Abstract

Summary

This post-hoc analysis queried whether women experiencing fracture on denosumab indicates inadequate treatment response or whether the risk of subsequent fracture remains low with continuing denosumab. Results showed that denosumab decreases the risk of subsequent fracture and fracture sustained while on denosumab is not necessarily indicative of inadequate treatment response.

Introduction

This analysis assessed whether a fracture sustained during denosumab therapy indicates inadequate treatment response and if the risk of a subsequent fracture decreases with continuing denosumab treatment.

Methods

In FREEDOM, a clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of denosumab, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis were randomized to placebo or denosumab for 3 years. In the 7-year FREEDOM Extension, all participants were allocated to receive denosumab. Here we compare subsequent osteoporotic fracture rates between denosumab-treated subjects during FREEDOM or the Extension and placebo-treated subjects in FREEDOM.

Results

During FREEDOM, 438 placebo- and 272 denosumab-treated subjects had an osteoporotic fracture. Exposure-adjusted subject incidence per 100 subject-years was lower for denosumab (6.7) vs placebo (10.1). Combining all subjects on denosumab from FREEDOM and the Extension for up to 10 years (combined denosumab), 794 (13.7%) had an osteoporotic fracture while on denosumab. Of these, one or more subsequent fractures occurred in 144 (18.1%) subjects, with an exposure-adjusted incidence of 5.8 per 100 subject-years, similar to FREEDOM denosumab (6.7 per 100 subject-years) and lower than FREEDOM placebo (10.1 per 100 subject-years). Adjusting for prior fracture, the risk of having a subsequent on-study osteoporotic fracture was lower in the combined denosumab group vs placebo (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 0.59 [0.43–0.81]; P = 0.0012).

Conclusions

These data demonstrate that denosumab decreases the risk of subsequent fracture and a fracture sustained while on denosumab is not necessarily indicative of inadequate treatment response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although osteoporosis therapy decreases fracture risk, fracture can occur while on treatment but not necessarily representing an inadequate response to therapy. In appropriately selected subjects, approved osteoporosis medications reduce, but do not eliminate, the risk of fracture. Clinical trials of efficacious therapeutic agents invariably report fractures in subjects receiving active drug, as well as those receiving placebo [1,2,3,4]. Furthermore, it is also recognized that in treatment-naïve subjects (and also likely in subjects on therapy) a new fragility fracture greatly increases the risk of subsequent fracture [5, 6]. It is therefore expected that some fractures will occur in subjects receiving treatment for osteoporosis, similar to what is observed in other diseases, such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, where treatment decreases, but does not eliminate, the risk of major adverse cardiac events [7, 8].

It has been suggested that the occurrence of at least two incident fractures and/or reductions in bone mineral density (BMD) greater than the least significant change while receiving treatment for osteoporosis are evidence of an inadequate response to therapy [9,10,11]. In addition, inadequate response should also be considered in subjects who sustained only one fracture while bone markers and BMD have not responded as expected for a given treatment. Circumstances that might contribute to an inadequate response to therapy include an unrecognized secondary cause of skeletal fragility, poor adherence to therapy, malabsorption, vitamin D deficiency, or inadequate efficacy of the chosen treatment. However, fractures may occur despite effective treatment, since any bone will fracture when it is exposed to sufficient force.

In the Fracture REduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis every 6 Months (FREEDOM) study, an international, randomized, placebo-controlled 3-year trial, denosumab reduced the risk of new vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis [4]. In the FREEDOM Extension study, eligible women received denosumab therapy for up to 10 years, and fracture incidence remained low after up to 10 years of treatment [12,13,14,15,16].

In this analysis, we tested the hypothesis that women who fractured while on denosumab treatment had a lower risk of subsequent fracture while continuing on therapy compared with women who received placebo.

Materials and methods

Study design

This analysis is based on a placebo-controlled trial and its open-label extension. The first was FREEDOM, an international, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that has been previously described (Fig. 1) [4, 12]. In this study, eligible women were postmenopausal, 60–90 years old, with a lumbar spine or total hip BMD T-score less than − 2.5 at either site, but greater than or equal to − 4.0 at both locations. Eligible women could not have had any severe, or more than two moderate, vertebral fractures and were free of other secondary causes of bone loss. Randomization was 1:1 to subcutaneous placebo or 60 mg denosumab (Prolia®; Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) every 6 months for 3 years, with daily calcium (≥ 1 g) and vitamin D (≥ 400 IU) supplements.

FREEDOM and FREEDOM Extension study design. This analysis included women who had received ≥ 2 doses of investigational product (placebo or denosumab) during FREEDOM or the Extension, had an osteoporotic fracture (new vertebral, including clinical vertebral, or nonvertebral) while on treatment, and continued treatment post-fracture. Q6M = every 6 months; SC = subcutaneously

The second study, FREEDOM Extension, has also been previously described [16]. Eligible subjects for the Extension were women who completed the FREEDOM study 3-year visit and did not discontinue or miss more than one dose of investigational product in either the denosumab or placebo arm. In the Extension, all participants were scheduled to receive subcutaneous open-label 60 mg denosumab every 6 months (± 1 month) with daily calcium and vitamin D. The Extension duration was for up to 7 years, for a total of up to 10 years of denosumab treatment from the start of the FREEDOM study.

This post-hoc analysis compared subsequent osteoporotic fracture rates between women receiving denosumab during FREEDOM or the Extension with women receiving placebo during FREEDOM. Subsequent osteoporotic fracture was defined as a new vertebral fracture (including both radiographic and clinical vertebral fractures) or nonvertebral fracture that occurred after an initial on-study fracture in subjects who received at least two doses of investigational product (placebo or denosumab) during FREEDOM or two doses of denosumab during the Extension and who continued treatment post-fracture. Participants were evaluated in three groups: FREEDOM placebo, FREEDOM denosumab, and combined denosumab. The combined denosumab group included subjects from the FREEDOM trial who received denosumab, subjects from the Extension long-term group who received denosumab, and subjects from the Extension crossover group who switched to denosumab during the Extension. Multiple confirmed fractures with the same x-ray date (e.g., ulna and radius fractures) were counted as one fracture event. Nonvertebral fractures were reported and confirmed as they occurred throughout FREEDOM and the Extension. Vertebral fractures were confirmed from scheduled spine x-rays annually in FREEDOM and at years 2, 3, 5, and 7 in the Extension (i.e., years 5, 6, 8, and 10 from FREEDOM baseline). Clinical vertebral fractures were also confirmed from unscheduled spine x-rays throughout FREEDOM and the Extension.

Statistical methods

Subsequent fractures were analyzed as recurrent events using the stratified Cox and the Prentice-Williams-Petersen total time models with the robust variance estimation adjusting for prior fracture. The analysis was repeated in subgroups of subjects with or without prevalent vertebral fracture, defined at treatment baseline, without adjusting for prior fracture. Treatment-by-subgroup interaction was also assessed. Time-to-first subsequent fracture during treatment was depicted using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Follow-up for subsequent fractures started from the first incident osteoporotic fracture during treatment through end of treatment, defined as the earlier of 7 months after the last dose or the end of study. Fractures after the end of treatment were excluded. Specifically, in the FREEDOM placebo and FREEDOM denosumab groups, follow-up started from the first incident fracture in FREEDOM through the end of treatment in FREEDOM (maximum 3 years of follow-up). In the Extension long-term group, follow-up started from the first incident fracture in FREEDOM or the Extension through the end of treatment in the Extension (maximum 10 years of follow-up). In the Extension crossover group, follow-up started from the first incident fracture in the Extension through the end of treatment in the Extension (maximum 7 years of follow-up).

Results

During FREEDOM, 438 placebo- and 272 denosumab-treated subjects received at least two doses of investigational product, had an osteoporotic fracture, and remained on study post-fracture. The mean ages at first on-treatment fracture were 74.1 and 74.5 years for the placebo- and denosumab-treated subjects, respectively. Subject characteristics were generally balanced between the placebo- and denosumab-treated groups in the FREEDOM 3-year analysis.

After 3 years in FREEDOM, 23 of 3702 subjects (0.6%) in the denosumab group had multiple new vertebral fractures compared with 59 of 3691 subjects (1.6%) in the placebo group. The risk ratio (95% confidence interval) for this reduction in multiple vertebral fractures is 0.39 (0.24, 0.63). When all subjects on denosumab from FREEDOM and the Extension for up to 10 years were combined (the combined denosumab group), 794 had an incident osteoporotic fracture while on denosumab, with a mean age at first incident fracture of 76.5 years. Other baseline characteristics for these subjects were similar to those observed in the FREEDOM 3-year analysis, except the expected longer treatment duration prior to first fracture and follow-up duration after the first fracture (Table 1).

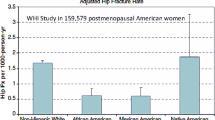

Of the placebo- and denosumab-treated subjects with an incident osteoporotic fracture in FREEDOM, 54 (12.3%) and 24 (8.8%) subjects, respectively, had one or more subsequent fractures in these groups. The exposure-adjusted subsequent fracture rate was 10.1 per 100 subject-years for placebo-treated subjects vs 6.7 per 100 subject-years for denosumab-treated subjects (Table 2; hazard ratio, HR [95% confidence interval, CI]: 0.65 [0.41–1.03]; P = 0.0685; Fig. 2). Of the subjects in the combined denosumab group, one or more subsequent fractures occurred in 144 (18.1%) subjects, with an exposure-adjusted subsequent fracture rate of 5.8 per 100 subject-years, similar to the rate observed in the FREEDOM denosumab group (Table 2). The risk of having a subsequent on-study osteoporotic fracture was lower in the combined denosumab group than in the FREEDOM placebo group (HR 0.59 [95% CI 0.43–0.81]; P = 0.0012; Fig. 2).

The median time to subsequent fracture since the first incident fracture was 1.0 year for the FREEDOM placebo group, 0.8 years for the FREEDOM denosumab group, and 1.9 years for the combined denosumab group. The difference between the time to first subsequent fracture between the combined denosumab vs placebo group subjects was significant with a log rank P value = 0.0045; Fig. 3).

A majority of subjects who had subsequent osteoporotic fractures had only one subsequent fracture: 90.7% (49 of 54 subjects) in the FREEDOM placebo group, 91.7% (22 of 24 subjects) in the FREEDOM denosumab group, and 89.6% (129 of 144 subjects) in the combined denosumab group. Vertebral fracture was the most common subsequent fracture across groups; a greater proportion of subjects in the FREEDOM placebo group (72.2%; 39 of 54) experienced these fractures compared with the FREEDOM denosumab (29.2%; 7 of 24) group and the combined denosumab (48.6%; 70 of 144) group. The second most common subsequent fracture location was the forearm, sustained by 4 of 54 (7.4%) subjects in the FREEDOM placebo group, 5 of 24 (20.8%) subjects in the FREEDOM denosumab group, and 29 of 144 (20.1%) subjects in the combined denosumab group (Table 3).

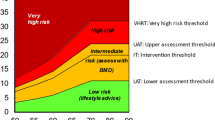

The effect of denosumab treatment on the reduction of subsequent fracture risk after an on-study fracture was significantly greater in subjects with baseline vertebral fractures compared with subjects without baseline vertebral fracture (P value = 0.0347). The refracture rate in subjects with baseline vertebral fracture in the FREEDOM placebo group was 17.4 per 100 subject-years vs 7.8 per 100 subject-years in the combined denosumab group (HR [95% CI]: 0.41 [0.26–0.65]; p < 0.0001). The refracture rate in subjects without baseline vertebral fracture in the FREEDOM placebo group was 6.8 per 100 subject-years vs 4.9 per 100 subject-years in the combined denosumab group from the Extension (HR [95% CI]: 0.81 [0.50–1.30]; P = 0.373; Fig. 4).

Subjects with at least one on-study osteoporotic fracture event were further analyzed to determine whether there were any differences in baseline characteristics between subjects with and without subsequent fractures. Baseline age and age at first incident fracture were similar between these groups. Overall, among the subjects who suffered an incident fracture, those with a subsequent fracture were more likely to have had a baseline vertebral or osteoporotic fracture than were those who did not suffer a subsequent fracture (Table 4).

The rates of subsequent vertebral and nonvertebral fractures were also determined for subjects with subsequent fractures. For subjects with subsequent osteoporotic fractures in the FREEDOM placebo group, 31.5% had both initial and subsequent vertebral fractures, 7.4% had an initial vertebral fracture followed by a subsequent nonvertebral fracture, 40.7% had an initial nonvertebral fracture followed by a subsequent vertebral fracture, and 20.4% had both initial and subsequent nonvertebral fractures. For subjects with subsequent osteoporotic fractures in the combined denosumab group, 21.5% had both initial and subsequent vertebral fractures, 10.4% had an initial vertebral fracture followed by a subsequent nonvertebral fracture, 27.1% had an initial nonvertebral fracture followed by a subsequent vertebral fracture, and 41.0% had both initial and subsequent nonvertebral fractures (Table 5).

Discussion

In this analysis, refracture rates were lower in subjects who received denosumab compared with subjects who received placebo, both among those with and without a baseline vertebral fracture. However, in subjects without baseline vertebral fracture, the size of the denosumab treatment effect was smaller compared with subjects with baseline vertebral fracture, and it did not reach statistical significance. Of note, in subjects without prevalent vertebral fracture in FREEDOM, subjects receiving denosumab had lower fracture rates (1.7%) compared with subjects receiving placebo (5.2%); risk ratio (95% confidence interval) 0.31 (0.22, 0.44), indicating that denosumab is effective in subjects without prevalent vertebral fracture [17]. These data indicate that subjects with a greater risk of fracture benefit most from continuous treatment with denosumab. Fracture risk after an initial fracture event is relatively high, even in subjects receiving denosumab treatment (6.7 per 100 subject-years in the FREEDOM denosumab and 5.8 per 100 subject-years in the combined denosumab groups) although this risk is lower compared with the FREEDOM placebo group (10.1 per 100 subject-years). These data give assurance that, if continuous denosumab treatment is administered for up to 10 years, the subsequent fracture rate remains much lower than that observed in subjects not receiving active treatment after sustaining a fracture. Furthermore, there is evidence that discontinuation of denosumab returns subjects to their pretreatment fracture risk within a year or two [18, 19].

A persistent question remains in the treatment of osteoporosis regarding a comprehensive definition of inadequate response to therapy and when and whether the term “treatment failure” applies to subjects receiving treatment for osteoporosis [9,10,11]. A subject may be considered to have an inadequate response to therapy if he or she has one fracture with decreases in BMD or two (or more) fractures. The role of bone remodeling markers and BMD measurements in combination with the number of fractures contributes to an overall assessment of the subject which the clinician should use in clinical decision making.

Determining when a treatment for osteoporosis is suboptimal or inadequate remains a challenge; therefore, an ongoing evaluation of the efficacy of treatment, including consideration of a change in therapy, should be conducted throughout the course of treatment. No treatment completely eliminates fracture risk, and a single fracture in the absence of a decrease in BMD may not necessarily indicate an inadequate response to therapy. Unfortunately, it is impossible to know unequivocally whether a treatment is optimal. Clinical judgment of the treating physician is required in order to determine optimal future therapy in a subject after an on-treatment fracture event.

In the FREEDOM study, subjects with a baseline vertebral fracture who suffered an incident fracture were at the highest risk of subsequent fracture. In this high-risk subgroup, there was an even greater reduction in on-study subsequent fracture rates in subjects continuing on, or switching to, denosumab in the Extension. This suggests that subjects at high risk for fracture are those who benefit the most from continued treatment with denosumab, likely because of their higher baseline fracture risk.

Limitations of our study include the generation of data from a post-hoc subgroup analysis. Also, the placebo group crossed over to denosumab therapy after 3 years, leaving no placebo comparator during the Extension study. Follow-up time for the placebo-treated subjects was therefore limited to a maximum of 3 years, whereas follow-up time for the combined denosumab subjects could be up to 10 years. Furthermore, the number of subjects with subsequent fractures was fairly small, particularly in the FREEDOM placebo group, which limits the precision of estimates, particularly regarding vertebral vs nonvertebral fracture rates. Median post-first fracture follow-up duration was longer in subjects in the FREEDOM denosumab group (1.31 years) vs subjects in the FREEDOM placebo group (1.06 years), which changes the baseline characteristics and the length of exposure to subsequent fracture risk. Finally, 57 subjects (47 placebo-treated and 10 denosumab-treated) discontinued from the study (and treatment) at the time of first fracture in FREEDOM. Most occurred at the end of FREEDOM and were not included due to lack of follow-up in the FREEDOM analysis. Baseline characteristics for these subjects were similar, both between treatment groups and between those who did not discontinue therapy after first fracture (data not shown).

Our data demonstrate that denosumab decreases the risk of subsequent fracture, and a fracture sustained while on denosumab is not necessarily indicative of inadequate response to therapy. Continuing denosumab therapy appears to be a safe and valid clinical option in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. These data may help guide clinicians in choosing the optimal treatment for subjects who have had fractures while receiving denosumab.

References

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC et al (1996) Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 348(9041):1535–1541

Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Cummings SR, Hue TF, Lippuner K, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z, Martinez RLM, Tan M, Ruzycky ME, Su G, Eastell R (2012) The effect of 3 versus 6 years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res 27(2):243–254

Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, Vukicevic S, Zanchetta JR, de Villiers TJ, Constantine GD, Chines AA (2008) Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res 23(12):1923–1934

Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR et al (2009) Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 361(8):756–765

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA 3rd, Berger M (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15(4):721–739

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P et al (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35(2):375–382

Turnbull F (2003) Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet 362(9395):1527–1535

Duell PB, Santos RD, Kirwan BA, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Kastelein JJP (2016) Long-term mipomersen treatment is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 10(4):1011–1021

Diez-Perez A, Gonzalez-Macias J (2008) Inadequate responders to osteoporosis treatment: proposal for an operational definition. Osteoporos Int 19(11):1511–1516

Diez-Perez A, Olmos JM, Nogues X, Sosa M, Diaz-Curiel M, Perez-Castrillon JL et al (2012) Risk factors for prediction of inadequate response to antiresorptives. J Bone Miner Res 27(4):817–824

Diez-Perez A, Adachi JD, Agnusdei D, Bilezikian JP, Compston JE, Cummings SR et al (2012) Treatment failure in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 23(12):2769–2774

Papapoulos S, Chapurlat R, Libanati C, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Czerwinski E et al (2012) Five years of denosumab exposure in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from the first two years of the FREEDOM Extension. J Bone Miner Res 27(3):694–701

Bone HG, Chapurlat R, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Czerwinski E, Krieg MA et al (2013) The effect of three or six years of denosumab exposure in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from the FREEDOM Extension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(11):4483–4492

Ferrari S, Adachi JD, Lippuner K, Zapalowski C, Miller PD, Reginster JY, Törring O, Kendler DL, Daizadeh NS, Wang A, O’Malley CD, Wagman RB, Libanati C, Lewiecki EM (2015) Further reductions in nonvertebral fracture rate with long-term denosumab treatment in the FREEDOM open-label extension and influence of hip bone mineral density after 3 years. Osteoporos Int 26(12):2763–2771

Papapoulos S, Lippuner K, Roux C, Lin CJ, Kendler DL, Lewiecki EM et al (2015) The effect of 8 or 5 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the FREEDOM Extension study. Osteoporos Int 26(12):2773–2783

Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Chapurlat R, Cummings SR, Czerwiński E, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Kendler DL, Lippuner K, Reginster JY, Roux C, Malouf J, Bradley MN, Daizadeh NS, Wang A, Dakin P, Pannacciulli N, Dempster DW, Papapoulos S (2017) 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 5(7):513–523

McClung MR, Boonen S, Torring O, Roux C, Rizzoli R, Bone HG et al (2012) Effect of denosumab treatment on the risk of fractures in subgroups of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 27(1):211–218

Cummings SR, Ferrari S, Eastell R, Gilchrist N, Jensen JB, McClung M, Roux C, Törring O, Valter I, Wang AT, Brown JP (2018) Vertebral Fractures After Discontinuation of Denosumab: A Post Hoc Analysis of the Randomized Placebo-Controlled FREEDOM Trial and Its Extension. J Bone Miner Res 33(2):190-198

Brown JP, Roux C, Torring O, Ho PR, Beck Jensen JE, Gilchrist N et al (2013) Discontinuation of denosumab and associated fracture incidence: analysis from the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) trial. J Bone Miner Res 28(4):746–752

Acknowledgements

The authors thank James Ziobro (funded by Amgen Inc.) for providing medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Amgen Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

DL Kendler: Received research grants from Amgen Inc., Eli Lilly, Astellas, and AstraZeneca; consulting fees from Amgen Inc. and Eli Lilly; and honoraria from Amgen Inc., Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Merck.

A Chines and A Wang: Employees of and stockholders in Amgen Inc.

ML Brandi: Received honoraria from Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, and Kyowa Kirin; received academic grants and/or was a speaker for Abiogen, Alexion, Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Kirin, MSD, NPS, Servier, Shire, and SPA; served as a consultant to Alexion, Bruno Farmaceutici, Kyowa Kirin, Servier, and Shire.

S Papapoulos: Received consulting fees or lecture fees as an advisory group member or speaker from Amgen Inc. and Merck & Co. Received consulting fees as an ad hoc consultant from Axsome, Gador, and UCB. Received consulting fees as an advisory group member from Radius Health. Received speaking fees from Teva.

EM Lewiecki: Received consulting fees or grants as a member of a medical advisory board or study investigator from/for Amgen Inc., Merck & Co., Eli Lilly, and Radius.

J-Y Reginster: Received consulting fees or paid advisory boards from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Radius Health, and Pierre Fabre. Received lecture fees when speaking at the invitation of sponsor from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Cniel, and Dairy Research Council (DRC). Received grant support (all through institution) from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Cniel, and Radius Health.

M Muñoz Torres: Received lecture fees from Lilly and consulting fees as a member of a medical advisory board member from Amgen Inc.

HG Bone: Received consulting fees from Amgen Inc., Merck, Radius, and Shire. Received lecture fees from Amgen Inc. and Shire. Received research grants as an investigator from Amgen Inc., Merck, and Shire. Received fees as a data safety monitoring board member from Grunenthal.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kendler, D.L., Chines, A., Brandi, M.L. et al. The risk of subsequent osteoporotic fractures is decreased in subjects experiencing fracture while on denosumab: results from the FREEDOM and FREEDOM Extension studies. Osteoporos Int 30, 71–78 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4687-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4687-2