Abstract

Purpose

The primary objective of this phase I dose-escalation study was to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of sunitinib plus pemetrexed in patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

Using a 3 + 3 dose-escalation design, patients received oral sunitinib qd by continuous daily dosing (CDD schedule; 37.5 or 50 mg) or 2 weeks on/1 week off treatment schedule (Schedule 2/1; 50 mg). Pemetrexed (300–500 mg/m2 IV) was administered q3w. At the proposed recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D), additional patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were enrolled.

Results

Thirty-five patients were enrolled on the CDD schedule and seven on Schedule 2/1. MTDs were sunitinib 37.5 mg/day (CDD/RP2D) or 50 mg/day (Schedule 2/1) with pemetrexed 500 mg/m2. Dose-limiting toxicities included grade (G) 5 cerebral hemorrhage, G3 febrile neutropenia, and G3 anorexia. Common G3/4 drug-related non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) at the CDD MTD included fatigue, anorexia, and hand–foot syndrome. G3/4 hematologic AEs included lymphopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. No significant drug–drug interactions were identified. Five (24%) NSCLC patients had partial responses.

Conclusions

In patients with advanced solid malignancies, the MTD of sunitinib plus 500 mg/m2 pemetrexed was 37.5 mg/day (CDD schedule) or 50 mg/day (Schedule 2/1). The CDD schedule MTD was tolerable and demonstrated promising clinical benefit in NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive or synergistic preclinical effects are observed when antiangiogenic agents are combined with chemotherapy [1–3]. In clinical trials, the addition of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) targeting monoclonal antibody, to chemotherapy, improved efficacy, compared with chemotherapy alone in patients with advanced, non-squamous, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [4, 5], and colorectal cancer [6]. Similarly, the combination of the chemotherapeutic agent pemetrexed with the antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), sunitinib, could potentially offer a therapeutic advantage over pemetrexed alone.

Pemetrexed (ALIMTA®), an inhibitor of multiple folate pathway enzymes, has demonstrated clinical activity in a broad range of solid tumors, including breast, colorectal, bladder, cervical, gastric, head and neck, and pancreatic cancers [7]. Pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin is approved as standard first-line treatment for mesothelioma and non-squamous, advanced NSCLC [8–10]. Single-agent pemetrexed is approved as second-line therapy for patients with non-squamous, advanced NSCLC, due to its comparable efficacy with docetaxel and favorable safety profile [11]. Pemetrexed is also approved as maintenance therapy, due to its demonstrated improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) versus best supportive care alone [12, 13]. However, overall response rates (ORRs) in the second-line NSCLC setting remain low (<10%) and treatment combinations with improved efficacy are needed [11–13].

Sunitinib (SUTENT®) is an oral antiangiogenic multitargeted TKI with nanomolar range potency inhibiting VEGF receptors (VEGFRs 1–3), platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs α and β), and other receptors [14]. It is effective in the treatment for renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and imatinib-resistant or -intolerant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) when administered once daily at 50 mg on a schedule of 4 weeks on treatment followed by 2 weeks off treatment (Schedule 4/2) [15–20]. Antitumor activity with sunitinib has also been demonstrated in patients with other solid malignancies, including NSCLC, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, sarcoma, thyroid cancer, and melanoma [21–23]. While the optimal dosing schedule for sunitinib has not been determined or directly compared in the clinical trial setting, both intermittent and continuous daily dosing (CDD) schedules have demonstrated similar efficacy and tolerability in patients with RCC, GIST, and NSCLC [22, 24–29].

As pemetrexed is active in a broad spectrum of tumors, combining pemetrexed with an antiangiogenic agent such as sunitinib may improve antitumor activity. Preclinical additive activity or synergy was demonstrated in NSCLC: sunitinib decreased tumor growth in NSCLC NCI-H460 xenograft models and pemetrexed enhanced its antitumor activity [2]. Based on preclinical synergy, and the single-agent clinical activity of both agents in NSCLC, we investigated the feasibility, tolerability, and early antitumor activity of the combination of pemetrexed and sunitinib in patients with advanced solid malignancies. This treatment combination was subsequently explored at the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) and schedule in an expanded cohort of patients with advanced NSCLC.

Patients and methods

Study population

Male or female patients, 18 years or older, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1 were considered for study entry into the original cohort. Patients were eligible if they had a diagnosis of a solid malignancy that was histologically or cytopathologically confirmed and refractory to standard therapy, or for which no standard therapy existed. Eligibility criteria included adequate organ function (including bone marrow, kidney, and liver), and a life expectancy of ≥12 weeks. In the NSCLC expansion cohort, previously treated and/or platinum refractory/intolerant patients with recurrent or advanced NSCLC of all histological subtypes were eligible for enrollment.

Patients were excluded if they had uncontrolled or symptomatic brain metastases, gross hemoptysis (≥5 mL per episode or ≥10 mL per day) within 4 weeks of study start, uncontrolled hypertension (>150/100 mmHg) despite standard antihypertensive agents, or cardiac disease, cerebrovascular accident or pulmonary embolism within 12 months of starting on study. Other exclusion criteria included National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 3.0) grade 3 hemorrhage within 4 weeks of treatment, ongoing cardiac dysrhythmias of grade ≥2, atrial fibrillation of any grade, prolongation of the QTc interval (>450 ms for men or >470 ms for women), or prior treatment with pemetrexed or sunitinib.

Study design and treatment

This open-label, multicenter, phase I trial (NCT00528619) conducted in the US and Canada investigated escalating doses of sunitinib plus pemetrexed in combination with serial patient cohorts. The primary end point was the determination of the toxicity profile to establish the MTDs of sunitinib administered in combination with pemetrexed in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Secondary end points included safety, pharmacokinetic (PK) profile, and preliminary antitumor activity of this combination.

Sunitinib was administered orally once daily on either the CDD schedule or 2 weeks on treatment followed by 1 week off treatment schedule (Schedule 2/1). Pemetrexed was administered once every 3 weeks (q3w). Planned dose cohorts followed a standard dose escalation 3 + 3 design of sunitinib (37.5 mg to 50 mg) and pemetrexed (300–500 mg/m2 IV), beginning with the CDD schedule. Each treatment cycle lasted 3 weeks, and patients could receive up to eight cycles of combination treatment. When discontinuations occurred for reasons other than treatment-related toxicity during the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) observation timeframe, patients were replaced. Patients who continued to receive clinical benefit were eligible to enter a continuation protocol with the combination or with sunitinib alone. At the discretion of the investigator, patients with progressive disease who were still benefiting from treatment (e.g., in the presence of isolated central nervous system progression) could also receive sunitinib or the treatment combination within the same continuation protocol. The MTD was defined as the highest dose cohort where 0/3 or ≤1/6 patients experienced a DLT, with the next highest dose having at least 2/3 or 2/6 patients who experienced a DLT. DLTs were defined as the occurrence during cycle 1 of grade 3 or 4 drug-related toxicities, including neutropenia (grade 3 with infection; grade 4 ≥ 7 days or febrile > 24 h), thrombocytopenia (grade ≥ 3 with bleeding or grade 4 ≥ 7 days), and any grade 3/4 non-hematologic toxicity ≥7 days or that resulted in a delay in administration of cycle 2 as scheduled. If the MTD on the CDD schedule was established at sunitinib 50 mg/day + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, the MTD on Schedule 2/1 was to be the same dose level without being formally tested. Provided that the CDD schedule MTD was established at sunitinib 37.5 mg/day + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or lower, the starting dose for Schedule 2/1 was to be the lowest non-tolerated dose on the CDD schedule. Depending on the doses of sunitinib determined to be tolerable on Schedule 2/1 and the CDD schedule, one cohort would be nominated for further exploration at the MTD to establish a proposed RP2D and schedule and expanded to enroll an additional 15 patients with locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC (the NSCLC expansion cohort).

Intra-patient dose reduction (relative to the lowest dose of the current cycle and at the discretion of the investigator) was permitted if a patient experienced a grade 3 or 4 toxicity considered attributable to either study drug, provided that criteria for patient withdrawal from study treatment were not met. Guidelines suggested reducing pemetrexed by an increment of 100 mg/m2 and reducing sunitinib daily dosing by 12.5 mg. If grade 3 or 4 toxicities recurred, patients could undergo further dose reduction in subsequent cycles up to a maximum of 2 dose reductions in any drug; the minimum dose for pemetrexed was 200 mg/m2 and for sunitinib was 25 mg daily. Assigned doses during the PK portion of the study (cycle 1 day 1 through cycle 2 day 2) were maintained when possible to allow for valid comparisons.

The investigator could delay sunitinib dosing for patients experiencing treatment-related toxicity, but it was recommended that patients requiring dose delay longer than 4 weeks in duration on either schedule were withdrawn. Pemetrexed was withheld if creatinine clearance was less than 45 mL/min and the decision for future dosing was then made by the investigator.

All patients provided written, informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center and carried out in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and applicable local laws and regulatory requirements.

Study assessments

Safety was evaluated throughout the study by the assessment of adverse events (AEs; NCI CTCAE version 3.0), laboratory abnormalities, physical examinations, performance status, vital signs, and electrocardiogram (ECG) profiles. AEs considered by the investigator to be related to either study drug were evaluated to determine the safety of this combination. In patients with measurable disease, objective response was determined according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v.1.0) [30].

Pharmacokinetic assessments

Blood samples for pharmacokinetic (PK) assessment were collected in K2EDTA tubes and sent to Bioanalytical Systems Inc (West Lafayette, IN, USA) for analysis. The plasma PK samples were analyzed using Pfizer-proprietary validated, sensitive, and specific high-performance liquid chromatographic tandem mass spectrometric (HPLC–MS/MS) methods, in compliance with Pfizer’s standard operating procedures.

The analytical method used for the determination of sunitinib and its metabolite showed precision of ≤6.1% (sunitinib) or ≤8.9% (metabolite), expressed as the between-day coefficients of variation (%CV) of the mean estimated concentrations of the quality control (QC) samples and accuracy ranging from −2.0 to 0.0% (sunitinib) or −5.0 to 1.4% (metabolite) expressed as the percent relative error (% RE) of the QC samples. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) of the assay was 0.100 ng/mL for both sunitinib and its metabolite, and the upper limit of quantitation (ULOQ) was 60.0 ng/mL for sunitinib and 20.0 ng/mL for the metabolite.

The analytical method used for the determination of pemetrexed showed precision of ≤13.3%, expressed as the between-day %CV of the mean estimated concentrations of the QC samples and accuracy ranging from 0.3 to 2.2% expressed as the % RE of the QC samples. The LLOQ of the pemetrexed assay was 0.100 μg/mL and the ULOQ was 100 μg/mL.

Full PK profiles were obtained from patients on the CDD schedule for sunitinib, its active metabolite SU12662, sunitinib + SU12662, and pemetrexed. Pemetrexed PK samples were collected on cycle 1 day 1 (i.e., in the absence of sunitinib) and cycle 2 day 1; predose, and 10 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 24 h post-pemetrexed dosing. Sunitinib PK samples were collected on cycle 1 day 15 (i.e., steady state levels of sunitinib in the absence of pemetrexed) and on cycle 2 day 1 predosing with pemetrexed or sunitinib, and then 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 24 h post-sunitinib dosing. Only patients that received at least 10 consecutive doses of sunitinib prior to sample collection on cycle 1 day 15 and cycle 2 day 1 were included in the summary to ensure that steady state had been achieved. PK analyses were performed on both the original dose-escalation cohorts and on the expanded NSCLC cohort. On Schedule 2/1, samples were collected only on day 1 of cycle 2.

Statistical methods

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, no confirmatory inferential statistical analyses were planned. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all patient characteristics, treatment administration/compliance, safety, PK parameters, and antitumor activity. Standard plasma PK parameters were estimated using non-compartmental methods.

Results

Patient characteristics

Twenty patients were enrolled on the CDD schedule, and seven patients were enrolled on the Schedule 2/1 dose-escalation cohorts. The patients were men and women with various types of malignancies and good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1), as detailed in Table 1. The Schedule 2/1 cohort included one patient who replaced a patient taken off study for disease progression. Two additional patients were included on the CDD schedule (one in the sunitinib 37.5 mg + pemetrexed 400 mg/m2 cohort and one in the sunitinib 37.5 mg + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 cohort, due to simultaneous enrollment of patients for the last slot in the respective cohorts (Table 1). An additional 15 patients with NSCLC were subsequently enrolled into the NSCLC expansion cohort on the CDD schedule (see below). This is a disease setting where single-agent sunitinib activity was previously observed [29]. In total, these 42 patients received 222 cycles of sunitinib therapy and 211 cycles of pemetrexed therapy (Table 2).

Safety

The MTD on the CDD schedule was determined to be sunitinib 37.5 mg/day with pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 q3w. On Schedule 2/1, at the next highest dose level (sunitinib 50 mg with pemetrexed 500 mg/m2; n = 7), only one DLT was observed. All DLTs are described in Table 3. As 37.5 mg was perceived to be a potentially efficacious dose and because prolonged target coverage was theoretically preferred over intermittent target coverage, the CDD MTD was taken forward as the proposed RP2D into the NSCLC expansion cohort.

In total, 12 (55%) patients treated on the CDD schedule MTD had at least one sunitinib dose delay, and the same number of patients had a pemetrexed dose delay. Three (14%) patients had dose delays of both sunitinib and pemetrexed between 3 and 4 weeks, 12 (55%) patients in this cohort had a sunitinib dose reduction to 25 mg, and 6 (27%) had a pemetrexed dose reduction to 400 mg/m2. Three patients discontinued sunitinib at the MTD due to AEs (abdominal pain, seizure, and thrombocytopenia); only the thrombocytopenia was considered sunitinib-related. The median number of cycles of sunitinib and pemetrexed received was 4 (range: 2–13) in the original CDD schedule MTD cohort (n = 7) and 5 (range: 1–8) in the NSCLC expansion cohort (n = 15). Across all patients treated at the CDD schedule MTD, 11 (50%) patients started at least 5 cycles of sunitinib. Sunitinib dose reductions occurred in 23 (56%) cycles on the original CDD schedule MTD cohort and 22 (28%) cycles on the NSCLC expansion cohort; 7 (47%) patients in the expansion cohort had at least one sunitinib dose reduction to 25 mg. Pemetrexed dose reduction occurred in 13 (32%) cycles on the original CDD schedule MTD and 6 (8%) cycles in the NSCLC expansion cohort; 3 (20%) patients in the expansion cohort had at least one pemetrexed dose reduction to 400 mg/m2. The median relative dose intensity (% actual/intended dose intensity) in the NSCLC expansion cohort across all cycles was 73% for sunitinib and 94% for pemetrexed. By cycle 5, 8/15 patients in the NSCLC expansion cohort remained on study and the median dose intensity was 76% (range: 50–100%) for sunitinib and 100% (75–100%) for pemetrexed. By cycle 8, 6/15 of these patients remained on study and the median dose intensity was 81% (range, 52–100%) for sunitinib and 88% (65–100%) for pemetrexed.

Treatment-related AEs at the MTDs on both schedules and on the NSCLC expansion cohort are shown in Table 4; these events were predominantly mild to moderate in severity. The most common non-hematologic AEs related to either drug, observed in patients treated on the CDD schedule MTD, were fatigue/asthenia (n = 16; 73%), nausea (n = 14; 64%), and anorexia (n = 13; 59%). In patients on the NSCLC expansion cohort, fatigue/asthenia (n = 11, 73%), nausea (n = 10, 67%), and diarrhea and dysgeusia (both n = 9, 60%) were most common. Serious AEs considered related to sunitinib treatment at the MTD included: febrile neutropenia (DLT), pancreatitis, pain, gastroenteritis, and muscular weakness (one event of each in separate patients). Hematologic laboratory abnormalities on the CDD schedule at the MTD included grade 3/4 lymphopenia, n = 7; grade 3 neutropenia, n = 5; and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, n = 4. Grade 2/3 anemia requiring blood transfusion occurred in nine patients.

The only DLT on Schedule 2/1 was febrile neutropenia (n = 1) at the highest dose level (sunitinib 50 mg + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, the Schedule 2/1 MTD). The median number of cycles of sunitinib and pemetrexed received per patient was 4 (range: 1–8) and dose reductions occurred in 6 (22%) and 3 (11%) cycles for sunitinib and pemetrexed, respectively (Table 2). Two patients on Schedule 2/1 had at least one sunitinib dose delay of 1–2 weeks, and two patients had a sunitinib dose reduction to 37.5 mg. Most treatment-related non-hematologic AEs were grade 1 or 2, with fatigue being the most common (n = 6). Serious AEs considered related to sunitinib treatment included febrile neutropenia (DLT), tumor perforation, and pyrexia (all n = 1). Hematologic laboratory abnormalities included grade 3/4 neutropenia (n = 2), grade 3 lymphopenia (n = 3), grade 3 thrombocytopenia (n = 1), and grade 2/3 anemia requiring blood transfusion (n = 2).

Across all cohorts, there were 5 deaths (1 at each dose level of the CDD schedule and 1 on Schedule 2/1). Most deaths were not considered related to the study drug; however, in a patient with metastatic bladder cancer on the CDD schedule treated with sunitinib 50 mg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 (above the MTD) who died of cerebral hemorrhage (day 14 cycle 1), a relationship to sunitinib exposure could not be ruled out. Prior to study entry, the patient had risk factors for a cerebral vascular accident, including a long-standing history of hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and hypertension. One patient died at the MTD on the CDD schedule secondary to respiratory distress during the third treatment cycle, and one patient died on the Schedule 2/1 MTD from hepatic failure during cycle 5 (both caused by disease progression). Disease progression was also recorded as the cause of death for one patient on the CDD schedule treated with sunitinib 37.5 mg and pemetrexed 400 mg/m2 during cycle 4. Cardiac arrest during cycle 4 was the cause of death of one patient on the CDD schedule (sunitinib 37.5 mg and pemetrexed 300 mg/m2); this was considered to result from pericardial effusion due to mesothelioma and was not considered related to the study drug.

Pharmacokinetics

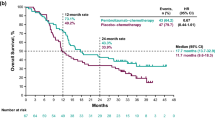

PK data revealed no clinically significant drug–drug interactions with co-administration of sunitinib (sunitinib, its active metabolite SU12662, and sunitinib + SU12662) and pemetrexed (all dose levels). On the CDD schedule at the MTD, the geometric mean ratios (sunitinib + pemetrexed relative to sunitinib alone) of the PK parameters related to maximum (C max) and total (AUC24) plasma exposure were 1.00 and 0.98 for sunitinib, respectively. Similarly, the geometric mean ratios were 1.07 and 1.04 for sunitinib + SU12662, respectively. These data suggest that the PK of sunitinib when co-administered with pemetrexed were equivalent to when it was administered alone. On Schedule 2/1, sunitinib, SU12662, and sunitinib + SU12662 PK parameters for day 1 of cycle 2 were not compared to those for day 15 of cycle 1, as the latter data corresponded to steady state levels; conversely, the data collected on day 1 of cycle 2 corresponded to the first day of dosing after the week off treatment. Due to the small number of PK evaluable patients on Schedule 2/1 (n = 4), the PK data on day 1 of cycle 2 when sunitinib was co-administered with pemetrexed could not be compared to historical control data of sunitinib alone. On the CDD schedule, at the MTD, the geometric mean ratios (sunitinib + pemetrexed relative to pemetrexed alone) of pemetrexed C max and AUC∞ were 1.07 and 0.94, respectively. On Schedule 2/1, the respective geometric mean ratios (sunitinib + pemetrexed relative to pemetrexed alone) of pemetrexed C max and AUC∞ were 1.19 and 0.93. Therefore, based on these data, co-administration of sunitinib did not appear to affect the PK of pemetrexed.

Furthermore, a comparison of the dose-corrected PK parameters at the MTD on the CDD schedule for sunitinib, SU12662, sunitinib + SU12662, and pemetrexed suggested similar PK profiles in patients with NSCLC and patients with other types of solid tumors. Dose-corrected PK parameters at the MTD were calculated using the PK parameters derived from the concentration–time profiles of all dose levels administered with paired PK observations. PK data at the MTD on both schedules are shown in Table 5 and Fig. 1.

Antitumor activity

Of 32 evaluable patients treated with sunitinib + pemetrexed on the CDD schedule, the best confirmed objective response was partial response (PR) in six (19%) patients and stable disease (SD) ≥8 weeks in 11 (34%) patients, for an overall ORR of 19%. The two patients with PRs on the original CDD schedule cohorts had primary diagnoses of bile duct cancer (treated in the sunitinib 37.5 mg + pemetrexed 300 mg/m2 cohort) and NSCLC classified as adenocarcinoma (sunitinib 50 mg + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2). Four patients on the CDD NSCLC expansion cohort, with histologies of adenocarcinoma (n = 2) and large cell carcinoma (n = 2), also had PRs. All had received prior doublet chemotherapy, and two responses were observed in patients with adenocarcinoma who had received prior bevacizumab and erlotinib, respectively. Of seven evaluable patients treated with sunitinib on Schedule 2/1, the best confirmed objective response was SD ≥8 weeks in two (28.6%) patients (maintained for 12–20 weeks) with primary diagnoses of NSCLC (adenocarcinoma) and anal cancer (squamous cell carcinoma).

Of the 21 patients with NSCLC treated in the dose-escalation and CDD expansion cohorts, five (24%) had PRs, seven (33%) had SD, and five (24%) had progressive disease (Table 6). The ORR among the 18 patients with NSCLC treated at the MTD on the CDD schedule was 24%. Sunitinib (25–50 mg/day) was administered to eight patients with NSCLC who were enrolled on a continuation study upon completion of 8 cycles of sunitinib/pemetrexed or at the discretion of the investigator. Best overall responses in these continuation patients (taking into account time spent on both the original and continuation protocols) included four patients who maintained PRs for a median of 11.5 months (range: 8.1–14.6 months), with a median PFS of 14.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.6–NA, n = 4). Additionally, SD for >12 months was achieved in two patients (13.6 and 12.8 months).

Discussion

The primary objective of this phase I dose-escalation study was to assess the MTD, safety, and tolerability of sunitinib, administered on the CDD schedule or Schedule 2/1, in combination with pemetrexed in patients with advanced solid malignancies refractory to standard therapy or for which standard therapy was not available. In anticipation that this combination could potentially be used in patients with advanced NSCLC or mesothelioma, the MTD cohort was expanded to further define the safety and antitumor activity for the RP2D.

The MTD on the CDD schedule was sunitinib 37.5 mg/day + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 q3w. On Schedule 2/1, the MTD was sunitinib 50 mg/day + pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 q3w, and this dose level was the maximum tested on this schedule. The overall safety profile at or below the MTD was generally tolerable and clinically manageable on both sunitinib treatment schedules, with most toxicities being mild or moderate (grade 1 or 2), and similar to those reported with either single-agent sunitinib or pemetrexed in advanced NSCLC [11, 22]. The individual immediate toxicity profiles of pemetrexed or sunitinib were not substantially adversely affected in combination. Pemetrexed could be administered at clinically efficacious doses for a median of 4.5 cycles in combination with sunitinib in the expanded NSCLC continuous daily dosing cohort. It is unclear whether there is a difference in the long-term tolerability of the CDD schedule and Schedule 2/1, as only two patients were administered sunitinib beyond cycle 5 at the sunitinib starting (MTD) dose on Schedule 2/1. Despite the initial tolerability of these doses in the first cycles of treatment (from which the DLTs and MTD were defined), many patients ultimately required dose reductions or dose delays. However, the chosen RP2D and schedule offered the potential for the highest possible systemic exposures over several cycles before individual tailoring of the regimen was required. In the expanded cohort at the MTD, the dose intensity of pemetrexed was well maintained at 500 mg/m2 without the need for any significant dose reductions; however, continuous daily dosing of sunitinib at 37.5 mg did require subsequent dose reductions to 25 mg after several cycles in half the patients, predominantly due to fatigue and anemia, suggestive of additive and cumulative toxicity. Nevertheless, despite the delays and dose reductions, the chosen RP2D offered long-term, sustained tolerability based on the stabilization of the dosing intensity after cycle 5 and potential efficacy in the patients treated. The starting dose of sunitinib at 37.5 mg has demonstrated clinically relevant antitumor activity and has been shown to achieve the target plasma concentrations (50–100 ng/mL) required to inhibit VEGFR and PDGFR phosphorylation, with the associated sustained inhibition of angiogenic targets [14, 15, 31]. It is possible that even lower doses of sunitinib may be sufficient to maintain clinical efficacy in some patients, since there were two patients with NSCLC on the MTD expansion cohort that maintained a tumor status of PR for an extended period (up to cycle 8) following a sunitinib dose reduction to 25 mg.

Antitumor activity was promising in this phase I clinical trial. The ORR among the 18 patients with NSCLC treated at the MTD on the CDD schedule was 23.5%, which is higher than the response rate reported for single-agent pemetrexed (9% ORR [12]) or sunitinib (ORR 11.1% on Schedule 4/2 and 2.1% on schedule CDD [22, 29]) in similar NSCLC patient populations. After entering the continuation study, four patients with NSCLC (with histologies of adenocarcinoma, n = 3 and large cell carcinoma, n = 1) achieved extended PRs (durations of 8.1–14.6 months) and two other patients maintained SD for >12 months (13.6 and 12.8 months, respectively). Median PFS in NSCLC patients in the continuation cohort was 14.6 months (95% CI 2.6–NA, n = 4).

Although antiangiogenic agents were demonstrated to be clinically active, their optimal scheduling and dosing alone and in combination with chemotherapy were not known at the time of study conduct. Preclinical studies suggest that angiogenesis inhibitors are most effective when administered at a dose and schedule that maintains a constant therapeutic concentration of the inhibitor in the circulation, whereas cytotoxic drugs should be administered at their MTDs followed by off-therapy intervals to recover from toxicity [32, 33]. Both the low dose continuous (37.5 mg CDD) and higher dose discontinuous dosing schedules (50 mg Schedule 4/2) of sunitinib alone had demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in RCC and GIST [24–29]. Although both schedules of sunitinib at the MTD were well tolerated in this study, it was felt that a lower continuous daily dose of sunitinib with pemetrexed might be more tolerable and potentially have more clinical activity than higher intermittent dosing. Moreover, our PK analyses revealed no evidence of drug–drug interactions with co-administration of sunitinib and pemetrexed or any evidence of drug accumulation after sunitinib CDD. Additionally, the phase II clinical trial of sunitinib alone at 37.5 mg on a CDD schedule in advanced refractory NSCLC demonstrated tolerability and efficacy without evidence of drug accumulation [29]. All these factors led to the decision by the clinical investigators to establish the RP2D and to expand the sunitinib CDD schedule in NSCLC patients. The CDD approach is supported by a recent phase III trial demonstrating efficacy and tolerability of sunitinib in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [34], whereas new data in RCC patients demonstrate similar efficacy of the CDD and discontinuous dosing schedules, but a lower toxicity and an improved tolerability profile with discontinuous dosing [35]. Clearly, there are still unanswered questions regarding sunitinib scheduling, and a difference between dosing schedules in toxicity might not be observed in every clinical setting [29].

At the time of study conduct, the optimal sequencing of antiangiogenic agents with chemotherapy had not been previously explored. Although antiangiogenic agents demonstrate additive or synergistic antitumor effects in combination with cytotoxic agents by transiently normalizing tumor vasculature, enhancing permeability, reducing interstitial pressure, facilitating chemotherapy diffusion, and reducing intratumoral hypoxia to enhance cytotoxic drug delivery to the tumor mass; concurrent therapy may also synergistically suppress bone marrow cellular production and increase toxicity, leading to decreased survival in preclinical models [36–38]. Recent data demonstrated that treatment with sunitinib in tumor-bearing mice for 5 days prior to chemotherapy resulted in a significantly greater improvement in animal survival when compared with concurrent therapy and that VEGF antagonists administered sequentially prior to chemotherapy protected against chemotherapy-induced systemic toxicity to improve survival [38]. As pemetrexed is not highly myelosuppressive and has a good tolerability profile [39], it is an ideal chemotherapy to combine with an antiangiogenic agent. However, despite the observed antitumor effects, toxicity was increased with concurrent administration and continuous dosing in our study. Although this single preclinical study suggests that treatment with an antiangiogenic agent prior to chemotherapy might be advantageous, it is unclear whether these effects translate clinically and whether there may be an optimal interval. Our study adds important information regarding the combination of antiangiogenic agents with chemotherapy in a setting where promising antitumor activity and clinical benefit were observed. In light of recent advancements, consideration of future exploration of sequencing and discontinuous regimens of sunitinib in combination with pemetrexed may further improve tolerability and optimize clinical responses.

In summary, it was possible to administer potentially efficacious doses of sunitinib on either a CDD schedule or on Schedule 2/1 with full doses of pemetrexed in this phase I study. Treatment was associated with an acceptable toxicity profile, with a slow cumulative need for dose modifications after multiple cycles. No clinically significant drug–drug interactions were observed. Sunitinib plus pemetrexed on a CDD schedule at the MTD was selected as the potential RP2D and was well tolerated. This dose/regimen demonstrated substantial clinical activity among NSCLC patients. In addition to determining the recommended dosing regimen for further exploration compared with pemetrexed monotherapy, these data also inform the starting doses for possible further exploration in combination with a platinum agent, given the increasing use of pemetrexed–platinum doublets in the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC.

References

Huber PE, Bischof M, Jenne J, Heiland S, Peschke P, Saffrich R, Gröne HJ, Debus J, Lipson KE, Abdollahi A (2005) Trimodal cancer treatment: beneficial effects of combined antiangiogenesis, radiation, and chemotherapy. Cancer Res 65:3643–3655

Christensen JG, Hall C, Hollister BA (2008) Antitumor efficacy of sunitinib malate in concurrent and sequential combinations with standard chemotherapeutic agents in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) nonclinical models. In: Proceedings of the 99th annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), 2008 (abstract)

Rosen L (2000) Antiangiogenic strategies and agents in clinical trials. Oncologist 5(Suppl 1):20–27

Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, Leighl N, Mezger J, Archer V, Moore N, Manegold C (2009) Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol 27:1227–1234

Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH (2006) Paclitaxel–carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 355:2542–2550

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2335–2342

Hanauske AR, Chen V, Paoletti P, Niyikiza C (2001) Pemetrexed disodium: a novel antifolate clinically active against multiple solid tumors. Oncologist 6:363–373

Mok TS, Ramalingam SS (2009) Maintenance therapy in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: a new treatment paradigm. Cancer 115:5143–5154

Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, Gatzemeier U, Digumarti R, Zukin M, Lee JS, Mellemgaard A, Park K, Patil S, Rolski J, Goksel T, de Marinis F, Simms L, Sugarman KP, Gandara D (2008) Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:3543–3551

Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, Denham C, Kaukel E, Ruffie P, Gatzemeier U, Boyer M, Emri S, Manegold C, Niyikiza C, Paoletti P (2003) Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 21:2636–2644

Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, Gatzemeier U, Tsao TC, Pless M, Muller T, Lim HL, Desch C, Szondy K, Gervais R, Shaharyar, Manegold C, Paul S, Paoletti P, Einhorn L, Bunn PA Jr (2004) Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 22:1589–1597

Russo F, Bearz A, Pampaloni G (2008) Pemetrexed single agent chemotherapy in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 8:216

Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, Kim JH, Krzakowski M, Laack E, Wu YL, Bover I, Begbie S, Tzekova V, Cucevic B, Pereira JR, Yang SH, Madhavan J, Sugarman KP, Peterson P, John WJ, Krejcy K, Belani CP (2009) Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet 374:1432–1440

Chow LQ, Eckhardt SG (2007) Sunitinib: from rational design to clinical efficacy. J Clin Oncol 25:884–896

Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, Louie SG, Christensen JG, Li G, Schreck RE, Abrams TJ, Ngai TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Carver J, Chan E, Moss KG, Haznedar JO, Sukbuntherng J, Blake RA, Sun L, Tang C, Miller T, Shirazian S, McMahon G, Cherrington JM (2003) In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res 9:327–337

Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Pryer NK, Cherrington JM (2003) SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2:471–478

O’Farrell AM, Abrams TJ, Yuen HA, Ngai TJ, Louie SG, Yee KW, Wong LM, Hong W, Lee LB, Town A, Smolich BD, Manning WC, Murray LJ, Heinrich MC, Cherrington JM (2003) SU11248 is a novel FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potent activity in vitro and in vivo. Blood 101:3597–3605

Murray LJ, Abrams TJ, Long KR, Ngai TJ, Olson LM, Hong W, Keast PK, Brassard JA, O’Farrell AM, Cherrington JM, Pryer NK (2003) SU11248 inhibits tumor growth and CSF-1R-dependent osteolysis in an experimental breast cancer bone metastasis model. Clin Exp Metastasis 20:757–766

Kim DW, Jo YS, Jung HS, Chung HK, Song JH, Park KC, Park SH, Hwang JH, Rha SY, Kweon GR, Lee SJ, Jo KW, Shong M (2006) An orally administered multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU11248, is a novel potent inhibitor of thyroid oncogenic RET/papillary thyroid cancer kinases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4070–4076

SUTENT PI (2008) SUTENT: summary of product characteristics. Pfizer Inc

Rosen LS, Bello CL, Mulay M, Dinolfo M, Baum C (2006) A phase I study evaluating administration of oral SU11248 (sunitinib malate) using a loading and maintenance dose on a 2/1 schedule in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 47:684 (abstract 2911)

Socinski MA, Novello S, Brahmer JR, Rosell R, Sanchez JM, Belani CP, Govindan R, Atkins JN, Gillenwater HH, Pallares C, Tye L, Selaru P, Chao RC, Scagliotti GV (2008) Multicenter, phase II trial of sunitinib in previously treated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:650–656

Kulke M, Lenz HJ, Meropol N, Posey J, Ryan DP, Picus J, Bergsland E, Stuart K, Tye L, Huang X, Li JZ, Baum CM, Fuchs CS (2008) Activity of sunitinib in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol 26:3403–3410

George S, Blay JY, Casali PG, Le Cesne A, Morgan JA, Pokela J, Quigley MT, Tassell V, Baum CM, Demetri GD (2007) Continuous daily dosing (CDD) of sunitinib malate (SU) compares favourably with intermittent dosing in pts with advanced GIST. J Clin Oncol 25(18S) (abstract 10015)

George S, Blay JY, Casali PG, Le Cesne A, Stephenson P, Deprimo SE, Harmon CS, Law CN, Morgan JA, Ray-Coquard I, Tassell V, Cohen DP, Demetri GD (2009) Clinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after imatinib failure. Eur J Cancer 45:1959–1968

Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, Curti BD, George DJ, Hudes GR, Redman BG, Margolin KA, Merchan JR, Wilding G, Ginsberg MS, Bacik J, Kim ST, Baum CM, Michaelson MD (2006) Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA 295:2516–2524

Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Rosenberg J, Bukowski RM, Curti BD, George DJ, Hudes GR, Redman BG, Margolin KA, Wilding G (2007) Sunitinib efficacy against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 178:1883–1887

Escudier B, Roigas J, Gillessen S, Harmenberg U, Srinivas S, Mulder SF, Fountzilas G, Peschel C, Flodgren P, Maneval EC, Chen I, Vogelzang NJ (2009) Phase II study of sunitinib administered in a continuous once-daily dosing regimen in patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27:4068–4075

Novello S, Scagliotti GV, Rosell R, Socinski MA, Brahmer J, Atkins J, Pallares C, Burgess R, Tye L, Selaru P, Wang E, Chao R, Govindan R (2009) Phase II study of continuous daily sunitinib dosing in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 101:1543–1548

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216

Faivre S, Delbaldo C, Vera K, Robert C, Lozahic S, Lassau N, Bello C, Deprimo S, Brega N, Massimini G, Armand JP, Scigalla P, Raymond E (2006) Safety, pharmacokinetic, and antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel oral multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:25–35

Miller KD, Sweeney CJ, Sledge GW Jr (2001) Redefining the target: chemotherapeutics as antiangiogenics. J Clin Oncol 19:1195–1206

Pietras K, Hanahan D (2005) A multitargeted, metronomic, and maximum-tolerated dose “chemo-switch” regimen is antiangiogenic, producing objective responses and survival benefit in a mouse model of cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:939–952

Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul J-L, Bang Y-J, Borbath I, Lombard-Bohas C, Valle J, Metrakos P, Smith D, Vinik A, Chen JS, Hörsch D, Hammel P, Wiedenmann B, Van Cutsem E, Patyna S, Lu DR, Blanckmeister C, Chao R, Ruszniewski P (2011) Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 364:501–513

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Olsen MR, Hudes GR, Burke JM, Edenfield WJ, Wilding G, Martell B, Hariharan S, Figlin RA (2011) Randomized phase II multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of sunitinib on the 4/2 versus continuous daily dosing schedule as first-line therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Renal EFFECT Trial. J Clin Oncol 29(Suppl 7) (abstract LBA308). Proceedings of the 2011 American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting

Jain RK (2005) Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science 307:58–62

Kerbel RS (2006) Antiangiogenic therapy: a universal chemosensitization strategy for cancer? Science 312:1171–1175

Zhang D, Hedlund EM, Lim S, Chen F, Zhang Y, Sun B, Cao Y (2011) Antiangiogenic agents significantly improve survival in tumor-bearing mice by increasing tolerance to chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:4117–4122

Kulkarni PM, Chen R, Anand T, Monberg MJ, Obasaju CK (2008) Efficacy and safety of pemetrexed in elderly cancer patients: results of an integrated analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 67:64–70

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participating patients and their families, as well as the global network of investigators, research nurses, study coordinators, and operations staff. We would also like to acknowledge Tanya Boutros for her work in coordinating the acquisition of PK data as well as contributing to the methods section. Medical writing support was provided by Lisa Cheyne at ACUMED® (Tytherington, UK) and was funded by Pfizer Inc. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Conflict of interest

L. Q. M. Chow, D. Jonker, S. A. Laurie, S. G. Diab, M. McWilliam, D. R. Camidge have no conflicts of interest to declare. C. Canil received an educational travel grant, honoraria for an advisory board, and speaker fees from Pfizer Inc. N. Blais received a research grant from Pfizer Inc. R. C. Chao, K. Zhang, A. Ruiz-Garcia, A. Thall, and L. Tye are employees of Pfizer Inc. and hold stock in Pfizer Inc., the manufacturers of SUTENT®.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chow, L.Q.M., Blais, N., Jonker, D.J. et al. A phase I dose-escalation and pharmacokinetic study of sunitinib in combination with pemetrexed in patients with advanced solid malignancies, with an expanded cohort in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 69, 709–722 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-011-1755-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-011-1755-0