Abstract

This paper uses microdata to evaluate the impact on the steady-state unemployment rate of an increase in maximum benefit duration. We evaluate a policy change in Austria that extended maximum benefit duration and use this policy change to estimate the causal impact of benefit duration on labor market flows. We find that the policy change leads to a significant increase in the steady-state unemployment rate and, surprisingly, most of this increase is due to an increase in the inflow into rather than the outflow from unemployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are cross-country studies that relate aggregate parameters of the unemployment insurance system—i.e. average replacement rate and average benefit duration—and other labor market institutions in various countries to the aggregate unemployment rates in these countries. See for an overview Layard and Nickell (1999).

Note that Lalive and Zweimüller (2004a, b) also use Austrian data to analyze how unemployment benefits affect the outflow from unemployment but these studies are based on information from Austrian regions with a dominant steel industry. In these regions, in 1988 an extended benefit program was introduced for workers aged 50 or older. The focus of both studies is on policy endogeneity, which indeed turns out to introduce a substantial bias in the parameter estimates. In Lalive et al. (2006) and the current paper to avoid policy endogeneity problems the analysis excludes the steel dominated regions.

Note, however, that according to Fredriksson and Holmlund (2006) there is not much empirical evidence in support of such an effect.

Note that there is no theoretical explanation for the existence of end-of-benefit spikes. It could be that the spikes have to do with strategic timing of the job starting date, i.e. workers have already found a job but they postpone starting to work until their benefits are close to expiration. Card and Levine (2000) point at the possibility that there is an implicit contract between the unemployed worker and his previous employer to be rehired just before benefit expire.

The regional extended benefit program was implemented in 1987 and ended in 1993 and was directed to a subset of Austrian regions. (See Winter-Ebmer 1998, 2003 and Lalive and Zweimüller 2004a, b). The policy change analyzed here applies to workers in all other regions and excludes regions that were subject to the regional extended benefit program.

This so-called “Notstandshilfe” implies that job seekers who do not meet benefit eligibility criteria can apply at the beginning of their spell.

See Nickell and Layard (1999). It is interesting to note that the incidence of long-term unemployment in Austria is closer to U.S. figures than to those of other European countries. In 1995, when our sample period ends, 17.4% of the unemployment stock were spells with an elapsed duration of 12 months or more. This compares to 9.7% for the U.S. and to 45.6% for France, 48.3% for Germany, and 62.7% for Italy (OECD 1999).

UB duration was 20 weeks for job-seekers who did not meet this requirement. This paper focuses on individuals who were entitled to at least 30 weeks of benefits.

This so-called Krisenregionsregelung applied to about 15% of all observations. In these crises- ridden regions even more generous unemployed insurance policies were implemented between 1988 and 1993. For empirical analyzes of these programs, see Winter-Ebmer (1998, 2003) and Lalive and Zweimüller (2004a, b).

The higher fraction of ages 50 + is because the big birth cohorts of 1940–1942 are in the age group 40–49 in the before-policy sample whereas they are in the age group 50 + in the after-policy sample. The higher fraction of females in the after-policy sample is most likely due to the fact that the cohorts that are in the after-policy but not in the before-policy sample have a high labor force participation and are relatively large (vintages in the mid 1950s). In contrast, the cohorts that are in the before-policy sample but not in the after-policy sample (vintages of the early 1930s) do have a low labor force participation and are comparably small.

All observations in our samples for which both T39 i = 0 and T52 i = 0 are eligible for at most 30 weeks of benefits.

The vector of individual characteristics includes the individual’s age, age dummies, dummies for the inflow quarter, log daily wage, experience, tenure, broad occupation (blue/white collar), sex, and industry (manufacturing, construction/tourism, other industries).

The analysis below will be undertaken also for more flexible specifications of age and calendar time, and will be estimated for various subgroups to assess the robustness of the results.

If policy was implemented because policy makers became concerned with worse labor market prospects for older individuals there would be policy endogeneity.

With respect to the effect of PBD on the unemployment outflow, our results are in line with the estimates in Lalive et al. (2006) who find that the increase in PBD from 30 to 52 weeks lead to an increase in the expected duration of unemployment of 12.3% and who find a very small effect of the increase in PBD from 30 to 39 weeks. Our results are also similar to previous estimate to Winter-Ebmer (2003) who finds substantial effects of PBD on the unemployment inflow for a different policy change in Austria, which extended PBD for older worker in certain regions.

Note that this result is very much in line with our earlier results on the effects of PBD extensions in Austria (Lalive et al. 2006) suggesting that extending PBD from 30 to 52 weeks increases unemployment duration by 2.27 weeks which is about 12% of average unemployment duration.

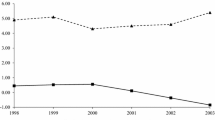

As indicated before, our sample contains attached workers for which the unemployment rate is rather low. For example, in the third quarter of 1988 the average unemployment rate in our sample was 2.04%.

Note that the outflow result is, again, very much in line with our earlier result for Austria (Lalive et al. 2006) suggesting that extending PBD from 30 to 39 weeks increases unemployment duration by 0.45 weeks which is about 2% of average unemployment duration.

Note that in the simulations we use all estimated parameters of Table 6 irrespective of whether or not they are significantly different from zero at conventional levels of significance.

References

Adamchik V (1999) The effect of unemployment benefits on the probability of re-employment in Poland. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 61(1):95–108

Addison JT, Portugal P (2004) How does the unemployment insurance system shape the time profile of jobless duration? Econ Lett 85(2):299–234

Anderson PM, Meyer BD (1997) Unemployment insurance takeup rates and the after-tax value of benefits. Q J Econ 112(3):913–937

Card DE, Levine PB (2000) Extended benefits and the duration of UI spells: evidence from the New Jersey extended benefit program. J Public Econ 78(1–2):107–138

Carling K, Edin P-A, Harkman A, Holmlund B (1996) Unemployment duration, unemployment benefits, and labor market programs in Sweden. J Public Econ 59(3):313–334

Christofides LM, McKenna CJ (1995) Unemployment insurance and moral hazard in employment. Econ Lett 49(2):205–210

Christofides LM, McKenna CJ (1996) Unemployment insurance and job duration in Canada. J Labor Econ 14(2):286–312

Fredriksson P, Holmlund B (2003) Improving incentives in unemployment insurance: a review of recent research, IFAU working paper No.5

Fredriksson P, Holmlund B (2006) Improving incentives in unemployment insurance: a review of recent research. J Econ Surv 20(3):357–386

Green DA, Riddell WC (1997) Qualifying for unemployment insurance: an empirical analysis. Econ J 107(440):67–84

Green DA, Sargent TC (1998) Unemployment insurance and job durations: seasonal and non-seasonal jobs. Can J Econ 31(2):247–278

Grossman JB (1989) The work disincentive effect of extended unemployment compensation: recent evidence. Rev Econ Stat 71(1):159–164

Ham J, Rea S (1987) Unemployment insurance and male unemployment duration in Canada. J Labor Econ 5:325–353

Hunt J (1995) The effect of unemployment compensation on unemployment duration in Germany. J Labor Econ 13(1):88–120

Katz L, Meyer B (1990) The impact of the potential duration of unemployment benefits on the duration of unemployment. J Public Econ 41(1):45–72

Lalive R, Zweimüller J (2004a) Benefit entitlement and the labor market: evidence from a large-scale policy change. In: Agell J, Keene M, Weichenrieder A (eds) Labor market institutions and public policy 2003. MIT, Cambridge, pp 63–100

Lalive R, Zweimüller J (2004b) Benefit entitlement and unemployment duration: the role of policy endogeneity. J Public Econ 88(12):2587–2616

Lalive R, van Ours JC, Zweimüller J (2006) How changes in financial incentives affect the duration of unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 73(4):1009–1038

Layard R, Nickell S (1999) Labor market institutions and economic performance. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol. 3C, pp 3029–3084

Meyer BD (1990) Unemployment insurance and unemployment spells. Econometrica 58(4):757–782

Moffitt R (1985) Unemployment insurance and the distribution of unemployment spells. J Econom 28(1):85–101

Moffitt R, Nicholson W (1982) The effect of unemployment insurance on unemployment: the case of federal supplemental benefits. Rev Econ Stat 64(1):1–11

Mortensen DT (1977) Unemployment insurance and job search decisions. Ind Labor Relat Rev 30(4):505–517

Mortensen DT, Pissarides CA (1994) Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 61(3):397–415

Nickell S, Layard R (1999) Labor market institutions and economic Performance. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 3029–3084

OECD (1999) Benefit systems and work incentives, Paris

Pissarides CA (2000) Equilibrium unemployment theory, 2nd edn. MIT, Cambridge

Puhani PA (2000) Poland on the dole: the effect of reducing the unemployment benefit entitlement period during transition. J Popul Econ 13(1):35–44

Roed K, Zhang T (2003) Does unemployment compensation affect unemployment duration? Econ J 113(484):190–206

Van Ours JC, Vodopivec M (2006) How shortening the potential duration of unemployment benefits entitlement affects the duration of unemployment: evidence from a natural experiment. J Labor Econ 24(2):351–378

Winter-Ebmer R (1998) Potential unemployment benefit duration and spell length: lessons from a quasi-experiment in Austria. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 60(1):33–45

Winter-Ebmer R (2003) Benefit duration and unemployment entry: a quasi-experimental evidence for Austria. Eur Econ Rev 47(2):259–273

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor, Christian Dustmann, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. Andreas Steinhauer and Oliver Ruf did excellent research assistance. Financial support by the Austrian Science Fund (National Research Network S103: “The Austrian Center for Labor Economics and the Analysis of the Welfare State”) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Christian Dustmann

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lalive, R., van Ours, J.C. & Zweimüller, J. Equilibrium unemployment and the duration of unemployment benefits. J Popul Econ 24, 1385–1409 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0318-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0318-8