of bias due to the selection of participants, four at moderate risk, and three at serious risk. Four studies were at moderate risk of bias due to the measurement of exposure and five were at serious risk. In relation to departure from the exposure, three studies were at low risk, three were at moderate risk and for three studies, this domain was not relevant. We judged three studies at low risk of bias due to missing data, one at moderate risk, and five at serious risk. One study was at low risk of bias due to measurement of outcomes, and eight were at moderate risk. Seven studies were at low risk of bias due to the reported results, and two studies were at serious risk. Of the 9 studies, none were judged as being at low risk of bias, three [39, 40, 42] were assessed as having a moderate risk of bias, and six studies were assessed as having a serious risk of bias [34,35,36,37,38, 41]. The results that follow focus only on those studies at moderate risk of bias.

Qualitative synthesis

Of the three studies at moderate risk of bias, one assessed sexual harassment in the workplace [39], one assessed psychosocial job quality [40], and one assessed job control. [42]

Using data from the Youth Development Study and a prospective cohort design, Houle et al. [39] examined the association between workplace sexual harassment at ages 14–18, 19–26, and 29–30 years on depressive symptoms at ages 30–31 years. In fully adjusted regression models including both prior and contemporaneous sexual harassment, only contemporaneous sexual harassment at age 30–31 years was associated with increased depressive symptoms (coef 0.512, SE = 0.162), with the authors concluding that more recent measures of harassment explain the effect of previous harassment on depressive symptoms. In further sensitivity analyses, the authors did not find an interaction between gender and sexual harassment.

A study using data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics of Australia survey assessed the association between psychosocial job quality (capturing elements of job control, job demands and complexity, job insecurity, and unfair pay) and an overall measure of mental health among young people aged ≤ 30 years. Using longitudinal linear fixed-effects regression, Milner et al. [40] found that being in optimal quality employment was associated with a slight improvement in mental health within persons (coef 0.75, 95% CI 0.40, 1.10), compared to individuals who were not in the labour force (the reference group). However, there was a stepwise decrease in mental health when a young person was working in a job with 2 (coef -0.60, 95% CI -0.97, -0.23) or 3 or more psychosocial job adversities (coef -1.68, 95% CI -2.18, -1.17).

Finally, Svane-Petersen et al. [42] prospective cohort study of job control and incident main diagnosis of depressive disorder used data from individuals in the Danish Work Life Course Cohort aged 15–30 years who entered the Danish labor market between 1995 and 2009. Job control was assessed using a Job Exposure Matrix (JEM) and incident depression diagnosis was assessed using register data of in- or outpatient treatment. In Cox proportional hazards models, individuals in occupations with lower levels of past year job control had an increased risk of incident depressive disorder (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.16, 1.38) compared to individuals in occupations with higher levels of job control. In models stratified by gender, the authors found the association between past year job control and risk of incident depression was similar among men (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.19, 1.61) and women (HR 1.19, 95% CI 1.08, 1.32).

Discussion

Of the nine studies included in this review, six were at serious risk of bias and were excluded from the qualitative synthesis. The three remaining studies, all at moderate risk of bias, indicated that exposure to psychosocial workplace exposures such as sexual harassment and low job control, as well as poor psychosocial job quality, are associated with deteriorations in mental health among young workers. Taken together, these findings indicate that (1) higher-quality research suggests that exposure to psychosocial workplace exposures negatively impacts the mental health of young people and (2) further, more rigorous research is needed to assess how additional facets of employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young people.

Two of the three moderate risk of bias studies identified contemporaneous associations between workplace exposures and mental health outcomes among young people. Only one moderate quality study assessed how a workplace exposure impacted mental health outcomes over time among young people. Further, we did not identify any studies exploring what the mechanisms are that may explain these associations. In conjunction with necessary improvements identified through our application of the ROBINS-E RoB tool, the use of more advanced epidemiologic methods, such as mediation analysis, would facilitate an understanding of the mechanisms and pathways by which employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact mental health outcomes among young people [43].

Additionally, all three studies explored in the qualitative synthesis highlighted that experiencing workplace violence, poor psychosocial job quality, and low job control have negative impacts on the mental health of young people. Two of the studies identified the importance of considering additional characteristics when assessing this association, namely gender [39, 42]. This is an approach that should be adopted and expanded in further study, as characteristics such as disability status, immigrant and ethnic background, and First Nations identity may influence the relationship between working conditions and mental health outcomes among young people [26, 44,45,46]. Such research is more important than ever before, as the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that the economic repercussions of restrictions will not affect all groups equally [46]. Focusing on these associations will lead to more targeted results which may inform policies and interventions, ultimately leading to reductions in health inequalities.

Evidence from previous economic crises [47] and the current COVID-19 pandemic [10] shows that young people are being hit particularly hard by shutdowns and job losses, providing an even stronger impetus for developing a nuanced understanding of how employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young people. Policymakers, public health professionals, and society as a whole must ensure that young people not only re-enter work to ameliorate lifelong scarring effects, but are employed in jobs which benefit, or at the very least are not detrimental to mental health. Until this research base exists, we cannot have confidence that we are doing right by young people and their mental health as they engage in work and bear the economic burdens of the pandemic.

For this area of research to progress, researchers will need to address the issues raised by the application of the ROBINS-E tool. While residual and unmeasured confounding are always a concern in observational studies, this can be counteracted by the careful consideration of potential confounders at the study design stage, as well as the application of methods that minimize the risk of bias due to confounding. The use of longitudinal data will facilitate improved confounder control, particularly by allowing for baseline control of the outcome. A recent systematic review of the effects of unemployment on the mental health of young people reported that when confounders, including baseline mental health were controlled for, the effect estimates decreased and led to mixed results [48]. This indicates the importance of consistently controlling for appropriate confounders.

Additionally, greater transparency regarding study inclusion and exclusion criteria and differences between individuals who did and did not participate in studies would allow readers to better understand the internal validity of the study and interpret results appropriately. While recognizing that participant retention is a perennial challenge, comparison of the characteristics of those who have attrited compared to those retained would likewise permit readers to draw more accurate conclusions about the study’s results. Similarly, improved description and handling of missing data, such as through multiple imputation procedures would reduce the risk of bias in studies.

Finally, eight of the nine studies included in this systematic review relied on subjective, self-reported measures of the employment-related exposures and mental health outcomes. This means results may be impacted by dependent and differential misclassification of the exposure related to the outcome (e.g. people with poorer mental health may be more likely to remember or report certain aspects of their employment situation), potentially biasing results in an unknown direction. Self-reported measures of mental health are useful and important measures but could be improved upon in future studies by being paired with more objective sources of data, such as hospital admission data or prescription medication information. Using linked data may allow researchers to ‘triangulate’ their findings using a combination of subjective and objective measures of mental health to more fully understand the employment-mental health relationship. The use of objective data sources, as well as validated self-report measures of psychosocial workplace exposures and employment conditions (such as The Employment Precariousness Scale [49]) may contribute to more comparable exposures and outcomes across studies. This may also work to resolve complications in the literature arising from differing definitions and usage of terminology regarding employment-related exposures (e.g. precarious employment), in addition to challenges with measurement.

There are several limitations of this systematic review. The search strategy may have missed relevant articles, and our search may not have been sensitive to studies which were stratified by age group. In addition, this systematic review was limited to published studies in English. Finally, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis due to variations in the exposures and outcomes of the included studies.

Despite these limitations, a significant strength of this study is the extensive risk of bias assessment that we undertook. Our qualitative synthesis included only studies at moderate risk of bias, focusing only on studies with greater internal validity. As such, our study has highlighted areas for improvement in future work and has relayed results of only better-quality studies.

In conclusion, this systematic review has indicated a dearth of rigorous evidence related to the mental health impacts of employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures among young people and has found that even higher-quality studies are still at moderate risk of bias. By improving on key areas relating to bias, such as control for confounding, appropriate handling of missing data, and measurement of exposures and outcomes, researchers can contribute high-quality evidence expounding the relationship between employment conditions, psychosocial workplace exposures, and mental health, thereby informing policy to improve the health of young workers. In light of the coronavirus pandemic, such data-driven policies to protect and improve the health of young people are more important than ever before.

Availability of data and materials

All data presented in this review are available in the included papers. Details on the custom quality assessment tool and its application to single studies are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

CSDH (2008) Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. CSDH, Geneva

Dahlgren G, Whitehead M (1991) Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. WHO, Geneva

Hergenrather KC, Zeglin RJ, McGuire-Kuletz M, Rhodes SD (2015) Employment as a social determinant of health: a review of longitudinal studies exploring the relationship between employment status and mental health. Rehabil Res Policy Educ 29(3):261–290

Modini M, Joyce S, Mykletun A, Christensen H, Bryant RA, Mitchell PB et al (2016) The mental health benefits of employment: results of a systematic meta-review. Australas Psychiatry 24(4):331–336

Van Der Noordt M, IJzelenberg H, Droomers M, Proper KI (2014) Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med 71(10):730–736

Dahlgren G, Whitehead M (2006) Levelling up (part 2): a discussion paper on European strategies for tackling social inequities in health [Internet]. Geneva. http://www.who.int/entity/social_determinants/resources/leveling_up_part2.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2020

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2018) Promoting Inclusion through Social Protection: Report on the World Social Situation 2018 [Internet]. New York: United Nations, pp 1–139. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2018/06/rwss2018-full-advanced-copy.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2020

Atkins M, Callis Z, Flatau P, Kaleveld L (2020) Covid-19 and youth unemployment [Internet]. https://www.csi.edu.au/media/uploads/csi_fact_sheet_social_covid-19_youth_unemployment.pdf. Accessed 2 Sep 2020

IBISWorld (2020) COVID-19 economic assessment [Internet]. https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-insider/media/5488/covid-19-special-report-18-aug.pdf. Accessed 2 Sep 2020

Coates B, Cowgill M, Chen T, Mackey W (2020) Shutdown: estimating the COVID-19 employment shock [Internet]. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Shutdown-estimating-the-COVID-19-employment-shock-Grattan-Institute.pdf. Accessed 12 Jun 2020

OECD (2020) OECD Unemployment rates news release : record rise in OECD unemployment rate in April 2020 [Internet]. https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/unemployment-rates-oecd-update-june-2020.htm. Accessed 27 Aug 2020

Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB et al (2016) Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 387(10036):2423–2478

International Labour Office (2017) Global employment trends for youth 2017: paths to a better working future. International Labour Office, Geneva

International Labour Office (2016) Non-standard employment around the world: understanding challenges, shaping prospects. ILO, Geneva

Feijó FR, Gräf DD, Pearce N, Fassa AG (2019) Risk factors for workplace bullying: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(11):1945

Bonsaksen T, Thørrisen MM, Skogen JC, Aas RW (2019) Who reported having a high-strain job, low-strain job, active job and passive job? The WIRUS screening study. PLoS ONE 14(12):1–13

Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Üstün TB (2007) Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20(4):359–364

Productivity Commission. Mental Health, Draft Report. Canberra; 2019

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bruinvels D, Frings-Dresen M (2010) Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup Med (Lond) 60(4):277–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqq081

Madsen IEH, Nyberg ST, Magnusson Hanson LL, Ferrie JE, Ahola K, Alfredsson L et al (2017) Job strain as a risk factor for clinical depression: systematic review and meta-analysis with additional individual participant data. Psychol Med 47(8):1342–1356

Rugulies R, Aust B, Madsen IEH (2017) Effort–reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 43(4):294–306

Ndjaboue R, Brisson C, Vezina M (2012) Organisational justice and mental health: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med 69:694–700

Harvey S, Modini M, Joyce S, Milligan-Saville J, Tan L, Mykletun A et al (2017) Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med 74(4):301–310

Rönnblad T, Grönholm E, Jonsson J, Koranyi I, Orellana C, Kreshpaj B et al (2019) Precarious employment and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 45(5):429–443

Kim TJ, Von Dem Knesebeck O (2015) Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? A systematic review of studies investigating the health-related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health 15(1):1–10

Vancea M, Utzet M (2017) How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: a scoping study on social determinants. Scand J Public Health 45(1):73–84

Law PCF, Too LS, Butterworth P, Witt K, Reavley N, Milner AJ (2020) A systematic review on the effect of work-related stressors on mental health of young workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 93(5):611–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01516-7

Kreshpaj B, Orellana C, Burström B, Davis L, Hemmingsson T, Johansson G et al (2020) What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scand J Work Environ Heal 46(3):235–247

Morgan RL, Thayer KA, Santesso N, Holloway AC, Blain R, Eftim SE et al (2019) A risk of bias instrument for non-randomized studies of exposures: A users’ guide to its application in the context of GRADE. Environ Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.004

Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, Mustafa RA, Meerpohl JJ, Thayer K et al (2019) GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 111:105–114

The ROBINS-E tool (Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies- of Exposures) (2021). https://www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/centres/cresyda/barr/riskofbias/robins-e/. Accessed 11 Feb 2020

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:4–10

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700

Blanquet M, Labbe-Lobertreau E, Sass C, Berger D, Gerbaud L (2017) Occupational status as a determinant of mental health inequities in French young people: Is fairness needed? Results of a cross-sectional multicentre observational survey. Int J Equity Health 16(1):1–11

Domene JF, Arim RG, Law DM (2017) Change in depression symptoms through emerging adulthood: disentangling the roles of different employment characteristics. Emerg Adulthood 5(6):406–416

Kiran S, Unal A, Ayoglu F, Konuk N, Ocakci A, Erdogan A (2007) Effect of working hours on behavioral problems in adolescents: a Turkish sample. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 14:103–110

Sharaf MF, Rashad AS (2020) Does precarious employment ruin youth health and marriage? Evidence from Egypt using longitudinal data. Int J Dev Issues 19(3):391–406

Fineran S, Gruber JE (2009) Youth at work: adolescent employment and sexual harassment. Child Abus Negl 33(8):550–559

Houle JN, Staff J, Mortimer JT, Uggen C, Blackstone A (2011) The impact of sexual harassment on depressive symptoms during the early occupational career. Soc Ment Health 1(2):89–105

Milner A, Krnjacki L, LaMontagne AD (2017) Psychosocial job quality and mental health among young workers: a fixed-effects regression analysis using 13 waves of annual data. Scand J Work Environ Heal 43(1):50–58

Mortimer JT, Staff J (2004) Early work as a source of developmental discontinuity during the transition to adulthood. Dev Psychopathol 16(4):1047–1070

Svane-Petersen AC, Holm A, Burr H, Framke E, Melchior M, Rod NH et al (2020) Psychosocial working conditions and depressive disorder: disentangling effects of job control from socioeconomic status using a life-course approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55(2):217–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01769-9

VanderWeele TJ (2015) Explanation in causal inference: methods for mediation and interaction. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Benach J, Vives A, Amable M, Vanroelen C, Tarafa G, Muntaner C (2014) Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health 35(1):229–253

Milner A, Krnjacki L, Butterworth P, Kavanagh A, LaMontagne AD (2015) Does disability status modify the association between psychosocial job quality and mental health? A longitudinal fixed-effects analysis. Soc Sci Med 144:104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.024

van Barneveld K, Quinlan M, Kriesler P, Junor A, Baum F, Chowdhury A et al (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic: lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ Labour Relat Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304620927107

Bettio F, Corsi M, Ippoliti CD, Lyberaki A, Lodovici M, Verashchagina A (2012) The impact of the economic crisis on the situation of women and men and on gender equality policies. CESifo DICE Report. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4a10e8f6-d6d6-417e-aef5-4b873d1a4d66. Accessed 27 Aug 2020

Bartelink VHM, Zay Ya K, Guldbrandsson K, Bremberg S (2019) Unemployment among young people and mental health: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health 48(5):544–558

Vives A, Amable M, Ferrer M, Moncada S, Llorens C, Muntaner C et al (2010) The Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES): psychometric properties of a new tool for epidemiological studies among waged and salaried workers. Occup Environ Med 67(8):548–555

Acknowledgements

We honor the memory of coauthor Associate Professor Allison Milner, whose intellect, quirk, drive and vitality will never be forgotten. We would like to acknowledge Dr Jim Berryman for his assistance with the search strategy.

Funding

MS is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship provided by the Australian Commonwealth Government. MJS is a recipient of an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (project number FT180100075) funded by the Australian Government. TK is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200100607). This research has been funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Partnership Project (APP1151843) funded by the Australian Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work (MS, AM, MJS, TK); acquisition of the data (MS, AM); analysis and interpretation of the data (MS, SD, MJS, TK); drafting the work (MS, MJS, TK); critical revision of the work (MS, SD, AK, MJS, TK); final approval of the draft for submission (MS, SD, AK, MJS, TK).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shields, M., Dimov, S., Kavanagh, A. et al. How do employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young workers? A systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 1147–1160 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02077-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02077-x