Abstract

Purpose

Although dozens of studies have associated vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam with increased acute kidney injury (AKI) risk, it is unclear whether the association represents true injury or a pseudotoxicity characterized by isolated effects on creatinine secretion. We tested this hypothesis by contrasting changes in creatinine concentration after antibiotic initiation with changes in cystatin C concentration, a kidney biomarker unaffected by tubular secretion.

Methods

We included patients enrolled in the Molecular Epidemiology of SepsiS in the ICU (MESSI) prospective cohort who were treated for ≥ 48 h with vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam or vancomycin + cefepime. Kidney function biomarkers [creatinine, cystatin C, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)] were measured before antibiotic treatment and at day two after initiation. Creatinine-defined AKI and dialysis were examined through day-14, and mortality through day-30. Inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to adjust for confounding. Multiple imputation was used to impute missing baseline covariates.

Results

The study included 739 patients (vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam n = 297, vancomycin + cefepime n = 442), of whom 192 had cystatin C measurements. Vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam was associated with a higher percentage increase of creatinine at day-two 8.04% (95% CI 1.21, 15.34) and higher incidence of creatinine-defined AKI: rate ratio (RR) 1.34 (95% CI 1.01, 1.78). In contrast, vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam was not associated with change in alternative biomarkers: cystatin C: − 5.63% (95% CI − 18.19, 8.86); BUN: − 4.51% (95% CI − 12.83, 4.59); or clinical outcomes: dialysis: RR 0.63 (95% CI 0.31, 1.29); mortality: RR 1.05 (95%CI 0.79, 1.41).

Conclusions

Vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam was associated with creatinine-defined AKI, but not changes in alternative kidney biomarkers, dialysis, or mortality, supporting the hypothesis that vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam effects on creatinine represent pseudotoxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam was associated with an increased risk of creatinine-defined acute kidney injury, but not changes in alternative kidney function biomarkers (cystatin C, blood urea nitrogen), or downstream clinical outcomes associated with true acute kidney injury (dialysis or mortality). These findings suggest that the association of vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam with creatinine-defined acute kidney injury may represent pseudotoxicity |

Introduction

Vancomycin (VN) and piperacillin–tazobactam (PT) are two cornerstones of antibiotic therapy in acutely ill patients with sepsis. In a recent analysis of 576 United States hospitals, these agents were the two most commonly used antibiotics, accounting for over 13 million days of antibiotic therapy in 2016 [1]. Given the key role of this antibiotic combination, the emergence of evidence linking VN + PT to acute kidney injury (AKI) is a major drug safety concern [2, 3]. Nearly fifty observational studies have demonstrated this association, with a recent meta-analysis suggesting VN + PT increases AKI risk two-fold [4]. In response to these data, some health systems have implemented large-scale initiatives to avoid the combination [2, 3].

Despite this epidemiologic evidence, the mechanism of potential interaction is unknown. VN can cause acute tubular necrosis via oxidative stress and the formation of obstructive tubular casts [5, 6]. In contrast, there is little evidence linking PT to nephrotoxicity, other than rare cases of acute interstitial nephritis [7]. Moreover, animal models have failed to demonstrate synergistic toxicity [6, 8,9,10], with some suggesting that PT may actually reduce VN nephrotoxicity [8,9,10].

The literature supporting the AKI association in humans is based on creatinine-defined AKI [4, 11]. Serum creatinine, the standard kidney function biomarker, is subject to proximal tubular secretion, which accounts for 10–40% of creatinine clearance in healthy adults and up to 60% in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [12]. Notably, both VN and PT bind to renal transporters that mediate creatinine secretion [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Thus, the association with creatinine defined AKI may represent pseudotoxicity, mediated by effects on tubular secretion of creatinine without toxic effects on kidney parenchyma.

The uncertain nature of the AKI association has created a major dilemma for bedside clinicians and health system antimicrobial stewardship programs: if VN + PT is truly nephrotoxic, the combination may contribute substantially to AKI and associated downstream effects including heightened risks of CKD, cardiovascular disease, and mortality [20, 21]; if not, avoidance of the combination could limit treatment of life-threatening infections, expose patients to toxicity from alternative antibiotics, and worsen antimicrobial resistance patterns [3, 22,23,24]. We thus aimed to examine the creatinine secretion hypothesis by contrasting changes in creatinine after antibiotic initiation with changes in cystatin C (Cys-C), a well-validated biomarker of kidney function that is unaffected by tubular secretion [25, 26]. We hypothesized that VN + PT would be associated with changes in creatinine, but not associated with changes in cystatin C, need for dialysis, or mortality, findings that would support the premise that VN + PT-associated creatinine changes do not reflect changes in kidney function or underlying tissue injury. Parts of this work were presented in abstract form at the 2021 American Thoracic Society conference [27].

Methods

Design and population

This study was part of the Molecular Epidemiology of SepsiS in the ICU (MESSI) project [28], an ongoing prospective observational study that enrolls patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with severe sepsis or septic shock meeting sepsis-2 criteria [29]. MESSI exclusion criteria are a lack of commitment to life-sustaining measures or unwillingness to provide consent. We identified MESSI patients treated with VN + PT or VN + cefepime (CP) for ≥ 48 h, with each drug initiated within ± 48 h of ICU admission (the antibiotic cohort). We chose CP as the comparator because it’s commonly used for empiric sepsis treatment, and when combined with VN, has been associated with lower AKI risk compared to VN + PT [30, 31]. The index date was the date and time of concomitant antibiotic initiation. We excluded patients from the antibiotic cohort for end stage renal disease, dialysis within 14 days before the index date, or baseline AKI, defined as an index creatinine ≥ 1.5 times higher than baseline creatinine. Index creatinine was the last value obtained before the index date. Baseline creatinine was the average of outpatient or hospital discharge creatinine values from 365 days before to 7 days before hospital admission [32]. Where these data were missing, baseline was defined as the lowest value within seven days before ICU admission.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were kidney function biomarker concentrations (creatinine and Cys-C) measured at index and at day two (48–72 h) after combination antibiotic initiation (Fig. 1). We chose Cys-C because it is a validated kidney function biomarker [26] that does not undergo tubular secretion [25], and has been shown to identify AKI earlier than creatinine in patients with sepsis [33, 34]. Cys-C was measured with electrochemiluminescence from stored plasma biospecimens [35]. We included patients in the Cys-C analyses (i.e., the Cys-C sub-cohort) if the timing of their blood draws aligned with a priori defined windows for baseline and follow-up Cys-C measurement (Fig. 1). The protocol for collection and storage of plasma samples is described in the appendix, and details of plasma sample availability are shown in Table S1. Serum creatinine concentrations between index and day two were obtained from Penn’s electronic health record (EHR) database for all patients in the antibiotic cohort. For the subset of patients included in the Cys-C cohort, we used clinical creatinine measurements that were obtained closest in time to the plasma sample used to measure Cys-C. For antibiotic cohort patients not included in the Cys-C cohort (Fig. 1c), we randomly selected both index and day two creatinine values from those measured clinically during the baseline and follow-up time periods (Fig. 1b).

Framework for patient inclusion, index date, and follow-up for measures of kidney function. The figure shows follow-up definitions during combined exposure to vancomycin (teal bars) and a beta-lactam (light blue bars, either piperacillin–tazobactam or cefepime). A Two scenarios by which patients could enter the antibiotic cohort. For both scenarios, the index date was defined as the date and time when combined therapy started. B Time frame, with respect to antibiotic exposure, for measurement of kidney function markers at baseline and during follow-up. The period for baseline cystatin C measurement was the 24 h period immediately prior to the index date. The period for follow-up cystatin C measurement was the period from 48 to 72 h after the index date. For direct comparative analyses with cystatin C, change in serum creatinine was measured over the same time frame. Follow-up for KDIGO defined acute kidney injury (AKI) began on the index date and continued until: lapse in concomitant antibiotic exposure > 48 h, hospital discharge, death, or 14 days after the index date. We followed AKI episodes for 7 days after onset to assess severity stage and initiation of renal replacement therapy. Follow-up for mortality began on the index date and continued until death or until 30 days after the index date. C Alignment of antibiotic follow-up with the underlying time-line of the MESSI cohort study. Patients were included in cystatin C analyses if the timing of their blood draws aligned with the allowable time periods for baseline and follow-up cystatin C measurement (hashed gray-white boxes) as defined in B. The vertical solid black line denotes ICU admission (MESSI hour zero) and the gray shaded box is the period around MESSI hour zero during which eligible antibiotic courses had to be initiated (± 48 h). MESSI day zero plasma samples (red X) were obtained from residual citrated plasma collected at emergency department presentation, or for patients transferred from the hospital ward, at the point closest to ICU admission (dashed vertical lines around hour zero). Follow-up residual plasma was obtained approximately 48 h after ICU admission (dashed vertical lines around hour 48)

Because Cys-C was not available for all patients in the antibiotic cohort, we examined blood urea nitrogen (BUN) as a secondary biomarker (obtained from the EHR as creatinine above) of glomerular filtration that is not subject to tubular secretion [36]. Lastly, to quantitatively test the hypothesis that the change in creatinine after antibiotic initiation differs from the change in comparator biomarkers, we calculated ratios of Cys-C concentration:creatinine concentration and BUN concentration:creatinine concentration at baseline and day two.

Secondary clinical outcomes were creatinine-defined AKI though day 14, dialysis, and 30-day mortality (Fig. 1). AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) creatinine criteria [37], with index creatinine used as the reference for phenotyping.

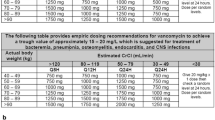

Data collection

MESSI personnel collected plasma biospecimens, demographics and comorbidity variables. Medications, laboratory values, and dialysis orders were obtained via EHR query. Potential confounders were selected a priori based on clinical knowledge and prior literature, including factors associated with AKI, severity of illness, or potential non-renal determinants of cystatin C concentration (Table 1, Table S2) [38,39,40]. Concomitant medication and laboratory variables were assessed during the 24 h before the index date. For each laboratory measure, the value most proximate to cohort entry was collected. Dosing of VN, PT, and CP was calculated from doses administered during the first 24 h after the index date (see Table S3 for details).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and missing data

Baseline covariate balance was examined using standardized mean differences (SMD), with absolute SMD values > 0.1 indicative of imbalance [41]. Missing values were observed for several baseline laboratory and vital sign measures (Table S4). We imputed missing data using multiple imputation, producing fifty imputation data sets (see appendix for details). We estimated time to KDIGO defined AKI with Kaplan–Meier curves.

Inverse probability of treatment weighting

We adjusted for confounding using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW), calculated from the propensity score for VN + PT treatment. IPTW analysis was applied to the multiply imputed datasets using the within-imputation method [42], wherein propensity score estimation and weighted outcome modeling is repeated separately in each dataset, then combined using standard methods (Figure S1). Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression conditional on covariates listed in Table 1 (antibiotic cohort) and Table S2 (Cys-C sub-cohort). Propensity scores were estimated separately in the antibiotic cohort and the Cys-C sub-cohort to ensure correct propensity score model specification. Covariates showing residual imbalance after IPTW were included in weighted outcome models.

Outcome models

We modeled day two kidney function biomarkers using IPTW linear regression, adjusted for baseline biomarker concentration [43]. We log-transformed biomarker concentrations for analysis and exponentiated model coefficients to provide the percentage difference between groups. Secondarily, we examined the change in biomarker concentrations at day two as dichotomous variables, comparing the incidence of ≥ 50% increases in biomarker concentrations from baseline to day two with IPTW Poisson regression models. Analysis of day two creatinine and BUN concentrations were conducted in the Cys-C sub-cohort, and secondarily in the full antibiotic cohort (to examine consistency of results in the Cys-C subcohort compared to those from the antibiotic cohort). IPTW Poisson regression was also used to model incidence rate ratios (IRR) for KDIGO defined AKI, dialysis, and mortality.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses included: (1) repeating all models after restricting to patients with overlapping propensity scores (to examine the impact of positivity assumption violations) [44]; (2) repeating all models after restricting to patients with propensity scores between the 1st and 99th percentiles of the overlapping propensity scores (to examine potential unmeasured confounding in the tails of the propensity score distributions) [44]; (3) repeat analysis of day two Cys-C concentrations after excluding patients treated with corticosteroids (to examine potential confounding by corticosteroid exposure); (4) repeat analysis of KDIGO defined AKI after restricting follow-up to 7 days; (5) repeating analyses with additional adjustment for calendar year (to examine potential confounding from practice changes over time); and (6) analysis of the incidence of BUN increases ≥ 50% from baseline through day 14 (to examine consistency of day two analysis with results from later time points).

Results

Study population

The study included 739 patients in the antibiotic cohort, 192 of whom had plasma samples for Cys-C analysis (Fig. 2). Patients in the Cys-C sub-cohort had similar baseline kidney function, severity of illness scores, and need for mechanical ventilation compared to patients without Cys-C samples (Table S7). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1 (antibiotic cohort) and table S2 (Cys-C sub-cohort). Before weighting, VN + PT patients had higher severity of illness scores, lower baseline eGFR, higher lactate concentration, and more frequent diabetes mellitus and cirrhosis. Weighting balanced covariates in both cohorts. In the Cys-C sub-cohort, there was minor residual imbalance in respiratory rate, hypertension, cancer, and solid organ transplant; these covariates were included in the weighted outcome models.

Selection of patients from parent sepsis cohort into study-specific analytic cohorts. The study sample was selected from patients enrolled in MESSI from September 2008 to July 2020 (n = 3303). ESRD end stage renal disease, AKI acute kidney injury, HD hemodialysis, VN + PT vancomycin + piperacillin–tazobactam, VN + CP vancomycin + cefepime

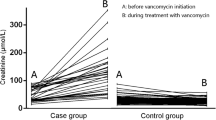

Kidney function biomarkers at day two

VN + PT was associated with significantly higher average creatinine concentrations (Table 2) and a higher frequency of creatinine increases of ≥ 50% (Table 3). In contrast, VN + PT was associated with non-significantly lower average Cys-C concentrations and a similar frequency of Cys-C increases of ≥ 50% compared to VN + CP. BUN measures did not differ significantly between groups at day two, nor did the rate of ≥ 50% increases of BUN through day 14 (Table S8). Lastly, both the Cys-C:creatinine ratio and BUN:creatinine ratio were significantly lower in the VN + PT group vs. the VN + CP group, indicating that creatinine increased to a significantly greater extent than either Cys-C or BUN by day two (Table 2).

Clinical outcomes

The time to KDIGO-defined AKI is shown in Figure S4. Crude and weighted clinical outcome analyses are shown in Table 4. VN + PT was associated with a significantly higher rate of creatinine-defined AKI at day-14. The association was attenuated and non-significant when restricting to stage 2 or higher events. Similarly, VN + PT was not associated with the rate of dialysis or mortality after weighting.

Sensitivity analyses

Results were minimally changed by propensity score trimming (Table S9, Table S10), or adjustment for calendar year (Table S11). Cys-C results were similar after excluding corticosteroid exposed patients (Table S12). Lastly, the 7-day analysis of KDIGO-AKI provided similar results to the 14-day analysis (Table S13).

Discussion

VN + PT was associated with increased creatinine concentrations at day two and an increased rate of creatinine-defined AKI at day 14. In contrast, VN + PT was not associated with changes in Cys-C or BUN at day two. We further observed that VN + PT-associated AKI did not translate into higher dialysis or mortality rates. Taken together, these findings suggest that the association with AKI represents pseudotoxicity, and that avoidance of this essential antibiotic combination may be unwarranted.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of VN + PT to employ Cys-C as an alternative to creatinine, which allowed us to conduct the most direct mechanistic assessment of the VN + PT interaction in humans to date. Cys-C is a validated biomarker of kidney function that has a shorter half-life than creatinine [25]. Thus, the absence of any discernable effect of VN + PT on Cys-C concentrations at day two suggests that the significant increases in creatinine over that time period were not associated with underlying changes in kidney function. VN + PT also showed no association with changes in BUN, an additional kidney biomarker that does not undergo tubular secretion. These consonant findings, as well as the consistency of BUN and creatinine analyses between the Cys-C subcohort and the full antibiotic cohort, suggest that the Cys-C results are not due to selection bias.

Both piperacillin and tazobactam are substrates for organic anion transporters that have been implicated in the tubular handling of creatinine (OAT1, OAT3) [11, 13, 14, 17, 18]. In addition, VN suppresses OAT1 and OAT3 expression [11, 15, 16]. Thus, competitive inhibition of creatinine secretion and VN-mediated transporter suppression seems a plausible mechanism of increased creatinine concentration [11]. Our findings of isolated increases in creatinine that were not matched by changes in either Cys-C or BUN are consistent with this hypothesized mechanism. Our findings are also consistent with animal studies suggesting that PT does not enhance VN toxicity [6, 8,9,10], with some suggesting that PT may actually reduce VN nephrotoxicity. A caveat to the animal models is that, beyond demonstrating no adverse effect on kidney function, some have also shown that VN + PT does not increase creatinine concentrations [8, 9]. Nevertheless, regardless of mechanism, the data raise doubt that PT enhances VN-mediated nephrotoxicity.

Our analysis of Cys-C was limited to change over the first two days of treatment, which could miss potential delayed toxicity. However, Kaplan–Meier analysis suggests that VN + PT was associated with an excess of creatinine defined AKI events primarily during the first 2–3 days of treatment, in line with the significantly elevated average creatinine concentrations observed at day two. This pattern is consistent with inhibition of creatinine secretion, which would likely manifest shortly after drug initiation, as creatinine transporter inhibition happens rapidly. Given that cystatin C has a shorter half-life compared to creatinine, it seems unlikely that the early rise in creatinine reflects underlying parenchymal injury that would only manifest delayed Cys-C elevations. In addition, VN + PT was not associated with BUN changes through day-14. Taken together, these data suggest that the day two analysis of Cys-C captures the key time period during which VN + PT mediated its effects.

Based on the magnitude of creatinine change observed with other drugs affecting creatinine secretion (0.2–0.5 mg/dL) [11], creatinine-defined AKI via this mechanism should generally be associated with stage 1 episodes, reflecting relatively small increases in creatinine. We observed a substantially attenuated association between VN + PT and creatinine-defined AKI when analysis was restricted to stage 2 or higher AKI, and no association between VN + PT and patient centered outcomes such as dialysis or mortality, consistent with previous studies [45,46,47]. Schreier found no association between short courses of VN + PT and stage 2 or higher AKI, dialysis, or mortality at 60 days [45]. Similarly, Buckley showed a significant association between VN + PT and stage 1 AKI, but not stage 2 or stage 3, dialysis, or mortality [46]. Lastly, although Blevins et al. observed significant associations between VN + PT and all AKI stages, this did not translate into higher dialysis or mortality rates [47]. In contrast, Cote observed a significant association between VN + PT and higher risk of dialysis [48]. However, they examined dialysis events that occurred within 30 days of antibiotic initiation, regardless of antibiotic duration or the timing of AKI onset. Thus, it’s unclear whether dialysis initiation was attributable to drug exposure. Our study examined dialysis initiated within seven days of AKI events that occurred during antibiotic exposure, targeting events that could plausibly be attributable to drug exposure. In sum, the preponderance of evidence suggests that any potential interaction between VN + PT has limited impact on patient centered outcomes.

Only one other study has examined the VN + PT association with a biomarker other than creatinine. Kane-Gill et al. examined cell cycle arrest markers (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 [TIMP-2]∙[IGFBP7]) in patients who received VN alone, PT alone, or VN + PT [49]. They showed that urinary [TIMP-2]∙[IGFBP7] concentrations on the day after antibiotic initiation were higher for VN + PT vs. PT alone, but not different compared to VN alone. However, the analysis was not adjusted for baseline [TIMP-2]∙[IGFBP7] concentration [43]. Moreover, it’s difficult to know whether the result represents an interaction between VN + PT, the effect of VN alone, or differences in underlying severity of illness between patients treated with monotherapy versus combination therapy.

Strengths of our study include the prospective study design, extensive confounding adjustment, and multiple imputation of missing data. Our study also has limitations. First, Cys-C concentrations can be affected by body mass index, corticosteroids, thyroid activity, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and solid organ transplant [25, 40]. We mitigated confounding from these factors through IPTW analysis. IPTW balances the distribution of these factors such that their effect would influence Cys-C to a similar extent in both groups. Second, we only had Cys-C concentrations for a subset of patients. However, we showed that the Cys-C subcohort had similar characteristics to the full antibiotic cohort, and supplemented Cys-C with analysis of changes in BUN concentration. Nevertheless, it is important to note that BUN changes can reflect factors other than kidney function; thus, the lack of association with BUN may reflect in part BUN’s low specificity for kidney function [36]. Third, the cohort design is susceptible to confounding. We minimized confounding by comparing VN + PT to VN + CP, which is given for the same indication. We controlled for an extensive set of covariates and showed that our results were minimally changed by propensity score trimming, suggesting that confounding from propensity score misspecification is minimal. Further, because risk factors for mortality and AKI overlap substantially, and differences in effectiveness between PT and CP are unlikely [3] mortality can be viewed as a negative control outcome [50]. Thus, our finding of a significant crude association between VN + PT and mortality that was nearly completely nullified in weighted analysis suggests that confounding was minimized. Fourth, there were missing data. We minimized missing data bias with multiple imputation, which allowed us to control for additional covariates such as albumin, lactate, and bilirubin that have generally been unaccounted for in studies of VN + PT and AKI. Fifth, we were unable to account for potential dilutional effects of fluid resuscitation. However, such dilution would be expected to impact creatinine, Cys-C, and BUN similarly. Sixth, we did not have urine output data (UOP). However, UOP data are often incomplete, and are susceptible to ascertainment bias, wherein UOP data are more often complete in patients with urinary catheters, which are typically placed in patients with high severity of illness. Seventh, given the low dialysis rate, our study was underpowered for this endpoint. Lastly, we included critically ill patients enrolled at a single center, which may limit generalizability. However, our replication of associations between VN + PT and creatinine suggest that our findings are not unique to our population.

Conclusions

VN + PT was associated with an increased risk of creatinine-defined AKI, but not changes in alternative kidney function biomarkers or clinical outcomes downstream from true AKI, supporting the hypothesis that creatinine-defined AKI during VN + PT may represent pseudotoxicity.

References

Goodman KE, Cosgrove SE, Pineles L et al (2021) Significant regional differences in antibiotic use across 576 US hospitals and 11 701 326 adult admissions, 2016–2017. Clin Infect Dis 73:213–222. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa570

Kimball JM, Deri CR, Nesbitt WJ, Nelson GE, Staub MB (2021) Development of the three antimicrobial stewardship E’s (TASE) framework and association between stewardship interventions and intended results analysis to identify key facility-specific interventions and strategies for successful antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 73:1397–1403. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab430

Watkins RR, Deresinski S (2017) Increasing evidence of the nephrotoxicity of piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin combination therapy—what is the clinician to do? Clin Infect Dis 65:2137–2143. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix675

Bellos I, Karageorgiou V, Pergialiotis V, Perrea DN (2020) Acute kidney injury following the concurrent administration of antipseudomonal β-lactams and vancomycin: a network meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 26:696–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.019

Filippone EJ, Kraft WK, Farber JL (2017) The nephrotoxicity of vancomycin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 102:459–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.726

Luque Y, Louis K, Jouanneau C et al (2017) Vancomycin-associated cast nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28:1723–1728. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016080867

Pill MW, O’Neill CV, Chapman MM, Singh AK (1997) Suspected acute interstitial nephritis induced by piperacillin–tazobactam. Pharmacotherapy 17:166–169

Pais GM, Liu J, Avedissian SN et al (2020) Lack of synergistic nephrotoxicity between vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam in a rat model and a confirmatory cellular model. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:1228–1236. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz563

He M, Souza E, Matvekas A, Crass RL, Pai MP (2021) Alteration in acute kidney injury potential with the combination of vancomycin and imipenem-cilastatin/relebactam or piperacillin/tazobactam in a preclinical model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e02141-e2220. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02141-20

Chang J, Pais G, Valdez K, Marianski S, Barreto EF, Scheetz MH. Glomerular function and urinary biomarker changes between vancomycin and vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam in a translational rat model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022:aac0213221. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.02132-21 (Epub ahead of print)

Avedissian SN, Pais GM, Liu J, Rhodes NJ, Scheetz MH (2020) piperacillin–tazobactam added to vancomycin increases risk for acute kidney injury: fact or fiction? Clin Infect Dis 71:426–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz1189

Bauer JH, Brooks CS, Burch RN (1982) Clinical appraisal of creatinine clearance as a measurement of glomerular filtration rate. Am J Kidney Dis 2:337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(82)80091-7

Landersdorfer CB, Kirkpatrick CM, Kinzig M, Bulitta JB, Holzgrabe U, Sörgel F (2008) Inhibition of flucloxacillin tubular renal secretion by piperacillin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 66:648–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03266.x

Wen S, Wang C, Duan Y et al (2018) OAT1 and OAT3 also mediate the drug-drug interaction between piperacillin and tazobactam. Int J Pharm 537:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.037

Sokol PP (1991) Mechanism of vancomycin transport in the kidney: studies in rabbit renal brush border and basolateral membrane vesicles. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 259:1283–1287

Wen S, Wang C, Huo X et al (2018) JBP485 attenuates vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity by regulating the expressions of organic anion transporter (Oat) 1, Oat3, organic cation transporter 2 (Oct2), multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (Mrp2) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in rats. Toxicol Lett 295:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.06.1220

Vallon V, Eraly SA, Rao SR et al (2012) A role for the organic anion transporter OAT3 in renal creatinine secretion in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302:F1293–F1299. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00013.2012

Dong J, Liu Y, Li L, Ding Y, Qian J, Jiao Z. Interactions between meropenem and renal drug transporters. Curr Drug Metab. 2022. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200223666220428081109 (Epub ahead of print)

Velez JCQ, Obadan NO, Kaushal A, Alzubaidi M, Bhasin B, Sachdev SH, Karakala N, Arthur JM, Nesbit RM, Phadke GM (2018) Vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury with a steep rise in serum creatinine. Nephron 139(2):131–142. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487149

Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR (2012) Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Kidney Int 81:442–448. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.379

Odutayo A, Wong CX, Farkouh M et al (2017) AKI and long-term risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 28:377–387. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016010105

Fugate JE, Kalimullah EA, Hocker SE, Clark SL, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA (2013) Cefepime neurotoxicity in the intensive care unit: a cause of severe, underappreciated encephalopathy. Crit Care 17:R264. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13094

Lee JD, Heintz BH, Mosher HJ, Livorsi DJ, Egge JA, Lund BC (2021) Risk of acute kidney injury and clostridioides difficile infection with piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, and meropenem with or without vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis 73:e1579–e1586. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1902

Sandiumenge A, Diaz E, Rodriguez A et al (2006) Impact of diversity of antibiotic use on the development of antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 57:1197–1204. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkl097

Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R (2010) Cystatin C in acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Crit Care 16(6):533–539

Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H et al (2012) Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367:20–29. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1114248

Miano TA, Meyer NJ, Hennessy S et al (2021) Combined vancomycin and piperacillin–tazobactam treatment is not associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) when assessed using plasma cystatin C. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 203:A1017

Reilly JP, Wang F, Jones TK et al (2018) Plasma angiopoietin-2 as a potential causal marker in sepsis-associated ARDS development: evidence from Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis. Intensive Care Med 44:1849–1858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5328-0

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC et al (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med 31(4):1250–1256. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B

Blair M, Côté JM, Cotter A, Lynch B, Redahan L, Murray PT (2021) Nephrotoxicity from vancomycin combined with piperacillin–tazobactam: a comprehensive review. Am J Nephrol 52(2):85–97. https://doi.org/10.1159/000513742

Navalkele B, Pogue JM, Karino S, Nishan B, Salim M, Solanki S, Pervaiz A, Tashtoush N, Shaikh H, Koppula S, Koons J, Hussain T, Perry W, Evans R, Martin ET, Mynatt RP, Murray KP, Rybak MJ, Kaye KS (2017) Risk of acute kidney injury in patients on concomitant vancomycin and piperacillin–tazobactam compared to those on vancomycin and cefepime. Clin Infect Dis 64(2):116–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw709

Siew ED, Ikizler TA, Matheny ME et al (2012) Estimating baseline kidney function in hospitalized patients with impaired kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7:712–719. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10821011

Herget-Rosenthal S, Marggraf G, Hüsing J, Göring F, Pietruck F, Janssen O, Philipp T, Kribben A (2004) Early detection of acute renal failure by serum cystatin C. Kidney Int 66(3):1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00861.x

Nejat M, Pickering JW, Walker RJ, Endre ZH (2010) Rapid detection of acute kidney injury by plasma cystatin C in the intensive care unit. Nephrol Dial Transpl 25:3283–3289. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfq176

Dabitao D, Margolick JB, Lopez J, Bream JH (2011) Multiplex measurement of proinflammatory cytokines in human serum: comparison of the Meso Scale Discovery electrochemiluminescence assay and the Cytometric Bead Array. J Immunol Methods 372:71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2011.06.033

Griffin BR, Faubel S, Edelstein CL (2019) Biomarkers of drug-induced kidney toxicity. Ther Drug Monit 41:213–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/FTD.0000000000000589

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.2

Neyra JA, Leaf DE (2018) Risk prediction models for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: opus in progressu. Nephron 140:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490119

Cartin-Ceba R, Kashiouris M, Plataki M, Kor DJ, Gajic O, Casey ET (2012) Risk factors for development of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Care Res Pract 2012:691013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/691013

Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T et al (2009) Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int 75:652–660. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2008.638

Austin PC (2009) Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput 38:1228–1234. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610910902859574

Granger E, Sergeant JC, Lunt M (2019) Avoiding pitfalls when combining multiple imputation and propensity scores. Stat Med 38:5120–5132. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8355

Tennant PWG, Arnold KF, Ellison GTH, Gilthorpe MS (2021) Analyses of “change scores” do not estimate causal effects in observational data. Int J Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab050

Stürmer T, Webster-Clark M, Lund JL et al (2021) Propensity score weighting and trimming strategies for reducing variance and bias of treatment effect estimates: a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol 190:1659–1670. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab041

Schreier DJ, Kashani KB, Sakhuja A et al (2019) Incidence of acute kidney injury among critically ill patients with brief empiric use of antipseudomonal β-lactams with vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis 68:1456–1462. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy724

Buckley MS, Komerdelj IA, D'Alessio PA, et al. Vancomycin with concomitant piperacillin/tazobactam vs. cefepime or meropenem associated acute kidney injury in the critically ill: a multicenter propensity score-matched study. J Crit Care. 2022;67:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.10.018.

Blevins AM, Lashinsky JN, McCammon C, Kollef M, Micek S, Juang P (2019) Incidence of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients receiving vancomycin with concomitant piperacillin–tazobactam, cefepime, or meropenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e02658-e2718. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02658-18

Côté JM, Desjardins M, Cailhier JF, Murray PT, Beaubien SW (2022) Risk of acute kidney injury associated with anti-pseudomonal and anti-MRSA antibiotic strategies in critically ill patients. PLoS ONE 17(3):e0264281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264281

Kane-Gill SL, Ostermann M, Shi J, Joyce EL, Kellum JA (2019) Evaluating renal stress using pharmacokinetic urinary biomarker data in critically ill patients receiving vancomycin and/or piperacillin–tazobactam: a secondary analysis of the multicenter sapphire study. Drug Saf 42:1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-019-00846-x

Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T (2010) Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 21:383–388. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61eeb

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (S10OD025172), NIDDK (K08DK124658, R01DK111638, R01DK113191, P30DK079310), NHLBI (R01HL137006, R01HL137915, K24HL155804, R01HL155159), and AHRQ (R01HS027626).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TAM had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: TAM, MGSS, NJM, SH. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: TAM, SH, WY, TGD, ARW, OO, RSA, APT, CAGI, BJA, FPW, RT, JPR, HMG, CVC, TKJ, NJM, MGSS. Drafting of the manuscript: TAM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: TAM, SH, WY, TGD, ARW, OO, RSA, APT, CAGI, BJA, FPW, RT, JPR, HMG, CVC, TKJ, NJM, MGSS. Manuscript approval: All authors gave final approval of this version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

FPW received research funding from Boeringher-Ingelheim, Astrazeneca, Vifor pharmaceuticals, and Whoop, Inc. SH leads a research and training center that receives educational funding from Pfizer Inc. MJM received research funding to her institution from Athersys, Inc, Biomarck Inc, and Quantum Leap Healthcare Collaborative for work unrelated to this manuscript. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Role of the funder/sponsor

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval

Subjects are enrolled with a waiver of timely informed consent with approval of the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Pennsylvania (IRB #808542). Subjects or their surrogates are approached as soon as possible for consent, and if consent is not obtained, all biospecimens and data are discarded.

Consent to participate

Subjects are enrolled with a waiver of timely informed consent with approval of the IRB of the University of Pennsylvania (IRB #808542). Subjects or their surrogates are approached as soon as possible for consent, and if consent is not obtained, all biospecimens and data are discarded.

Consent to publish

Not applicable/all data used for the present study have been anonymized, and the submission does not include information that may identify individual persons.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miano, T.A., Hennessy, S., Yang, W. et al. Association of vancomycin plus piperacillin–tazobactam with early changes in creatinine versus cystatin C in critically ill adults: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 48, 1144–1155 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06811-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06811-0