Abstract

Purpose

A growing body of evidence shows that consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPF) is associated with a higher risk of cardiometabolic diseases, which, in turn, have been linked to depression. This suggests that UPF might also be associated with depression, which is among the global leading causes of disability and disease. We prospectively evaluated the relationship between UPF consumption and the risk of depression in a Mediterranean cohort.

Methods

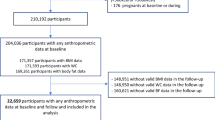

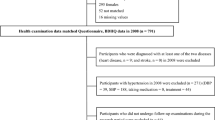

We included 14,907 Spanish university graduates [mean (SD) age: 36.7 year (11.7)] initially free of depression who were followed up for a median of 10.3 years. Consumption of UPF (industrial formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives, with little, if any, intact food), as defined by the NOVA food classification system, was assessed at baseline through a validated semi-quantitative 136-item food-frequency questionnaire. Participants were classified as incident cases of depression if they reported a medical diagnosis of depression or the habitual use of antidepressant medication in at least one of the follow-up assessments conducted after the first 2 years of follow-up. Cox regression models were used to assess the relationship between UPF consumption and depression incidence.

Results

A total of 774 incident cases of depression were identified during follow-up. Participants in the highest quartile of UPF consumption had a higher risk of developing depression [HR (95% CI) 1.33 (1.07–1.64); p trend = 0.004] than those in the lowest quartile after adjusting for potential confounders.

Conclusions

In a prospective cohort of Spanish university graduates, we found a positive association between UPF consumption and the risk of depression that was strongest among participants with low levels of physical activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- FFQ:

-

Food-frequency questionnaire

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MDS:

-

Mediterranean diet score

- MET:

-

Metabolic Equivalent Task

- Q:

-

Quartiles

- SCID:

-

Structured clinical interview

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SUN:

-

Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/follow-up University of Navarra

- UPF:

-

Ultra-processed food

References

World Health Organization (2017) Depression and other common mental disorders.https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/. Accessed 20 October 2018

Pan A, Keum N, Okereke O, Sun Q, Kivimaki M, Rubin R et al (2012) Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care 35:1171–1180

Pan A, Sun Q, Czernichow S, Kivimaki M, Okereke O, Lucas M et al (2012) Bidirectional association between depression and obesity in middle-aged and older women. Int J Obes (Lond) 36:595–602

Milaneschi Y, Simmons W, van Rossum E, Penninx B (2018) Depression and obesity: evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0017-5[Epub ahead of print]

Pan A, Lucas M, Sun Q, van Dam R, Franco O, Manson J et al (2010) Bidirectional association between depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Arch Intern Med 170:1884–1891

Molero P, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Ruiz-Canela M, Lahortiga F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Perez-Cornago A et al (2017) Cardiovascular risk and incidence of depression in young and older adults: evidence from the SUN cohort study. World Psychiatry 16:111

Mozaffarian D (2016) Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity. Circulation 133:187–225

Jeffery RW, Linde JA, Simon GE et al (2009) Reported food choices in older women in relation to body mass index and depressive symptoms. Appetite 52:238–240

Mikolajczyk RT, El Ansari W, Maxwell AE (2009) Food consumption frequency and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among students in three European countries. Nutr J 8:31

Sanchez-Villegas A, Zazpe I, Santiago S, Perez-Cornago A, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Lahortiga-Ramos F (2018) Added sugars and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, dietary carbohydrate index and depression risk in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project. Br J Nutr 119:211–221

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB et al (2016) NOVA. The star shines bright. [Food classification. Public health]. World Nutrition 7:28–38

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB et al (2019) Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr 12:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980018003762[Epub ahead of print]

Monteiro C, Cannon G, Moubarac J, Levy R, Louzada M, Jaime P (2018) The UN decade of nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr 21:5–17

Moubarac J, Batal M, Louzada M, Martinez Steele E, Monteiro C (2017) Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite 108:512–520

Schnabel L, Buscail C, Sabate J, Bouchoucha M, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B et al (2018) Association between ultra-processed food consumption and functional gastrointestinal disorders: results from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0137-1[Epub ahead of print]

Mendonça R, Pimenta A, Gea A, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Lopes A et al (2016) Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 104:1433–1440

Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Méjean C et al (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ 360:k322

Mendonça R, Lopes A, Pimenta A, Gea A, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Bes-Rastrollo M (2017) Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a mediterranean cohort: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am J Hypertens 30:358–366

Tavares LF, Fonseca SC, Garcia Rosa ML, Yokoo EM (2012) Relationship between ultra-processed foods and metabolic syndrome in adolescents from a Brazilian family doctor program. Public Health Nutr 15:82–87

Carlos S, De La Fuente-Arrillaga C, Bes-Rastrollo M, Razquin C, Rico-Campà A, Martínez-González MA et al (2018) Mediterranean diet and health outcomes in the SUN Cohort. Nutrients 10:439

Willett WC (2013) Nutritional epidemiology, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Vedia Urgell C, Bonet Monne S, Forcada Vega C, Parellada Esquius N (2005) Study of the use of psychiatric drugs in primary care (“Estudio de utilización de psicofármacos en atención primaria”). Aten Primaria 36:239–247

Sanchez-Villegas A, Schlatter J, Ortuno F, Lahortiga F, Pla J, Benito S, Martinez-González MA (2008) Validity of a self-reported diagnosis of depression among participants in a cohort study using the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I). BMC Psychiatry 8:43

de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Ruiz ZV, Bes-Rastrollo M, Sampson L, Martinez-González MA (2010) Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr 13:1364–1372

Martin-Moreno JM, Boyle P, Gorgojo L, Maisonneuve P, Fernandez-Rodriguez JC, Salvini S, Willett WC (1993) Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol 22:512–519

Martínez-González MA, López-Fontana C, Varo JJ, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martinez JA (2005) Validation of the Spanish version of the physical activity questionnaire used in the Nurses’ health study and health professionals’ follow-up study. Public Health Nutr 8:920–927

Lahortiga-Ramos F, Unzueta CR, Zazpe I, Santiago S, Molero P, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA (2018) Self-perceived level of competitiveness, tension and dependency and depression risk in the SUN cohort. BMC Psychiatry 18:241

Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C (2015) Tablas de Composición de los Alimentos. Guía de Prácticas; Ed. Pirámide, Madrid

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C et al (2003) Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 348:2599–2608

Bes-Rastrollo M, Pérez VR, Sánchez-Villegas A, Alonso A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA (2005) Validation of the weight and body mass index self-declared by participants in a cohort of university graduates. Rev Esp Obes 3:352–358

Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA (2002) Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 155:176–184

Desquilbet L, Mariotti F (2010) Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med 29:1037–1057

Sánchez-Villegas A, Henríquez-Sánchez P, Ruiz-Canela M, Lahortiga F, Molero P, Toledo E et al (2015) A longitudinal analysis of diet quality scores and the risk of incident depression in the SUN Project. BMC Med 13:197

Sánchez-Villegas A, Pérez-Cornago A, Zazpe I, Santiago S, Lahortiga F, Martínez-González MA (2017) Micronutrient intake adequacy and depression risk in the SUN cohort study. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1514-z[Epub ahead of print]

Sánchez-Villegas A, Ruíz-Canela M, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Gea A, Shivappa N, Hébert J et al (2015) Dietary inflammatory index, cardiometabolic conditions and depression in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra cohort study. Br J Nutr 114:1471–1479

Sánchez-Villegas A, Toledo E, de Irala J, Ruiz-Canela M, Pla-Vidal J, Martínez-González MA (2012) Fast-food and commercial baked goods consumption and the risk of depression. Public Health Nutr 15:424–432

Sánchez-Villegas A, Verberne L, De Irala J, Ruíz-Canela M, Toledo E, Serra-Majem L et al (2011) Dietary fat intake and the risk of depression: the SUN Project. PLoS One 6:e16268

Canella D, Louzada M, Claro R, Costa J, Bandoni D, Levy R et al (2018) Consumption of vegetables and their relation with ultra-processed foods in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 52:50

Steele EM, Popkin BM, Swinburn B et al (2017) The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr 15:6

Vandevijvere S, De Ridder K, Fiolet T et al (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed food products and diet quality among children, adolescents and adults in Belgium. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1870-3

Kelly B, Jacoby E (2018) Public health nutrition special issue on ultra-processed foods. Public Health Nutr 21:1–4

Rienks J, Dobson A, Mishra G (2013) Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-aged women: results from a large community-based prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr 67:75–82

Skarupski K, Tangney C, Li H, Evans D, Morris M (2013) Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J Nutr Health Aging 17:441–445

Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Covas M et al (2013) Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression: the PREDIMED randomized trial. BMC Med 11:208

Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, Jacka F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Kivimaki M, Tasnime Akbaraly T (2018) Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8[Epub ahead of print]

Vreeburg S, Hoogendijk W, van Pelt J, DeRijk R, Verhagen J, van Dyck R et al (2009) Major Depressive Disorder and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Activity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:617–626

Zunszain PA, Hepgul N, Pariante CM (2013) Inflammation and depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 14:135–151

Webb M, Davies M, Ashra N, Bodicoat D, Brady E, Webb D et al (2017) The association between depressive symptoms and insulin resistance, inflammation and adiposity in men and women. PLoS One 12:e0187448

Foster J, McVey Neufeld K (2013) Gut–brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci 36:305–312

Small DM, DiFeliceantonio AG (2019) Processed foods and food reward. Science 363:346–347

Schuch F, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward P, Silva E et al (2018) Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry 175:631–648

Sánchez-Villegas A, Ara I, Guillén-Grima F, Bes-Rastrollo M, Varo-Cenarruzabeitia J, Martínez-González MA (2008) Physical activity, sedentary index, and mental disorders in the SUN cohort study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:827–834

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Design strategies to improve study accuracy. Modern epidemiology, 3rd edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 168–182

Acknowledgements

We thank very specially all participants in the SUN cohort for their long-standing and enthusiastic collaboration, and our advisors from Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health (Walter Willett, Alberto Ascherio and Frank B. Hu) who helped us to design the SUN Project. We are also grateful to the other members of the SUN Group for administrative, technical, and material support.

Funding

The SUN Project has received funding from the Spanish Government-Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (RD 06/0045, CIBER-OBN, Grants PI10/02658, PI10/02293, PI13/00615, PI14/01668, PI14/01798, PI14/01764, PI17/01795, and G03/140), the Navarra Regional Government (27/2011, 45/2011, 122/2014), and the University of Navarra. CGD was supported by a predoctoral contract for training in health research (PFIS) (FI18/00073) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The present study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol (including the informed consent process) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Navarra. The voluntary completion of the self-administered baseline questionnaire was considered to imply informed consent. All potential participants were informed of their right to refuse to participate in the study or to withdraw their consent to participate at any time. The SUN study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT02669602.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez-Donoso, C., Sánchez-Villegas, A., Martínez-González, M.A. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of depression in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN Project. Eur J Nutr 59, 1093–1103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01970-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01970-1