Abstract

We investigate the determinants of the support for cannabis legalization finding a causal effect of personal experience with cannabis use. Current and past cannabis users are more in favor of legalization. We relate this finding to self-interest and inside information about potential dangers of cannabis. While the self-interest effect is not very surprising, the effect of inside information suggests that cannabis use is not as harmful as cannabis users originally thought it was before they started consuming. Our analysis suggests that as the share of cannabis users in the population increases, support for cannabis legalization will also increase.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In many countries the production, use and distribution of cannabis are prohibited. However, the legal framework on cannabis is changing as some countries are becoming more tolerant. The Netherlands quasi-legalized cannabis use through the introduction of “coffeeshops” which are licensed cannabis sales outlets. Recently, four states in the USA—Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington—legalized cannabis for personal use. A licensed retail and production system for cannabis was introduced in Uruguay in 2014. There are several alternatives to prohibition varying from decriminalization to regulation and legalization (European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction 2013). Whereas decriminalization refers to the removal of the criminal status for personal possession or use, regulation refers to limits on access and restrictions on advertizing. Legalization refers to cannabis use and cannabis supply, making lawful what previously was prohibited. Although in the policy debate a distinction is made between legalization and regulation of cannabis, we consider regulation as legalization under restrictions and focus on the dichotomy between prohibition and legalization.Footnote 1

In the policy debate on cannabis legalization, there are frequent references to studies which find that cannabis use has adverse effects on physical and mental health as well as other negative effects on important life outcomes such as educational attainment and labor market position (Ellickson et al. 1999; Brook et al. 1999; French et al. 2001; Arseneault et al. 2004; Van Ours 2006, 2007; Van Ours et al. 2013). There are also frequent references to harm to society through crime and anti-social behavior of users, the impacts on drug tourism and the gateway hypothesis.Footnote 2 Nevertheless, in their overview study on the effects of cannabis use, Van Ours and Williams (2015) conclude that there do not appear to be serious harmful health effects of moderate cannabis use but there is evidence of reduced mental well-being for heavy users who are susceptible to mental health problems. Furthermore, they conclude that while there is robust evidence that early cannabis use reduces educational attainment, there remains substantial uncertainty as to whether using cannabis has adverse labor market effects. Negative effects of cannabis use seem to be related to a small group of users while for the majority of cannabis users these effects are absent.

It is well-known that cannabis users are more in favor of legalization than non-users. A 1989 study from Norway shows that 65 % of cannabis users were in favor of prohibition of cannabis while among non-users this was 95 % (Skretting 1993). This study also finds that those who use cannabis do not consider drug possession as a serious crime possibly because of self-interest.Footnote 3 Trevino and Richard (2002) finds that drug users in Houston have different attitudes toward drug policies than non-drug users; 68 % of drug users were in favor of legalizing cannabis, while only 33 % of the non-drug users were in favor. In the Netherlands, in 2008, among cannabis users only 7 % was in favor of prohibition of cannabis, while this was 50 % among non-users (Van der Sar et al. 2011). In Australia, in 1998, 57 % of cannabis users were in favor of legalizing cannabis while among the non-users this was only 18 % (Williams et al. 2016).

All in all, several studies suggest that support for cannabis legalization is higher among cannabis users. Interesting as this may be in itself, the fact that cannabis users are more in favor of legalizing cannabis does not necessarily imply that opinions are influenced by cannabis use in a causal way. It could be that individuals who are more likely to consume cannabis are also more in favor of legalization without personal experience affecting opinions. Knowing whether or not there is a causal effect from cannabis use to opinions is interesting because if there is a causal effect, this reveals how potential dangers of cannabis use are assessed. Cannabis users may change their mind about cannabis legalization through personal experience. As Orphanides and Zervos (1995) point out there is uncertainty about whether or not individuals might get addicted if they start using drugs. Individuals may start using cannabis by way of experimenting balancing the instant pleasure it provides and probabilistic future harm. Consumption of cannabis is not equally harmful to all. Some may not be susceptible to addiction while others are of the addictive type. Individuals do not know their addictive tendency and the only way to find out is by experimentation. However, if individuals of the addictive type experiment and recognize their tendency too late they are drawn into addiction. If individuals believe that their risk of addiction is high they may optimally choose not to experiment with cannabis. Once individuals experiment with cannabis they may conclude that they are not of the addictive type and for them there is no harm. In other words, by using cannabis individuals learn about potential harmful effects and therefore they may change their mind about legalization.

We argue that if cannabis use has a favorable effect on opinions about cannabis legalization, then this may reveal that cannabis use is not as harmful as what it is originally believed. However, such a causal effect may also have to do with self-interest, i.e. cannabis legalization leading to easier access to cannabis and perhaps lower prices. We argue that it is possible to make a distinction between inside information and self-interest by comparing how past cannabis use and current cannabis use affect opinions. Whereas the effect of current cannabis use may be a mixture of self-interest and inside information, the effect of past cannabis use is related to inside information only. Although previous studies clearly show that there is a significant difference between cannabis users and non-users in the opinions about cannabis policies, they do not establish whether this has to do with a causal relationship. The only study that establishes a causal relationship between user status and opinions on cannabis policy is Williams et al. (2016). They analyze Australian data from cross-sectional surveys over the period 1993–2007 using a quasi-panel approach to account for potential endogeneity of cannabis use. The main conclusion is that preference of past users for legalization is consistent with information on net benefits of cannabis use while self-interest as contributing to current users’ support for legalization cannot be ruled out. Although focusing on a similar research question, our study differs from theirs in terms of econometric specification and identification strategy.

In the empirical part of our analysis, we use a statistical model that allows us to establish the causal effects of cannabis use on opinions about cannabis policies. We focus on two policy statements in a survey conducted in the Netherlands in 2008. Individuals were asked to indicate their support for statements on prohibition and legalization of cannabis. We estimate simultaneous models that integrate cannabis use dynamics and opinions on cannabis use.Footnote 4 We find that cannabis user status is correlated with opinions on cannabis legalization. This correlation partly reflects a causal effect. Current cannabis users and past cannabis users seem to have learned from their experiences and are therefore more in favor of legalizing cannabis. Current cannabis users are more in favor of legalizing cannabis than past cannabis users. This suggests that self-interest plays a role in opinions about cannabis policies but more interestingly, it also suggests that cannabis use may not be as harmful as non-users are inclined to think.Footnote 5

Our contribution to the literature on the economics of cannabis use is threefold. First, we present an analysis of opinions on cannabis policies in a quasi-legal environment. The Dutch respondents have little incentive to misreport as there is nothing illegal about using cannabis. Because of the quasi-legal environment, they are also familiar with potential consequences of making cannabis easily available. Second, we establish a causal link from cannabis use to opinions on cannabis policy. Third, we present a novel strategy to investigate the assessment of potential harmful effects by distinguishing between self-interest and inside information. Since several aspects of cannabis use feed into opinions on cannabis policies, these harmful effects are not only related to the individuals themselves but also to the society in general.

The setup of our paper is as follows. In Sect. 2 we give a brief overview of cannabis policy in the Netherlands. In Sect. 3 we discuss our data and give some stylized facts. Section 4 presents our empirical model and in Sect. 5 we discuss our baseline parameter estimates together with estimates from several sensitivity and falsification/placebo analysis. Section 6 concludes.

2 Cannabis policy in The Netherlands

As indicated in the introduction, in the Netherlands, cannabis use is quasi-legalized. Small quantities of cannabis can be bought in cannabis shops. These are retail outlets and referred to as “coffeeshops”. Cannabis policy is focused on health issues (De Graaf et al. 2010) and can be summarized as tolerant (Van Solinge 1999). The basic aim of the cannabis policy is to lessen the potential harm to users and their environment. Although cannabis is tolerated by Dutch authorities, use of hard drugs and production and trade of soft drugs and hard drugs are classified as serious offenses (Palali and van Ours 2015). The distinction between soft and hard drugs in terms of legal measures is at the heart of drug policy. The intention is to provide an organized environment for cannabis sale, thus keeping potential customers away from dealers of more harmful illicit drugs and having a control over the quality of cannabis. Coffeeshops are regulated by law. Some of the fundamental rules are: no sale of hard drugs, no advertising, no sale to youngsters below 18 years of age, no nuisance and no more than 500 g of cannabis on the premises. Failures to operate within the regulations might result in shutting down of the shop. The duration of shut down depends on the seriousness of the violations committed by the owners of coffeeshops.

The 1980s stand as a crucial period in the history of Dutch cannabis policies. In 1980, the policy of tolerance of coffeeshops was publicly announced by Dutch authorities and this announcement was followed by a sharp increase in the number of coffeeshops (Jansen 1991). In the mid 1990s there were around 1500 coffeeshops. However, in the 1990s the tolerant cannabis policy was increasingly criticized from inside the country as well as from other countries. In 1995, the Dutch government made changes in the rules under which coffeeshops could operate. From 1996 onwards the limit for personal possession of cannabis was decreased from 30 to 5 g. Moreover, the monitoring and punishment of production and trade of cannabis were increased and more importantly, local governments were given the opportunity to decide whether or not they wanted to have a cannabis-shop in their municipality. These policies caused a substantial decrease in the number of coffeeshops (Bieleman et al. 2007). In 1999, there were 846 coffeeshops across the Netherlands, a number that went down to 651 in 2011 and further down to 582 in 2015.

3 Data and stylized facts

3.1 Data

Our data are from the 2008 Alcohol and Drugs study, one of the assembled studies of the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS) panel. The LISS survey is administered by CentERdata, a research institute of Tilburg University. The data used in our study are from one of the special cross-sectional surveys conducted in November 2008. The online survey is addressed to a representative Dutch sample. Respondents answered various questions about their opinions on different types of government policies on cannabis. Furthermore, respondents were asked whether they had ever used cannabis and if they answered affirmatively they were faced with the question: At what age, approximately, did you first use cannabis? Individuals were also asked to report if they were currently using cannabis, i.e. whether they had used cannabis in the previous 30 days. Because older individuals were never confronted with cannabis supply, we perform our analysis on individuals who were born in 1960 or later. It appears that about 20 % of the respondents ever used cannabis whereas less than 5 % used cannabis in the previous 30 days. The latter are considered to be current users whereas the others are considered to be past users.

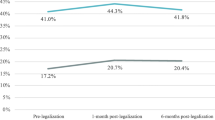

We use information on past cannabis use and current cannabis use, together with the retrospective question on the age of first cannabis use to analyze cannabis use dynamics. Figure 1 shows the dynamics in cannabis use. Panel a shows that the starting rate for cannabis use has a peak at age 17. The probability to use cannabis for the first time is at its highest point at age of 17. There are other smaller peaks at age 19 and 21. After age 25 the probability of using cannabis conditional on not using before virtually becomes zero. Panel b confirms this finding by showing that the slope of the line representing the cumulative probability of using cannabis becomes very small after age 25.

3.2 Stylized facts

In the main part of our empirical analysis, we focus on two statements. The respondents were asked to indicate their opinion on a scale from 1 to 5 ranging from definitely disagree to definitely agree with the following statement: cannabis should be prohibited. We rescaled the responses given to this statement assuming that those who indicated to agree with it would disagree with the statement that cannabis should be legalized and vice versa. The respondents were also asked to report their opinion on the statement coffeeshops should be allowed to sell cannabis. We assume that this statement on coffeeshops is equivalent to a statement on the current status of cannabis policy in the Netherlands. Panels a and b of Table 1 present the distribution of opinions for the full sample and subsamples distinguished by user status. On average, the responses are evenly distributed; 45 % of the sample agree that cannabis should be legalized whereas another 34 % state that they disagree. The remaining 21 % is indifferent. Similarly, 46 % of the individuals state that they agree with the idea of selling cannabis through coffeeshops whereas 35 % disagree.Footnote 6

Dividing the sample into three categories based on user status exhibits interesting results. Among current cannabis users only 1 definitely disagree and 2 legalized whereas 89 percent agrees. Similarly 85 % of the current users of cannabis agree with the statement that coffeeshops should be allowed to sell cannabis. These percentages are different for past users of cannabis of whom 77 % disagree with prohibition whereas 9 % agree with this idea. Similarly 74 % of the past cannabis users agree with the statement that coffeeshops should be allowed sell cannabis. The numbers are reversed for those who have never used cannabis in their lives. Almost half of the never users state that they disagree with the idea of legalization whereas only 31 % of the never users agree. Among the never users only 32 % agree with coffeeshops while 45 % of these respondents disagree.

The last column in Table 1 presents the p values of a Chi-square test where we test if the differences between reported percentages among current, past and never users are statistically significant as compared to never users, never users and ever users respectively. For most of the policy statements, which will be discussed in more detail below, the raw data indicate that there are significant differences in opinions about cannabis policies depending on the user status.

Table 2 provides a description and summary statistics of the variables used in our analysis. Most of the descriptions are self-explanatory. For the question on political preferences we grouped the various parties in the Netherlands as follows: Conservatives (VVD, Trots op Nederland, PVV), Left wing (PvdA, SP, Groen-Links, D66, Partij van de Dieren), Center (CDA, Christenunie, SGP), Others (other party, would rather not say, would not vote, is not entitled to vote, blank vote, does not know).

4 Empirical model

4.1 Cannabis use dynamics

In the analysis of cannabis use starting rates, we assume that individuals become vulnerable to the risk of cannabis use from age 13 onwards. This is because only a few individuals start using cannabis before the age of 13. We specify the starting rate for cannabis use at time t (\(t = 0\) at age 12) conditional on observed characteristics x and unobserved characteristics u as

where \(\beta _c\) represent the effects of independent variables and \(\lambda _c (t)\) represents individual duration (age) dependence. Unobserved heterogeneity, in this case, is denoted with u which controls for differences in individuals’ unobserved susceptibility to cannabis use. We model duration (age) dependence in a flexible way by using a step function \(\lambda _c(t)=\exp (\varSigma _{k}\lambda _{k}I_{k}(t))\), where \(k (= 1,\ldots ,9)\) is a subscript for age categories and \(I_{k}(t)\) are time-varying dummy variables that are one in subsequent categories, 8 of which are for individual ages (age \(13,\ldots ,20\)) and the last interval is for ages above 20 years. Because we also estimate a constant term, we normalize \(\lambda _{c,1}=0\).

The conditional density function of the completed durations until the uptake of cannabis use can be written as

We integrate out the unobserved heterogeneity such that density function for the duration of time until cannabis uptake t conditional on x is

where G(u) is assumed to be a discrete mixing distribution with 2 points of support \(u_a\) and \(u_b\) reflecting the presence of two types of individuals in the hazard rate for cannabis uptake. The associated probabilities are denoted as follows: \(\Pr (u = u_a) = r\) and \(\Pr (u = u_b + u_a) = 1-r\) with \(0\le r \le 1\), and r is modeled using a logit specification, \(r=\frac{\exp (\alpha )}{1+\exp (\alpha )}\).

To account for the discrete nature of the observations of age of onset of cannabis use, the log-likelihood is specified as

where i is an index for individual, n is the number of individuals in the sample and \(d_{c,i}\) is a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if an individual started using cannabis and equal to 0 if an individual did not start using cannabis before being interviewed at age \(t_{s}\).

In addition to starting rates of cannabis use, we also estimate quitting rates in order to have a complete analysis of cannabis use dynamics. The LISS panel includes questions on the last month use of cannabis. We assume that if the individual reports no use of cannabis in the last 30 days, that individual stopped using cannabis in time period starting from the first use of cannabis until 30 days prior to the survey. The conditional density function for the completed durations until the last use of cannabis can be written as

Even though we do not observe the exact time of quitting in terms of age of respondents, we can still analyze the duration of quitting thanks to the interval censored nature of the data. However, note that due to the uncertainty about the exact time of quitting, duration dependence is not estimated here. On the other hand it is certain that the duration of cannabis use, \(\tau \), will lie in the interval [\(0,\tau _q\)] where \(\tau _q\) is the difference between age at the time of survey and the age of the first use. This means that we can integrate out the conditional density function over this period to account for the uncertainty of quitting time and obtain the distribution function, \(F_q\). Individuals who report using cannabis in the last 30 days are assumed to be right censored in their quitting, i.e. as yet they did not quit. Since the quitting analysis is performed only on those who ever used cannabis there are no left censored individuals. As in the analysis of the uptake of cannabis, we assume that there are 2 unobserved heterogeneity groups where the probabilities are assumed to follow a logistic distribution. The log-likelihood is specified as

where m is the number of individuals that ever used cannabis and \(d_{q,i}\) is a dummy variable which has a value of 1 if the individual stopped using cannabis and a value of 0 if the individual did not stop using cannabis.

Finally, we allow for the possibility that conditional on the observed characteristics, the age of uptake and the duration of use cannabis uptake and cannabis quits are correlated through unobserved characteristics. The joint density of completed durations until the uptake of cannabis use and completed durations of cannabis use is specified as:

where G(u, v) is the joint distribution of unobserved heterogeneity which assume to be discrete with an unknown number of support points.

4.2 Opinions on cannabis policy

We first model the determinants of opinions on cannabis policy assuming that the dynamics in cannabis use are exogenous. Then we take possible correlation between the two processes into account. Individuals report their opinions on the relevant cannabis policy statements on a scale of 1–5, with 1 representing definitely disagree and 5 representing definitely agree. In order to exploit this ordinal character of the dependent variable, we use an ordered probit model with Heckman and Singer type discrete unobserved heterogeneity (Heckman and Singer 1984). The unobserved latent variable in the ordered response model is defined as

where \(c_c\) represent current cannabis use, \(c_p\) represents past cannabis use and \(\epsilon \) controls for discrete type of unobserved heterogeneity which is different from the error term e that represents the random error term. The parameters of interest in our study are \(\rho _c\) and \(\rho _p\) which measure the effect of current and past use of cannabis on the opinions about cannabis policy statements. Furthermore, \(\beta _p\) measures the effect of our control variables whose descriptions and summary statistics are provided in detail in Table 2. The observed responses on the cannabis policy statements in the data are, then, assumed to be

where \(\mu \)’s are to be estimated threshold parameters in the ordered choice models. Assuming that the error term e has a standard normal distribution, we can write the following probabilities for the ordered probit model conditional on observable and unobservable individual heterogeneityFootnote 7:

where \(\varPhi (.)\) is standard normal cdf. Unconditional probabilities, then, can be written as

where \(j\in \left\{ 1,2,3,4,5\right\} \), denoting ordered responses. \(G(\epsilon )\) is assumed to be a discrete mixing distribution with 2 points of support \(\epsilon _a\) and \(\epsilon _b\) indicating that conditional on observed characteristics there are 2 types of individuals in the ordered responses given to the policy statements. The associated probabilities are denoted as follows: \(\Pr (\epsilon = \epsilon _a) = p\) and \(\Pr (\epsilon = \epsilon _b + \epsilon _a) = 1-p\) with \(0\le p \le 1\), where p is modeled using a logit specification, \(p=\frac{\exp (\alpha )}{1+\exp (\alpha )}\).

There are a number of assumptions and normalizations which need to be made for model identification. First, we assume that mean and variance of the error term e in the latent equation are 0 and 1, respectively. Since we have heterogeneity specific constants in the model, we also set the first threshold parameter \(\mu _{1}\) to zero. The other threshold parameters are modeled in the following way in order to ensure that probabilities are positive and thresholds are ordered: \(\mu _{2}=\gamma _{1}^{2}, \mu _{3}=\mu _{2} + \gamma _{2}^{2}\) and \(\mu _{4}=\mu _{3} + \gamma _{3}^{2}\). Finally, we write the likelihood function of the ordered choice model as \(\prod _{N}\hbox {Prob}(y=j |x_3)\).

Until now, when estimating the ordered probit model for opinions, we assume that the decision to use cannabis is exogenous, i.e. independent from any factor that would affect the opinions about cannabis policies. However, it is possible that there are unobserved personal characteristics that affect both the decision to use cannabis and opinions about cannabis policies. If, for example, certain individuals have an inclination toward cannabis use due to some intrinsic factors that would also lead them to have positive attitudes toward liberal cannabis policies, then we might end up with significant parameter estimates for \(\rho _c\) and \(\rho _p\) even though there is no causal relationship. In order to control for correlation between unobserved characteristics and establish a causal effect, we jointly estimate the ordered probit model and the mixed proportional hazard models following a discrete factor approach. The joint density function of the completed duration of uptake of cannabis, the duration of cannabis use and opinions on cannabis use is specified as:

where \(G(v,w,\epsilon )\) is a discrete mixing distribution underlying unobserved heterogeneity affecting age of onset of cannabis use, duration of use and opinions about cannabis policies. This approach is introduced by Heckman and Singer (1984) in order to control for unobserved heterogeneity in hazard rates and used for example by Mroz (1999) to estimate the effects of dummy endogenous variables. The approach is equivalent to a correlated random effects model in which the main idea is that unobserved heterogeneity affecting opinions about cannabis policies and unobserved heterogeneity affecting cannabis use dynamics can be correlated, i.e. they come from a joint mixing distribution. The assumption on support points of this joint distribution defines the types of individuals regarding opinions and cannabis use. If, for example, conditional on observed characteristics there are two types of individuals in terms of uptake of cannabis and two types in terms of quitting cannabis, then there could be four types of individuals in terms of cannabis dynamics. If in addition to this conditional on unobserved characteristics there are two types of individuals in terms of opinions on cannabis policy, then there could be eight types of individuals in terms of cannabis dynamics and opinions on cannabis policy. However, it could also be that there are only two types of individuals in terms of cannabis dynamics: Individuals who are inclined to used cannabis and individuals who will never start using cannabis. If this is the case, then there could be four types of individuals: those who are more in favor of cannabis policies and more likely to use drugs, those who are less in favor of cannabis policies and more likely to use drugs, those who are more in favor of liberal drug policies and more likely to abstain from drugs, and those who are against liberal drug policies and more likely to abstain from drugs. Finally, if there is a perfect correlation between unobserved heterogeneity behind cannabis use dynamics and opinions, only the first and the last types are identified. An important advantage of using the functional form assumptions behind this approach is that identification is achieved without relying on exclusion restrictions which can be very challenging to find because cannabis use is likely to have the same determinants as opinions on cannabis policy.

5 Parameter estimates

5.1 Cannabis use dynamics

The parameter estimates of the various models are obtained through the method of maximum likelihood. The parameter estimates of the mixed proportional hazard models describing starting rates and quitting rates of cannabis use are presented in Table 3. The first column presents the results for the starting rates. The parameter estimate for female is found to be negative and significant. Thus, as in previous studies we find that on average females start using cannabis at a later age. Religiosity of the parents during the childhood of respondents is found to be significantly negative. So, as the parents are more religious, the age of initiation to cannabis use increases. Migrant status of the individual is found to be insignificant. Moreover, the degree of urbanization of the municipality has a significant effect on the uptake of cannabis indicating that individuals residing in highly urban areas start using cannabis at earlier ages. The most likely reasons are that cannabis happens to be more available and living styles of individuals might make them more vulnerable to the risk of cannabis use in highly urban regions. Educational attainment does not seem to affect the uptake of cannabis.Footnote 8 Finally, there is a clear cohort effect since age at the time of the survey is an important determinant of cannabis uptake. Older cohorts were less likely to start using cannabis. In line with Fig. 1, age dependency parameters indicate that there is a peak in the uptake of cannabis at age 17 and another peak at age 19. The mass point estimates of column 1 show that unobserved heterogeneity is indeed significant in the data at hand. The estimate of \(-1.25\) for \(\alpha \) implies that 22 % of the respondents have a high starting rate of cannabis use whereas 78 % of them have a substantially lower starting rate.

Column 2 of Table 3 presents the parameter estimates for quitting rates. We find that females are not only more likely to start using cannabis at later ages but they are also more likely to quit early. The parameter estimate for the first urbanization category is negative and significant, indicating that those who live in highly urban areas quit using cannabis later. Lower educated individuals have a smaller quit rate and individuals from the older birth cohorts have a smaller quit rate as well. Finally, we find that those who start using cannabis at a later age quit earlier, i.e. early starters quit late. Conditional on the observed characteristics we do not find evidence of the presence of unobserved heterogeneity in the quit rate. If we estimate a joint model of cannabis starting and cannabis quitting, we find that there is correlation between the two processes through unobserved heterogeneity. However, the second LR test reported at the bottom of the table compares the independent models of cannabis uptake and cannabis quits against the correlated model. As shown, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the two processes are independent.

5.2 Opinions on cannabis use: baseline parameter estimates

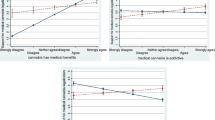

Table 4 presents our baseline parameter estimates for the first policy statement that cannabis should be legalized. The results for the univariate ordered probit model are shown in the first column. We find no evidence of unobserved heterogeneity having a significant effect. The parameter estimates of both past use and current use of cannabis are positive and significant indicating that both self-interest and information may have an effect on opinions. However, the estimates in the first column are based on the assumption that the decision to use cannabis is exogenous to the opinions regarding cannabis policies.

The correlated models whose parameter estimates are presented in the second column of Table 4 are obtained after controlling for possible endogeneity. Now, we are able to identify two mass-points in the ordered probit for opinions indicating that once we take correlation with cannabis use dynamics in account there is unobserved heterogeneity affecting opinions.Footnote 9 Clearly, the parameter estimates of cannabis use status become smaller in absolute terms indicating that part of the effects found in the univariate model are due to the correlated unobserved heterogeneity. The remaining effect may be interpreted as causal. The second LR test shows that past and current cannabis use have significant effects on opinion on cannabis legalization while the third LR test shows that the effect of past cannabis use is significantly smaller than the effect of current cannabis use. The opinions of current cannabis users are expected to be affected by both self-interest and information. The opinions of past cannabis users are not affected by self-interest. Parameter estimates reflect only the effect of information about cannabis use. The results obtained for past users indicate that cannabis may not be as harmful as individuals originally thought or as non-users are inclined to think. This may be specific to countries like the Netherlands where cannabis use is legalized or quasi-legalized.Footnote 10

Since the parameter estimate for current users is larger in absolute terms than the parameter estimate for past users there is also evidence of self-interest influencing opinions. Indeed likelihood ratio test 3 in Table 4 shows that we strongly reject the hypothesis that current and past use of cannabis have the same effect on opinions. Current cannabis use has a substantial bigger effect on opinions than past cannabis use. In an unreported estimation (see for details Palali and van Ours 2014), we also find that the frequency of current cannabis use matters. More frequent the cannabis use, i.e. more self-interest leads to a more favorable opinion about cannabis legalization. Casual users do not differ from past users. For individuals who rarely use cannabis, inside information is driving the results rather than self-interest, which is consistent with our interpretations of the results. This is particularly important because several studies, for example Caulkins and Pacula (2006) and Kilmer et al. (2014), find that even though they constitute a small group heavy users account for most of the cannabis transactions.

5.3 Robustness checks

5.3.1 Sensitivity to policy statements

Table 5 presents the results of a sensitivity analysis focusing on other statements on cannabis policy or drug policy in general. For reasons of comparison panel a replicates the main findings of Table 4. Panel b present the parameter estimates for the second policy statement on coffeeshops: It should be permitted to sell cannabis at coffeeshops. We obtain very similar results. Both current use of cannabis and past use of cannabis have positive and significant effects on opinions. In panel b of column 2, similar to column 2 of Table 4, the parameter estimate of current use is found to be twice as large as the coefficient estimate of past use.Footnote 11 This suggests that the magnitude of the effect of self-interest is almost the same as that of inside information. For opinions on the first and the second type of cannabis policy, there is a causal effect from past cannabis use to opinions. Individuals that used cannabis in the past changed their opinion after they had personal experience with cannabis toward a more liberal policy. They became more likely to support no-prohibition and more likely to support cannabis legalization. This suggests that cannabis use is not as harmful as they originally thought.

Panels c–f of Table 1 give descriptive information about opinions on other drug policy statements which are not directly related to availability of cannabis. For all these policies, the distribution of the responses is very skewed. Almost 90 % of the individuals agree with the statements that coffeeshops should not sell cannabis to people below 18 years old, the government should organize education campaigns against drugs, there should not be coffeeshops in the vicinity of schools and the government should ensure that schools organize education campaigns against drugs. The percentages of those who agree with a specific cannabis policy remain high irrespective of the user status. Nevertheless, to investigate whether there was a causal effect from cannabis use to opinions, we performed a similar type of analysis as for the two main policy statements that referred to cannabis prohibition and cannabis legalization. Since the following policy statements are not directly about availability of cannabis, they serve as falsification analysis on the self-interest aspect of cannabis use.

Panels c and d of Table 5 present the parameter estimates of the effects of current and past cannabis use on restrictions on sale of cannabis. Concerning no sale of cannabis to youngsters, there is correlation with user status, but this disappears once correlated unobserved heterogeneity is taken into account. Apparently, individuals who started using cannabis did not change their opinion on no sale of cannabis to youngsters. They had a different opinion all along. They were less likely to support the idea of no sale of cannabis to youngsters anyway. The findings for the statement that there should be no coffeeshops near schools is somewhat different. In order to explore the possible reason behind the significant negative parameter estimate, we performed the same correlated analysis by dividing the current cannabis use variable into 3 parts: those who frequently (more than once) used cannabis in the last 30 days, those who used cannabis only once in the last 30 days but started using cannabis at an earlier age and those who for the first time used cannabis only once in the last 30 days. Although not reported here, the results after this distinction show that the negative effect is located among those who used cannabis for the first time in the last 30 days, which has a very small number of observations. Once they are ignored, there is no effect. Moreover, since these people cannot accumulate inside information from one time use and they are mostly below 25 years old, we argue that self-interest plays a small role.Footnote 12

Panels e and f of Table 5 show the main parameter estimates for statements on education programs. For education campaigns, there is no big difference between the univariate model and the correlated model. This suggests that initially opinions were not different but once some individuals started using cannabis they changed their minds. Moreover, the fact that there is no difference between the effects of past use and current use suggests that it is inside information that is driving the results. Apparently, after personal experience with cannabis, some individuals were less inclined to support education campaigns because they thought there was less need for such campaigns. For drugs education at school, there is no difference in opinions according to user status.

All in all, the findings for the specific types of drug policy show that cannabis use did not have a big effect on opinions and if it did such as is the case for education campaigns, inside information is driving the results.Footnote 13 As expected self-interest does not play a significant role in shaping opinions about these policy statements.

5.3.2 Placebo tests

In order to investigate the robustness of our findings we performed a range of sensitivity checks of which we briefly report the results (see for details Palali and van Ours 2014). First, by way of placebo analysis we investigate the effect of past and current cannabis use on opinions about policies unrelated to cannabis use. The first placebo analysis is on the opinions about alcohol legislation. We use information about opinions on various types of alcohol policy all aiming at restricting access to alcohol. The proposed policies are: no sale of alcohol in supermarkets, banning alcohol advertisements, no sale of alcohol to youngsters under age 16, no happy hours in bars and discos, no sale of alcohol in places which are frequently visited by youngsters. Using the same correlated model approach, we find that opinions about these alcohol policies are not different for cannabis users and non-cannabis users. The second placebo analysis is on the opinions about government policies which are completely unrelated to risky health behaviors. We use information about opinions on whether study grants should be replaced by study loans and opinions on citizens’ influence on government policies. Again there is no effect on these opinions of current or past cannabis use.

5.3.3 Sensitivity to model specifications

In a further set of robustness checks, we investigate the sensitivity of our baseline results to various model specifications (see for details Palali and van Ours 2014). We remove education dummies from starting rate analysis cannabis use may affect educational attainment. We add political preference dummies in the starting rates. Again, our conclusions remain the same. One issue with retrospective responses about substance use is that there might be measurement errors due to recall bias. In order to investigate if our results are sensitive to such a recall bias, we restrict our sample to a much younger cohort as they are expected to recall more accurately. If we use information on individuals who were born after 1969 we lose almost half of our main sample but still obtain similar results. We also include several control variables regarding different aspects of cannabis use. Adding variables for opinions about the criminal aspect of cannabis use, peer use of cannabis and duration of cannabis use does not affect our main conclusions. Moreover, using ordered logit models instead of probit models yields the same results. As a final robustness analysis we estimate the univariate and correlated models by reducing opinions variables to a three-point scale. The parameter estimates are very similar as before. This indicates that our findings are mainly driven by differences between individuals who agree or disagree to given policy statements and not by differences between those who agree (disagree) or definitely agree (definitely disagree).

5.4 Magnitude of the effects

To indicate the magnitude of the effect of past and current use of cannabis, we simulated the probabilities for each alternative in the ordered response variable. The simulation results are given in Table 6. The first panel presents the results for the first policy statement (cannabis should be legalized). As shown there is a large effect of cannabis use. The estimated probability of agreeing with legalizing cannabis is 33 % for our reference person who has never used cannabis (row (3)). If that reference person used cannabis in the past, support for no-prohibition increases to 60 % and if this person is still using cannabis the support for no-prohibition jumps to 81 %. Similarly, the second panel presents the simulation results for the second policy statement. The estimated probability of agreeing with the idea of selling cannabis at coffeeshops is 36 % for a never user reference person. This probability increases to 53 % if this reference person is a past-user and to 74 % if the individual is a current user. Similarly the probability of disagreeing decreases from 43 to 26 and 11 %, respectively. A comparison of these figures with the unconditional distribution given in Table 1 shows that even though differences between cannabis users and non-users decrease after controlling for observable and unobservable factors, they remain considerable.

6 Conclusions

Previous studies show that cannabis users are more in favor of cannabis legalization than individuals who never used cannabis. Interesting as this may be in itself, it does not necessarily imply that opinions are influenced by cannabis use in a causal way. Individuals who are more likely to consume cannabis may also be more in favor of legalization without the personal experience affecting opinions. Knowing whether or not there is a causal effect from cannabis use is interesting because if so, it reveals how potential dangers of cannabis use are assessed. If cannabis use increases the support for legalizing cannabis, then this reveals that cannabis use may not be so harmful as individuals were inclined to think before they started using cannabis. However, such a causal effect may also have to do with self-interest, i.e. the expectation that cannabis legalization will induce easier access and perhaps lower prices.

We use data from a 2008 survey which includes detailed questions about cannabis use and opinions about cannabis policies in the Netherlands. From our analysis, we conclude that there is a causal effect of personal experience with cannabis use on the support given to more liberal cannabis policies. Those who currently use cannabis and those who used it in the past are more in favor of legalization. The opinion of current cannabis users may be driven by self-interest and inside information but the opinion of past users will be driven mainly by inside information about the dangers of cannabis use. From the significance of the effect of past cannabis use, we conclude that cannabis use may not be as harmful as cannabis users originally thought it was and non-users are inclined to think. Our analysis suggests that as the share of cannabis users in the population goes up support for cannabis legalization will increase.

Notes

What the optimal cannabis policy is from an economic point of view is not clear. Economic arguments are based on the tradeoff between legalizing cannabis which would allow taxes to be introduced on cannabis use or prohibiting cannabis use because it is easier to limit cannabis supply than to implement taxation. See for studies that analyze the pros and cons of legalization (Becker et al. 2006; Caulkins et al. 2012; Glaeser and Shleifer 2001; Miron and Zwiebel 1995).

The gateway hypothesis suggests cannabis use can be a gateway to hard drug use such as cocaine or heroin.

The influence of self-interest is present also in the use of other (legal) drugs. Using Californian data, Green and Gerken (1989) find that self-interest plays a decisive role in forming attitudes toward restrictions on smoking and cigarette taxes.

In the context of a MPH model describing the dynamics in cannabis, correlated models have been used for example by Van Ours and Williams (2012) and Van Ours and Williams (2011) to study the relationship between cannabis use and health and by Van Ours (2007) to study wage effects of cannabis use. Cannabis use is not the only context in which such methods are used. In labor economics literature, Abbring et al. (2005), Arni et al. (2013) and Van Ours (2004) for example, use similar methods. Other examples are Fevang et al. (2014) who analyze Norwegian absenteeism jointly modeling the flow from presence to absence and back and Richardson and van den Berg (2013) who study the effect of labor market training on the job finding rates of Swedish unemployed workers.

Note that the expectation about the effect of past use on opinions is not very clear. It can be also the case that past users face the negative effects of cannabis use and regret the fact that they have used cannabis. Our empirical findings suggests that there is no regret.

If no birth year restriction is imposed on the sample, these figures are 39 and 43 %, respectively. In 1998 this distribution was very much the same: Back then, 43 % of the Dutch population of 19 years and older thought that coffeeshops were admissible while 46 % thought they were not admissible (Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau 1998).

For simplicity we write \(x_{3}^{\prime }\beta _p = x_{2}^{\prime }\beta _p+ \rho _c c_c + \rho _p c_p\).

We assume that educational attainment represents ability since many individuals start using cannabis before finishing school.

The first likelihood ratio test statistic has a value of 6.6 which is significant with 1 degree of freedom (\(\epsilon _b\)).

In countries where cannabis use is illegal, past users can still be affected by self-interest because the reason they do not use cannabis today can be illegality itself. In other words, they might have quit using cannabis because of the opportunity cost of being arrested. In such as case, they can still have a self-interest in supporting liberal policies, as they think liberal policies would remove the possible future costs of using cannabis. However, this is not the case for the population in the Netherlands where cannabis market is regulated for both supply and demand. Also note that society as a whole is constantly learning about negative effects or absence of negative effects of cannabis use through the accumulation of scientific evidence and its public presentation. All individuals have potential access to public and private signals about the self-harm effects of cannabis use. Own use (current or past) is not the only way to learn about this margin, but the most effective indeed since it is first-hand information. Although all the other information is available to all individuals, first-hand information is only available to cannabis users.

Note that for the second policy, we can identify a significant unobserved heterogeneity in the univariate model although the estimated probability parameter is not well-identified. For this opinion, we can compare univariate models with unobserved heterogeneity and the correlated models through likelihood ratio tests. The results indicate that we fail to reject the correlated model against the univariate one. Therefore, there is further evidence supporting the findings of the previous LR tests that correlation between unobserved heterogeneity affecting opinions and cannabis use dynamics is significant.

Making the same distinction in two main legalization policies whose results are given in Table 4 did not make any changes. This distinction seems to make a difference only for this specific policy statement on the location of coffeeshops.

The exception to these findings is the negative of current cannabis use on support for the ban of coffeeshops near schools. It is hard to imagine that this has a causal interpretation.

References

Abbring JH, van den Berg GJ, van Ours JC (2005) The effect of unemployment insurance sanctions on the transition rate from unemployment to employment. Econ J 115:602–630

Arni P, Lalive R, van Ours JC (2013) How effective are unemployment benefit sanctions? Looking beyond unemployment exit. J Appl Econom 28:1153–1178

Arseneault L, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray R (2004) Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. Br J Psychiatry 184:110–117

Becker G, Murphy K, Grossman M (2006) The market for illegal goods: the case of drugs. J Polit Econ 114:38–60

Bieleman B, Beelen A, Nijkamp R, de Bie E (2007) Coffeeshops in Nederland. Aantallen en gemeentelijk beleid in 2007 (“Coffeeshops in the Netherlands. Numbers and local policy in 2007”). Intraval, Groningen

Brook J, Balka E, Whiteman M (1999) The risks for late adolescence of early adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health 89:1549–1554

Caulkins J, Pacula R (2006) Marijuana markets: inference from reports by the household population. J Drug Issues 36:173–200

Caulkins J, Coulson C, Farber C, Vesely J (2012) Marijuana legalization: certainty, impossibility, both, or neither? J Drug Policy Anal 5:1–27

De Graaf R, Radovanovic M, Van Laar M, Fairman B, Degenhardt L (2010) Early cannabis use and estimated risk of later onset of depression spells: epidemiologic evidence from the population-based World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Am J Epidemiol 172:149–159

Ellickson P, Collins R, Bell R (1999) Adolescent use of illicit drugs other than marijuana: how important is social bonding and for which ethnic groups? Subst Use Misuse 34:317–346

European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2013) Models for the legal supply of cannabis: recent developments. Lisbon

Fevang E, Markussen S, Roed K (2014) The sick pay trap. J Lab Econ 2:305–336

French MT, Roebuck MC, Alexandre PK (2001) Illicit drug use, employment & labour force participation. South Econ J 68(2):349–368

Glaeser E, Shleifer A (2001) A reason for quantity regulation. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 91:431–435

Green DP, Gerken AE (1989) Self-interest and public opinion toward smoking restrictions and cigarette taxes. Public Opin Q 53:1–16

Heckman JJ, Singer B (1984) A method for minimizing the impact of distributional assumptions in econometric models for duration data. Econometrica 52:271–320

Jansen A (1991) Cannabis in Amsterdam. A geography of hashish and marihuana. Countinho, Muiderberg

Kilmer B, Everingham S, Caulkins J, Midgette G, Reuters P, Burns R, Han B, Lundberg R (2014) What America’s users spend on illegal drugs: 2000–2010. Office of National Drug Control Policy

Miron J, Zwiebel J (1995) The economic case against drug prohibition. J Econ Perspect 9:175–192

Mroz TA (1999) Discrete factor approximations in simultaneous equation model: estimating the impact of a dummy endogenous variable on a continious outcome. J Econom 92:233–274

Orphanides A, Zervos D (1995) Rational addiction with learning and regret. J Political Econ 103:739–758

Palali A, van Ours JC (2014) Cannabis use and support for cannabis legalization. CEPR Discussion Paper 9944

Palali A, van Ours JC (2015) Distance to cannabis shops and age of onset of cannabis use. Health Econ 24(11):1483–1501

Richardson K, van den Berg GJ (2013) Duration dependence versus unobserved heterogeneity in treatment effects: Swedish labor market training and the transition rate to employment. J Appl Econom 28:325–351

Skretting A (1993) Attitude of the Norwegian population to drug policy and drug-offences. Addiction 88:125–131

Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau (1998) Sociale en Culturele Verkenningen 1998. VUGA Uitgeverij, Den Haag

Trevino RA, Richard AJ (2002) Attitudes towards drug legalization among drug users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 28(1):91–108

Van der Sar R, Brouwers E, van de Goor L, Garretsen H (2011) The opinion on Dutch cannabis policy measures: a cross-sectional survey. Drugs: education, prevention and policy 18(3):161–171

Van Ours JC (2004) A pint a day raises a man’s pay; but smoking blows that gain away. J Health Econ 23(5):863–886

Van Ours JC (2006) Cannabis, cocaine and jobs. J Appl Econom 21:897–917

Van Ours JC (2007) The effect of cannabis use on wages of prime age males. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 69:619–634

Van Ours JC, Williams J (2011) Cannabis use and mental health problems. J Appl Econom 26:1137–1156

Van Ours JC, Williams J (2012) The effects of cannabis use on physical and mental health. J Health Econ 31:564–577

Van Ours JC, Williams J (2015) Cannabis use and its effects on health, education and labor market success. J Econ Surv 29(5):993–1010

Van Ours JC, Williams J, Fergusson D, Horwood L (2013) Cannabis use and suicidal ideation. J Health Econ 32:524–537

Van Solinge T (1999) Dutch drug policy in a European context. J Drug Issues 29(3):511–528

Williams J, van Ours JC, Grossman M (2016) Attitudes to legalizing cannabis use. Health Econ 25:1201–1216

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to CentERdata for making their LISS data available for this paper. The authors also thank seminar participants in Canberra (ANU, Research School of Economics), Helsinki (University), Leuven (University), Sydney (University of Technology) and Tilburg (CentER) as well as two anonymous referees for helpful comments on a previous version of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Palali, A., van Ours, J.C. Cannabis use and support for cannabis legalization. Empir Econ 53, 1747–1770 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-016-1172-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-016-1172-7