Abstract

Objective

The demographic change leads to a shrinking German work force. Depressive symptoms cause many days absent at work, loss of productivity and early retirement. Therefore, pathways for prevention of depressive symptoms are important for the maintenance of global competitiveness. We investigated the role of work-family conflict (WFC) in the well-known association between work stress and depressive symptoms.

Methods

A total of 6,339 employees subject to social insurance, born in 1959 or 1965 and randomly drawn from 222 sample points in Germany participated in the first wave of the leben in der Arbeit-study. In the analysis, 5,906 study subjects working in full-time or part-time positions were included. Work stress was measured by effort–reward imbalance ratio, depressive symptoms by the applied Becks depression inventory (BDI-V) and WFC by items of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ)-scale. Multiple linear regression analysis adjusted for age, education, negative affectivity (PANAS), overcommitment and number of children was performed. Mediation was defined according to the criteria of Baron and Kenny.

Results

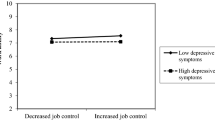

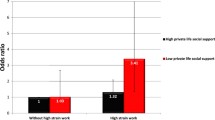

Work stress was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (BDI-V) in all full-time [ß1female = 6.61 (95 % CI 3.95–9.27); ß1male = 8.02 (95 % CI 5.94–10.09)] and female part-time employees [ß2female = 4.87 (95 % CI 2.16–7.59)]. When controlling for WFC effect, estimates became smaller in men and were even halved in women. WFC was also significantly associated with work stress and depressive symptoms: All criteria for partial mediation between work stress and depressiveness were fulfilled.

Conclusions

Prevention of WFC may help to reduce days absent at work and early retirement due to work stress-related depressive symptoms in middle-aged women and men.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allen TD, Herst DEL, Bruck CS, Sutton M (2000) Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol 5:278–308

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The mediator- moderator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Bond JT, Galinsky E, Swanberg JE (1998) The national study of the changing workforce 1997. In vol. 2. Families and Work Institute, New York

Börsch-Supan A, Wilke CB (2009) Zur mittel- und langfristigen Entwicklung der Erwerbstätigkeit in Deutschland. ZAF 42:29–48

Busch MA, Maske UE, Ryl L, Schlack R, Hapke U (2013) Prävalenz von depressiver Symptomatik und diagnostizierter depression bei erwachsenen in deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 56:733–739

Dong Y, Peng CYJ (2013) Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus 2:222

Dorner M, Heining J, Jacobebbinghaus P, Seth S (2010) The Sample of Integrated Labour Market Biographies. In: Schmollers Jahrbuch. Z Wirtsch Sozialwiss 130:599–608

Doshi JA, Cen L, Polsky D (2008) Depression and retirement in late middle-aged U.S. workers. Health Serv Res 43:693–713

Dragano N, Moebus S, Jöckel KH et al (2008) Two models of job stress and depressive symptoms. Results from a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:72–78

Emslie C, Hunt K, Macintyre S (1999) Problematizing gender, work, and health: the relationship between gender, occupational grade, working conditions, and minor morbidity in full-time bank employees. Soc Sci Med 48:33–48

Frone MR, Russell M, Barnes GM (1996) Work-family conflict, gender, and health-related outcomes: a study of employed parents in two community samples. J Occup Health Psychol 1:57–69

Frone MR, Yardley JK, Markel KS (1997) Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. J Vocat Behav 50:145–167

Fuß I, Nübling M, Hasselhorn HM, Schwappach D, Rieger MA (2008) Working conditions and work-family conflict in German hospital physicians: psychosocial and organisational predictors and consequences. BMC Public Health 8:353

Godin I, Kittel F, Coppieters Y et al (2005) A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Health 5:67

Grant-Vallone EJ, Donaldson SI (2001) Consequences of work-family conflict on employee well-being over time. Work Stress 15:214–226

Hasselhorn HM, Peter R, Rauch A, Schroeder H, Swart E, Bender S, du Prel JB, Ebener M, March S, Trappmann M, Steinwede J, Mueller BH (2014) Cohort profile: the lidA cohort study—a german cohort study on work, age, health and work participation. Int J Epidemiol. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu021

Jacobi F, Hoyer J, Wittchen HU (2004) Seelische Gesundheit in Ost und West: analysen auf der Grundlage des Bundesgesundheitssurveys. Z Klin Psychol Psychother 33:251–260

Jöckel KH, Babitsch B, Bellach BM et al (1998) Messung und Quantifizierung soziodemographischer Merkmale in epidemiologischen Studien. Empfehlungen, http://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Methodik/Empfehlungen/empfehlungen_node.html. Accessed 7 April 2014

Kato M, Yamazaki Y (2009) An examination of factors related to work-to-family conflict among employed men and women in Japan. J Occup Health. 51:303–313

Kelloway EK, Gottlieb BH, Barham L (1999) The source, nature, and direction of work and family conflict: a longitudinal investigation. J Occup Health Psychol 4:337–346

Kikuchi Y, Nakaya M, Ikeda M, Narita K, Takeda M, Nishi M (2010) Effort-reward imbalance and depressive state in nurses. Occup Med (Lond) 60:231–233

Kinunnen U, Geurts S, Mauno S (2004) Work-to-family conflict and its relationship with well-being: a one year longitudinal study. J Vocat Behav 18:1–23

Kirchmeyer C, Cohen A (1999) Different strategies for managing the work/non-work interface: a test for unique pathways to work outcomes. Work Stress 13:59–73

Koopmans PC, Roelen CAM, Groothoff JW (2008) Sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 81:711–719

Li XY, Guo YS, Lu WJ, Wang SJ, Chen K (2006) Association between social psychological factors and depressive symptoms among healthcare workers. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing ZaZhi 24:454–457

Peeters M, de Jonge J, Janssen PP, van der Linden S (2004) Work-Home Interference, Job Stressors, and Employee Health in a Longitudinal Perspective. Int J Stress Manag 11:305–322

Pejtersen JH, Kristensen TS, Borg V, Bjorner JB (2010) The second version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Scand J Public Health 38(3 suppl):8–24

Peter R, Hammarström A, Hallqvist J, Siegrist J, Theorell T (2006) Does occupational gender segregation influence the association of effort-reward imbalance with myocardial infarction in the SHEEP study? Int J Behav Med 13:34–43

Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Hoewyk JV, Solenberger P (2001) A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol 27: 85–95. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 12-001

Rau R, Gebele N, Morling K, Rösler U (2010). Untersuchung arbeitsbedingter Ursachen für das Auftreten von depressiven Störungen. Abschlussbericht zum Projekt “Untersuchung arbeitsbedingter Ursachen für das Auftreten von depressiven Störungen“-Projekt F 1865. ISBN 978-3-88261-1144

Sakata Y, Wada K, Tsutsumi A et al (2008) Effort-reward imbalance and depression in Japanese medical residents. J Occup Health 50:498–504

Schmitt M, Beckmann M, Dusi D, Maes J, Schiller A, Schonauer K (2003) Messgüte des vereinfachten beck-depressions-inventars (BDI-V). Diagnostica 49:147–156

Schmitt M, Altstötter-Gleich C, Hinz A, Maes J, Brähler E (2006) Normwerte für das vereinfachte beck-depressions-inventar (BDI-V) in der Allgemeinbevölkerung. Diagnostica 52:51–59

Schneider A, Hommel G, Blettner M (2010) Linear regression analysis: part 14 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int 107:776–782

Schröder H, Kersting A, Steinwede J (2013) Methodenbericht zur Haupterhebung lidA: leben in der Arbeit. FDZ-Methodenreport 1/2013, Nürnberg

Schulz M, Damkröger A, Voltmer E et al (2011) Work-related behaviour and experience pattern in nurses: impact on physical and mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 18:411–417

Siegrist J (1996) Adverse health effects of high-effort/low- reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1:27–41

Siegrist J, Peter R (2000) The effort-reward imbalance model. In: Schnall P, Belkic K, Landsbergis P, Baker D (eds) The workplace and cardiovascular disease. Occupational Medicine, State of the Art Reviews 15:83–87

Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T et al (2004) The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: european comparisons. Soc Sci Med 58:1483–1499

Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG (1999) Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med 56:302–307

Stocke V (2004) Entstehungsbedingungen von Antwortverzerrungen durch soziale Erwünschtheit ZfS 33:303–320

Thompson ER (2007) Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). J Cross Cult Psychol 38:227–242

TK-health report (2008) Arbeitsunfähigkeiten und Arzneiverordnungen. Schwerpunkt psychische Störungen. http://www.tk.de/centaurus/servlet/contentblob/48834/Datei/3592/Gesundheitsreport-7.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2013

Tsutsumi A, Kawanami S, Horie S (2012) Effort-reward imbalance and depression among private practice physicians. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85:153–161

TsutsumiA Kayaba K, Theorell T, Siegrist J (2001) Association between job stress and depression among Japanese employees threatened by job loss in a comparison between two complementary job-stress models. Scand J Work Environ Health 27:146–153

Van der Heijden BI, Demerouti E, Bakker AB, NEXT Study Group coordinated by Hans-Martin Hasselhorn (2008) Work-home interference among nurses: reciprocal relationships with job demands and health. J Adv Nurs 62:572–584

Van Hooff ML, Geurts SA, Taris TW, Kompier MA, Dikkers JS, Houtman IL, van den Heuvel FM (2005) Disentangling the causal relationships between work-home interference and employee health. Scand J Work Environ Health 31:15–29

Van Veldhoven MJPM, Beijer SE (2012) Workload, work-to-family conflict, and health: gender differences and the influence of private life context. J Soc Issues 68:665–683

Wang J, Patten SB, Currie S, Sareen J, Schmitz N (2012) A population-based longitudinal study on work environmental factors and the risk of major depressive disorder. Am J Epidemiol 176:52–59

Watai I, Nishikido N, Murashima S (2008) Gender difference in work-family conflict among Japanese information technology engineers with preschool children. J Occup Health 50:317–327

Acknowledgments

This research was financed in the frame of the lidA-study by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the Project Numbers 01 ER 0806, 01 ER 0825, 01 ER 0826, 01 ER 0827. We thank the Pearson Assessment and Information GmbH for permission for using the BDI-V-questionnaire. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

du Prel, JB., Peter, R. Work-family conflict as a mediator in the association between work stress and depressive symptoms: cross-sectional evidence from the German lidA-cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 88, 359–368 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0967-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0967-0