Abstract

Background

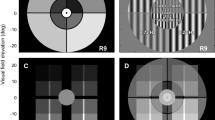

We develop the logic for a stimulus that can evaluate cone-dependent spatial summation and detail the modelling and interpretation of thresholds obtained with this stimulus.

Methods

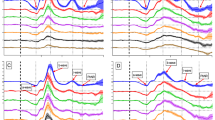

Fifteen observers participated, including two young normals tested extensively in control experiments, and a clinical trial based on four observers with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), four age-similar controls and five young observers. Monocular spatial summation functions were measured with contrast-modulated Gabor targets that approximated the optimal visual contrast detector. Thresholds were returned from a yes/no adaptive psychophysical algorithm. By fine titration along the size domain it was demonstrated that the spatial summation of normal observers can be adequately described by a two-component model. A reduced set of variables are proposed for clinical applications and the model was applied to data derived using these variables in persons with AMD and age-similar controls.

Results

We do not find a significant age-related loss of contrast sensitivity in our normal group. On the other hand, persons with early AMD exhibited a 0.41 log unit loss of sensitivity (P=0.04) from age-similar controls, without any change in their maximum summation area (Amax).

Conclusions

The nature of the spatial summation is consistent with the interpretation that early AMD produces a decrease in cone input to post-receptoral mechanisms in the absence of neural remodelling.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson AJ, Vingrys AJ (2001) The effect of object blur on luminance-pedestal flicker thresholds. In: Wall M, Mills RP (eds) Perimerty update 2000/2001. Kugler Publications, The Hague, pp 115–120

Barlow HB (1958) Temporal and spatial summation in human vision at different background luminances. J Physiol 141:337–350

Bird AC, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Chisholm IH, Coscas G, Davis MD, de Jong PT, Klaver CC, Klein BE, Klein R et al (1995) An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration: the international ARM epidemiological study group. Surv Ophthalmol 39:367–374

Bowen RW, Wilson HR (1994) A two-process analysis of pattern masking. Vision Res 34:645–657

Brown B, Peterken C, Bowman KJ, Crassini B (1989) Spatial summation in young and elderly observers. Ophthal Physiol Opt 9:310–313

Campbell FW, Green DG (1965) Optical and retinal factors affecting visual resolution. J Physiol 181:576–593

Chaparro A, Stromeyer CF III, Huang EP, Kronauer RE, Eskew RT Jr (1993) Colour is what the eye sees best. Nature 361:348–350

Curcio CA, Medeiros NE, Millican CL (1996) Photoreceptor loss in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37:1236–1249

Curcio CA, Owsley C, Jackson GR (2000) Spare the rods, save the cones in aging and age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41:2015–2018

Drum B (1984) Flicker and suprathreshold spatial summation: evidence for a two-channel model of achromatic brightness. Percept Psychophys 36:245–250

Eisner A, Klein ML, Zilis JD, Watkins MD (1992) Visual function and the subsequent development of exudative age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sc 33:3091–3102

Eisner A, Stoumbos VD, Klein ML, Fleming SA (1991) Relations between fundus appearance and function: eyes whose fellow eye has exudative age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 32:8–20

Elliott D, Whitaker D, MacVeigh D (1990) Neural contribution to spatiotemporal contrast sensitivity decline in healthy aging eyes. Vision Res 40:541–548

Eysel UT, Peichl L (1985) Regenerative capacity of retinal axons in the cat, rabbit, and guinea pig. Exp Neurol 88:757–766

Felius J, Swanson WH, Fellman RL, Lynn JR, Starita RJ (1997) Spatial summation for selected ganglion cell mosaics in patients with glaucoma. In: Wall M, Heijl A (eds) Perimety update 1996/1997. Kugler Publications, Amsterdam, pp 213–221

Fellman RL, Lynn JR, Starita RJ, Swanson WH (1989) Clinical importance of spatial summation in glaucoma. In: Heijl A (ed) Perimety update 1988/1989. Kugler and Ghedini, Amsterdam, pp 313–324

Gao H, Hollyfield JG (1992) Aging of the human retina. Differential loss of neurons and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 33:1–17

Gowdy PD, Stromeyer CF III, Kronauer RE (1999) Facilitation between the luminance and red-green detection mechanisms: enhancing contrast differences across edges. Vision Res 39:4098–4112

Haas A, Flammer J, Schneider U (1986) Influence of age on the visual fields of normal subjects. Am J Ophthalmol 101:199–203

Hess RF (1990) Rod-mediated vision: role of post-receptoral filters. In: Hess RF, Sharpe LT, Nordby K (eds) Night vision: basic, clinical and applied aspects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 3–48

Hess RF, Howell ER (1978) The influence of field size for a periodic stimulus in strabismic amblyopia. Vision Res 18:501–503

Johnson CA, Adams AJ, Lewis RA (1989) Evidence for a neural basis of age-related visual field loss in normal observers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 30:2056–2064

Kapadia MK, Westheimer G, Gilbert CD (1999) Dynamics of spatial summation in primary visual cortex of alert monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:12073–12078

Lantham K, Whitaker D, Wild JD (1994) Spatial summation of the light threshold as a function of visual field location and age. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 14:71–78

Mareschal I, Shapley RM (2004) Effects of contrast and size on orientation discrimination. Vision Res 44:57–67

Mayer MJ, Spiegler SJ, Ward B, Glucs A, Kim CB (1992) Mid-frequency loss of foveal flicker sensitivity in early stages of age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 33:3136–3142

Nameda N, Kawara T, Ohzu H (1989) Human visual spatio-temporal frequency performance as a function of age. Optom Vis Sci 66:760–765

O'Loughlin RK (2004) Visual and systemic correlates in AMD. Unpublished MOptom Dissertation, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Owsley C, Sekuler R (1982) Spatial summation, contrast threshold and aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 22:130–133

Owsley C, Sekuler R, Siemsen D (1983) Contrast sensitivity throughout adulthood. Vision Res 23:689–699

Pentland A (1980) Maximum likelihood estimation: the best-PEST. Percept Psychophys 28:377–379

Phipps JA, Dang T, Vingrys AJ, Guymer RH (2004) Flicker perimetry losses in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:3355–3360

Phipps JA, Guymer RH, Vingrys AJ (2003) Loss of cone function in age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44:2277–2283

Phipps JA, Zele AJ, Dang T, Vingrys AJ (2001) Fast psychophysical procedures for clinical testing. Clin Exp Optom 84:264–269

Polat U, Tyler CW (1999) What pattern the eye sees best. Vision Res 39:887–895

Regan D, Whitlock JA, Murray TJ, Beverly KI (1980) Orientation-specific losses of contrast sensitivity in multiple sclerosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 19:324–328

Sanyal S, Hawkins RK, Jansen HG, Zeilmaker GH (1992) Compensatory synaptic growth in the rod terminals as a sequel to partial photoreceptor cell loss in the retina of chimaeric mice. Development 114:797–803

Sceniak MP, Ringach DL, Hawken MJ, Shapley R (1999) Contrast's effect on spatial summation by macaque V1 neurons. Nature Neurosci 2:733–739

Sjostrand J, Frisen L (1977) Contrast sensitivity in macular disease. A preliminary report. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 55:507–514

Swanson WH, Felius J, Birch DG (2000) Effect of stimulus size on static visual fields in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 107:1950–1954

Swanson WH, Felius J, Pan F (2004) Perimetric defects and ganglion cell damage: interpreting linear relations using a two-stage neural model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:466–472

Taylor HR, West SK (1989) The clinical grading of lens opacities. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol 17:81–88

Watson AB, Barlow HB, Robson JG (1983) What does the eye see best? Nature 302:419–422

Watson AB, Pelli D (1983) QUEST: a Bayesian adaptive psychometric method. Percept Psychophys 33:113–120

Watson AB, Turano K (1995) The optimal motion stimulus. Vision Res 35:325–336

Westheimer G (1967) Spatial interaction in human cone vision. J Physiol 190:139–154

Wilson ME (1967) Spatial and temporal summation in impaired regions of the visual field. J Physiol 189:189–208

Wilson ME (1970) Invariant features of spatial summation with changing locus in the visual field. J Physiol 207:611–622

Zele AJ, Vingrys AJ (2000) Flicker adaptation can be explained by probability summation between independent ON- and OFF-processors. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 28:227–229

Zele AJ, Vingrys AJ (2005) Cathode-ray-tube monitor artefacts in neurophysiology. J Neurosci Meth 141:1–7

Zhang L, Sturr JF (1995) Aging, background luminance, and threshold-duration functions for detection of low spatial frequency sinusoidal gratings. Optom Vis Sci 72:198–204

Acknowledgements

Supported by an Australian Research Council Linkage Project (LP0211474) grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zele, A.J., O'Loughlin, R.K., Guymer, R.H. et al. Disclosing disease mechanisms with a spatio-temporal summation paradigm. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmo 244, 425–432 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-005-0121-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-005-0121-5