Abstract

Summary

The 1p36 region of the human genome has been identified as containing a QTL for BMD in multiple studies. We analysed the TNFRSF1B gene from this region, which encodes the TNF receptor 2, in two large population-based cohorts. Our results suggest that variation in TNFRSF1B is associated with BMD.

Introduction

The TNFRSF1B gene, encoding the TNF receptor 2, is a strong positional and functional candidate gene for impaired bone structure through the role that TNF has in bone cells. The aims of this study were to evaluate the role of variations in the TNFRSF1B gene on bone structure and osteoporotic fracture risk in postmenopausal women.

Methods

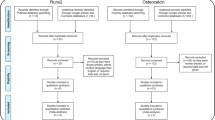

Six SNPs in TNFRSF1B were analysed in a cohort of 1,190 postmenopausal Australian women, three of which were also genotyped in an independent cohort of 811 UK postmenopausal women. Differences in phenotypic means for genotype groups were examined using one-way ANOVA and ANCOVA.

Results

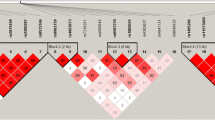

Significant associations were seen for IVS1+5580A>G with BMD and QUS parameters in the Australian population (P = 0.008 − 0.034) and with hip BMD parameters in the UK population (P = 0.005 − 0.029). Significant associations were also observed between IVS1+6528G>A and hip BMD parameters in the UK cohort (P = 0.0002 − 0.003). We then combined the data from the two cohorts and observed significant associations between both IVS1+5580A>G and IVS1+6528G>A and hip BMD parameters (P = 0.002 − 0.033).

Conclusions

Genetic variation in TNFRSF1B plays a role in the determination of bone structure in Caucasian postmenopausal women, possibly through effects on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Christiansen C et al (1994) The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 9:1137–1141

Prince RL, Dick I (1997) Oestrogen effects on calcium membrane transport: a new view of the inter-relationship between oestrogen deficiency and age-related osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 7 Suppl 3:S150–S154

Flicker L, Hopper JL, Rodgers L et al (1995) Bone density determinants in elderly women: a twin study. J Bone Miner Res 10:1607–1613

Krall EA, Dawson-Hughes B (1993) Heritable and life-style determinants of bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res 8:1–9

Michaelsson K, Melhus H, Ferm H et al (2005) Genetic liability to fractures in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 165:1825–1830

Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Hopper JL et al (1987) Genetic determinants of bone mass in adults. A twin study. J Clin Invest 80:706–710

Gueguen R, Jouanny P, Guillemin F et al (1995) Segregation analysis and variance components analysis of bone mineral density in healthy families. J Bone Miner Res 10:2017–2022

Dick IM, Devine A, Li S et al (2003) The T869C TGF beta polymorphism is associated with fracture, bone mineral density, and calcaneal quantitative ultrasound in elderly women. Bone 33:335–341

Dick IM, Devine A, Marangou A et al (2002) Apolipoprotein E4 is associated with reduced calcaneal quantitative ultrasound measurements and bone mineral density in elderly women. Bone 31:497–502

MacDonald HM, McGuigan FA, New SA et al (2001) COL1A1 Sp1 polymorphism predicts perimenopausal and early postmenopausal spinal bone loss. J Bone Miner Res 16:1634–1641

Mann V, Hobson EE, Li B et al (2001) A COL1A1 Sp1 binding site polymorphism predisposes to osteoporotic fracture by affecting bone density and quality. J Clin Invest 107:899–907

Devoto M, Shimoya K, Caminis J et al (1998) First-stage autosomal genome screen in extended pedigrees suggests genes predisposing to low bone mineral density on chromosomes 1p, 2p and 4q. Eur J Hum Genet 6:151–157

Devoto M, Specchia C, Li HH et al (2001) Variance component linkage analysis indicates a QTL for femoral neck bone mineral density on chromosome 1p36. Hum Mol Genet 10:2447–2452

Wilson SG, Reed PW, Bansal A et al (2003) Comparison of genome screens for two independent cohorts provides replication of suggestive linkage of bone mineral density to 3p21 and 1p36. Am J Hum Genet 72:144–155

Wynne F, Drummond FJ, Daly M et al (2003) Suggestive linkage of 2p22-25 and 11q12-13 with low bone mineral density at the lumbar spine in the Irish population. Calcif Tissue Int 72:651–658

Devoto M, Spotila LD, Stabley DL et al (2005) Univariate and bivariate variance component linkage analysis of a whole-genome scan for loci contributing to bone mineral density. Eur J Hum Genet 13:781–788

Karasik D, Cupples LA, Hannan MT et al (2004) Genome screen for a combined bone phenotype using principal component analysis: the Framingham study. Bone 34:547–556

Kimble RB, Bain S, Pacifici R (1997) The functional block of TNF but not of IL-6 prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice. J Bone Miner Res 12:935–941

Kimble RB, Srivastava S, Ross FP et al (1996) Estrogen deficiency increases the ability of stromal cells to support murine osteoclastogenesis via an interleukin-1and tumor necrosis factor-mediated stimulation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production. J Biol Chem 271:28890–28897

Roggia C, Gao Y, Cenci S et al (2001) Up-regulation of TNF-producing T cells in the bone marrow: a key mechanism by which estrogen deficiency induces bone loss in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:13960–13965

Bollerslev J, Wilson SG, Dick IM et al (2004) Calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphism A986S does not predict serum calcium level, bone mineral density, calcaneal ultrasound indices, or fracture rate in a large cohort of elderly women. Calcif Tissue Int 74:12–17

Prince RL, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS et al (2006) Effects of calcium supplementation on clinical fracture and bone structure: results of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly women. Arch Intern Med 166:869–875

Arden NK, Griffiths GO, Hart DJ et al (1996) The association between osteoarthritis and osteoporotic fracture: the Chingford Study. Br J Rheumatol 35:1299–1304

Hart DJ, Spector TD (1993) The relationship of obesity, fat distribution and osteoarthritis in women in the general population: the Chingford Study. J Rheumatol 20:331–335

Ireland P, Jolley D, Giles G et al (1994) Development of the Melbourne FFQ: a food frequency questionnaire for use in an Australian prospective study involving an ethnically diverse cohort. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 3:19–31

Hart DJ, Cronin C, Daniels M et al (2002) The relationship of bone density and fracture to incident and progressive radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee: the Chingford Study. Arthritis Rheum 46:92–99

Mullin BH, Wilson SG, Islam FM et al (2005) Klotho gene polymorphisms are associated with osteocalcin levels but not bone density of aged postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 77:145–151

Carter KW, McCaskie PA, Palmer LJ (2006) JLIN: a java based linkage disequilibrium plotter. BMC Bioinformatics 7:60

Dudbridge F (2003) Pedigree disequilibrium tests for multilocus haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol 25:115–121

Bollerslev J, Wilson SG, Dick IM et al (2005) LRP5 gene polymorphisms predict bone mass and incident fractures in elderly Australian women. Bone 36:599–606

Bustamante M, Nogues X, Enjuanes A et al (2007) COL1A1, ESR1, VDR and TGFB1 polymorphisms and haplotypes in relation to BMD in Spanish postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 18:235–243

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312:1254–1259

Diez-Perez A, Gonzalez-Macias J, Marin F et al (2007) Prediction of absolute risk of non-spinal fractures using clinical risk factors and heel quantitative ultrasound. Osteoporos Int 18:629–639

Albagha OM, Tasker PN, McGuigan FE et al (2002) Linkage disequilibrium between polymorphisms in the human TNFRSF1B gene and their association with bone mass in perimenopausal women. Hum Mol Genet 11:2289–2295

Tasker PN, Albagha OM, Masson CB et al (2004) Association between TNFRSF1B polymorphisms and bone mineral density, bone loss and fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:903–908

Spotila LD, Rodriguez H, Koch M et al (2003) Association analysis of bone mineral density and single nucleotide polymorphisms in two candidate genes on chromosome 1p36. Calcif Tissue Int 73:140–146

Xiao P, Liu PY, Lu Y et al (2005) Association tests of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and type II tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR2) genes with bone mineral density in Caucasians using a re-sampling approach. Hum Genet 117:340–348

Kuhnert P, Kemper O, Wallach D (1994) Cloning, sequencing and partial functional characterization of the 5′ region of the human p75 tumor necrosis factor receptor-encoding gene (TNF-R). Gene 150:381–386

Spotila LD, Rodriguez H, Koch M et al (2000) Association of a polymorphism in the TNFR2 gene with low bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res 15:1376–1383

Xu H, Zhao LJ, Lei SF et al (2005) The (CA)n polymorphism of the TNFR2 gene is associated with peak bone density in Chinese nuclear families. J Hum Genet 50:301–304

Xiong DH, Shen H, Zhao LJ et al (2006) Robust and comprehensive analysis of 20 osteoporosis candidate genes by very high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism screen among 405 white nuclear families identified significant association and gene-gene interaction. J Bone Miner Res 21:1678–1695

Santee SM, Owen-Schaub LB (1996) Human tumor necrosis factor receptor p75/80 (CD120b) gene structure and promoter characterization. J Biol Chem 271:21151–21159

Abu-Amer Y, Erdmann J, Alexopoulou L et al (2000) Tumor necrosis factor receptors types 1 and 2 differentially regulate osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem 275:27307–27310

Gilbert LC, Rubin J, Nanes MS (2005) The p55 TNF receptor mediates TNF inhibition of osteoblast differentiation independently of apoptosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288:E1011–1018

Bjornberg F, Lantz M, Olsson I et al (1994) Mechanisms involved in the processing of the p55 and the p75 tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors to soluble receptor forms. Lymphokine Cytokine Res 13:203–211

Tartaglia LA, Pennica D, Goeddel DV (1993) Ligand passing: the 75-kDa tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor recruits TNF for signaling by the 55-kDa TNF receptor. J Biol Chem 268:18542–18548

Acknowledgements and funding

The Australian study was supported by research grants from the Health-way Health Promotion Foundation of Western Australia, the Australian Menopause Society, the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Research Fund, and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, grant no. 254627 and 294402. We would also like to thank the staff and women of the Chingford study. Research in the UK was supported in part by the Arthritis and Rheumatism Council, St Thomas’ Hospital Special Trustees and the Wellcome Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mullin, B.H., Prince, R.L., Dick, I.M. et al. Bone structural effects of variation in the TNFRSF1B gene encoding the tumor necrosis factor receptor 2. Osteoporos Int 19, 961–968 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0517-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0517-7