Abstract

We review the imaging findings of pediatric gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) using contemporary anatomic and molecular imaging techniques. A low index of suspicion can result in significant delays in diagnosis of pediatric GEP-NETs. A multimodality imaging approach, using both anatomic and functional imaging, is essential in the diagnosis, staging, and surveillance of these potentially malignant tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neuroectodermal tumors arising from the neural crest, such as neuroblastomas, form a large proportion of childhood neoplasms. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) are a small subgroup of neural crest tumors whose imaging findings are not well described in children. These tumors arise from neuroendocrine cells found in the pancreas, the gut, and its derivatives including the bronchial tree. The term “neuroendocrine tumors” encompasses carcinoid tumors, islet cell tumors, and amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) tumors. Although these tumors can produce distinct clinical syndromes because of their secretory capacity, they are underdiagnosed in children, resulting in delays in detection [1, 2]. The small size of the primary tumor and its tendency to occur anywhere along the gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) system can make detection a challenge. Advances in anatomic imaging and incorporation of metabolic imaging techniques have led to improved detection of these tumors.

Since 1990, 13 patients 21 years of age or younger were seen at our hospital with a diagnosis of a GEP-NET. The primaries were located in the pancreas (n = 4), lung (n = 4), appendix (n = 1), thymus (n = 1) and middle ear (n = 1), and in two patients the tumor was primary unknown. Six patients had functional tumors and were symptomatic for several months to 5 years (mean 2 years) with symptoms including diarrhea, peptic ulcer disease, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Metastases were present in 50% of these patients by the time a GEP-NET was diagnosed. Two of the three patients with pulmonary NET tumors presented with recurrent pneumonia. One patient with an unsuspected NET developed carcinoid crisis after resection of the tumor and required intensive care management. One patient had a history of a familial disorder, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, predisposing to NET.

Discussion

Classification

GEP-NETs have traditionally been classified into two groups: (1) carcinoids, which are subdivided by their origin into tumors of the foregut (lung, thymus, stomach, duodenum), midgut (jejunum, ileum, appendix, right colon), and hindgut (left colon, rectum); and (2) pancreatic tumors [3]. A more prognostically useful classification was proposed by the World Health Organization in 2000: well-differentiated NETs, which show benign behavior (group 1a); well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC), which are characterized by low-grade malignancy (group 1b); and poorly differentiated NEC of high-grade malignancy (group 2) [4].

Based on their clinical features, these tumors can be functional or nonfunctional. Functional tumors have clinical symptoms caused by hypersecretion of hormones such as gastrin, while nonfunctional tumors can produce clinically silent hormones such as pancreatic polypeptide. These tumors often produce more than one hormone, and the functional tumors are named according to the hormone responsible for the clinical syndrome, for example gastrinoma causing Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and insulinoma causing hypoglycemic syndrome. NETs can either be sporadic or occur as part of familial syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) I and II, VHL syndrome and neurofibromatosis type I (NF-I).

Imaging approach

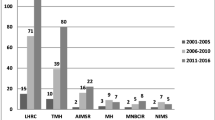

There is limited information in the pediatric literature regarding the imaging findings of NETs. Most of the information regarding imaging of these tumors is obtained from adult studies. The quoted diagnostic performance of different imaging modalities in various studies is highly variable depending on local expertise, different stages of technology development, and the imaging protocols used. A multimodality imaging approach using both anatomic and molecular imaging is essential for detection, staging, and surveillance of these tumors [5].

Anatomic imaging

Multidetector CT

Multidetector CT (MDCT) has been shown to have an accuracy of 92% and 96% for the detection of primary tumor and metastasis, respectively [6]. The advantages of MDCT include high temporal and spatial resolution, acquisition of isotropic data resulting in high-quality reformatted images, and bolus-tracking capability resulting in precise timing of the scan. However, it is imperative that the radiologist select appropriate imaging parameters (tube current, gantry rotation time, kilovoltage, table speed and detector configuration) to achieve a balance between image quality and radiation exposure [7]. Although in general multiphase examinations should be avoided in children to keep radiation exposure as low as is reasonably achievable (ALARA), optimal evaluation of NETs requires dual-phase imaging. Images are obtained during arterial and portal venous phases of enhancement after administration of intravenous contrast agent at a rate of 3–5 ml/s (Fig. 1). The appropriate delay after contrast agent injection and before scanning will vary with the size of the patient. In an average teenager, there will be a delay of approximately 25 s for the arterial phase and a delay of 60 to 70 s for visualization of the portal vein. This aids detection of NETs, which often demonstrate early enhancement with washout during the portal venous phase because of their hypervascular nature. Visualization of mural masses can be improved by using water as an oral contrast agent. MDCT can also be used to perform small-bowel enteroclysis to detect small mural and luminal lesions of gut NETs [8].

A 6-year-old girl with history of abdominal pain and diarrhea for several months. Contrast-enhanced axial CT image in the arterial phase (a) demonstrates multiple enhancing liver lesions (arrows) that are difficult to discern on the portal venous phase (b) consistent with hypervascular metastases. Also note the thickening of the gastric folds due to elevated gastrin levels. Fine-needle aspiration of a liver lesion confirmed metastatic gastrinoma

MRI

MRI has the highest sensitivity in detecting liver metastasis [9]. Arterial phase images after contrast agent administration and fat-suppressed fast spin echo T2-W images are the most sensitive in detecting liver lesions because of their hypervascular nature (Fig. 2). For the detection of pancreatic lesions, MRI has been shown to have a sensitivity of 94%, with the tumor being most conspicuous on fat-saturated T1-W images [10].

A 14-year-old boy after resection of a bronchial NEC. Axial T1-W image (a) demonstrates a hypointense liver lesion that is moderately hyperintense on the T2-W image (b). Arterial phase image after gadolinium administration (c) shows intense early enhancement with wash-out to isointensity on the portal venous phase images (d), consistent with hypervascular metastasis

Sonography

Although traditional transabdominal US examinations have low sensitivity in detection of small tumors, contrast-enhanced, endoscopic, and intraoperative US examinations have been reported to have higher sensitivities in the detection of small lesions [9]. Endoscopic US with color Doppler imaging has been shown to have sensitivities in the range of 79–100% for the detection of small lesions in the pancreas head [11]. Intraoperative US examinations have also been shown to improve the accuracy of lesion detection to 97% in the pancreatic head (Fig. 3) [12].

A 21-year-old man with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease for 5 years and elevated gastrin levels of 5,258 pg/ml (normal range 0–100 pg/ml). Intraoperative US image shows a 3×3 cm hypoechoic mass in the pancreas (arrow) closely abutting the splenic vein (V). Surgical resection confirmed pancreatic gastrinoma

Molecular imaging

The overexpression of somatostatin receptors and the presence of amine uptake and storage mechanisms allows targeted molecular imaging of NETs using somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) and metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG), respectively. The sensitivity of octreotide and MIBG scintigraphy is known to range between 78% and 100% and 36% and 85%, respectively [13]. 111Indium diethylenetriaminepentaacetate (DTPA) octreotide is the most widely used radiopharmaceutical for SRS of NETs and is currently the modality of choice in the evaluation of these tumors (Fig. 4) [14]. Octreotide has high affinity for somatostatin receptors, especially subtype 2, resulting in good correlation between scintigraphic findings and the expression of somatostatin receptors on these tumors as determined by immunostaining. These receptors can also be targeted for radiotherapy with radiolabeled somatostatin analogues [14].

A 6-year-old girl with a history of abdominal pain and diarrhea for several months (same patient as in Fig. 2). SRS SPECT image (a) obtained 24 h after intravenous administration of indium 111 pentatreotide in the coronal plane shows multiple foci of increased uptake in the liver (arrowhead) with an intense focus inferior to the liver (arrow), which corresponds to the exophytic lesion arising from the pancreatic neck (arrow) seen on the coronal reformatted CT image (b). This is a surgically proven gastrinoma. c Photomicrograph of immunohistochemistry slide shows positive staining (brown) for somatostatin receptors

Positron emission tomography (PET) has the advantage of high sensitivity, reasonable resolution, and the ability to perform whole-body scans (Fig. 5). 18Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is the most widely used tracer but has limited sensitivity in detection of well-differentiated and slow-growing tumors [15]. PET using novel tracers such as 6-[fluoride-18] fluoro-levodopa (18F-DOPA), a catecholamine precursor, shows promise in the evaluation of NETs [16].

Fusion imaging

Coregistration of molecular and anatomic modalities with SPECT-CT or PET-CT can aid in accurate localization of disease and areas of physiologic uptake (Figs. 6 and 7). Fusion imaging with SPECT-CT has been shown to be more accurate than either SPECT or CT alone and resulted in management changes in 28% of patients in one series [17].

A 19-year-old male after resection of bronchial NEC 7 years previously. a Surveillance CT demonstrates expansion of the left sacral neural foramen by a soft-tissue mass (arrow). b FDG-PET demonstrates the lesion to be FDG avid raising the suspicion of tumor. Surgical resection confirmed metastasis to the left S1 nerve sheath

A 16-year-old boy after resection of pancreatic gastrinoma 7 years previously with recurrent symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. a, b Coregistered SRS SPECT and contrast-enhanced CT images allow accurate localization of radionuclide uptake to a paracaval lymph node (arrow) and a perigastric (arrowhead) lymph node, both of which are less than 1 cm in short axis. Also note multiple hepatic metastases with intense octreotide uptake

Common pediatric GEP-NETs by location

Appendiceal NETs

Appendiceal NETs are the most common pediatric GEP-NETs [2]. While appendiceal NETs in adults are generally incidentally detected, 78–97% of appendiceal NETs in children are associated with appendicitis (Fig. 8) [18–20]. In a series of 36 children with appendiceal carcinoids, the median age at diagnosis was 12.3 years, and three-fourths presented with acute appendicitis while the rest presented with chronic abdominal pain [21]. Although carcinoid syndrome has been reported in association with appendiceal NETs in adults, the largest series of these tumors in children failed to show any children with symptoms of carcinoid syndrome [18, 20]. These tumors occur primarily at the appendix tip and are generally less than 2 cm in size. The long-term prognosis is good, with metastatic disease being unusual in children with appendiceal NETs, as shown in two large series with a median follow-up of 10–26 years [18, 21]. However, appendiceal carcinoids with synchronous and metachronous adenocarcinoma of the colon have been reported, even in children [2, 18].

A 21-year-old female with a history of right lower quadrant pain for 6 days. a Contrast-enhanced axial CT image demonstrates a distended (13 mm) non-opacified appendix (arrow) with minimal periappendiceal stranding. b Gross specimen of the appendix demonstrates obliteration of the lumen by the pale tumor that extends through the wall into the serosa near the tip (arrow)

Gastrointestinal NETs

GEP-NETs in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract are less common in children. Duodenal NETs arise from gastrin cells and tend to produce Zollinger-Ellison syndrome [22]. Duodenal carcinoids are most common in the proximal duodenum and present as early enhancing intraluminal polyps or mural masses [23]. Unlike duodenal NETs, jejunal and ileal NETs arise from the serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cells and can cause carcinoid syndrome. Serotonin production results in imaging findings of mesenteric desmoplasia, bowel kinking, elastic vascular sclerosis, and intestinal ischemia [8]. Ileal NETs might present with abdominal pain or diarrhea secondary to increased intestinal motility or obstruction secondary to intussusception. In the hindgut, the most common location of NETs is the rectum. Most of these tumors are nonfunctional, with rectal NETs having a better prognosis than NETs in other parts of the colon.

Hepatic NETs

The liver is a common site of extra-appendiceal NETs in children. In a series of 13 children with extra-appendiceal NETs, the liver was the second most common site of disease (5 of 13 children) [1]. It is unclear whether these tumors represent true primary hepatic neoplasms or metastases from asymptomatic occult NETs. Like the primary NETs, liver lesions are hypointense on T1-W images, hyperintense on T2-W images, and demonstrate arterial phase enhancement.

Pancreatic NETs

Pancreatic NETs account for approximately 30% of pancreatic tumors in patients younger than 20 years. While insulinomas are the most common in adults, gastrinomas are more common in children. Hypersecretion of gastrin by gastrinomas causes recurrent or ectopic peptic ulcers (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), or malabsorption diarrhea. Most gastrinomas are solitary lesions located in the gastrinoma triangle, formed by the junction of the pancreatic neck and body, the second and third parts of the duodenum, and the junction of the cystic and common bile ducts. Nongastrinoma neuroendocrine tumors can occur in any part of the pancreas [24]. Metastases are present in 60–80% of patients at initial diagnosis of gastrinoma, with the liver and lymph nodes being the most common sites of metastatic disease [25]. Most neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas are hypointense on fat-suppressed T1-W images, moderately hyperintense to the pancreas on T2-W fat-suppressed images, and show moderately intense early enhancement [24]. Patients with familial NETs, such as MEN and VHL disease, might present with multiple tumors with the majority being nonfunctional (Fig. 9).

A 21-year-old female with history of VHL disease. a, b Contrast-enhanced axial CT images during arterial phase demonstrate an enhancing mass in the body of the pancreas (arrow). A second mass located in the uncinate process (arrowhead) adjacent to the portal vein was missed on initial reading. c, d FDG-PET axial images demonstrate two metabolically active foci in the pancreas, confirmed to be nonfunctional NETs at surgery

Pulmonary NETs

Pulmonary NETs are the most common extra-appendiceal NETs in children [1]. They are also the most common primary pulmonary neoplasm of childhood, accounting for between 16% and 80% of malignant lung tumors in this population [1, 26]. Children with these tumors tend to present with wheezing and atelectasis, in addition to the classic adult triad of cough, hemoptysis, and obstructive pneumonitis [27]. Most present in late adolescence, though these tumors have been reported in children as young as 3 years [28]. Patients might be symptomatic for approximately a year prior to diagnosis [27]. Bronchial carcinoids in children tend to arise in the main, lobar, or segmental bronchi, in regions of bronchial bifurcation. They typically present as hilar or perihilar masses, with associated findings of endobronchial obstruction such as air-trapping, atelectasis, mucus-plugging, and obstructive pneumonitis (Fig. 10). The mass is usually a well-defined round or ovoid homogeneously enhancing lesion with slightly lobulated margins. The intense enhancement of the tumor is helpful for differentiating the mass from adjacent postobstructive parenchymal changes (Fig. 10). Calcification might be present in up to 30% at histologic analysis. Carcinoid syndrome is unusual with bronchial NETs unless they have metastasized to the liver or are large in size with systemic drainage [29]. Intraoperatively, these tumors can release vasoactive mediators such as 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), resulting in carcinoid crisis characterized by bronchospasm, hypotension, acidosis, and ventricular tachycardia. If the diagnosis of a NET is considered preoperatively, the life-threatening complication of carcinoid crisis can be prevented by pretreatment with octreotide [30].

A 20-year-old man with a history of “asthma” and recurrent pneumonia for 2 years. a Chest radiograph demonstrates right base consolidation and right pleural effusion with an in-dwelling chest tube. b Contrast-enhanced axial CT image demonstrates an enhancing right hilar mass (arrow) with right lower lobe obstructive pneumonitis. c Lung section at lobectomy demonstrates a fleshy circumscribed mass (arrow) with a small endobronchial and larger extraluminal component. The lung parenchyma is filled with cheesy purulent material (arrowhead) secondary to obstructive pneumonitis

Thymic NETs

Thymic NETs tend to be more aggressive than other foregut tumors and often have metastatic disease at initial presentation [9]. Not much is known about thymic carcinoids in children; adult studies have shown that while bronchial carcinoids are malignant in about 26% of patients, thymic carcinoids can be malignant in about 80% of patients [31]. They can present with local symptoms (such as superior vena cava syndrome), can be incidentally detected on radiographs, and can produce Cushing syndrome (Fig. 11).

A 17-year-old female with an incidentally detected anterior mediastinal mass. a, b Axial contrast-enhanced CT images after biopsy demonstrate an infiltrating soft-tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum with enlarged pretracheal, subcarinal and hilar lymph nodes, and pleural studding (arrow). c Bone window image demonstrates multiple sclerotic lesions in the vertebral body, sacrum, and iliac wings consistent with metastatic disease. d Photomicrograph of H&E-stained section shows round cells with regular nuclei and salt-and-pepper chromatin. e, f Immunostaining is positive for the neuroendocrine tumor markers chromogranin (e) and synaptophysin (f)

Middle ear NETs

NETs can also occur in the middle ear cavity, which is a derivative of the first pharyngeal pouch of the foregut (Fig. 12). Typical presenting symptoms of middle ear NETs include hearing loss, aural fullness, and tinnitus. Physical examination might reveal a mass behind the tympanic membrane. The imaging and histologic characteristics of these tumors can mimic those of paragangliomas. Although middle ear NETs are typically low-grade malignancies that have an indolent course, there is a 22% risk of recurrence and 9% risk of metastatic disease [32].

Conclusions

A low index of suspicion for GEP-NETs in children combined with nonspecific clinical complaints can result in delay in the detection of these rare but treatable malignancies. A multimodality imaging approach using both anatomic and functional imaging is essential in the diagnosis, staging, and surveillance of these potentially malignant tumors in children.

References

Broaddus RR, Herzog CE, Hicks MJ (2003) Neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid and neuroendocrine carcinoma) presenting at extra-appendiceal sites in childhood and adolescence. Arch Pathol Lab Med 127:1200–1203

Spunt SL, Pratt CB, Rao BN et al (2000) Childhood carcinoid tumors: the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg 35:1282–1286

Tomassetti P, Migliori M, Lalli S et al (2001) Epidemiology, clinical features and diagnosis of gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumours. Ann Oncol 12 [Suppl 2]:S95–S99

Kloppel G, Perren A, Heitz PU (2004) The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: the WHO classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1014:13–27

Kaltsas G, Rockall A, Papadogias D et al (2004) Recent advances in radiological and radionuclide imaging and therapy of neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Endocrinol 151:15–27

Kumbasar B, Kamel IR, Tekes A et al (2004) Imaging of neuroendocrine tumors: accuracy of helical CT versus SRS. Abdom Imaging 29:696–702

Paterson A, Frush DP (2007) Dose reduction in paediatric MDCT: general principles. Clin Radiol 62:507–517

Horton KM, Kamel I, Hofmann L et al (2004) Carcinoid tumors of the small bowel: a multitechnique imaging approach. AJR 182:559–567

Rockall AG, Britto KE, Grossman AB et al (2004) Neuroendocrine tumours. Taylor and Francis, London

Thoeni RF, Mueller-Lisse UG, Chan R et al (2000) Detection of small, functional islet cell tumors in the pancreas: selection of MR imaging sequences for optimal sensitivity. Radiology 214:483–490

Rosch T, Lightdale CJ, Botet JF et al (1992) Localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. N Engl J Med 326:1721–1726

Grant CS (1999) Surgical aspects of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 28:533–554

Ezziddin S, Logvinski T, Yong-Hing C et al (2006) Factors predicting tracer uptake in somatostatin receptor and MIBG scintigraphy of metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med 47:223–233

Guillermet-Guibert J, Lahlou H, Pyronnet S et al (2005) Endocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Somatostatin receptors as tools for diagnosis and therapy: molecular aspects. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 19:535–551

Eriksson B, Bergstrom M, Sundin A et al (2002) The role of PET in localization of neuroendocrine and adrenocortical tumors. Ann N Y Acad Sci 970:159–169

Koopmans KP, de Vries EG, Kema IP et al (2006) Staging of carcinoid tumours with 18F-DOPA PET: a prospective, diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Oncol 7:728–734

Pfannenberg AC, Eschmann SM, Horger M et al (2003) Benefit of anatomical-functional image fusion in the diagnostic work-up of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:835–843

Moertel CL, Weiland LH, Telander RL (1990) Carcinoid tumor of the appendix in the first two decades of life. J Pediatr Surg 25:1073–1075

Corpron CA, Black CT, Herzog CE et al (1995) A half-century of experience with carcinoid tumors in children. Am J Surg 170:606–608

Ryden SE, Drake RM, Franciosi RA (1975) Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children. Cancer 36:1538–1542

Prommegger R, Obrist P, Ensinger C et al (2002) Retrospective evaluation of carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children. World J Surg 26:1489–1492

Cholewa D, Waldschmidt J, Hoffmann K et al (1997) A 7-year-old child with primary tumour localisation in the distal duodenum-new imaging procedures for an improved diagnosis. Eur J Pediatr 156:568–571

Levy AD, Taylor LD, Abbott RM et al (2005) Duodenal carcinoids: imaging features with clinical-pathologic comparison. Radiology 237:967–972

Semelka RC, Custodio CM, Cem Balci N et al (2000) Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: spectrum of appearances on MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 11:141–148

Zollinger RM, Ellison EC, O’Dorisio TM et al (1984) Thirty years’ experience with gastrinoma. World J Surg 8:427–435

Hancock BJ, Di Lorenzo M, Youssef S et al (1993) Childhood primary pulmonary neoplasms. J Pediatr Surg 28:1133–1136

Wang LT, Wilkins EW Jr, Bode HH (1993) Bronchial carcinoid tumors in pediatric patients. Chest 103:1426–1428

Moraes TJ, Langer JC, Forte V et al (2003) Pediatric pulmonary carcinoid: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol 35:318–322

Lack EE, Harris GB, Eraklis AJ et al (1983) Primary bronchial tumors in childhood. A clinicopathologic study of six cases. Cancer 51:492–497

Kinney MA, Warner ME, Nagorney DM et al (2001) Perianaesthetic risks and outcomes of abdominal surgery for metastatic carcinoid tumours. Br J Anaesth 87:447–452

Duh QY, Hybarger CP, Geist R et al (1987) Carcinoids associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Am J Surg 154:142–148

Ramsey MJ, Nadol JB Jr, Pilch BZ et al (2005) Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: clinical features, recurrences, and metastases. Laryngoscope 115:1660–1666

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Khanna, G., O’Dorisio, S.M., Menda, Y. et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in children and young adults. Pediatr Radiol 38, 251–259 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-007-0564-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-007-0564-4