Abstract

Human activities have greatly increased the input of reactive nitrogen species into the environment and disturbed the balance of the global N cycle. This imbalance may be offset by bacterial denitrification, an important process in maintaining the ecological balance of nitrogen. However, our understanding of the activity of mixotrophic denitrifying bacteria is not complete, as most research has focused on heterotrophic denitrification. The aim of this study was to investigate substrate preferences for two mixotrophic denitrifying bacterial strains, Acidovorax delafieldii and Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis, under heterotrophic, autotrophic or mixotrophic conditions. This complex analysis was achieved by simultaneous identification and quantification of H2, O2, CO2, 14N2, 15N2 and 15N2O in course of the denitrification process with help of cavity-enhanced Raman spectroscopic (CERS) multi-gas analysis. To disentangle electron donor preferences for both bacterial strains, microcosm-based incubation experiments under varying substrate conditions were conducted. We found that Acidovorax delafieldii preferentially performed heterotrophic denitrification in the mixotrophic sub-experiments, while Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis preferred autotrophic denitrification in the mixotrophic incubation. These observations were supported by stoichiometric calculations. The results demonstrate the prowess of advanced Raman multi-gas analysis to study substrate use and electron donor preferences in denitrification, based on the comprehensive quantification of complex microbial gas exchange processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global nitrogen cycle is a central biogeochemical cycle and crucial for life on earth. The significance of nitrogen to the biosphere and cellular life is indisputable; however, our fundamental knowledge of the microorganisms and enzymatic processes that transform nitrogen into its various oxidation states is still evolving. Different microbial processes are responsible for converting and balancing atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) and reactive and thus bioavailable nitrogen species in the biogeosphere [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Recent human activities unbalanced the nitrogen cycle as the burning of fossil fuels and the application of fertilizers heavily increased the input of reactive nitrogen to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [1, 2]. The resulting imbalance and accumulation of reactive nitrogen are harmful for both nature and humans. It can cause eutrophication, acidification and a loss in biodiversity and can lead to severe diseases in humans (e.g. methemoglobinemia) [1,2,3,4]. Denitrification is an important process in maintaining the ecological balance of nitrogen, as it converts reactive nitrogen to N2 gas, removing reactive nitrogen from hydrosphere and geosphere and releasing N2 into the atmosphere. Although denitrification was thought to be exclusively performed by prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), eukaryotic organisms such as fungi and foraminifera also mediate this process and collectively play an important role in the global biogeochemical nitrogen cycle [5, 7,8,9]. In denitrifying bacteria, the reactive species nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) are transformed to N2 via several enzymatic reactions. A key to understand the current status of the nitrogen cycle is to what extent denitrification is influenced and can keep up with increasing availability of its substrate nitrate [1, 2]. Over the last decades, much attention has been paid to assess denitrification rates in a broad range of habitats [1,2,3,4], and denitrifying bacteria have been isolated from several ecosystems and were further investigated under laboratory conditions [5]. However, the effect of the type and availability of electron donors on the denitrifying process and denitrifying communities is still poorly understood [10, 11].

Denitrification is a four-step process transforming nitrate into N2 in sub-oxic and anoxic environments. The process is catalysed by several enzymes responsible for the different steps [5, 6].

If denitrification is coupled to a heterotrophic lifestyle (later referred to as “heterotrophic denitrification”), an organic carbon compound is needed as electron donor and carbon source. A general equation showing substrate conversion and production in heterotrophic denitrification is as follows [12]:

With x = 4/3 a + 1/3 b − 2/3 c

y = 2/3 a + 1/6 b − 1/3 c

z = 2/3 a + 2/3 b − 1/3 c

In contrast to this, denitrification coupled to a chemolithoautotrophic lifestyle (later referred to as “autotrophic denitrification”) uses carbon dioxide or bicarbonate as sole carbon source, as the organisms can convert it into organic carbon compounds themselves via CO2 fixation. Hydrogen, reduced iron or sulphur species are common electron donors in autotrophic denitrification [13,14,15,16]. Autotrophic denitrifying bacteria can prevail in organic carbon-limited ecosystems, utilizing inorganic electron donors such as hydrogen [17,18,19]. Oligotrophic groundwater is one type of habitat in which usually only a small amount of organic carbon is available. Under these conditions, chemolithoautotrophic lifestyles linked to denitrification are likely to become more competitive [20]. These autotrophic processes themselves and the biomass built up by chemolithoautotrophic primary production can also serve as a source of organic carbon for other biota and potentially support more complex food webs [21, 22].

Using hydrogen as electron donor, reactions taking place in denitrification are as follows [13]:

∆G°: −240 kJ mol−1 [23]

Thus, five molecules of hydrogen are needed to completely reduce two molecules of nitrate to one molecule of nitrogen. Along with that, protons are consumed.

Microbes that can thrive on organic as well as inorganic carbon as carbon source are called mixotrophs, which also applies to a large number of denitrifying taxa. Depending on substrate availability, denitrification by these organisms can be linked to either an autotrophic or a heterotrophic lifestyle. In a truly mixotrophic lifestyle, the denitrifying bacteria use the inorganic electron donor for energy generation but use the organic compound as carbon source [24,25,26].

For a detailed analysis of denitrification processes and preferential substrate utilization, monitoring concentration changes of gases such as N2, N2O, CO2 and O2 is a prerequisite. Moreover, if hydrogen is used as electron donor in autotrophic denitrification, its consumption also needs to be tracked. Usually, isotopically labelled reactive nitrogen sources (typically 15N-nitrate) are used to unambiguously determine the amount of N2 and intermediate products like N2O produced during denitrification. In addition, labelled carbon sources can be used to determine the fate of the carbon utilized by the bacteria. Thus, the concentration changes of (15)N2, (15)N2O, (13)CO2, H2 and O2 have to be observed for a comprehensive investigation of the denitrification process and substrate uses. Consequently, monitoring the consumption of electron donors and electron acceptors and generation of products and by-products requires a quantitative analysis of headspace gases with sufficient time resolution. This analysis should cover a wide concentration range with high sensitivity and selectivity, allowing, e.g., the discrimination between 15N2 produced from 15NO3− in the denitrification process and 14N2 present in the measuring setup.

In order to follow changes in the suite of gases (N2, N2O, CO2 and O2), a selective multi-gas analysis is needed. Raman spectroscopy is an emerging analytical technique [27,28,29]. Due to the low sensitivity of conventional Raman scattering, elaborated enhancement techniques based on optical cavities [30, 31] and hollow fibres [32,33,34] were recently developed and applied in several environmental gas experiments [35, 36]. Various gases can be detected in parallel due to the substance-specific spectral position of the Raman bands and no gases are consumed, enabling continuous in situ measurements [37,38,39]. Thus, Raman spectroscopy is ideally suited to investigate metabolic processes, such as denitrification. Concentration changes of complex gas mixtures including isotopically labelled gases can be monitored.

In this study, we used cavity-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (CERS) to investigate substrate use and substrate preference of two mixotrophic denitrifying hydrogenotrophic bacterial strains Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 and Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1, which are representative of denitrifiers in oligotrophic groundwater at the CZE (Critical Zone Exploratory) Hainich, Germany [40, 41]. Our goals were (i) to compare denitrification activity and growth of the two strains under heterotrophic, autotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions; (ii) to identify which electron donor was preferentially used under mixotrophic conditions; and (iii) to evaluate the suitability of CERS to get a comprehensive insight into the microbial transformation processes in these incubations.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, media and incubation conditions

Two bacterial strains were used in incubation experiments under denitrifying conditions with either hydrogen or organic electron donors. Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 was isolated from oligotrophic oxic groundwater from the Hainich CZE using a traditional gelrite-shake dilution approach. In brief, groundwater (50 μL) was inoculated into Hungate tubes containing 20 mL of nitrate-thiosulfate-carbonate (NTC) mineral medium [40] with 0.5% Gelrite under a gas atmosphere of 80% N2, 10% CO2 and 10% H2 and incubated under dark conditions at 15 °C. After 4 weeks, bacterial colonies developed in the semisolid medium were picked with sterile Pasteur pipettes and inoculated into Gelrite-free NTC mineral media. Incubations were carried out at 15 °C in the dark for a period of 1 month followed by a repeated process for 26 consecutive transfers with alternate semisolid and liquid NTC mineral medium. Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 DSM 2082 was obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ). All incubations were carried out in 120 mL serum bottles with 60-mL medium, sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and aluminum crimps.

For the microcosm experiment, A. delafieldii strain 16 was grown at 15 °C in modified ATCC medium 1246 with the following composition: 1.5 g L−1 KH2PO4, 1.5 g L−1 Na2HPO4 * 2 H2O, 0.1 g L−1 NH4Cl, 0.5 g L−1 MgSO4 * 7 H2O, 0.1 g L−1 CaCl2 * 2 H2O, 0.5 g L−1 MgCl2 * 6 H2O, 0.01 g L−1 MnCl2, 0.01 g L−1 FeCl3, 10 μM CuCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, vitamin solution [DSMZ 461 Mineral medium (Nagel and Andreesen): http://www.dsmz.de] (5 mL L−1) and trace element solution [DSMZ 461 Mineral medium (Nagel and Andreesen): http://www.dsmz.de] (1 mL L−1) per 1-L medium.

Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 was grown at 27 °C in DSMZ medium 81 (mineral medium for chemolithoautotrophic growth).

For the setup of each microcosm experiment, a preculture of each strain was set up in triplicate 120 mL serum vials. Cells were grown for 1 week at 15 °C (A. delafieldii strain 16) or 3 days at 27 °C (H. taeniospiralis strain 2K1) using the mineral media described above with 3 mmol L−1 (A. delafieldii strain 16) or 2 mmol L−1 NaNO3 (98% 15N) (H. taeniospiralis strain 2K1) and 3 mmol L−1 acetate or 1 mmol L−1 mannitol, respectively. Precultures were harvested by centrifugation in sterile 50 mL centrifuge tubes at 4000 * g and 15 °C for 6 min and washed twice with the respective mineral medium (without nitrate or carbon source) used for each strain. Subsequently, cell pellets were resuspended in mineral medium and were used to inoculate the denitrification microcosm experiments to an initial OD (600 nm) of 0.002.

For A. delafieldii strain 16, NaNO3 (98% 15N) was added to a final concentration of 3 mmol L−1. For heterotrophic and mixotrophic incubation conditions, sodium acetate (13C2H3NaO2) was added to a final concentration of 3 mmol L−1. The serum bottles for heterotrophic growth conditions were flushed with a gas mixture of 10% CO2 and 90% Ar (argon) to establish a defined headspace. For incubations under mixotrophic and autotrophic conditions, the headspace was composed of 10% CO2, 20% H2 and 70% argon. The sample bottles were incubated at 15 °C in the dark.

To the sample bottles of H. taeniospiralis strain 2K1, NaNO3 (98% 15N) was added to a final concentration of 2 mmol L−1. For growth under heterotrophic and mixotrophic conditions, mannitol was added to a final concentration of 1 mmol L−1. For growth under mixotrophic conditions, nitrate was replenished to a final concentration of 2 mmol L−1 after 160 and 209 h of incubation. Incubations were flushed with 10% CO2 and 90% argon for heterotrophic incubation conditions and with 10% CO2, 50% H2 and 40% argon for mixotrophic and autotrophic incubation conditions to establish the headspace. Sample bottles were incubated at 30 °C in the dark.

Raman spectroscopic gas analysis

Headspace gas analysis was performed using cavity-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (CERS). As described previously [42], an optical power build-up cavity with highly reflective mirrors was used to enhance the intensity of the laser diode (λ = 650 nm, Plaser = 50 mW) by several orders of magnitude up to 100 W. This enhancement of the laser power enabled the measurement of the gas concentrations between about 100 ppm and 100%. The sample gas was passed through this cavity and both pressure and temperature were recorded via sensors integrated into the spectrometer. Gas pre-treatment was not necessary, and no gases were consumed during the measurement. Thus, continuous measurements in a closed cycle were possible.

A robust calibration of the spectrometer could be realized due to the linear relationship between Raman scattering intensity and concentration. A spectrum of pure Raman-inactive argon was first acquired, which was used for background correction in subsequent measurements. Afterwards, spectra of the pure gases, which were expected in the experiment (H2, CO2, 13CO2, 15N2O, 15N2, O2, N2), were taken and further used as reference spectra. For concentration calculation, a multilinear regression using the full set of reference spectra and the measured spectrum was applied. This evaluation method basically expresses the measured spectrum as the sum of the weighted reference spectra, which results in weighting factors of the single gases. These weighting factors are proportional to the volumetric mixing ratio of the single gases.

Gas analysis setup

The measurement setup for the headspace analysis is shown in Fig. 1. Before and in between measurements, the setup was flushed with the Raman-inactive gas argon until no Raman peaks were visible anymore. Then, the sample was connected to the setup and a closed measurement cycle was established. The gases were measured for 5 min while being constantly circulated. Complete mixing of argon in the measurement setup and the headspace was realized in less than 1 min. As the exact volume of the measurement setup (40 mL) and the headspace (60 mL) were known as well as the temperature and the pressure in the system, the original concentration of analysed gases in the bottle headspace could be calculated.

Gas analysis setup for the denitrification experiments. A closed cycle between the sample and the Raman spectrometer was established for measurements, in which the sample headspace could be cycled (V1 and V4 closed, V2 and V3 open). Argon was connected to flush the measurement cycle in between measurements using MFCs (mass flow controllers); in this case, V1 and V4 are open and V2 and V3 are closed

As hydrogen can diffuse very easily, a correction for diffusion was used here. For each measurement time point, the difference between the control and replicate samples was calculated. This was done under the assumption that all samples of one time point have lost a comparable amount of hydrogen due to diffusion. The control samples lose hydrogen only due to diffusion, while the replicate samples lose hydrogen due to diffusion and denitrification. Thus, the correct amount of hydrogen used in denitrification is the difference between control and replicate samples.

Liquid medium analysis

After measurement of headspace gases, Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 cultures were centrifuged at 20,000 * g and 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and frozen at −20 °C for later analysis of nitrate and nitrite. Optical density measurements could not be performed for this bacterial strain due to the flocculation type growth behaviour in the liquid medium.

Immediately after the headspace measurement of Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1, 1.5 mL of the medium was removed for OD measurement. The samples were measured (Jasco UV/VIS/NIR, V-670, wavelength 600 nm) using pure medium as a reference. Additionally, 10 mL medium was transferred into 15 mL Falcon tubes, centrifuged at 5000 rpm (Herolab UniCen MR) for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new 15 mL Falcon tube and was frozen at −20 °C until further analysis for nitrate, nitrite and mannitol.

Concentrations of nitrate and nitrite in the incubations were determined by colorimetric assays using the salicylate method [43] and the Griess method [44], respectively. For the Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain K21 incubations, no reliable determination of nitrate could be achieved in presence of hydrogen using the respective method.

Mannitol analysis was performed on GC-MS, for a detailed description, see Supplementary Information (ESM) - Methods. A strong matrix effect was observed resulting in much lower than expected values. As for nitrate, no reliable mannitol concentrations could be obtained in the presence of H2.

Results and discussion

Cavity-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (CERS) is ideally suited for the monitoring of the denitrification process. This is demonstrated by an exemplary spectrum, where all components of the sample headspace (except Raman-inactive argon) are spectrally well resolved and can be analysed simultaneously (see ESM Fig. S1).

The two characteristic peaks of the Fermi dyad of CO2 can be seen at \({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_{-}=1285\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) and \({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_{+}=1388\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) [45]. For 13CO2, these peaks are at \({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_{-}=1265\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) and \({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_{+}=1370\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) overlap with 12CO2 in the spectrum if both gases are present in the headspace at the same time. Using linear combinations of calibration spectra of 12CO2 and 13CO2, the concentrations of both isotopologues can be gained from the Raman spectra [46, 47]. H2 has rotational bands at \(\overset{\sim }{\nu }\ \left({S}_0(1)\right)=587\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\), \(\overset{\sim }{\nu }\ \Big({S}_0(2)=814\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) and \(\overset{\sim }{\nu }\ \Big({S}_0(3)=1034\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) [48]. 15N2 at \({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_0=2252\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) [36] can be clearly discriminated from 14N2 (\({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_0=2331\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\)) [45], which enters the measurement setup together with O2 (\({\overset{\sim }{\nu}}_0=1556\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\)) [45] via diffusion in small amounts. No additional compounds like the intermediate product 15N2O (\(\overset{\sim }{\nu }=1265\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) and \(\overset{\sim }{\nu }=2155\ {\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\)) [36] could be seen in the spectra (for the example spectrum, see ESM Fig. S1).

Denitrification and electron donor preference of Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16

Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 was isolated from groundwater samples from the Hainich CZE. Other strains of this bacterial species have been described as mixotrophic bacteria with differing properties, especially regarding denitrification [49]. To assess the metabolic capabilities of the strain from the Hainich CZE, Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 was cultured under three different growth conditions to investigate the growth dynamics under heterotrophic, autotrophic and mixotrophic conditions. In the experiments under heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions, concentrations of 15N2 and 13CO2 in the headspace increased with time, indicating complete denitrification to N2 by oxidation of the organic electron donor. Under autotrophic growth conditions, no bacterial growth or substrate conversion was observed. Since the initial isolation and subsequent testing for denitrification activity, the strain had apparently lost its ability to use hydrogen as electron donor in denitrification.

The use of nitrate and hydrogen as well as the production of gaseous end products could be followed closely for the experiments under heterotrophic and mixotrophic conditions (Fig. 2). Nitrate was depleted in the liquid phase after 65 h, when all the nitrite, which had built up after around 50 h of incubation, had been consumed, too (Fig. 2A and B). At that time point, the maximum 15N2 headspace concentration (about 1200 μmol L−1) was detected (Fig. 2A and B). After that, no further increase was seen, suggesting complete conversion of nitrate to dinitrogen gas. The large standard deviation for nitrate at 40 h in Fig. 2A and B can be explained by slightly different growth dynamics of the bacteria in the three individual replicate incubation flasks which were sampled at this time point. During the exponential phase, nitrate concentrations decreased rapidly within just 20 h. Consequently, minor differences in the progress of bacterial activity within each flask resulted in large differences in nitrate concentrations between the replicates. The concentration change in nitrate and dinitrogen gas was mirrored by 13CO2 concentration changes in the gas phase, where about 700 μmol L−1 was produced (Fig. 2A and B) from the utilization of 13C-labelled acetate as organic electron donor. Hydrogen gas was available as alternative electron donor in the incubations under mixotrophic conditions; however, only minor concentration changes of hydrogen were observed (Fig. 2A).

Concentration changes of selected gases in the headspace and of 15NO3−, 15NO2− and ammonium (NH4+) in the liquid phase of Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 cultures under different incubation conditions over time. A Mixotrophic conditions, both H2/CO2 and 13C-acetate are available as substrates. B Heterotrophic conditions, 13C-acetate is available as substrate. Depicted values are averaged measurements from three replicate culture flasks with standard deviation

Concentration changes for 13CO2 (Fig. 3A) and 15N2 (Fig. 3B) were compared for heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions. Concentration changes as well as time course are very similar for both gases (Fig. 3). Similar final concentrations were reached for 15N2 (Fig. 3B) and 13CO2 (Fig. 3A) at the end of the incubations. Nitrogen production rates were calculated based on the near-linear concentration increase between 27 and 66 h (mixotrophic incubation) and 42 and 66 h (heterotrophic incubation). For the incubation under heterotrophic conditions, a denitrification rate of 42.38 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 was achieved, for the mixotrophic incubation only 28.27 μmol N2 L−1 h1 even though nitrogen production seems to have started a little earlier than for the heterotrophic incubation.

Comparison of concentration changes over time for A 13CO2 and B 15N2 under heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions for Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16. For both gases, concentration changes and time course are very similar for the two incubations. Depicted values are averaged measurements from three replicate culture flasks with standard deviation

To determine whether heterotrophic or autotrophic denitrification prevailed under mixotrophic conditions, we performed stoichiometric calculations based on the added substrates and measured headspace gas concentrations. The adapted Eq. 1 for heterotrophic denitrification using acetate as organic substrate and sodium nitrate is as follows:

A final 15N2 concentration of 1200 μmol L−1 indicated that out of the original 3 mmol nitrate L−1, 2.4 mmol L−1 had been converted to N2. The missing fraction of 0.6 mmol L−1 might have been consumed as nitrogen source for biomass build-up by assimilatory nitrate reduction. However, this explanation is unlikely, due to the fact that the medium also contained ammonium which serves as nitrogen source and was not depleted in the course of the incubations. Consequently, the reason remains unclear why not the entire nitrate was retrieved as N2 in the final gas phase. Liquid-phase measurements showed that no nitrate or nitrite remained in the medium, providing further support for a complete denitrification process under both heterotrophic and mixotrophic conditions.

The reduction of 2.4 mmol L−1 nitrate by denitrification would have required the consumption of 1.5 mmol L−1 of the added 3 mmol L−1 of 13C-actetate and the production of 3 mmol L−1 13CO2. In the gas phase, we could measure an increase of 0.7 mmol L−1 13CO2, which means that 2.3 mmol L−1 remained in the liquid phase. This can be explained with the carbonate buffer system (see Eq. 8) active in the incubations. In denitrification, protons are consumed, and alkalinity increases in the reduction step of nitrite to NO (see Eq. 4), which in turn leads to carbon dioxide being dissolved and dissociated to keep the buffer in equilibrium.

Denitrification and electron donor preference of Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1

Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 is a mixotrophic bacterium which is known to only use hydrogen as electron donor in autotrophic metabolism [50]. To investigate whether Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 prefers to utilize organic or inorganic electron donors when grown under mixotrophic conditions, different incubation experiments were established. Mannitol served as electron donor and carbon source for heterotrophic growth under heterotrophic and mixotrophic conditions, while hydrogen acted as electron donor for autotrophic and mixotrophic growth under autotrophic and mixotrophic conditions.

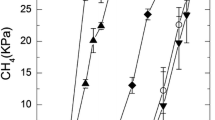

For Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1, complete denitrification was performed under all three different growth conditions (Fig. 4). The detected 15N2 headspace concentrations were in good agreement with the expected values based on the amount of 15N-nitrate added to the medium. For growth and denitrification under autotrophic conditions, 15N2 concentrations were lower than for the other two experimental setups during the exponential phase after 63 h incubation (Fig. 4A). 15N2O was not detected in the headspace and no significant amounts of nitrite (maximum of 142 μmol L−1 at 63 h in the autotrophic incubation) were detected in the medium in any incubation (Fig. 4B–D). For the experiment under heterotrophic conditions, 15N2 production coincided with an increase in CO2 concentrations and nitrate was depleted after 63 h, when 15N2 concentrations had increased strongly (Fig. 4B).

Concentration changes of headspace gases and NO3− and NO2− in the liquid medium over time for denitrification by Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 under three different growth conditions. A 15N2 concentrations. B All gases as well as nitrate and nitrite, heterotrophic incubation. C All gases and nitrite, autotrophic conditions. D All gases and nitrite, mixotrophic conditions. Depicted values are averages with standard deviations

Even though measured mannitol concentrations were much lower than expected due to a strong matrix effect, the general behaviour can be deduced. Mannitol concentrations decreased over the course of the experiment with the decrease being the largest, when N2 production rates were the highest. Mannitol was not completely depleted but reached a plateau at about 0.5 μmol L−1 (see ESM Fig. S2). A small increase in H2 concentrations was also visible (Fig. 4B). In the experiment under autotrophic conditions, 15N2 production was paralleled by a decrease in H2 concentrations (Fig. 4C). CO2 concentrations did not change over the course of the measurements (Fig. 4C). Under mixotrophic growth conditions, 15N2 was produced while H2 concentrations decreased, and CO2 remained at a stable level (Fig. 4D).

Nitrogen production rates were calculated for Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 based on the near-linear concentration changes during the exponential phase. For the heterotrophic incubation, a rate of 27.95 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 was achieved (between 39 and 63 h) and for the autotrophic incubation 13.69 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 (between 39 and 90 h). Due to the additional doses of nitrate, three rates could be calculated for the mixotrophic incubation. These rates increased over time in the experiment and are the highest found in this experiment. 24.75 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 (between 22 and 63 h), 34.67 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 (between 158 and 183 h) and 34.69 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 (between 209 and 238.5 h) were calculated. These nitrogen production rates are similar to those of Acidovorax delafieldii (42.38 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 for the heterotrophic incubation and 28.27 μmol N2 L−1 h−1 for the mixotrophic incubation) and are in the same range as those reported in Kumar et al. 2018 (243 μmol L−1 day−1, which corresponds to 10.125 μmol L−1 h−1, [40]).

For each measured sample, the optical density (OD) was determined (Fig. 5). Under heterotrophic conditions, OD values increased more rapidly over time, suggesting that biomass built up much faster than in the other two incubations (Fig. 5), which is in accordance with other experiments reported in literature [13, 51, 52]. While incubations under heterotrophic and autotrophic conditions were stopped after 180 h when nitrate was depleted, additional nitrate was added to the incubations under mixotrophic conditions, allowing denitrification to continue and OD values and thus bacterial biomass still to increase (Figs. 4A and 5).

To gain more insight which electron donor or carbon source was preferentially used under mixotrophic growth conditions, stoichiometric calculations were conducted for the Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis experiments. The calculations are based on the added substrates and the measured headspace concentrations. When mannitol is used as organic substrate in heterotrophic denitrification, the equation shown in “Introduction” (Eq. 1) is as follows [12]:

A 15N2 concentration of about 0.75 mmol L−1 was measured in the gas phase, which accounts for ¾ of the added nitrate in the medium (1.5 mmol L−1 of 2 mmol L−1). Similar to the experiment with Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16, it remains unclear whether part of this nitrate was used as nitrogen source for biomass build-up. For heterotrophic denitrification, an increase in 15N2 concentrations by 0.75 mmol L−1 would be accompanied by an increase in CO2 concentrations in the headspace by 1.730 mmol L−1 and a decrease in mannitol concentrations in the medium by 0.290 mmol L−1 from the original concentration of 1 mmol L−1. As explained for Acidovorax delafieldii, alkalinity increases in denitrification (Eq. 9), which leads to a decrease in CO2 concentrations to keep the carbonate buffer in equilibrium (Eq. 8). For the incubation under heterotrophic conditions, an increase of approximately 1.2 mmol L−1 in CO2 concentrations was observed. Thus, part of the CO2 produced during heterotrophic denitrification remained in the liquid phase. For incubations under mixotrophic and autotrophic sub-experiments, we did not observe an increase in CO2.

Mannitol was used in heterotrophic denitrification, but due to the high matrix effect influencing the GC-MS measurements, mannitol concentration values are not suited for rigorous calculations. However, the general behaviour can be deduced.

For hydrogenotrophic denitrification, 5 mmol of hydrogen is used up to produce 1 mmol of N2. For the observed increase in 15N2 concentrations by 0.750 mmol L−1, this would correspond to a reduction in the concentration of hydrogen by 3.750 mmol L−1. This fits very well with the measured hydrogen concentrations, where Δ c(H2) values were up to 3.787 mmol L−1 in the mixotrophic and autotrophic sub-experiments with an average value of 3.067 ± 0.632 mmol L−1 at the end of the experiment.

Taking these stoichiometric calculations and the measured data into account, it can be concluded that in the denitrification experiments under heterotrophic and autotrophic conditions, heterotrophic and autotrophic denitrification was performed, respectively. For the mixotrophic incubation, the case is not quite straightforward. A clear decrease in hydrogen concentrations in a similar range as for the autotrophic incubation was observed. For CO2, no concentration changes were observed for the mixotrophic and autotrophic incubations, but an obvious increase was measured for the heterotrophic incubation. Finally, OD values for the mixotrophic and autotrophic incubations were very similar with the mixotrophic values being slightly higher than the autotrophic ones. But for 15N2 concentrations, the mixotrophic data is more similar to the heterotrophic than to the autotrophic data, especially at 63 h. For the 15N2 production rates, the same observation was made.

Departing from these observations, it can be concluded that autotrophic denitrification took place in the mixotrophic incubations and hydrogen was preferred over mannitol as electron donor. The observed differences from the purely autotrophic incubations suggest a boost by mannitol as carbon source which cannot be confirmed by mannitol measurements for this setup.

To get a better overview of the amount of electron donors available to the bacteria, the concentration of hydrogen in the liquid medium was calculated using Henry’s law. The calculated hydrogen concentrations are by a factor of 1000 smaller than the maximum concentrations of mannitol, as the maximum dissolved hydrogen concentration was about 0.004 mmol L−1. This makes the preference of hydrogen over mannitol as electron donor even more remarkable, as literature usually speaks of facultative autotrophs [50], which is to say that they can perform autotrophic denitrification when the substrate for heterotrophic denitrification is not available. The heterotrophy is preferred over the autotrophy, because it is reported to be more energy efficient [53]. This contrasts with our results, where autotrophic denitrification was performed in the incubation under mixotrophic conditions.

Comparison of substrate usage preferences

Stoichiometric calculations based on added substrates and produced gases showed that Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 used the organic electron donor and carbon source in the sub-experiment under mixotrophic conditions. Thus, it can be concluded that Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 performed heterotrophic denitrification in the mixotrophic incubation. This is as in accordance with literature, where heterotrophic denitrification is described as thermodynamically preferred over autotrophic denitrification [53]. As the trait for using hydrogen in denitrification was obviously lost in between preliminary experiments and the main experiment, no results were achieved for autotrophic denitrification.

For Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1, fully heterotrophic denitrification was only carried out in the sub-experiment under heterotrophic growth conditions. In contrast, hydrogen was preferred as electron donor over mannitol in the sub-experiment under mixotrophic growth conditions. This means that the growth was supported by autotrophic denitrification. However, it is likely that mannitol has been used to a small extent in the mixotrophic incubation to enhance denitrification rates, even though H2 usage and growth measured via OD were more similar to the autotrophic incubations. Jewell et al. explained, that for mixotrophic growth, mainly heterotrophic denitrification takes place, but chemolithoautotrophy is used in combination with heterotrophy to gain advantage over purely heterotrophic growth [54].

In our experiments with Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1, the autotrophic substrates are preferred over the heterotrophic ones, when offered at the same time. Autotrophic denitrification was performed, even though the concentration of the heterotrophic electron donor mannitol was 1000-fold higher than the concentration of dissolved hydrogen. Mannitol seems to have been used to boost denitrification rates compared to the purely autotrophic incubations.

Our lab experiments allow the clear determination of substrate preferences and growth characteristics of denitrifying bacteria. The transfer to natural systems is associated with uncertainties, as the complex environmental conditions cannot be mimicked in the laboratory. Furthermore, there is a high degree of diversity in bacteria performing denitrification in each ecosystem [5]. Every bacterial strain has optimum growth and performance conditions, which are adapted to the environment they were isolated from, but which can also change in prolonged incubation series. Sophisticated methods are needed to disentangle the complexity of metabolic processes in nature.

Conclusion

CERS multi-gas analysis was applied for the comprehensive analysis of the headspace of two microbial cultures performing denitrification. Substrate consumption and gas production in denitrification were followed closely throughout the experiment. The gases H2, (13)CO2, (15)N2, 15N2O and O2 were simultaneously quantified. The ability for sensitive quantification of hydrogen and nitrogen is highlighted. The presence of unknown or unexpected gases could be excluded, as no additional peaks were detected in the Raman spectra. The denitrifying bacteria produced 15N2 from 15N-labelled nitrate. The stable isotope 15N was used to distinguish the nitrogen produced via denitrification from atmospheric nitrogen. The Raman peaks of 14N2 and 15N2 are well separated in the spectra; thus, both nitrogen species could be quantified, and diffusion effects could be separated from microbial processes (see ESM Fig. S1).

Substrate preference could be assigned for the separate experiments and heterotrophic and autotrophic denitrification could be distinguished. Heterotrophic and autotrophic denitrification could be assigned as preferred strategy to the mixotrophic incubation for Acidovorax delafieldii strain 16 and Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1, respectively.

The demonstrated method offered the possibility to investigate the electron donor and carbon source preference of other facultative autotrophs in more detail using CERS headspace gas analysis in combination with stoichiometric calculations. Improved knowledge about metabolic activities in bacteria, kinetics and preferential substrate use can lead to a better understanding of dynamics of denitrification performed by natural microbial communities, allowing a more detailed understanding and better predictions of N cycling processes under different environmental conditions. This can help in assessing which substrates are likely to be used in natural environments and whether purely autotrophic, heterotrophic or rather mixotrophic processes will dominate. An example is the oligotrophic groundwater in Hainich National Park, which is poor in organic carbon and would call for autotrophic denitrification [22, 40]. But a mixotrophic lifestyle, where denitrification rates are enhanced by small amounts of organic carbon available to the bacteria, can also be imagined when the results of the experiments with Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis strain 2K1 shown here are considered. These results do not apply to all bacterial strains, as can be seen from the comparison of denitrification performed by Acidovorax delafieldii and Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis, and substrate preferences can differ greatly. This demonstrates the great versatility of denitrifying bacteria and requires a closer investigation of mixotrophic denitrification and substrate preference in denitrification. Cavity-enhanced Raman spectroscopy shows great prospects for the investigation of electron donor and carbon source preferences in denitrification.

References

Galloway JN, Dentener FJ, Capone DG, Boyer EW, Howarth RW, Seitzinger SP, et al. Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry. 2004;70(2):153–226.

Fowler D, Coyle M, Skiba U, Sutton MA, Cape JN, Reis S, et al. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2013;368(1621):20130164.

Galloway JN, Aber JD, Erisman JW, Seitzinger SP, Howarth RW, Cowling EB, et al. The nitrogen cascade. AIBS Bull. 2003;53(4):341–56.

Gruber N, Galloway JN. An earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature. 2008;451(7176):293–6.

Zumft WG. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61(4):533–616.

Knowles R. Denitrification. Microbiol Rev. 1982;46(1):43.

Kobayashi M, Matsuo Y, Takimoto A, Suzuki S, Maruo F, Shoun H. Denitrification, a novel type of respiratory metabolism in fungal mitochondrion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(27):16263–7.

Philippot L. Denitrifying genes in bacterial and archaeal genomes. BBA-Gene Structure and Expression. 2002;1577(3):355–76.

Glock N, Schönfeld J, Eisenhauer A, Hensen C, Mallon J, Sommer S. The role of benthic foraminifera in the benthic nitrogen cycle of the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone. Biogeosciences. 2013;10:4767–83.

Li P, Wang Y, Zuo J, Wang R, Zhao J, Du Y. Nitrogen removal and N2O accumulation during hydrogenotrophic denitrification: influence of environmental factors and microbial community characteristics. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(2):870–9.

Calderer M, Martí V, De Pablo J, Guivernau M, Prenafeta-Boldú FX, Viñas M. Effects of enhanced denitrification on hydrodynamics and microbial community structure in a soil column system. Chemosphere. 2014;111:112–9.

Koeve W, Kähler P. Heterotrophic denitrification vs autotrophic anammox-quantifying collateral effects on the oceanic carbon cycle. Biogeosciences. 2010;7:2327–37.

Karanasios K, Vasiliadou I, Pavlou S, Vayenas D. Hydrogenotrophic denitrification of potable water: a review. J Hazard Mater. 2010;180(1):20–37.

Ghafari S, Hasan M, Aroua MK. Effect of carbon dioxide and bicarbonate as inorganic carbon sources on growth and adaptation of autohydrogenotrophic denitrifying bacteria. J Hazard Mater. 2009;162(2):1507–13.

Vasiliadou I, Pavlou S, Vayenas D. A kinetic study of hydrogenotrophic denitrification. Process Biochem. 2006;41(6):1401–8.

Mansell BO, Schroeder ED. Hydrogenotrophic denitrification in a microporous membrane bioreactor. Water Res. 2002;36(19):4683–90.

Bradley P, Chapelle F. Arsenate inhibition of denitrification in nitrate contaminated sediments. Soil Biol Biochem. 1993;25(10):1459–62.

Nelson DC, Hagen KD. Physiology and biochemistry of symbiotic and free-living chemoautotrophic sulfur bacteria. Amer Zool. 1995;35(2):91–101.

Ottley C, Davison W, Edmunds W. Chemical catalysis of nitrate reduction by iron (II). Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1997;61(9):1819–28.

Küsel K, Totsche KU, Trumbore SE, Lehmann R, Steinhäuser C, Herrmann M. How deep can surface signals be traced in the critical zone? Merging biodiversity with biogeochemistry research in a central German Muschelkalk landscape. Front Earth Sci. 2016;4:32.

Herrmann M, Rusznyák A, Akob DM, Schulze I, Opitz S, Totsche KU, et al. Large fractions of CO2-fixing microorganisms in pristine limestone aquifers appear to be involved in the oxidation of reduced sulfur and nitrogen compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(7):2384–94.

Herrmann M, Geesink P, Yan L, Lehmann R, Totsche K, Küsel K. Complex food webs coincide with high genetic potential for chemolithoautotrophy in fractured bedrock groundwater. Water Res. 2020;170:115306.

Blodau C. Thermodynamic control on terminal electron transfer and methanogenesis. Aquatic redox chemistry: ACS Publications; 2011. p. 65–83.

Matin A. Organic nutrition of chemolithotrophic bacteria. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1978;32(1):433–68.

Oh S, Yoo Y, Young J, Kim I. Effect of organics on sulfur-utilizing autotrophic denitrification under mixotrophic conditions. J Biotechnol. 2001;92(1):1–8.

Bock E, Schmidt I, Stüven R, Zart D. Nitrogen loss caused by denitrifying Nitrosomonas cells using ammonium or hydrogen as electron donors and nitrite as electron acceptor. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163(1):16–20.

Frosch T, Knebl A, Frosch T. Recent advances in nano-photonic techniques for pharmaceutical drug monitoring with emphasis on Raman spectroscopy. Nanophotonics. 2020;9(1):19–37.

Domes C, Domes R, Popp J, Pletz MW, Frosch T. Ultrasensitive detection of antiseptic antibiotics in aqueous media and human urine using deep UV resonance Raman spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 2017;89(18):9997–10003.

Frosch T, Popp J. Structural analysis of the antimalarial drug halofantrine by means of Raman spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(4):041516.

Salter R, Chu J, Hippler M. Cavity-enhanced Raman spectroscopy with optical feedback cw diode lasers for gas phase analysis and spectroscopy. Analyst. 2012;137(20):4669–76.

Jochum T, von Fischer JC, Trumbore S, Popp J, Frosch T. Multigas leakage correction in static environmental chambers using sulfur hexafluoride and Raman spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 2015;87(21):11137–42.

Jochum T, Rahal L, Suckert RJ, Popp J, Frosch T. All-in-one: a versatile gas sensor based on fiber enhanced Raman spectroscopy for monitoring postharvest fruit conservation and ripening. Analyst. 2016;141(6):2023–9.

Yan D, Frosch T, Kobelke J, Bierlich J, Popp J, Pletz MW, et al. Fiber-enhanced Raman sensing of cefuroxime in human urine. Anal Chem. 2018;90(22):13243–8.

Yan D, Domes C, Domes R, Frosch T, Popp J, Pletz MW, et al. Fiber enhanced Raman spectroscopic analysis as a novel method for diagnosis and monitoring of diseases related to hyperbilirubinemia and hyperbiliverdinemia. Analyst. 2016;141(21):6104–15.

Knebl A, Domes R, Yan D, Popp J, Trumbore S, Frosch T. Fiber-enhanced Raman gas spectroscopy for (18)O-(13)C-labeling experiments. Anal Chem. 2019;91(12):7562–9.

Keiner R, Herrmann M, Kusel K, Popp J, Frosch T. Rapid monitoring of intermediate states and mass balance of nitrogen during denitrification by means of cavity enhanced Raman multi-gas sensing. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;864:39–47.

Sieburg A, Jochum T, Trumbore SE, Popp J, Frosch T. Onsite cavity enhanced Raman spectrometry for the investigation of gas exchange processes in the Earth’s critical zone. Analyst. 2017;142(18):3360–9.

Jochum T, Fastnacht A, Trumbore SE, Popp J, Frosch T. Direct Raman spectroscopic measurements of biological nitrogen fixation under natural conditions: an analytical approach for studying nitrogenase activity. Anal Chem. 2017;89(2):1117–22.

Knebl A, Domes R, Wolf S, Domes C, Popp J, Frosch T. Fiber-enhanced Raman gas spectroscopy for the study of microbial methanogenesis. Anal Chem. 2020;92(18):12564–71.

Kumar S, Herrmann M, Blohm A, Hilke I, Frosch T, Trumbore SE, et al. Thiosulfate-and hydrogen-driven autotrophic denitrification by a microbial consortium enriched from groundwater of an oligotrophic limestone aquifer. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018;94(10):fiy141.

Kumar S, Herrmann M, Thamdrup B, Schwab VF, Geesink P, Trumbore SE, et al. Nitrogen loss from pristine carbonate-rock aquifers of the Hainich Critical Zone Exploratory (Germany) is primarily driven by chemolithoautotrophic anammox processes. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1951.

Frosch T, Keiner R, Michalzik B, Fischer B, Popp J. Investigation of gas exchange processes in peat bog ecosystems by means of innovative Raman gas spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 2013;85(3):1295–9.

DEV.1975. Deutsches Einheitsverfahren zur Wasser-, Abwasser- und Schlammuntersuchung. Physikalische, chemische, biologische und bakteriologische Verfahren, (1975).

Grasshoff K, Ehrhardt M, Kremling K. Methods of seawater analysis. Verlag Chemie Weinheim. Weinheim; 1983.

Fenner WR, Hyatt HA, Kellam JM, Porto S. Raman cross section of some simple gases. JOSA. 1973;63(1):73–7.

Keiner R, Gruselle MC, Michalzik B, Popp J, Frosch T. Raman spectroscopic investigation of 13CO 2 labeling and leaf dark respiration of Fagus sylvatica L. (European beech). Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;407(7):1813–7.

Jochum T, Michalzik B, Bachmann A, Popp J, Frosch T. Microbial respiration and natural attenuation of benzene contaminated soils investigated by cavity enhanced Raman multi-gas spectroscopy. Analyst. 2015;140(9):3143–9.

Flora F, Giudicotti L. Complete calibration of a Thomson scattering spectrometer system by rotational Raman scattering in H 2. Appl Opt. 1987;26(18):4001–8.

Willems A, Falsen E, Pot B, Jantzen E, Hoste B, Vandamme P, et al. Acidovorax, a new genus for Pseudomonas facilis, Pseudomonas delafieldii, E. Falsen (EF) group 13, EF group 16, and several clinical isolates, with the species Acidovorax facilis comb. nov., Acidovorax delafieldii comb. nov., and Acidovorax temperans sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1990;40(4):384–98.

Willems A, Gillis M. Hydrogenophaga. Bergey’s manual of systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. 2015:1–15.

Ergas SJ, Reuss AF. Hydrogenotrophic denitrification of drinking water using a hollow fibre membrane bioreactor. J Water Supply Res T. 2001;50(3):161–71.

Soares M. Biological denitrification of groundwater. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2000;123(1–4):183–93.

Rezania B, Cicek N, Oleszkiewicz J. Kinetics of hydrogen-dependent denitrification under varying pH and temperature conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92(7):900–6.

Jewell TN, Karaoz U, Bill M, Chakraborty R, Brodie EL, Williams KH, et al. Metatranscriptomic analysis reveals unexpectedly diverse microbial metabolism in a biogeochemical hot spot in an alluvial aquifer. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:40.

Acknowledgements

We thank Falko Gutmann for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Nico Überschaar for mannitol analysis.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study is part of the Collaborative Research Centre AquaDiva (CRC 1076 AquaDiva) of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (project number 218627073). AB and SK received funding from the International Max-Planck Research School (IMPRS) “Global Biogeochemical Cycles”. Climate chambers to conduct experiments under controlled temperature conditions were financially supported by the Thüringer Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft und Digitale Gesellschaft (TMWWDG; project B 715-09075).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Published in the topical collection celebrating ABCs 20th Anniversary.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(PDF 253 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blohm, A., Kumar, S., Knebl, A. et al. Activity and electron donor preference of two denitrifying bacterial strains identified by Raman gas spectroscopy. Anal Bioanal Chem 414, 601–611 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-021-03541-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-021-03541-y