Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disruptive effect on people with haematological cancers, who represent a high-risk population due to the nature of their disease and immunosuppressive treatments. We aimed to identify the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on haematology patients and identify correlated factors to inform the development of appropriate supportive interventions.

Methods

Three hundred and ninety-four respondents volunteered their participation in response to a study advertisement distributed online through established haematology groups. Participants completed a self-report online survey exploring wellbeing, psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and fear of cancer recurrence.

Results

At least 1 in 3 respondents (35%) reported clinical levels of distress and nearly 1 in 3 (32%) identified at least one unmet need. Among respondents in remission (n = 134), clinical fear of cancer recurrence was reported by nearly all (95%). Unmet needs, pre-existing health conditions, younger age, financial concerns, and perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 were the dominant factors contributing to psychological distress during the pandemic. Psychological distress, lost income, perceived inadequate support from care team, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and being a woman were significantly associated with unmet needs. Psychological distress and concern about the impact of COVID-19 on cancer management were significantly associated with fear of cancer recurrence among respondents in remission.

Conclusion

Results highlight the high psychological burden and unmet needs experienced by people with haematological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic and indicate a need for innovative solutions to rapidly identify distress and unmet needs during, and beyond, pandemic times.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented many challenges for those with cancer, with members of this population subgroup at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 and experiencing severe complications or death from the virus [1]. Due to these vulnerabilities, powerful health messages have stressed the higher risk posed to cancer patients and many cancer treatments have been modified or delayed to minimise patients’ exposure to COVID-19 [2]. Although these changes to usual care were designed to protect vulnerable cancer patients in the short term, evidence is beginning to emerge of the potential long-term consequences of these actions. For example, fear of infection has resulted in many patients making their own choice to delay care, with a study conducted by the American College of Emergency Physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic finding that 29% of the cancer patients surveyed reported they had avoided visiting the emergency department due to fears of contracting the virus [3]. In Australia, the context of the present study, cancer hospitals reported a 40% decline in patient presentations for cancer management appointments during the pandemic [4], similar to reductions reported in other countries [5, 6]. These figures are concerning given recently published research indicates that delaying curative treatment by just 1 month increases cancer patients’ risk of death by as much as 10% [7]. These unintended consequences may not only lead to worse treatment outcomes, but also significant psychological morbidity.

Emerging research suggests that the disruptions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to heightened levels of psychological distress and fear of recurrence (FCR) among people with cancer [8,9,10]. Early studies suggest that concerns about the perceived impact of COVID-19 on cancer management and treatment delays contribute to increased distress and FCR in cancer patients [8, 11]. Having recent cancer treatment, pre-existing health conditions, having lower levels of formal education qualifications, female gender, and younger age have been found to correlate with distress [8, 9, 11]. Qualitative findings suggest that the challenges created by the pandemic, such as fears of contracting COVID-19, reduced access to support from healthcare providers and family, and financial hardship, may also exacerbate distress in cancer patient [8, 10,11,12]. However, these results have been mixed and apply primarily to patients with solid cancers.

There is limited research focused on the psychological effects of the pandemic on people with haematological cancers. This is concerning given those with a haematological cancer represent a particularly vulnerable subgroup of cancer patients due to (i) the nature of their disease (i.e., damage to the immune system) and (ii) immunosuppressive treatments such as haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), which places patients at increased risk of respiratory viral infections [13, 14]. Additionally, the pandemic has severely impacted the availability of donor stem cell products for haematological cancer patients who are planned to undergo HSCT. Finding a suitable stem cell donor is challenging and there may not be a suitable donor identified in the same country as the recipient. In Australia, over 80% of donated stem cells come from international volunteer donors [15]. Rapid border closures and flight changes have limited the availability of stem cell products, creating significant challenges for those who were planned to undergo potentially life-saving HSCT [16,17,18].

Since people with haematological cancers have a higher risk of infection and face significant treatment-related challenges, their supportive care needs may be higher than those seen in patients with solid cancers and haematological cancers in non-pandemic times. Examining these supportive care needs, assessing psychological wellbeing, and identifying which variables are related to psychosocial wellbeing is critical to developing interventions that are responsive to those with haematological cancers and mitigate the psychological consequences of the pandemic.

Therefore, the present study adopted an exploratory approach to investigate the prevalence of psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and FCR among haematological cancer patients during the pandemic and identify correlated factors, including socio-demographic, key clinical, and COVID-19-related factors. A second aim was to investigate whether socio-demographic characteristics moderate the relationships between these factors and psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and FCR to assist in identifying high-risk groups who may benefit most from interventions.

Methods

Respondents

Eligible respondents were adults aged ≥ 18 years who currently have, or previously have had, a confirmed diagnosis of haematological cancer made by a specialist and had sufficient English language skills to participate without an interpreter. Respondents who resided outside of Australia were excluded.

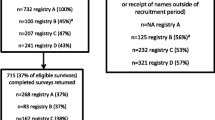

Recruitment

Respondents volunteered their participation in response to a study advertisement distributed via email and/or social media platforms by established national community groups (Leukaemia Foundation), professional member societies and working groups (Victorian COVID-19 Cancer Network), and clinical trial groups (Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group). Potential respondents were provided a link to an online information sheet, consent form, and survey. The study protocol was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 2,057,125.1).

Measures

An online cross-sectional survey was conducted from 22 July to 19 August 2020 and was used to collect the following information.

Demographic characteristic

Data on age, gender, postcode, marital status, education level, employment status, and number of dependants living in the home during the COVID-19 pandemic were collected. Residential postcode was used to classify respondents’ location (Major cities/Inner regional/Outer regional/Remote/Very remote) as per the Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) [19].

Medical characteristics

Information regarding respondents’ primary diagnosis, date of diagnosis, treatment, disease status, pre-existing health conditions, and type of hospital managing respondents’ care was collected.

Cancer care experience

Four questions were designed by the research team to better understand the care experiences of respondents during the pandemic (see Table 1). Questions explored opportunities for family support, access to care, perceived adequacy of access to support, and ability to maintain contact with the health care team.

Financial concerns

Two items were designed to explore respondents’ financial wellbeing during the pandemic, including whether they had lost income due to lockdown measures (Table 1).

Perceived risk and impact of COVID-19 on cancer management

Five questions were designed to investigate respondents’ concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on their own health and their perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 (Table 1).

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler 10-item assessment (K10) [20]. Respondents indicated the extent to which they experienced each emotional state since the beginning of the pandemic using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“None of the time”) to 5 (“All the time”). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.92, indicating a high level of internal consistency. Scores were divided into three categories representing mild (range 20–24), moderate (range 25–29), and severe psychological distress (range 30–50) [20].

Unmet supportive care needs

Respondents’ perceived needs during COVID-19 were captured by the subdomains Health system and Information needs (11 items) and Patient care and Support needs (5 items) of the short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34) [21]. The SCNS-SF34 had excellent internal consistency in this specific sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.97). The SCNS-SF34 uses a 5-point scale to measure unmet need: 1 = No need—not applicable; 2 = No need—satisfied; 3 = Low need; 4 = Moderate need; and 5 = High need. In line with previous research [21], responses 1 and 2 were re-coded as 0 (“No need”) and subsequent categories were re-scored accordingly 1 (“Low need”), 2 (“Moderate need”), and 3 (“High need”).

Fear of cancer recurrence

Respondents who had completed treatment and were in remission were asked to complete the 9-item Severity subscale of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI) [22]. This subscale evaluates the severity of intrusive thoughts associated with respondents’ fears about the possibility that cancer could return or progress on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“A great deal”). The accepted cut-off score for clinical FCR is 13. The FCRI had acceptable internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

Data analysis

Survey data were collected in Qualtrics and de-identified prior to being exported to SPSS (V26.0, IBM SPSS) for analysis. Respondents who did not meet eligibility criteria (n = 1) were removed from the data set, leaving only eligible respondents for the data analysis. Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, means, and standard deviations) were calculated. Demographic (age, gender, location, education, employment, dependants living at home), key clinical (diagnosis, time since diagnosis, treatment, disease status, pre-existing health conditions, private/public hospital), and COVID-19-related factors (cancer care experience during pandemic, financial concerns, risk and impact of COVID-19 on cancer management) were considered as potential correlates of three dependent variables: psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and FCR. Additionally, psychological distress was included as a potential correlated factor in the unmet supportive care needs and FCR models, and unmet needs was included as a potential correlated factor in the FCR and psychological distress models to examine the bidirectional relations between these variables [23]. Univariate linear regressions were conducted to identify potential correlates of psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and FCR. All variables significant at p < 0.05 were subsequently included in multiple linear regression models to determine their relative contribution to each of the dependent variables. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used to assess for multicollinearity.

Moderation analyses were carried out to further identify high-risk groups and explored the effects of gender (1 = men, 2 = women), location (1 = major cities, 2 = regional), age (treated as continuous), marital status (1 = single, 2 = married/defacto), education (1 = < tertiary, 2 = tertiary), and employment status (1 = employed, 2 = unemployed). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons given the exploratory nature of this study.

Results

Respondent characteristics

A total of 394 respondents aged 20 to 84 years (mean ± standard deviation (SD): 60.4 years ± 12.8) participated in this study (Table 2). Respondents were evenly divided between major cities (50%) and regional areas (50%). The ratio of men (53%) to women (47%) was relatively even and most were married (71%). Lymphoma (34%) and leukaemia (27%) were the most common haematological cancers reported. Over half (53%) of all respondents had received a haematological cancer diagnosis within the previous three years. In terms of stage of treatment, 43% were currently receiving ongoing, or maintenance treatment while 37% were in remission.

Psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and fear of cancer recurrence

Descriptive statistics for the dependent variables of psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and FCR are presented in Table 3. Thirty-five percent of respondents (n = 138) had elevated scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress scale, with 17% had scores suggestive of mild distress, 8% had scores suggestive of moderate distress, and 9% had scores suggestive of severe distress. Overall, 32% (n = 128) of respondents reported experiencing at least one unmet moderate or high need; 28% reported at least one unmet moderate or high need in the Health system and Information domain and 24% reported at least one unmet moderate or high need in the Patient care and Support domain. The most prevalent unmet needs were (i) having access to professional counselling (15%), (ii) being given information about test results as soon as feasible (15%), and (iii) being treated like a person (15%). Of those who had completed treatment and were in remission (n = 134), all respondents reported some degree of FCR, with 95% reporting clinical FCR.

Financial concerns

In terms of financial wellbeing during the pandemic, 26% of respondents had lost income and 29% indicated their financial concerns had been worse compared to the period before the outbreak.

Perceived risk and impact of COVID-19 on cancer management

Regarding the perceived adequacy of measures used to prevent transmission of COVID-19 in hospitals, 61% of respondents expressed some degree of concern (32% ‘a little bit concerned’, 15% ‘moderately concerned’, 8% ‘quite concerned’, 6% ‘very concerned’). Regarding their concerns about access of hospital staff to protective equipment to prevent COVID-19 transmission, 62% of respondents reported some degree of concern (29% ‘a little bit concerned’, 13% ‘moderately concerned’, 9% ‘quite concerned’, 11% ‘very concerned’). When asked how concerned they were about the impact of COVID-19 on their cancer management, 70% respondents reported some degree of concern (33% ‘a little bit concerned’, 19% ‘moderately concerned’, 12% ‘quite concerned’, 6% ‘very concerned’).

Cancer care experience

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 35% of respondents indicated they had limited opportunity for family support, and 21% had been restricted in accessing care due to travel bans. Regarding their care team, the majority of respondents felt they had maintained good contact (80%) and received adequate support (71%).

Factors associated with psychological distress

Online Resource 1 presents the factors found in univariate regression analyses to be significantly associated with psychological distress during the pandemic. These factors were entered simultaneously in a multiple regression model (adjusted R2 = 0.37, F(11, 324) = 18.63, p < 0.001; Table 4). VIF was < 10 indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue. Six of the factors remained significant, collectively explaining 35% of the variance in psychological distress. Specifically, unmet needs, pre-existing health conditions, younger age, financial concerns, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and living in a regional area were associated with greater psychological distress during the pandemic.

Moderation analyses revealed that (i) age moderated the relationship between financial concerns and psychological distress (B = 0.09, 95% CI = 0.03, 0.16, t = 2.72, p = 0.007), such that the association between financial concerns and distress was stronger in younger people compared to older people, and (ii) marital status moderated the relationship between perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 and higher psychological distress (B = -0.55, 95% CI = -0.91, -0.18, t = − 2.94, p = 0.004), such that the association between perceived risk of COVID-19 and distress was higher among those who were single compared to those who were married.

Factors associated with unmet supportive care needs

Online Resource 1 presents the factors found in univariate analyses to be significantly associated with unmet supportive care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors were entered simultaneously into a multiple regression model (adjusted R2 = 0.22, F(8, 331) = 12.89, p < 0.001; Table 4). VIF was < 10 indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue. Five of the factors remained significant, collectively explaining 22% of the variance in unmet supportive care needs. Psychological distress, lost income, perceived inadequate support from care team, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and being a woman were found to be significantly associated with greater unmet supportive care needs during the pandemic.

Moderation analyses revealed that (i) gender moderated the relationship between psychological distress and unmet needs (B = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.18, 0.73, t = 3.25, p = 0.001), such that the association between psychological distress and unmet needs was stronger in women than in men, and (ii) age moderated the relationship between lost income and unmet needs (B = − 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.09, -0.00, t = − 2.06, p = 0.039), such that the association between lost income and unmet needs was stronger in younger people compared to older people.

Factors associated with fear of cancer recurrence

Online Resource 1 presents the factors found in univariate analyses to be significantly associated with higher FCR during the COVID-19 pandemic among respondents in remission. These factors were entered simultaneously into a multiple regression model (adjusted R2 = 0.29, F(5, 120) = 11.21, p < 0.001; Table 4). VIF was < 10 indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue. Two of the factors remained significant, collectively explaining 28% of variance in FCR. Specifically, psychological distress and concern about the impact of COVID-19 on cancer management were associated with greater FCR during the pandemic. No significant moderators were identified.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the psychological issues experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic by haematological cancer patients and to identify correlated factors to inform the development of appropriate interventions. In this cross-sectional study, we found a high prevalence of psychological distress and unmet supportive care needs, which was much higher than results obtained from two previous studies involving Australian haematology patients during non-pandemic times [24, 25]. The high prevalence rates observed in our study might be attributable to the decline in the number of patients attending routine appointments during the pandemic [4]. Clinicians are usually a patient’s first and most influential source of information and support, and patients who have a strong alliance with their clinician have been shown to have higher levels of psychological wellbeing [26]. With fewer face-to-face clinic visits, patients may have missed out on the valuable clinical information and emotional support provided by their clinician, thereby heightening distress and increasing need for supportive care. It is worth noting, however, that these prior studies involved probability-based samples while the present study adopted a self-selection recruitment method. These distinct methodologies may also have contributed to the difference in prevalence rates. Nevertheless, our results highlight a need to be vigilant in screening for and managing distress and unmet needs. Consideration should be given to screening remotely during pandemic times when face-to-face clinical care is limited.

FCR was particularly prominent among respondents in the present study, with nearly all (95%) of those in remission reporting clinical levels of FCR. While FCR is arguably one of the most common issues among cancer survivors, the prevalence among this sample is significantly higher than that previously seen in survivors of solid cancers and haematological cancers in non-pandemic times [27, 28]. Therefore, the pandemic provides new urgency to respond to fears or worries patients may have about the possibility that their cancer will return or progress. FCR is an important concern to address as it is associated with high rates of depression and greater health care utilisation [29], and it does not appear to abate over time [30]. Greater validation of patients’ concerns and enhanced routine screening to determine the severity of FCR and the need for specialised treatment of FCR is critical. These efforts may enable the identification of patients with severe FCR who may benefit from referral to expert psycho-oncology staff who can apply evidence-based interventions that have emerged to address this condition. A single-item screening instrument has recently been developed for this purpose [31]. This tool is recommended as a rapid screen which can be followed with more detailed assessment. This is likely to be especially useful during crisis events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when clinical contact is limited and there is increased pressure on service delivery.

Unmet needs emerged as a key contributor to psychological distress among those surveyed in the present study. These findings are in line with previous research reporting positive associations between unmet needs and psychological morbidity among haematological cancer patients [32]. The widespread disruptions to accessing cancer care services during the pandemic may explain why ‘having access to professional counselling’, ‘being given information about test results as soon as feasible’, and ‘being treated like a person’ were the three highest ranked needs in this study. Moreover, the pandemic has likely heightened these needs due to travel restrictions posing additional barriers to accessing care, which was a concern reported by at least one in five (21%) respondents in this study. Our results suggest that attending to these needs among haematological cancer patients constitutes a potential means of reducing psychological distress.

Our results highlight the increased financial hardship faced by haematology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. At least one in four respondents indicated they had lost income as a result of the pandemic and had increased financial concerns. Lost income was associated with greater unmet needs, while financial concerns were associated with greater psychological distress. These associations underscore existing literature suggesting financial stress is a relatively powerful predictor of distress among haematological cancer patients, who are particularly vulnerable to these difficulties due to the expensive and prolonged nature of treatments such as HSCT that can lead to extended time away from work [32,33,34]. Moreover, this study found that the associations between (i) financial concerns and psychological distress and (ii) lost income and unmet needs were stronger in younger people compared to older people, indicating that this subgroup of patients may particularly benefit most from support in accessing financial assistance. During the pandemic, working-age haematology patients may have lost their job, or possibly had to weigh the benefits of work with potential increased risk of contracting COVID-19. While the long-term impact of the pandemic on people with haematological cancers requires further research, the increased hardship reported by respondents in this study has immediate implications for those who are involved in their care since it could lead to discontinued cancer care and more serious psychological problems, including depression and anxiety [35]. Clinicians can help by using validated screening tools, such as the 11-item COST-FACIT [36], to identify patients at high risk who may benefit from additional financial advocacy resources and referral to targeted interventions.

This study found evidence of positive associations between perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 and both psychological distress and unmet needs, with the association between perceived risk and distress stronger among single persons. Additionally, a positive association was observed between concern about the impact of COVID-19 on cancer management and FCR among respondents in remission. In Australia, messages communicating the dangers of COVID-19 have led to unintended declines in patient presentations for cancer management appointments [4]. Several community-based cancer organisations have already taken proactive steps to help restore the delivery of cancer care through social media campaign initiatives. For example, the “Don’t delay” and “Here for you” campaigns encourage patients to follow-up on health concerns and access cancer support [37, 38]. Our findings shed light on previous reports of reductions in patients accessing cancer care during the pandemic and demonstrate the importance of reassuring patients about the safety of clinical facilities and informing them of the availability and effectiveness of telehealth appointments [39]. This may help to reduce fears of contracting COVID-19 and restore much needed cancer care.

Building upon previous research [40], the present study found higher levels of distress amongst regional compared to urban respondents. In recent years, there have been increased efforts to enable access to cancer services for regional haematological cancer patients, since much of their needed care is only offered in urban treatment centres [15]. However, unwarranted variation in care for regional patients is an issue that continues to demand action, which has likely heightened during the pandemic due to travel restrictions posing additional barriers to accessing care.

Limitations

Several study limitations need to be considered. First, an eligibility requirement that respondents have sufficient English language skills is likely to have prevented the participation of individuals from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. Future research considering the needs of these individuals is critical. This is particularly important given the rapid uptake of telehealth consultations, which are less suited to CALD patients and may exacerbate inequalities that are already apparent in cancer care [15, 41]. Second, the present findings should be interpreted with caution due to the potential for bias resulting from our self-selection recruitment method. Third, as this study was cross-sectional, causative links cannot be assumed and require further investigation in prospective studies. Fourth, the heterogenous sample of haematological cancer patients surveyed conflates a range of haematological cancer subtypes, types and number of treatments carried out, and risk of progression over time. In this sample, both aggressive and indolent subtypes and treatments with and without curative intent can be found, which have corresponding implications for assessing FCR. As such, the prevalence of psychological distress, unmet needs, and FCR associated with specific haematological cancer subtypes and treatments may not be elucidated in this study, and we cannot generalise the results to all haematological cancer patients. Finally, this study did not include detailed questions about patients’ perspectives or experiences resulting from receiving care via telehealth. A qualitative study examining the perceived value of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic is currently ongoing.

Conclusion

The present study is one of the first to explore the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress, unmet needs, and FCR in haematological cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results indicate that respondents experience high levels of distress and unmet needs, and that the majority in remission experience clinical FCR. These findings highlight the need for supportive interventions to assist haematological cancer patients to better manage distress, unmet needs, and FCR, which is particularly important during pandemic times when face-to-face clinical care is limited. The correlated factors identified in this study can be used to inform the development of appropriate support interventions and target those most in need, including financial concerns, lost income, younger age, living in a regional area, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and concern about the impact of COVID-19 on the management of haematological cancers. It is hoped that the present findings encourage much needed efforts to minimise major disruptions to cancer care and mitigate the longer-term psychological impact on people with haematological cancers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

N/A

References

Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, Shete S, Hsu C-Y, Desai A, de Lima Lopes D Jr (2020) Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet 395(10241):1907–1918

Weinkove R, McQuilten Z, Adler J, Agar M, Blyth E, Cheng A, Conyers R, Haeusler G, Hardie C, Jackson C (2020) Managing haematology and oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim consensus guidance. Med J Aust 212(10):481–489. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50607

American College of Emergency Physicians (2020) COVID-19.https://www.emergencyphysicians.org/globalassets/emphysicians/all-pdfs/acep-mc-COVID19-april-poll-analysis.pdf. Accessed 28 November 2020

Monash Partners Comprehensive Cancer Consortium (2020) Victoria launches safe cancer care campaign for patients. https://www.monashpartnersccc.org/news/victoria-launches-safe-cancer-care-campaign-for-patients. Accessed 6 May 2020

Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RH, Louwman MW, van Nederveen FH, Willems SM, Merkx MA, Lemmens VE, Nagtegaal ID, Siesling S (2020) Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol 21(6):750–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5

Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, Purushotham A, Nolte E, Sullivan R, Rachet B, Aggarwal A (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol 21(8):1023–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, O’Sullivan DE, Booth CM, Sullivan R, Aggarwal A (2020) Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 371:m4087. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4087

Chen G, Wu Q, Jiang H, Zhang H, Peng J, Hu J, Chen M, Zhong Y, Xie C (2020) Fear of disease progression and psychological stress in cancer patients under the outbreak of COVID-19. Psycho-oncol 29:1395–1398. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5451

Swainston J, Chapman B, Grunfeld EA, Derakshan N (2020) COVID-19 lockdown and its adverse impact on psychological health in breast cancer. Front Psychol 11:2033. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02033

Edge R, Mazariego C, Li Z, Canfell K, Miller A, Koczwara B, Shaw J, Taylor N (2021) Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on cancer patients, survivors, and carers in Australia: a real-time assessment of cancer support services. Support Care Cancer:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06101-3

Leach CR, Kirkland EG, Masters M, Sloan K, Rees-Punia E, Patel AV, Watson L (2021) Cancer survivor worries about treatment disruption and detrimental health outcomes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosoc Oncol:1–16

World Ovarian Cancer Coalition, World Pancreatic Cancer Coalition, Lymphoma Coalition, Advanced Breast Cancer Global Alliance, Coalitions WBCP (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on cancer patient organisations https://worldovariancancercoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-impact-of-COVID-19-on-Cancer-Patient-Organisations-12th-June-2020-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 11 November 2020

Eichenberger EM, Soave R, Zappetti D, Small CB, Shore T, van Besien K, Douglass C, Westblade LF, Satlin MJ (2019) Incidence, significance, and persistence of human coronavirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 54(7):1058–1066. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-018-0386-z

Lee LY, Cazier J-B, Starkey T, Briggs SE, Arnold R, Bisht V, Booth S, Campton NA, Cheng VW, Collins G (2020) COVID-19 prevalence and mortality in patients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 21(10):1309–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30442-3

Leukaemia Foundation (2020) National Strategic Action Plan for Blood Cancer. https://www.leukaemia.org.au/national-action-plan. Accessed 19 November 2020

Purtill J (2020) Graham is waiting on lifesaving stem cell treatment. Coronavirus is stopping delivery. Australian Broadcasting Company. https://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/stem-cell-transplants-coronavirus/12070468. Accessed 6 May 2020

Mengling T, Rall G, Bernas SN, Astreou N, Bochert S, Boelk T, Buk D, Burkard K, Endert D, Gnant K, Hildebrand S, Köksaldi H, Petit I, Sauter J, Seitz S, Stolze J, Weber K, Weber M, Lange V, Pingel J, Platz A, Schäfer T, Schetelig J, Wienand E, Geist S, Neujahr E, Schmidt AH (2020) Stem cell donor registry activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: a field report by DKMS. Bone Marrow Transplant. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-020-01138-0

Lloyd M (2020) Australia scrambles to save blood cancer patients as COVID-19 border closures delay foreign cell transplants. ABC News.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-24/covid-19-border-closure-forces-stem-cell-transplant-workaround/12688108. Accessed 23 November 2020

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Volume 5 Remoteness Structure. ABS. http://www.abs.gov.au. Accessed 4 September 2020

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand S-LT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch General Psychiatry 60(2):184–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C (2009) Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract 15(4):602–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01057.x

Simard S, Savard J (2009) Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 17(3):241–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0444-y

Lebel S, Rosberger Z, Edgar L, Devins GM (2009) Emotional distress impacts fear of the future among breast cancer survivors not the reverse. J Cancer Surviv 3(2):117–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-009-0082-5

Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW, Carey ML, Paul C, Williamson A, Bradstock K, Campbell HS (2016) Prevalence and associates of psychological distress in haematological cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24(10):4413–4422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3282-3

Boyes AW, Clinton-McHarg T, Waller AE, Steele A, D’Este CA, Sanson-Fisher RW (2015) Prevalence and correlates of the unmet supportive care needs of individuals diagnosed with a haematological malignancy. Acta Oncol 54(4):507–514. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2014.958527

Trevino KM, Fasciano K, Prigerson HG (2013) Patient-oncologist alliance, psychosocial well-being, and treatment adherence among young adults with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 31(13):1683. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.46.7993

Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, Beith J, Stuart-Harris R, Grossi M, Capp A, Dalley D, Committee FSA (2012) Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support Care Cancer 20(11):2651–2659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1371-x

Borreani C, Alfieri S, Farina L, Bianchi E, Corradini P (2020) Fear of cancer recurrence in haematological cancer patients: exploring socio-demographic, psychological, existential and disease-related factors. Support Care Cancer 28(12):5973–5982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05434-9

Mutsaers B, Jones G, Rutkowski N, Tomei C, Leclair CS, Petricone-Westwood D, Simard S, Lebel S (2016) When fear of cancer recurrence becomes a clinical issue: a qualitative analysis of features associated with clinical fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24(10):4207–4218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3248-5

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G (2013) Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv 7(3):300–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

Rudy L, Maheu C, Körner A, Lebel S, Gélinas C (2020) The FCR-1: Initial validation of a single-item measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Psycho-Oncol 29(4):788–795. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5350

Tzelepis F, Paul CL, Sanson-Fisher RW, Campbell HS, Bradstock K, Carey ML, Williamson A (2018) Unmet supportive care needs of haematological cancer survivors: rural versus urban residents. Ann Hematol 97(7):1283–1292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-018-3285-x

Hamilton JG, Wu LM, Austin JE, Valdimarsdottir H, Basmajian K, Vu A, Rowley SD, Isola L, Redd WH, Rini C (2013) Economic survivorship stress is associated with poor health-related quality of life among distressed survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psycho-Oncol 22(4):911–921. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3091

Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Hahn T, Lee SJ, McCarthy PL, Ammi M, Denzen E, Drexler R, Flesch S, James H (2013) Pilot study of patient and caregiver out-of-pocket costs of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 48(6):865–871. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.248

Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A (2013) Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psycho-oncol 22(4):745–755. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3055

De Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, Wroblewski K, Ratain MJ, Cella D, Daugherty C (2014) The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer 120(20):3245–3253. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28814

Cancer Council Victoria (2020) Don't delay campaign resources. https://www.cancervic.org.au/get-support/covid-19/dont-delay/assets.html. Accessed 17 November 2020

United Kingdom National Health Service (2020) Don’t delay seeing a GP if you have signs and symptoms of cancer. https://www.leedsccg.nhs.uk/news/dont-delay-seeing-a-gp-if-you-have-signs-and-symptoms-of-cancer. Accessed 17 November 2020

Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Wilson HL, Patterson P (2016) Consensus among international ethical guidelines for the provision of videoconferencing-based mental health treatments. JMIR Mental Health 3(2):e17. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5481

Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, White K, Underhill C, Goldstein D (2012) Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 20(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1270-1

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2020) Fears for culturally and linguistically diverse patients avoiding healthcare due to COVID-19.https://www.racgp.org.au/gp-news/media-releases/2020-media-releases/july-2020/fears-for-culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-pa. Accessed 2020 1 December

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants who willingly participated in this study during a challenging time. The authors also thank community organisations for referring participants to the study.

Funding

This work was supported by a private donation made to the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences to support research into the impact of COVID-19 on cancer patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Nienke Zomerdijk, Michelle Jongenelis, and Camille E. Short. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Nienke Zomerdijk and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 2057125.1) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Participants provided informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zomerdijk, N., Jongenelis, M., Short, C.E. et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and fear of cancer recurrence among haematological cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic . Support Care Cancer 29, 7755–7764 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06369-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06369-5