Abstract

Objective

Physical exercise is associated with many health benefits. Especially for older adults it is challenging to achieve an appropriate adherence to exercise programs. The outcome expectations for exercise scale 2 (OEE-2) is a 13-item self-report questionnaire to assess negative and positive exercise outcome expectations in older adults. The aim of this study was to translate the OEE‑2 into German and to assess the psychometric properties of this version.

Methods

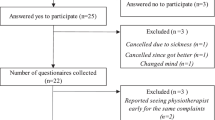

The OEE‑2 was translated from English into German including a forward and backward translation process. Psychometric properties were assessed in 115 patients with hip/pelvic fractures (76% female, mean age 82.5 years) and fear of falling during geriatric inpatient rehabilitation.

Results

Principal component analyses could confirm a two-factor solution (positive/negative OEE) that explained 58% of the total variance, with an overall internal reliability of α = 0.89. Cronbach’s α for the 9‑item positive OEE subscale was 0.89, for the 4‑item negative OEE subscale 0.79. The two subscales were correlated with rs = 0.49. Correlations of the OEE total score were highest with the perceived ability to manage falls, prefracture leisure time activities and prior training history (rs = 0.35–0.41).

Conclusion

These results revealed good internal reliability and construct validity of the German version of the OEE‑2. The instrument is valid for measuring physical exercise outcome expectations in older, German-speaking patients with hip or pelvic fractures and fear of falling.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Körperliches Training hat viele gesundheitliche Vorteile. Besonders älteren Menschen fällt es schwer, eine ausreichende Adhärenz bei Trainingsprogrammen zu erreichen. Ein Fragebogen mit 13 Fragen zur Beurteilung der negativen und positiven Erwartungen älterer Menschen hinsichtlich der Effekte eines körperlichen Trainings ist die „Outcome Expectations of Exercise Scale-2“ (OEE-2). Ziel der Studie war die Übersetzung des OEE‑2 und die Beurteilung der Testgütekriterien der deutschen Version.

Methodik

Die Originalversion des OEE‑2 wurde in einem Vorwärts- und Rückwärtsprozess vom Englischen ins Deutsche übersetzt. Die Testgütekriterien des Fragebogens wurden bei 115 Patienten nach Hüft- oder Beckenfraktur mit Sturzangst (76 % weiblich, Durchschnittsalter 82,5 Jahre) während einer stationären Rehabilitation untersucht.

Ergebnisse

Eine Hauptkomponentenanalyse bestätigte das Zwei-Faktoren-Modell (positiver/negativer erwarteter Nutzen) des Fragebogens, das 58 % der Varianz der Ergebnisse erklärte. Dabei war die interne Konsistenz t insgesamt α = 0,89. Cronbach’s α für die 9 Fragen der Subskala mit positivem erwartetem Nutzen war 0,89 bzw. 0,79 für die 4 Fragen der Subskala mit negativem erwartetem Nutzen. Beide Subskalen korrelierten mit rs = 0,49. Der Fragebogen zum positiven erwarteten Nutzen korrelierte am meisten mit der Selbstwirksamkeit zur Vermeidung von Stürzen, der körperlichen Aktivität vor der Fraktur und früheren Trainingsaktivitäten (rs = 0,35–0,41).

Schlussfolgerung

Die Ergebnisse zeigen eine gute interne Konsistenz und Konstruktvalidität der deutschen Version der OEE‑2 bei Patienten nach Hüft- oder Beckenfraktur mit Sturzangst. Das Instrument ist valide, um bei älteren, deutschsprachigen Menschen mit Hüft- oder Beckenfraktur und Sturzangst die Handlungsergebniserwartungen hinsichtlich eines körperlichen Trainings zu erheben.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

de Labra C, Guimaraes-Pinheiro C, Maseda A, Lorenzo T, Millán-Calenti JC (2015) Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr 15:154

Nicola F, Catherine S (2011) Dose-response relationship of resistance training in older adults: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 45(3):233–234

Chou C‑H, Hwang C‑L, Wu Y‑T (2012) Effect of exercise on physical function, daily living activities, and quality of life in the frail older adults: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93(2):237–244

Howe TE, Rochester L, Neil F, Skelton DA, Ballinger C (2011) Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD4963

Bean JF, Vora A, Frontera WR (2004) Benefits of exercise for community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85(7 Suppl 3):S31–42 (quiz S43–44)

Pedersen BK, Saltin B (2006) Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scand J Med Sci Sports 16(S1):3–63

Nascimento CM, Ingles M, Salvador-Pascual A, Cominetti MR, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Viña J (2019) Sarcopenia, frailty and their prevention by exercise. Free Radic Biol Med 132:42–49

Puts MTE, Toubasi S, Andrew MK, Ashe MC, Ploeg J, Atkinson E et al (2017) Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing 46(3):383–392

Viña J, Salvador-Pascual A, Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Gomez-Cabrera MC (2016) Exercise training as a drug to treat age associated frailty. Free Radic Biol Med 98:159–164

Chase J‑AD, Phillips LJ, Brown M (2017) Physical activity intervention effects on physical function among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act 25(1):149–170

de Vries NM, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JSM, Olde Rikkert MGM, Staal JB, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG (2012) Effects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 11(1):136–149

Diong J, Allen N, Sherrington C (2016) Structured exercise improves mobility after hip fracture: a meta-analysis with meta-regression. Br J Sports Med 50(6):346–355

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM et al (2012) Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD7146

Hopewell S, Adedire O, Copsey BJ, Boniface GJ, Sherrington C, Clemson L et al (2018) Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD12221

Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, Paul SS, Tiedemann A, Whitney J et al (2017) Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 51(24):1750–1758

Galloza J, Castillo B, Micheo W (2017) Benefits of exercise in the older population. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 28(4):659–669

WHO (2011) Global recommendations on physical activity for health. WHO, Genf

Kohler A, Kressig RW, Schindler C, Granacher U (2012) Adherence rate in intervention programs for the promotion of physical activity in older adults: a systematic literature review. Praxis 101(24):1535–1547

Picorelli AMA, Pereira LSM, Pereira DS, Felício D, Sherrington C (2014) Adherence to exercise programs for older people is influenced by program characteristics and personal factors: a systematic review. J Physiother 60(3):151–156

Sun F, Norman IJ, While AE (2013) Physical activity in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 13:449

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215

Bandura A (1997) The anatomy of stages of change. Am J Health Promot 12(1):8–10

Williams DM, Anderson ES, Winett RA (2005) A review of the outcome expectancy construct in physical activity research. Ann Behav Med 29(1):70–79

Bandura A (2004) Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 31(2):143–164

Resnick B, Nigg C (2003) Testing a theoretical model of exercise behavior for older adults. Nurs Res 52(2):80–88

Resnick B (2005) Reliability and validity of the outcome expectations for exercise scale‑2. J Aging Phys Act 13(4):382–394

Resnick B, Zimmerman SI, Orwig D, Furstenberg AL, Magaziner J (2000) Outcome expectations for exercise scale: utility and psychometrics. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 55(6):S352–356

Kampe K, Kohler M, Albrecht D, Becker C, Hautzinger M, Lindemann U et al (2017) Hip and pelvic fracture patients with fear of falling: development and description of the “step by step” treatment protocol. Clin Rehabil 31(5):571–581

Hetherington R (1954) The Snellen chart as a test of visual acuity. Psychol Forsch 24(4):349–357

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H (1983) Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 140(6):734–739

Hair JF Jr, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2014) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Pearson Education Limited, Essex

Brislin RW (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol 1(3):185–216

Gill DP, Jones GR, Zou GY, Speechley M (2008) The phone-FITT: a brief physical activity interview for older adults. J Aging Phys Act 16(3):292–315

Dias N, Kempen GIJM, Todd CJ, Beyer N, Freiberger E, Piot-Ziegler C et al (2006) Die Deutsche Version der Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I) [The German version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I). Z Gerontol Geriatr 39(4):297–300

Kempen GIJM, Yardley L, van Haastregt JCM, Zijlstra GAR, Beyer N, Hauer K et al (2008) The short FES-I: a shortened version of the falls efficacy scale-international to assess fear of falling. Age Ageing 37(1):45–50

Delbaere K, Close JCT, Mikolaizak AS, Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Lord SR (2010) The falls efficacy scale international (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age Ageing 39(2):210–216

Lawrence RH, Tennstedt SL, Kasten LE, Shih J, Howland J, Jette AM (1998) Intensity and correlates of fear of falling and hurting oneself in the next year: baseline findings from a Roybal center fear of falling intervention. J Aging Health 10(3):267–286

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Herrmann-Lingen C, Buss U, Snaith RP (2005) HADS‑D. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Deutsche Version. Ein Frageborgen zur Erfassung von Angst und Depressivität in der somatischen Medizin. Testdokumentation und Handanweisung, 2nd edn. Huber, Bern

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Taylor & Francis Inc, Hillsdale, N.J, p 400

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297–334

Nunnally JC (1978) Psychometric theory, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, p 730

Streiner DL (2003) Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess 80(1):99–103

Field A (2013) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics, 4th edn. SAGE, London, p 915

McHorney CA, Tarlov AR (1995) Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 4(4):293–307

Lawshe CH (1975) A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology 28:564–575

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Barbara Resnick for permission to translate the 13-item OEE‑2 and for providing expert advice related to the questionnaire.

Funding

The study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research [PROFinD, grant number 01EC1007A].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C. Becker has received consultant fees from E. Lilly company and Bosch Health care. He has also received speaker honoraria from Amgen and Nutricia. M. Gross, U. Lindemann, K. Kampe, A. Dautel, M. Kohler, D. Albrecht, G. Büchele, M. Hautzinger and K. Pfeiffer declare that they have no competing interests.

This study has been approved by the ethical review committees of the Faculties of Medicine in Tübingen (project number: 113/2011BO2). In accordance with the ethical standards and the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants (or legal guardian). The trial was registered under www.isrctn.org (ISRCTN79191813). All data are available on personal request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Data availability

All data are available on personal request from the corresponding author.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gross, M., Lindemann, U., Kampe, K. et al. German version of the outcome expectations for exercise scale-2. Z Gerontol Geriat 54, 582–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-020-01753-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-020-01753-y

Keywords

- Older adults

- Exercise training

- Positive exercise outcome expectation

- Negative exercise outcome expectation

- Psychometric properties