Abstract

The concept of brain death (BD) has been widely accepted by medical and lay communities in the Western world and is the basis of policies of organ retrieval for transplantation from brain-dead donors. Nevertheless, concerns still exist over various aspects of the clinical condition it refers to. They include the utilitarian origin of the concept, the substantial international variation in BD definitions and criteria, the equivalence between BD and the donor’s biological death, the practice of retrieving organs from donors who are not brain-dead (as in non-heart-beating organ donor protocols), the proposal to abandon the dead donor rule and attempts to overcome these problems by adapting rules and definitions. Suggesting that BD, as it was originally proposed by the Harvard Committee, is more a moral than a scientific concept, we argue that current criteria do not empirically justify the definition of BD; yet they consistently identify a clinical condition in which organ retrieval can be morally and socially justified. We propose to revert to the old term of “irreversible coma” or, better yet, of “irreversible apnoeic coma”, thus abandoning the presumption of diagnosing the death of all intracranial neurons and/or the patient’s biological death. On the other hand, we think that a (re)definition of the vital status of donors identified on neurological criteria can only occur through a prior (re)definition of death, a task which is not only medical but societal.

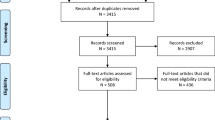

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term “brain death” (BD) encapsulates two correlated concepts: the death of the brain and the patient’s death certified by neurological criteria. In this sense, it is the basis of the current policies of organ retrieval for transplantation from brain-dead heart-beating donors. Several authors have challenged the fact that medicine can demonstrate the righteousness of such concepts. This situation is difficult to justify on medical grounds and could contribute to public confusion or disquiet. This review will summarise the most important points of disagreement, with the intention of stimulating a debate within the scientific community.

A concise historical review

In the early 1950s, mechanical ventilators made it possible to support respiration in patients with irreversible total brain damage. This gave rise to questions about the timing of death and the duty of care of clinicians towards such patients. In 1957, Pope Pius XII stated two principles: that resuscitation techniques, being ‘extra-ordinary’ means, could be withdrawn before circulatory arrest occurred and that the precise moment of death cannot be deduced from any religious or moral principle, and is therefore a matter for the competence of clinicians [1]. Two years later, Jouvet suggested the possibility of diagnosing the death of the central nervous system using the electroencephalogram (EEG) [2]. In the same year, Mollaret and Goulon described the clinical picture associated with this condition [3].

Subsequent discussion started to consider the ethical and legal aspects of irreversible coma [4]. Progress in surgical techniques and immunosuppression and the diffusion of renal dialysis (which decreased the urgency for kidney transplantation) all contributed to a growing demand for organs which living, related donors could not supply. This led to consideration of brain-dead patients as a potential source [5, 6, 7].

In autumn 1967 the first heart transplantation took place. One month later an “Ad hoc Committee to Study the Problems of the Hopelessly Unconscious Patient” was convened at Harvard Medical School. By the end of this work, it changed its title to “Ad hoc Committee to examine the Definition of Brain Death” [7]. Its report defined “irreversible coma as a new criterion for death” (Appendix, quotation 1): it described the signs of BD, the appropriate procedures to declare its presence, the most relevant legal issues and the justifications for this new criterion [8].

A rational approach to BD was developed by Capron (1978) [9] and Bernat (1981) [10], in order to demonstrate the equivalence between cardiorespiratory and neurological standards for determining death.

In 1981, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioural Research proposed two alternative ways to justify BD: the “primary organ” concept, according to which cardiorespiratory functions are mere prerequisites for brain function (Appendix, quotation 2) [11] and the “loss of integrated functioning of the organism”. The Commission also produced a model statute, the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) (Appendix, quotation 3).

In less than 20 years, nearly all developed countries enacted laws or statutes that encapsulated the principles of the report.

A continuing controversy

The most important controversies regarding BD are reported below, grouped according to issues for convenience of presentation.

The utilitarian aspect of the brain death concept

Some authors criticised the strict utilitarian connection between transplant policies and BD [7, 12, 13], whose definition appears to be “the product of conceptual gerrymandering to solve a social problem” [12], or “a political decision (...) prompted by a growing need for organs for transplantation” [13]. Such an “inherently unstable” [12] utilitarian position could lead to attempts at stretching the definition, as has already happened [14, 15, 16].

All these statements might be somewhat morally disturbing. Nevertheless, they do not mean that the BD concept is per se scientifically untenable.

Definitions and criteria

A primary problem is that BD is defined in two different ways: in the USA and in most European countries a “whole brain” definition is adopted, while in the UK a “brainstem” definition is used (Table 1) [17]. Besides, major diversities exist among different countries in the procedures for diagnosing BD (Table 2) [18].

Perhaps more pressing is the discrepancy between the “whole brain” definition (Table 1) and the correspondent criteria, which demonstrate the irreversible cessation of only a part of all known intracranial functions [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. Actually, the activity of the pituitary gland, the control of cardiovascular tone and thermoregulation are virtually ignored.

It is not clear why neurological signs of BD were privileged, compared to the neuro-endocrine and autonomic ones. As a matter of fact, neither indispensability for biological survival [25] nor possibility of being replaced can be assumed as definite reasons for such a choice. Even control of ventilation, which can be considered the most vital intracranial function, is replaceable by either artificial ventilation or diaphragmatic pacing. Not surprisingly, the variable persistence of neuro-endocrine and autonomic intracranial functions has been described in many brain-dead patients [19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]. Furthermore, some residual electrical activity has also been demonstrated in conditions consistent with BD [19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 29, 30, 31].

Acknowledging that “the designation ‘whole brain’ death is an approximation”, Bernat suggested the identification of BD as the destruction of a theoretically determinable critical neuronal population [29] and quoted Pallis’ proposal of defining BD as the permanent cessation of functioning of the brain as a whole (not of the whole brain) [32]. Yet, how much of the brain must die has neither been clearly stated nor incorporated in the definition.

All these problems are attenuated by the necessity to demonstrate a sufficient cause of BD and to exclude every confounding factor, as required nearly everywhere.

The purported equivalence between brain death and death

In the last decade, what—with very few exceptions [30, 33, 34]—was an extremely united front of BD supporters started to break up. Some authors challenged the equivalence of BD to the death of the patient [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40]. The most authoritative view justifying this equivalence is the theory of “the brain as the central integrator of the body”. BD must be legitimately regarded as death of the individual because it induces a loss of the somatic integrative unit: in BD, the body is no more an integrated organism but a mere and rapidly disintegrating collection of organs which have lost forever the capacity of working as a co-ordinated whole (Appendix, quotation 4) [10]. This rationale is the only one officially accepted [11, 12, 35].

Such a theory has been strongly criticised, as biological death cannot be proven with certainty in BD. Actually, not all brain-dead patients inexorably deteriorate to cardiovascular collapse in a short time and some of them show an adequate level of biological integration for weeks or months (up to more than 14 years in one case) [12, 22, 24, 35, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42]. A brain-dead patient can assimilate nutrients, eliminate wastes, fight infections, heal wounds, carry out a pregnancy and so on.

Somehow, it seems that the “central integrator” theory rests more on what we think should happen to brain-dead patients, according to the definition, than on what can happen in reality. In particular, Shewmon outlined that this theory appears to be an a posteriori philosophical and moral elaboration of what had already been codified into laws and implemented in practice [35]. He confirmed his position by quoting the statement of Cranford and Smith about patients in permanent vegetative state (PVS): “It would be tempting to call [permanently unconscious patients] dead and then retrospectively apply the principles of death, as society has done with brain death” [43].

An alternative rationale could be that BD causes the loss of essential human properties (conscience, reasoning, feelings, memories, ...) and personhood. The permanent loss of these functions would identify the patient’s death (the “cortical death”), even in the presence of some lower neurological activities (breathing and swallowing), of spontaneous but unintentional movements and of thermoregulation [19, 20]. The major problems of this approach are clinical (the certain and permanent absence of all upper neurological functions is very hard to predict [44, 45]), moral (inclusion in BD of patients in PVS, dementia and anencephaly) and procedural (separation of the death of the person from the death of the organism, or the possibility of burying still breathing “cadavers”). This approach is far from finding unanimous favour and has not found any legal application yet.

Organ retrieval without brain death: forward to the past (the non-heart-beating organ donor protocols)

The definition of the vital status of brain-dead donors has been circumvented by the introduction of non-heart-beating organ donor (NHBD) protocols. The Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) recognised two patient subsets [46]: uncontrolled NHBD (organ retrieval following unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation after unexpected cardiorespiratory arrest) and controlled NHBD (organ procurement following a planned withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies which are considered futile or excessively burdensome by the patient and/or his family). Obviously, as for controlled NHBD patient, the cessation of cardiorespiratory functions is intended as “spontaneously irreversible” [47].

The period of time between asystole and organ harvesting is variable. The Institute of Medicine, after surveying the existing NHBD protocols (waiting time ranging from 0–5 min), recommended a 5-min interval [48]. The SCCM Ethics Committee stated that “no less than two minutes is acceptable, no more than five minutes is necessary” [46].

Actually, at the time of organ retrieval, the donor will probably not be dead according to either of the UDDA criteria (Appendix, quotation 3). After less than 5 min of asystole, irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions can not be demonstrated: harvested hearts have been successfully implanted [49, 50] and spontaneous restoration of cardiac function after more than 5 min of asystole has been reported [51, 52, 53, 54, 55]. Also, given the short time interval, the irreversible cessation of all intracranial functions can not be claimed as certain [46].

This whole issue is still actively debated [46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63], especially because of the potential yield of NHBD protocols [50, 60, 63].

Organ retrieval without death: revising the dead donor rule

Some authors deem that current BD criteria, though not satisfactory for the diagnosis of death, are sufficient for organ harvesting from previously consenting patients; consequently, they have suggested abandoning the dead donor rule, which states that patients must be dead before organ retrieval and death must be neither caused nor hastened by the retrieval [12, 21, 22, 24, 40]. Arnold and Youngner, for instance, proposed relying entirely on informed consent and on a “violate-no-interest” approach [12], which is nonetheless highly problematic as it could be considered active killing of a previously consenting patient [21].

Adapting rules and definitions

Different solutions have been proposed in order to reconcile the reality of BD and transplant medicine. Halevy and Brody proposed abandoning the hypothesis of the possible definition of BD as an event that sharply separates life and death at an arbitrary point. Yet, the satisfaction of current tests for BD can be considered an appropriate criterion for organ retrieval [23].

In Denmark, after very large community involvement, the Danish Council of Ethics recommended to maintain the traditional cardiorespiratory criterion for death, but recognised the particular significance of the situation identified by BD (“a condition ... which absolutely excludes the possibility of stopping the death process “ [64]); in this condition, every support should be forgone or maintained to permit organs retrieval: “such an intervention is cause for the conclusion of the process of death, but is not the cause of death” [64]. Yet, the Danish Parliament preferred to base the law on the more customary concept of BD.

On legal grounds, a new German law on transplants allows organ retrieval after irreversible loss of all intracranial functions without expressly recognising that donors are dead [37]. In the USA, laws in New Jersey and New York enable the application of BD definition only when respecting the stated view of the patient [65]. A recent Japanese law provides that only the patients who have agreed to donate their organs can be declared brain-dead [66].

Revising the brain death definition

The above-described state of reflection on BD can appear more complex than the everyday clinical activity in ICUs would suggest. Nevertheless, some authors maintain that there is only a superficial and fragile consensus among health care workers on this issue, beneath which little agreement (and sometimes great confusion) can be found [22, 35, 67].

Our view is that, as was originally proposed by the Harvard Committee, BD is much more a moral than a scientific concept. According to the Committee’s Report (whose only reference was the Pope’s address [1]), there were two reasons to introduce this concept (both clearly moral): to allow withdrawal of life support in irreversibly comatose patients and to provide justification for the retrieval of vital organs (Appendix, quotation 1). And Henry Beecher, chairman of the Committee, stated:

“At whatever level we choose to call death, it is an arbitrary decision. Death of the heart? The hair still grows. Death of the brain? The heart may still beat. The need is to choose an irreversible state where the brain no longer functions. It is best to choose a level where, although the brain is dead, usefulness of other organs is still present. This, we have tried to make clear in what we have called the new definition of death. (...). Here we arbitrarily accept as death, destruction of one part of the body; but it is the supreme part, the brain. (...). Dying is a continuous process; while death may occur at a discrete time, we are not able to pinpoint it.” [68].

The Committee’s reasoning seems to have been the following: in the process of dying it is possible to identify clinically a condition in which patients can be defined irreversibly sufficiently dead in order to forgo life support and to retrieve vital organs. This is clearly a moral proposal, and such it remains even if the definition of the criteria at which time it applies is a scientific matter.

In 1981, Bernat tried to demonstrate that BD scientifically identifies the biological death of the organism, putting forward the theory of the “brain as the central integrator” (Appendix, quotation 4) [10]. Unfortunately, as already seen, such a position is empirically untenable [12, 22, 24, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40].

So, it seems that we are back where we started. Yet, though we are still unable to pinpoint death, in 35 years we have learnt at least three things:

-

1.

In some cases of “brain dead”, some residual intracranial functions can be retained;

-

2.

A level of biological integration can also remain, sufficient for prolonged biological maintenance;

-

3.

Even in such cases, however, recovery of those intracranial functions upon which the BD declaration is based never occurred, confirming that their loss is irreversible.

In our opinion, the first two points are irrelevant to the social and moral acceptability of the original Committee’s position, which is conversely strengthened by the third one. Yet, they strongly question the use of the term “brain death”, as—to be rigorous—the clinical condition they refer to corresponds neither to the loss of all intracranial functions nor to the patients’ biological death (at least not always).

A simple alternative could be to revert to the original term of “irreversible coma” (Appendix, quotation 1) or, more precisely, “irreversible apnoeic coma” (IAC), understood not as equivalent to death, but as describing a particular condition in which life support should be legitimately forgone and organs can be retrieved from consenting patients. This term clearly differentiates IAC from deep coma (in which brainstem functions are maintained) (Table 3), a condition which—if recovery does not occur—typically turns into either a vegetative state, in which wakefulness (eye opening) is regained, or IAC [17]. Furthermore, this definition should have no consequences for transplantation: the patient’s condition, the previously obtained informed consent and the nobility of the action could preserve the process of organ retrieval from such donors as socially acceptable, even admitting the problematic definition of their vital status.

In other words, we think that this semantic change, while better describing the situation, neither substantially challenges the status quo nor undermines the righteousness of the traditional criteria, whose usefulness in identifying this condition has been confirmed. Obviously, it has to be adequately explained to lay public.

Maybe the problem could be re-assessed by reconsidering how intensive care alters dying and death. In this sense, the task of the new-born ESICM Working Group on the diagnosis of death and on post mortem medical interventions performed in intensive care units is an essential step in order to (re)define the vital status of these patients, taking account of both residual intracranial functions and biological integration, which can be present in IAC.

Conclusions

Medicine can demonstrate the irreversible loss of cortical and brainstem functions, thus identifying an extremely advanced point of no return in the dying process, the irreversible apnoeic coma (IAC). The definition of the vital status of IAC patients is more a task for society at large than a medical one. Yet, we argue that, in such patients, the retrieval of vital organs can be morally and socially permitted subject to legally acceptable consent.

We believe that, in line with the views expressed by the Danish Council of Ethics [64], this approach creates consistency between current practice and underlying reality, it is clear and understandable to the public and leaves much scope for the involvement of society at large.

References

Pius XII (1958) The prolongation of life: an address of Pope Pius XII to an international congress of Anaesthesiologists. The Pope speaks 4:393–398

Jouvet M (1959) Diagnostic électro-souscorticographique de la mort du système nerveux central au cours de certains comas. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 3:52–53

Mollaret P, Goulon M (1959) Le coma dépassé (mémoire préliminaire). Rev Neurol 101:3–15

Schwab RS, Potts F, Bonazzi A (1963) EEG as an aid in determining death in the presence of cardiac activity (ethical, legal and medical aspects). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 15:147–148

Wolstenholme GEW, O’Connor M (1966) Ethics in medical progress: with special reference to transplantation. A Ciba Foundation Symposium. Little, Brown & Co., Boston

DeVita MA, Snyder JV, Grenvik A (1993) History of organ donation by patients with cardiac death. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 3:113–129

Giacomini M (1997) A change of heart and a change of mind? Technology and the redefinition of death in 1968. Soc Sci Med 44:1465–1482

Ad hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death (1968) A definition of irreversible coma: report of the Ad hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA 205:85–88

Capron AM (1978) Legal definition of death. Ann N Y Acad Sci 315:349–362

Bernat JL, Culver CM, Bernard G (1981) On the definition and criterion of death. Ann Intern Med 94:389–394

President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioural Research (1981) Defining death: a report on the medical, legal and ethical issues in the determination of death. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Arnold RM, Youngner SJ (1993) The dead donor rule: should we stretch it, bend it or abandon it? Kennedy Inst Ethics J 3:263–278

Cranston RE (2001) The diagnosis of brain death. N Engl J Med 345 (8):616

Hoffenberg R, Lock M, Tilney N, Casabona C, Daar AS, Guttmann RD, Kennedy I, Nundy S, Radcliffe-Richards J, Sells RA (1997) Should organs from patients in permanent vegetative state be used for transplantation? Lancet 350:1320–1321

Ivan LP (1990) The persistent vegetative state. Transplant Proc 22:993–994

Truog RD, Fletcher JC (1989) Anencephalic newborns. Can organs be transplanted before death? N Engl J Med 321:388–390

Young BG (1998) Major syndromes of impaired consciousness. In: Young BG, Ropper AH, Bolton CF (eds) Coma and impaired consciousness: a clinical perspective. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 39–78

Wijdicks EFM (2002) Brain death worldwide. Accepted fact but no global consensus in diagnostic criteria. Neurology 58:20–25

Truog RD, Fackler JC (1992) Rethinking brain death. Crit Care Med 20:1705–1713

Veatch RM (1993) The impending collapse of the whole-brain death definition of death. Hastings Cent Rep 23 (4):18–24

Truog RD (1997) Is it time to abandon brain death? Hastings Cent Rep 21:29–37

Singer P (1994) How death was redefined. In: Singer P Rethinking life and death. The collapse of our traditional ethics. St. Martin’s Press, New York, pp 20–37

Halevy A, Brody B (1993) Brain death: reconciling definitions, criteria and tests. Ann Intern Med 119:519–525

Kerridge IH, Saul P, Lowe M, McPhee J, Williams D (2002) Death, dying and donation: organ transplantation and the diagnosis of death. J Med Ethics 28:89–94

Truog RD, Robinsn WM (2001) The diagnosis of brain death. N Engl J Med 345 (8):617

Outwater KM, Rockoff MA (1984) Diabetes insipidus accompanying brain death in children. Neurology 34:1243–1246

Fiser DH, Jimenez JF, Wrape V, Woody R (1987) Diabetes insipidus in children with brain death. Crit Care Med 15:551–553

Hohenegger M, Vermes M, Mauritz W, Redl G, Sporn P, Eiselberg P (1990) Serum vasopressin (AVP) levels in polyuric brain-dead organ donors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 239:267–269

Bernat JL (1992) How much of the brain must die in brain death? J Clin Ethics 3:21–26

Evans DW, Hill DJ (1989) The brainstems of organ donors are not dead. Catholic Medical Quarterly 40:113–121

Facco E, Munari M, Gallo F, Volpin SM, Behr AU, Baratto F, Giron GP (2002) Role of short latency evoked potentials in the diagnosis of brain death. Clin Neurophysiol 113:1855–1866

Pallis C (1983) ABC of brainstem death. BMJ Publisher, London

Jonas H (1974) Against the stream. Comments on the definition and redefinition of death. In: Jonas H. Philosophical essays: from ancient creed to technological man. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp 132–140

Byrne P, O’Reilly S, Quay PM (1979) Brain death—an opposing viewpoint. JAMA 242 (18):1985–1990

Shewmon DA (1997) Recovery from “brain death”: A neurologist’s Apologia. Linacre Quarterly 64:30–96

Shewmon DA (1998) Chronic “brain death”: meta-analysis and conceptual consequences. Neurology 51:1538–1545

Shewmon DA (1998) “Brain-stem death”, “brain death” and death: a critical re-evaluation of the purported evidence. Issues Law Med 14:125–145

Shewmon DA (1999) Spinal shock and ‘brain death’: somatic pathophysiological equivalence and implications for the integrative-unity rationale. Spinal Cord 37:313–324

Shewmon DA (2001) The brain and somatic integration: insights into the standard biological rationale for equating “brain death” with death. J Med Philos 26 (5):457–478

Hill DJ (2002) Honesty is best policy. BMJ 325:836

Cranford R (1998) Even the dead are not terminally ill anymore. Neurology 51:1530–1531

Baumgartner H, Gerstenbrand F (2002) Diagnosing brain death without a neurologist. BMJ 324:1471–1472

Cranford RE, Smith DR (1987) Consciousness: the most critical moral (constitutional) standard for human personhood. Am J Law Med 13 (2–3):233–248

Wade TD (2001) Ethical issues in diagnosis and management of patients in the permanent vegetative state. BMJ 322:352–354

Shewmon DA, Holmes GL, Byrne PA (1999) Consciousness in congenitally decorticate children: “developmental vegetative state” as self-fulfilling prophecy. Dev Med Child Neurol 41 (6):364–374

The Ethics Committee, American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine (2001) Recommendations for non-heart-beating organ donation. A position paper. Crit Care Med 29 (9):1826–1831

DuBois JM (1999) Non-heart-beating organ donation: a defence of the required determination of death. J Law Med Ethics 27:126–136

Institute of Medicine (1997) Non-heart-beating organ transplantation: medical and ethical issues in procurement. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pp 40–41

Meninkoff J (1998) Doubts about death: the silence of the Institute of Medicine. J Law Med Ethics 26:157–165

Van Norman GA (2003) Another matter of life and death. What every anesthesiologist should know about the ethical, legal and policy implication of the non-heart-beating cadaver organ donor. Anesthesiology 98:763–773

Quick G, Bastiani B (1994) Prolonged asystolic hypercalemic cardiac arrest with no neurologic sequelae. Ann Emerg Med 24:305–311

Mertens P, Vandekerckhove Y, Mullir A (1993) Restoration of spontaneous circulation after cessation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Lancet 341:841

Maeda H, Fujita MQ, Zhu BL, Yukioka H, Shindo M, Quan L, Ishida K (2002) Death following spontaneous recovery from cardiopulmonary arrest in a hospital mortuary: ‘Lazarus phenomenon’ in a case of alleged medical negligence. Forensic Sci Int 127:82–87

Maleck WH, Piper SN, Triem J, Boldt J, Zittel FU (1998) Unexpected return of spontaneous circulation after cessation of resuscitation (Lazarus phenomenon). Resuscitation 39:125–128

Bray JG (1993) The Lazarus phenomenon revisited. Anesthesiology 78:991

Youngner SJ, Arnold RM, DeVita MA (1999) When is dead? Hastings Cent Rep 29 (6):14–21

Lynn J (1993) Are the patients who become organ donors under the Pittsburgh Protocol for ‘non-heart-beating donors’ really dead? Kennedy Inst Ethics J 3:167–178

Fox RC (1993) An ignoble form of cannibalism: reflections on the Pittsburgh Protocol for procuring organs from non-heart-beating donors. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 3:231–239

Herdman R, Beauchamp TL, Potts JT Jr (1998) The Institute of Medicine’s report on non-heart-beating organ transplantation. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 8:83–90

Kootstra G (1997) The asystolic, or non-heart-beating, donor. Transplantation 63:917–921

Zamperetti N, Bellomo R, Ronco C (2003) Defining death in non heart beating organ donors. J Med Ethics 29:182–185

Truog RD (2003) Organ donation after cardiac death. What role for anesthesiologists? Anesthesiology 98:599–600

Solomon MZ (2003) Donation after cardiac death. Non-heart-beating organ donation deserves a green light and hospital oversight. Anesthesiology 98:763–773

Danish Council of Ethics (1988). Death criteria: a report. The Danish Council of Ethics, Denmark

Beresford HR (1999) Brain death. Neurol Clin 17 (2):295–306

Akabayashi A (1997) Finally done—Japan’s decision on organ transplantation. Hastings Cent Rep 27:47

Youngner RM, Landefeld CS, Coulton CJ, Juknialis BW, Leary M (1989) “Brain death” and organ retrieval. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge and concepts among health professionals. JAMA 261:2205–2210

Beecher H (1971) The new definition of death. Some opposing viewpoints. Int J Clin Pharmacol 5:120–121

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

No funds were requested/used to support this work.

The authors strongly support transplant medicine and are actively involved at local level in their respective national transplant programmes.

An editorial regarding this article can be found in the same issue http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2164-1

Quotations

Quotations

Quotation 1. The opening words of the report of the Ad hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death [8]

“Our primary purpose is to define irreversible coma as a new criterion for death. There are two reasons why there is a need for a definition: (1) improvement in resuscitative and supportive measures have led to increased efforts to save those who are desperately injured. Sometimes these efforts have only a partial success so that the result is an individual whose heart continues to beat but whose brain is irreversibly damaged. The burden is great on patients who suffer permanent loss of intellect, on their families, on the hospitals, and on those in need of hospital beds already occupied by these comatose patients. (2) Obsolete criteria for the definition of death can lead to controversy in obtaining organs for transplantation.”

Quotation 2. The definition of the “primary organ view” concept by the President’s Commission [11]

“On this view, the heart and lungs are not important as basic prerequisites to continue life but rather because the irreversible cessation of their functions shows that the brain had ceased functioning (...). The “primary organ” view would be satisfied with a statute that contained only a single standard—the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain. Nevertheless, as a practical matter, the view is also compatible with a statute establishing irreversible cessation of respiration and circulation as an alternative standard, since it is inherent in this view that the loss of spontaneous breathing and heartbeat are surrogates for the loss of brain function.”

Quotation 3. The Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA), which was a product of the President’s Commission

“An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead.”

Quotation 4. The concept of the “brain as the central integrator organ”, as formulated by Bernat [10]

“The criterion for cessation of functioning of the organism as a whole is permanent loss of functioning of the entire brain. This criterion is perfectly correlated with the permanent cessation of functioning of the organism as a whole because the brain is necessary for the functioning of the organism as a whole. It integrates, generates, interrelates, and controls complex bodily activities. A patient on a ventilator with a totally destroyed brain is merely a group of artificially maintained subsystems since the organism as a whole has ceased to function. (...). Destruction of the brain produces apnoea and generalised vasodilatation; in all cases, despite the most aggressive support, the adult heart stops within one week, and that of the child within two weeks. Thus, when the organism as a whole has ceased to function, the artificially supported ‘vital’ subsystems quickly fail.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zamperetti, N., Bellomo, R., Defanti, C.A. et al. Irreversible apnoeic coma 35 years later. Intensive Care Med 30, 1715–1722 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-2106-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-2106-3