Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The terminology for anorectal dysfunction in women has long been in need of a specific clinically-based Consensus Report.

Methods

This Report combines the input of members of the Standardization and Terminology Committees of two International Organizations, the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and the International Continence Society (ICS), assisted on Committee by experts in their fields to form a Joint IUGA/ICS Working Group on Female Anorectal Terminology. Appropriate core clinical categories and sub classifications were developed to give an alphanumeric coding to each definition. An extensive process of twenty rounds of internal and external review was developed to exhaustively examine each definition, with decision-making by collective opinion (consensus).

Results

A Terminology Report for anorectal dysfunction, encompassing over 130 separate definitions, has been developed. It is clinically based with the most common diagnoses defined. Clarity and user-friendliness have been key aims to make it interpretable by practitioners and trainees in all the different specialty groups involved in female pelvic floor dysfunction. Female-specific anorectal investigations and imaging (ultrasound, radiology and MRI) has been included whilst appropriate figures have been included to supplement and help clarify the text. Interval review (5–10 years) is anticipated to keep the document updated and as widely acceptable as possible.

Conclusions

A consensus-based Terminology Report for female anorectal dysfunction terminology has been produced aimed at being a significant aid to clinical practice and a stimulus for research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In regards to definition of various types of urinary incontinence, the interested reader can refer to (Haylen 2010) [7].

A history of receptive anal intercourse has been shown to increase the risk of anal incontinence [12].

Soiling is a bothersome disorder characterized by continuous or intermittent liquid anal discharge. It should be differentiated from discharge due to fistulae, proctitis, hemorrhoids, and prolapse. Patients complain about staining of underwear and often wear protection.

-

The discharge may cause inflammation of the perineal skin with excoriation, perianal discomfort, burning sensation, and itching,

It often indicates the presence of an impaired internal sphincter function or a solid fecal mass in the rectum but could also be due to the inability to maintain hygiene due to hemorrhoids.

-

Rome III criteria for functional constipation:

1. Must include two or more of the following:

a. Straining during at least 25 % of defecations.

b. Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25 % of defecations.

c. Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25 % of defecations.

d. Sensation of anorectal obstruction/ blockage for at least 25 % of defecations.

e. Manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25 % of defecations (e.g., digitalevacuation, support of the pelvic floor).

f. Fewer than three defecations per week.

2. Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives.

3. Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

* Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

Difficulty evacuating stool, requiring straining efforts at defecation often associated with lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, feeling of anorectal blockage/obstruction or manual assistance to defecate (or inability to relax EAS/dyssynergic defecation).

Anorectal prolapse can be due to hemorrhoidal, mucosal, rectal prolapse, or rectal intussusception. These definitions are further explained under “Signs.”

This refers to pain localized to the anorectal region, and may include pain, pressure, or discomfort in the region of the rectum, sacrum, and coccyx that may be associated with pain in the gluteal region and thighs.

Fissure pain during, and particularly after, defecation is commonly described as passing razor blades or glass shards See FN10.

Receptive anal intercourse is associated with increased risk of both any female sexual dysfunction [14], as well as with specifically female sexual arousal disorder with distress [15] (“a persistent or recurrent inability to attain [or to maintain until completion of the sexual activity] an adequate wetness and vaginal swelling response of sexual excitement”). The association of receptive anal intercourse with sexual dysfunction might be due to physiological and/or psychological processes. The psychological factors including emotional development problems [16], poorer mood [17], poorer intimate attachment [18] as well as general dissatisfaction are associated with women’s receptive anal intercourse [19]. Physiologic factors could include that: (1) mechanical stimulation of the anus and rectum during anal intercourse increases hemorrhoid risk; (2) women with hemorrhoidectomy have impaired sexual function; and (3) persons with hemorrhoids who have not yet had hemorrhoidectomy “are more likely to have abnormal perineal descent with pudendal neuropathy.” [20, 21] Thus, pudendal nerve dysfunction could be one mechanism leading to sexual dysfunction, and this might be the case even in the absence of diagnosed haemorrhoids [13].

A history of receptive anal intercourse has been shown to increase the risk of anal incontinence, rectal bleeding, and anal fissure [12].

Unlike dyspareunia (from coitus), it might be normal to experience pain or discomfort during receptive anal intercourse.

This may be accompanied by a finding of decreased anal resting tone (in some cases, the result of anal intercourse)—see under Signs. Damage to the internal anal sphincter is the likely basis for the laxity. Unlike stool passage, receptive anal intercourse is not likely to elicit reflex relaxation of the internal sphincter.

Pruritus ani has been classified into primary and secondary. The primary form is the classic syndrome of idiopathic pruritus ani. The secondary form implies an identifiable cause or a specific diagnosis.

With perianal hematomas, the lump may be anywhere around the anal margin and may be multiple. Pilonidal sinuses are usually a small mid-line pit with epithelialized edges.

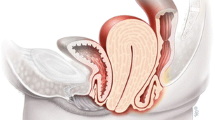

A transverse defect rectocele occurs simply by a detachment of the perineal body from the rectovaginal fascia. The hammock of rectovaginal fascia supporting the rectum remains intact but separates from the perineal body. A midline vertical defect is created by a midline separation of the rectovaginal fascia, and a separation of the rectovaginal fascia can occur from it’s lateral attachments. Rectoceles are more commonly situated in the mid to distal aspect of the posterior vaginal wall.

Symptoms of levator ani syndrome are painful rectal spasm, typically unrelated to defecation, usually lasting >20 min. The pain may be brief and intense or a vague ache high in the rectum. It may occur spontaneously or with sitting and can waken the patient from sleep and occurs more often on the left. The pain may feel as if it would be relieved by the passage of gas or a bowel movement. In severe cases, the pain can persist for many hours and recur frequently. During clinical evaluation: a dull ache to the left 5 cm above the anus or higher in the rectum and a feeling of constant rectal pressure or burning. Physical examination can exclude other painful rectal conditions (e.g., thrombosed hemorrhoids, fissures, abscesses, scarring from previous surgery). Physical examination is often normal, although tenderness or tightness of the levator muscle, usually on the left, may be present. Occasionally the cause can be low back disorders. Coccydynia (coccygodynia) is complaint of pain and point tenderness of the coccyx (this is NOT anorectal pain).

Proctalgia fugax most often occurs in the middle of the night and lasts for seconds to 20 min. During an episode, which sometimes occurs after orgasm, the patient feels spasm-like, sometimes excruciating pain in the anus, often misinterpreted as a need to defecate. Because of the high incidence of internal anal sphincter thickening with the disorder, it is thought to be a disorder of the internal sphincter or that it is a neuralgia of pudendal nerves. It tends to occur infrequently (once a month or less). Like all ordinary muscle cramps, it is a severe, deep rooted pain. Defecation can worsen the spasm, but may relieve it [112], or provide a measure of comfort. The pain might subside by itself as the spasm disappears on its own, or may persist or recur during the same night. Patients with proctalgia fugax are usually asymptomatic during the anorectal examination, leaving no signs or findings to support the condition, which is based on symptoms by history taking, diagnostic criteria, described above, and the exclusion of underlying organic disease (anorectal or endopelvic) with proctalgia [113].

The condition is also known as pudendal neuropathy, pudendal nerve entrapment, cyclist’s syndrome, pudendal canal syndrome, or Alcock’s syndrome. The Nantes criteria [13] includes:

-

1.

Pain in the anatomical region of pudendal nerve innervation.

-

2.

Pain that is worse with sitting.

-

3.

No waking at night with pain.

-

4.

No sensory deficit on examination.

-

5.

Relief of symptoms with a pudendal block.

Primary symptoms of PN include:

-

a)

Pelvic pain with sitting that may be less intense in the morning and increase throughout the day. Symptoms may decrease when standing or lying down. The pain can be perineal, rectal or in the clitoral/penile area; it can be unilateral or bilateral.

-

b)

Sexual dysfunction. In women, dysfunction manifests as pain or decreased sensation in the genitals, perineum or rectum. Pain may occur with or without touch. It may be difficult or impossible for the woman to achieve orgasm.

-

c)

Difficulty with urination/defecation. Patients may experience urinary hesitancy, urgency and/or frequency. Post-void discomfort is not uncommon. Patients may feel that they have to “strain” to have a bowel movement and the movement may be painful and/or result in pelvic pain after. Constipation is also common among patients with PN. In severe cases, complete or partial urinary and/or fecal incontinence may result.

-

d)

Sensation of a foreign object being within the body. Some patients will feel as though there is a foreign object sitting inside the vagina or the rectum.

It is important to note PN is largely a “rule out” condition. In other words, because its symptoms can be indicative of another problem, extensive testing by physical examination, assessment by touch, pinprick, bimanual pelvic palpation with attention to the pelvic floor muscles, in particular the levator and obturator muscles, tenderness of the bladder and sacrospinous ligaments are required to ensure that symptoms are not related to another condition. Maximum tenderness, or a trigger point can be produced by applying pressure to the ischial spine. Palpation of this area can reproduce pain and symptoms as a positive Tinel’s sign [114].

As PN is a diagnosis of exclusion, other conditions that should be excluded include coccygodynia, piriformis syndrome, interstitial cystitis, vulvodynia, vestibulitis, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, proctalgia, anorectal neuralgia, pelvic contracture syndrome/pelvic congestion, proctalgia fugax, or levator ani syndrome.

In addition to eliminating other diagnoses, it is important to determine if the PN is caused by a true entrapment or other compression/tension dysfunctions. In almost all cases, pelvic floor dysfunction accompanies PN. Electrodiagnostic studies will help the practitioner determine if the symptoms are caused by a true nerve entrapment or by muscular problems and neural irritation.

-

1.

References

Snooks SJ, Setchell M, Swash M, et al. Injury to innervation of pelvic floor sphincter musculature in childbirth. Lancet. 1984;2:546–50.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1905–11.

Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, et al. Occult anal sphincter injuries—Myth or reality? BJOG. 2006;113:195–200.

Dal Corso HM, D’Elia A, De Nardi P, et al. Anal endosonography: a survey of equipment, technique and diagnostic criteria adopted in nine Italian centers. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11:26–33.

Kapoor DS, Sultan AH, Thakar R, et al. Management of complex pelvic floor disorders in a multidisciplinary pelvic floor clinic. Color Dis. 2008;10:118–23.

Milsom I, Altman D, Lapitan MC, et al. Epidemiology of urinary (UI) and faecal (FI) incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. 4th international consultation on incontinence. Paris: Health Publication Ltd; 2009. p. 35–111. Chapter 1.

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:5–26.

Rosier PF, de Ridder D, Meijlink J, et al. Developing evidence-based standards for diagnosis and management of lower urinary tract or pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:621–4.

Stedman’s medical dictionary. 28th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott and Wilkins; 2006. p. 1884.

Abrams P, Blaivas JG, Stanton SL, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. The international continence society committee on standardisation of terminology. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1988;114:5–19.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the international continence society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78.

Miles AJ, Allen-Mersh TG, Wastell C. Effect of anoreceptive intercourse on anorectal function. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:144–7.

Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:306–10.

Brody S, Weiss P. Heterosexual anal intercourse: increasing prevalence, and association with sexual dysfunction, bisexual behavior, and venereal disease history. J Sex Marital Ther. 2011;37:298–306.

Weiss P, Brody S. Female sexual arousal disorder with and without a distress criterion: prevalence and correlates in a representative Czech sample. J Sex Med. 2009;6:3385–94.

Costa RM, Brody S. Immature defense mechanisms are associated with lesser vaginal orgasm consistency and greater alcohol consumption before sex. J Sex Med. 2010;7:775–86.

Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD, Orr DP. Factors associated with event level anal sex and condom use during anal sex among adolescent women. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:232–7.

Costa RM, Brody S. Anxious and avoidant attachment, vibrator use, anal sex, and impaired vaginal orgasm. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2493–500.

Brody S, Costa RM. Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile-vaginal intercourse, but inversely with other sexual behavior frequencies. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1947–54.

Bruck CE, Lubowski DZ, King DW. Do patients with haemorrhoids have pelvic floor denervation? Int J Color Dis. 1988;3:210–4.

Lin YH, Stocker J, Liu KW, et al. The impact of hemorrhoidectomy on sexual function in women: a preliminary study. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:343–7.

Toozs-Hobson P, Freeman R, Barber M, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:527–35.

Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the international continence society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:374–80.

Laycock J. Clinical evaluation of pelvic floor. In: Schussler B, Laycock J, Norton P, Stanton S, editors. Pelvic floor re-education. London: Springer; 1994. p. 42–8.

Bo K, Finckenhagen HB. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:883–7.

Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bourbonnais D, et al. Pelvic floor maximal strength using vaginal digital assessment compared to dynamometric measurements. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:336–41.

Isherwood PJ, Rane A. Comparative assessment of pelvic floor strength using a perineometer and digital examination. BJOG. 2000;107:1007–11.

Jeyaseelan S, Haslam J, Winstanley J, et al. Digital vaginal assessment: an inter-tester reliability study. Physiotherapy. 2001;87:243–50.

Mumenthaler M, Appenzeller O. Neurologic differential diagnosis. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 1992. p. 122.

Montenegro ML, Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Rosa e Silva JC, et al. Importance of pelvic muscle tenderness evaluation in women with chronic pelvic pain. Pain Med. 2010;11:224–8.

Kotarinos RK. CP/CPPS pelvic floor dysfunction, evaluation and treatment. In: Potts Jeannette M, editor. Genitourinary pain and inflammation: diagnosis and management. Totowa: Humana Press; 2008. p. 303–14. Chapter 20.

Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, et al. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population: a prospective study. Gut. 1992;33:818–24.

Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4.

Manning AP, Wyman JB, Heaton KW. How trustworthy are bowel histories? Comparison of recalled and recorded information. Br Med J. 1976;2:213–4.

Bharucha AE, Seide BM, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Insights into normal and disordered bowel habits from bowel diaries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:692–8.

Ashraf W, Park F, Lof J, et al. An examination of the reliability of reported stool frequency in the diagnosis of idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:26–32.

Kelleher C, Staskin D, Cherian P, et al. Patient-reported outcome assessment. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. ICUD-EAU 5th international consultation on incontinence. Paris: ICUD-EAU; 2013. p. 389–427. Chapter 5B.

Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77–97.

Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, et al. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80.

Maeda Y, Pares D, Norton C, et al. Does the St. Mark’s incontinence score reflect patients’ perceptions? A review of 390 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:436–42.

Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Fecal incontinence quality of life scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:9–16.

Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1525–32.

Cotterill N, Norton C, Avery KN, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a new patient-completed questionnaire for evaluating anal incontinence symptoms and impact on quality of life: the ICIQ-B. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1235–50.

Cotterill N, Norton C, Avery KN, et al. A patient-centered approach to developing a comprehensive symptom and quality of life assessment of anal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:82–7.

Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of the patient assessment of constipation quality of life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:540–51.

Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, et al. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:870–7.

Frank L, Flynn J, Rothman M. Use of a self-report constipation questionnaire with older adults in long-term care. Gerontology. 2001;41:778–86.

Slappendel R, Simpson K, Dubois D, et al. Validation of the PAC-SYM questionnaire for opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:209–17.

Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, et al. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681–5.

Altomare DF, Spazzafumo L, Rinaldi M, et al. Set-up and statistical validation of a new scoring system for obstructed defaecation syndrome. Color Dis. 2008;10:84–8.

Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, et al. AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:735–60.

Rao SS, Azpiroz F, Diamant N, et al. Minimum standards of anorectal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:553–9.

Gundling F, Seidl H, Scalercio N, et al. Influence of gender and age on anorectal function: normal values from anorectal manometry in a large Caucasian population. Digestion. 2010;81:207–13.

Rao SS, Hatfield R, Soffer E, et al. Manometric tests of anorectal function in healthy adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:773–83.

Read NW, Harford WV, Schmulen AC, et al. A clinical study of patients with fecal incontinence and diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:747–56.

Caruana BJ, Wald A, Hinds JP, et al. Anorectal sensory and motor function in neurogenic fecal incontinence. Comparison between multiple sclerosis and diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:465–70.

Orkin BA, Hanson RB, Kelly KA, et al. Human anal motility while fasting, after feeding, and during sleep. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1016–23.

McHugh SM, Diamant NE. Effect of age, gender, and parity on anal canal pressures. Contribution of impaired anal sphincter function to fecal incontinence. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:726–36.

Rao SS, Singh S. Clinical utility of colonic and anorectal manometry in chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:597–609.

Schizas AM, Emmanuel AV, Williams AB. Vector volume manometry—Methods and normal values. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:886–e393.

Schizas AM, Emmanuel AV, Williams AB. Anal canal vector volume manometry. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:759–68.

Jones MP, Post J, Crowell MD. High-resolution manometry in the evaluation of anorectal disorders: a simultaneous comparison with water-perfused manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:850–5.

Kumar D, Waldron D, Williams NS, et al. Prolonged anorectal manometry and external anal sphincter electromyography in ambulant human subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:641–8.

Ferrara A, Pemberton JH, Grotz RL, et al. Prolonged ambulatory recording of anorectal motility in patients with slow-transit constipation. Am J Surg. 1994;167:73–9.

Ferrara A, Pemberton JH, Levin KE, et al. Relationship between anal canal tone and rectal motor activity. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:337–42.

Chiarioni G, Scattolini C, Bonfante F, et al. Liquid stool incontinence with severe urgency: anorectal function and effective biofeedback treatment. Gut. 1993;34:1576–80.

Wald A, Tunuguntla AK. Anorectal sensorimotor dysfunction in fecal incontinence and diabetes mellitus. Modification with biofeedback therapy. N Eng J Med. 1984;310:1282–7.

Merkel IS, Locher J, Burgio K, et al. Physiologic and psychologic characteristics of an elderly population with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1854–9.

Kamm MA, Lennard-Jones JE. Rectal mucosal electrosensory testing—Evidence for a rectal sensory neuropathy in idiopathic constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:419–23.

Andersen IS, Michelsen HB, Krogh K, et al. Impedance planimetric description of normal rectoanal motility in humans. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1840–8.

Wiesner A, Jost WH. EMG of the external anal sphincter: needle is superior to surface electrode. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:116–7.

Kiff ES, Swash M. Slowed conduction in the pudendal nerves in idiopathic (neurogenic) faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 1984;71:614–6.

Bliss DZ, Mellgren A, Whitehead WE, et al. Assessment and conservative management of faecal incontinence and quality of life in adults. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. ICUD-EAU 5th international consultation on incontinence. Paris: ICUD-EAU; 2013. p. 1443–86. Chapter 16.

Stoker J, Bartram CI, Halligan S. Imaging of the posterior pelvic floor. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:779–88.

Tubaro A, Vodušek DB, Amarenco G, et al. Imaging, neurophysiological testing and other tests. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. ICUD-EAU 5th international consultation on incontinence. Paris: ICUD-EAU; 2013. p. 507–622. Chapter 7.

Santoro GA, Wieczorek AP, Dietz HP, et al. State of the art: an integrated approach to pelvic floor ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:381–96.

Frudinger A, Halligan S, Bartram CI, et al. Female anal sphincter: age-related differences in asymptomatic volunteers with high-frequency endoanal US. Radiology. 2002;224:417–23.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Talbot IC, et al. Anal endosonography for identifying external sphincter defects confirmed histologically. Br J Surg. 1994;81:463–5.

Williams AB, Bartram CI, Halligan S, et al. Anal sphincter damage after vaginal delivery using three-dimensional endosonography. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:770–5.

Williams AB, Cheetham MJ, Bartram CI, et al. Gender differences in the longitudinal pressure profile of the anal canal related to anatomical structure as demonstrated on three-dimensional anal endosonography. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1674–9.

Santoro GA, Fortling B. The advantages of volume rendering in three-dimensional endosonography of the anorectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:359–68.

Dietz HP. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part I: two-dimensional aspects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:80–92.

Braekken IH, Majida M, Ellstrom-Engh M, et al. Test-retest and intra-observer repeatability of two-, three- and four-dimensional perineal ultrasound of pelvic floor muscle anatomy and function. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:227–35.

Dietz HP. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part II: three-dimensional or volume imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:615–25.

Santoro GA, Wieczorek AP, Stankiewicz A, et al. High-resolution threedimensional endovaginal ultrasonography in the assessment of pelvic floor anatomy: a preliminary study. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20:1213–22.

Santoro GA, Wieczorek AP, Shobeiri SA, et al. Interobserver and interdisciplinary reproducibility of 3D endovaginal ultrasound assessment of pelvic floor anatomy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2011;22:53–9.

Wagenlehner FME, Del Amo E, Santoro GA, et al. Live anatomy of the perineal body in patients with 3rd degree rectocele. Color Dis. 2013;15:1416–22.

Dobben AC, Terra MP, Deutekom M, et al. Anal inspection and digital rectal examination compared to anorectal physiology tests and endoanal ultrasonography in evaluating fecal incontinence. Int J Color Dis. 2007;22:783–90.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, et al. Prospective study of the extent of internal anal sphincter division during lateral sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1031–3.

Richter HE, Fielding JR, Bradley CS, et al. Endoanal ultrasound findings and fecal incontinence symptoms in women with and without recognized anal sphincter tears. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1394–401.

Starck M, Bohe M, Fortling B, et al. Endosonography of the anal sphincter in women of different ages and parity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:169–76.

Norderval S, Markskog A, Rossaak K, et al. Correlation between anal sphincter defects and anal incontinence following obstetric sphincter tears: assessment using scoring systems for sonographic classification of defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:78–84.

Dietz HP, Moegni F, Shek KL. Diagnosis of levator avulsion injury: a comparison of three methods. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:693–8.

Dietz HP, Steensma AB. Posterior compartment prolapse on two-dimensional and three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hypermobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:73–7.

Stoker J. Anorectal and pelvic floor anatomy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:463–75.

Tan E, Anstee A, Koh DM, et al. Diagnostic precision of endoanal MRI in the detection of anal sphincter pathology: a meta-analysis. Int J Color Dis. 2008;23:641–51.

Mortele KJ, Fairhurst J. Dynamic MR defecography of the posterior compartment: indications, techniques and MRI features. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:462–72.

Lakeman MM, Zijta FM, Peringa J, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging to quantify pelvic organ prolapse: reliability of assessment and correlation with clinical findings and pelvic floor symptoms. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1547–54.

Bolog N, Weishaupt D. Dynamic MR imaging of outlet obstruction. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:293–302.

Dobben AC, Terra MP, Slors JF, et al. External anal sphincter defects in patients with fecal incontinence: comparison of endoanal MR imaging and endoanal US. Radiology. 2007;242:463–71.

Terra MP, Beets-Tan RG, van Der Hulst VP, et al. Anal sphincter defects in patients with fecal incontinence: endoanal versus external phased-array MR imaging. Radiology. 2005;236:886–95.

DeLancey JO, Sorensen HC, Lewicky-Gaupp C, et al. Comparison of the puborectal muscle on MRI in women with POP and levator ani defects with those with normal support and no defect. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:73–7.

Broekhuis SR, Fütterer JJ, Hendriks JC, et al. Symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction are poorly correlated with findings on clinical examination and dynamic MR imaging of the pelvic floor. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1169–74.

Brennan D, Williams G, Kruskal J. Practical performance of defecography for the evaluation of constipation and incontinence. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2008;29:420–6.

Maglinte DD, Hale DS, Sandrasegaran K. Comparison between dynamic cystocolpoproctography and dynamic pelvic floor MRI: pros and cons: which is the “functional” examination for anorectal and pelvic floor dysfunction? Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:952–73.

Groenendijk AG, Birnie E, de Blok S, et al. Clinical-decision taking in primary pelvic organ prolapse; the effects of diagnostic tests on treatment selection in comparison with a consensus meeting. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:711–9.

Rollandi GA, Biscaldi E, DeCicco E. Double contrast barium enema: technique, indications, results and limitations of a conventional imaging methodology in the MDCT virtual endoscopy era. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:382–7.

Ghoshal UC, Sengar V, Srivastava D. Colonic transit study technique and interpretation: can these be uniform globally in different populations with non-uniform colon transit time? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:227–8.

Chan CLH, Lunniss PJ, Wang D, et al. Rectal sensorimotor dysfunction in patients with urge faecal incontinence: evidence from prolonged manometric studies. Gut. 2005;54:1263–72.

Santoro GA, Eitan BZ, Pryde A, et al. Open study of low-dose amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with idiopathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1676–81. discussion 1681–2.

Whitehead WE, Wald A, Diamant NE, et al. Functional disorders of the anus and rectum. Gut. 1999;45:II55–9.

Hibner M, Desai N, Robertson LJ, et al. Pudendal neuralgia. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:148–53.

Potter MA, Bartolo DC. Proctalgia fugax. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1289–90.

Robert R, Prat-Pradal D, Labat JJ, et al. Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: role of the pudendal nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 1998;20:93–8.

Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner D. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. London: Springer; 2007.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Obstetric perineal tears: an audit of training. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;15:19–23.

Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Structured hands-on training in repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): an audit of clinical practice. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:193–9.

Sultan AH. Editorial: obstetric perineal injury and anal incontinence. Clin Risk. 1999;5:193–6.

Norton C, Christiansen J, Butler U, et al. Anal incontinence. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. 2nd ed. Plymouth: Health Publication Ltd; 2002. p. 985–1044.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The management of third and fourth degree perineal tears. London: RCOG Press; 2015.

Fernando R, Sultan A, Kettle C, et al. Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD002866.

Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, et al. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:318–23.

Mahony R, Behan M, Daly L, et al. Internal anal sphincter defect influences continence outcome following obstetric anal sphincter injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:217. e1–5.

Chatoor D, Soligo M, Emmanuel A. Organising a clinical service for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:611–20.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge contributions from Dr Helen Frawley, Beth Shelley following ICS (V29 Jan 2015) IUGA website presentation of Version 30 (Aug15, Dr Alexis Schizas and Kari Bo at ICS Montreal (V33 8Oct15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Sultan has patent on anal sphincter blocks with royalties paid to the Mayday Childbirth Charity fund. He described the Sultan Classification of third degree tears and runs hands-on workshops on Perineal and Anal Sphincter Trauma (www.perineum.net.; A Monga: reports being Consultant for Gynecare and AMS and Speaker for Astellas and Pfizer and advisor for Allergan.; Dr. Lee reports personal fees from AMS, personal fees from BSCI, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Emmanuel served on advisory boards for Coloplast, Shire, Pfizer. Honoraria for talks from these companies as well as Ferring and Astra-Zeneca; Dr. Norton reported Consultancy for SCA, Coloplast, Shire, Dr Falk, Clinimed; Dr. Santoro has nothing to disclose; Dr. Hull has nothing to disclose; Dr. Berghmans has nothing to disclose; Dr. Brody has nothing to disclose; Dr. Haylen has nothing to disclose.

Additional information

This document is being published simultaneously in Neurourology and Urodynamics (NAU) and the International Urogynecology Journal (IUJ), the respective journals of the sponsoring organizations, the International Continence Society (ICS) and the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA).

Standardization and Terminology Committees IUGA* & ICS# - Joseph Lee*, Bernard T. Haylen*, Ash Monga#, Bary Berghmans#

Joint IUGA/ICS Working Group on Female Anorectal Terminology - Abdul H. Sultan, Ash Monga, Joseph Lee, Anton Emmanuel, Christine Norton, Giulio Santoro, Tracy Hull, Bary Berghmans, Stuart Brody, Bernard T. Haylen

Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI 10.1002/nau.23055.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sultan, A.H., Monga, A., Lee, J. et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female anorectal dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 28, 5–31 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3140-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3140-3