Abstract

Purpose

The actual state of mental health care use and related factors in adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients with cancer is not well understood in Japan. This study aimed to (1) examine the actual state of mental health care use among AYA patients with cancer and (2) describe socio-demographic and related factors associated with mental health care use.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of AYA patients with cancer aged 15–39 who first visited the National Cancer Center Hospital in Japan (NCCH) between January 2018 and December 2020. Logistic regression was used to analyze the association between social background characteristics and mental health care use. The association between the patient's course of cancer treatment and mental health care use was analyzed to help identify which patients might benefit from early mental health intervention.

Results

Among 1,556 patients, 945 AYA patients with cancer were registered. The median age at the time of the study was 33 years (range, 15–39 years). The prevalence of mental health care use was 18.0% (170/945). Age 15–19 years, female gender, urogenital cancer, gynecological cancer, bone or soft tissue cancer, head and neck cancer, and stage II–IV disease were associated with mental health care use. Regarding treatment, palliative treatment, chemotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were associated with mental health care use.

Conclusion

Factors associated with mental health care use were identified. Our findings potentially contribute to psychological support interventions for AYA patients with cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients with cancer are defined as those aged 15 to 39 years at the time of initial cancer diagnosis [1]. In the United States, approximately 87,000 AYAs are newly diagnosed with cancer each year, approximately 4.5% of all people diagnosed with cancer [2]. In Japan, approximately 20,000 AYAs are newly diagnosed with cancer each year, approximately 2.3% of all people diagnosed with cancer [3].

AYA patients with cancer are complex and vulnerable as a result of the intersection of disease and developmental stage [4]. AYA patients with cancer are in various challenging situations related to physical and cognitive development, identity, body image, autonomy, and employment [5, 6]. A diagnosis of cancer could significantly disrupt or delay these aspects of development.

Cancer treatment can interfere with education or employment plans [7], which might cause great distress for AYA patients with cancer. Research indicates that AYA patients with cancer report significantly poorer physical and mental health than matched controls [8] and that young adult patients with cancer report more negative psychosocial outcomes than older patients [9].

Previous questionnaire surveys have evaluated psychological distress and related factors in AYA patients with cancer. The related factors were reported to be younger or older age, female gender, digestive system cancer, breast cancer, head and neck cancer, chemotherapy or radiotherapy, not being in a partnership, being divorced, lower monthly income, lower education level, lower exercise intensity, longer time since diagnosis, anxiety, depression, and cancer- and treatment-related adverse late outcomes [10,11,12,13].

In a questionnaire survey in Japan, pain, decrease in income after a cancer diagnosis, experience of negative changes at work or school after a cancer diagnosis, and poor social support were reported to be significantly associated with psychological distress [14]. Furthermore, AYA patients with cancer in Japan have a three-fold higher risk of major depressive disorder within 6 months before and 12 months after cancer diagnosis compared with cancer-free controls [15]. A previous study found that AYA patients with cancer aged 15–24 years have a higher risk of suicide than cancer-free controls [16].

The international clinical practice guidelines from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group [17] strongly recommend mental health surveillance for all survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers at every follow-up visit and prompt referral to mental health specialists when problems are identified. The recommendations reflect the necessity of mental health surveillance as part of comprehensive survivor-focused health care.

In a previous study [6], AYA patients with cancer were more likely to demonstrate psychological distress than individuals without cancer. Nevertheless, few survivors might be receiving professional mental health care. Survivors need great access to mental health screening and counseling to address the current gaps in care delivery. A previous study reported that there is a strong need for psycho-oncological interventions designed to improve mental health in AYA patients with cancer at all stages of medical care [18].

In Japan, since the number of AYA patients with cancer at each hospital is small and the primary cancer site varies [19], it is difficult for medical staff to gain experience related to providing medical care and support to AYA patients with cancer. There are marked differences in support for AYA patients with cancer among hospitals [20].

In order to help medical staff identify who is in need of psychosocial intervention and when to intervene most effectively, real-world data about mental health care use and related factors for AYA patients with cancer are needed. However, these data are not well understood in Japan. This study aimed to (1) examine the actual state of mental health care use of AYA patients with cancer and (2) describe socio-demographic and related factors associated with mental health care use.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of AYA patients with cancer who first visited the National Cancer Center Hospital in Japan (NCCH) between January 2018 and December 2020. NCCH has a department of psycho-oncology that consists of psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and nurses specializing in liaison consultation. The mental health professionals of this department provide mental health care to NCCH patients. We defined mental health care in this study as any medical care provided to both outpatients and inpatients by the mental health professionals with or without a psychiatric diagnosis. An electronic database was used to identify mental health care use and related factors for AYA patients with cancer.

To more directly examine the factors associated with mental health care use and with cancer incidence, the eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosis of cancer and between 15 and 39 years at the time of the study; (2) duration from diagnosis of cancer to first NCCH visit of less than 1 year; (3) no history of mental health care use, including at other hospitals; and (4) no use of any mental health care at other hospitals during the study period. The eligibility criteria (3) and (4) were set because we were concerned that if those patients were included in this study, it would include patients who used mental health care for factors other than cancer. In addition, this study was a retrospective medical record survey, which made it difficult to collect information on history of mental health care use including at other hospitals and use of any mental health care at other hospitals during the study period.

The database included demographic variables such as age, gender, social status, cancer type (primary site), cancer stage, days from diagnosis of cancer to first NCCH visit, treatment setting (at 1 month after the first visit), treatment type (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation), smoking, drinking, having spouses or partners, having children, living status, and mental health care use less than 1 year after diagnosis of cancer.

For patients who used mental health care less than 1 year after diagnosis of cancer, the database also included demographic variables such as psychiatric diagnoses according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) [21], days from each diagnosis of cancer to mental health care use, treatment setting (where they used mental health care), occupation of mental health care providers, type of medication (sleeping pills, anxiolytic, antipsychotic, antidepressant, or other), number of mental health care visits, and outcome. We defined Group A as patients aged 15–24 years (adolescents and older adolescents) and Group YA as patients aged 25–39 years (young adults) based on the definition of a previous study in Japan [19]. Regarding the content of mental health care use, Groups A and YA were analyzed separately to clarify the differences among them.

This study was approved by the NCCH Ethics Committee (approval number: 2019-215). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective cohort design. Opt-out information was published on the NCCH website. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Sample size calculations

We planned to perform a multiple regression analysis to examine the factors related to mental health care use. We calculated that more than 10 times as many study participants as the number of independent variables would be required [22]. Considering the possibility of missing data, the planned number of study participants was more than 200.

Statistical analysis

First, we used descriptive statistics. Second, the prevalence of mental health care use among all participants was calculated. Third, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with logistic regression to examine associations between demographic variables and the prevalence of mental health care use. All demographic variables were entered as independent variables. The association between patients' social background characteristics and mental health care use was analyzed to help identify which patients might benefit from early mental health intervention. The association between the patient's course of cancer treatment and mental health care use was analyzed. A forced entry method was used to explore factors related to mental health use. In the logistic regression analysis, cases with even one missing value were excluded from the analysis. Fourth, to compare the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in Groups A and YA, the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used, as appropriate. Data were analyzed with SPSS version 27.0 (IBM). All tests were two-tailed, with a p-value of <0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

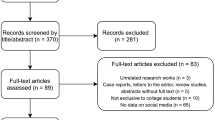

Among 1,556 patients, 945 AYA patients with cancer were registered in the database in August 2021 (Fig. 1). The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Median age at the time of the study was 33 years (range, 15–39 years). Cancer diagnoses included gastrointestinal cancer (n=171; 18.1%), breast cancer (n=162; 17.1%), lung cancer (n=124; 13.1%), gynecological cancer (n=86; 9.1%), head and neck cancer (n =84; 8.9%), and other (n =318; 33.7%). The most common stage at diagnosis was stage I (n=207, 21.9%), followed by stage II (n=129, 13.6%). The most common treatment type was curative (n=438, 46.4%). The prevalence of mental health care use was 18.0% (170/945).

Factors associated with mental health care use

We used logistic regression to compare socio-demographic and medical factors between patients with and without mental health care use. The association between patients' social background characteristics and mental health care use was analyzed in 426 patients with no missing values. Age 15–19 years, female gender, urogenital cancer, gynecological cancer, bone or soft tissue cancer, head and neck cancer, and stage II–IV disease were associated with mental health care use (Table 2). The association between the patient's course of cancer treatment and mental health care use was analyzed in 627 patients with no missing values. Regarding treatment type, palliative treatment, chemotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were associated with mental health care use (Table 3).

Mental health care use in AYA patients with cancer

Details about mental health care use are shown in Table 4. Among 170 patients who used mental health care, 71.8% (n=122) of patients did not have a psychiatric diagnosis. The most common duration from diagnosis of cancer to mental health care use was less than 3 months (n=103, 60.6%). The most common treatment type was curative (n=92, 54.1%). The most common occupation who provided support was psychotherapist (n=132, 77.6%). Among 75 patients who were prescribed psychotropic drugs, the most common psychotropic drug type was sleeping pills (n=34, 45.3%). The most common number of visits ranged from 2 to 5 (n=62, 36.5%). The most common outcome was improvement (n=132, 77.6%).

We compared the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in Groups A and YA using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Group A had a significantly higher percentage of patients with no psychiatric diagnosis relative to Group YA. A significantly higher percentage of patients in Group A was supported by psychotherapist, whereas a significantly higher percentage of patients in Group YA was supported by psychiatrist. Consistent with this, Group YA had more patients who were treated with medication than Group A.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the actual state of mental health care use of AYA patients with cancer and described the socio-demographic and related factors associated with mental health care use in Japan. This study has several strengths. First, our findings suggested that urogenital cancer, gynecological cancer, bone or soft tissue cancer, and palliative treatment were associated with mental health care use, which had not been previously reported. Second, there were more patients with sleep-wake disorders in this study than in a previous study [37], followed by trauma-related and stressor-related disorders. These new points should be noted when supporting AYA patients with cancer. Finally, our findings suggested that age 15–19 years, female gender, head and neck cancer, stage II–IV disease, chemotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are associated with mental health care use. Although these findings were consistent with those of previous studies, it was important to note that these data were from the real world, not questionnaire surveys.

The prevalence of mental health care use in AYA patients with cancer (age range, 15–39 years) in this study was 18.0% (170/945). On the other hand, although the data were from survivors, not patients, approximately 30% of cancer survivors in Japan (age range: 34–79 years) reportedly use mental health care [23]. Although our findings suggest that mental health care use among AYA patients with cancer is lower than among other generations, this does not mean that AYA patients with cancer have a lower need for mental health care. In Japan, more than 70% of AYA patients with cancer reported unmet supportive care needs, mostly psychological [24]. These findings suggest that AYA patients with cancer have unmet mental health care needs. This is consistent with the findings of a previous study [6]. We need to work on addressing the current gaps in mental health care delivery.

Age 15–19 years and female gender were patient characteristics associated with mental health care use. Although correlations between age and psychological distress in previous studies were inconsistent [10, 13], younger age (15–19 years) was associated with mental health care use in this study. This finding was consistent with that of a previous study in China [13]. In younger AYA patients with cancer, the body and mind are still growing and developing; younger AYA patients with cancer might have special needs and challenges in fertility preservation, parenting, schooling, and employment compared to patients of other ages. Therefore, we need to pay much more attention to younger AYA patients with cancer. Parents have described their adolescent's cancer-related distress as the most problematic symptom, contributing to symptom burden on both adolescent patients and their parents [25]. Therefore, parental concerns might have led to mental health care use by adolescents with cancer. Female gender was associated with mental health care use. This was consistent with the finding that female gender is associated with psychological distress [12]. Female patients with cancer were reported to be more affected by depression and anxiety [26]; this tendency might lead to mental health care use more than in males.

Urogenital cancer, gynecological cancer and bone or soft tissue cancer were associated with mental health care use in this study, but were not associated with mental health care use in from a previous study [13]. This difference might be related to the impact of cancer incidence and cancer treatment on fertility. In gynecologic and urologic cancers, the cancer has a direct effect on fertility. In bone or soft tissue cancer, the risk of chemotherapy affecting fertility has been reported [27, 28]. Patients with cancer in Japan request information about fertility preservation and psychological support [29]. However, a system for providing explanatory materials for fertility preservation and encouraging cooperation at the physician and hospital levels are insufficient support for AYA patients with cancer [30]. Therefore, these cancer types might be related to mental health care use. Head and neck cancer was a related factor, as in a previous study [13]. The prevalence of depression in patients with head and neck cancer is higher than in other types of cancer [31, 32]. Head and neck cancer is a strong risk factor for suicide [33]. Patients with head and neck cancer are prone to significant psychological strain due to pain, dysfunction, compression by the tumor, communication difficulties, and changes in appearance, in addition to the general psychological problems associated with cancer. It was considered a type of cancer that requires adequate attention in terms of psychological care in the AYA generation.

Stage II–IV disease was associated with mental health care use. As the stage increased, so did the OR for mental health use. In general, the higher the stage, the worse the prognosis for cancer, so this result is reasonable. These findings were consistent with the presence of a significant association between depression and advanced or metastatic cancer [34].

Palliative treatment was associated with mental health care use. Although not reported in previous studies, it is easy to imagine patients feeling depressed because there is no radical cure to be sought.

Chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were associated with mental health care use. These were consistent with the findings of previous studies [13, 35]. It has been reported that patients with cancer experience anxiety and depression during chemotherapy [36]. Many AYA patients with cancer who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation have described unmet psychological needs [35].

Details about mental health care use were compared with the results of a previous study of patients with cancer in Japan [37]. In this study, there were more patients with sleep-wake disorders (39.6%, 19/48) than in that previous study, but fewer patients with delirium, which is included in the category of neurocognitive disorders. Various studies [38,39,40,41] have shown that delirium in patients with cancer is associated with older age, which is consistent with our findings with younger patients. Consistent with the high prevalence of sleep-wake disorders, sleeping pills were the most frequently prescribed medication. Because of the high rate of sleep disturbances, we need to pay close attention to the sleep of AYA patients with cancer.

After sleep-wake disorders, the most common diagnosis was trauma-related and stressor-related disorder (29.2%, 14/48). The most common trauma-related and stressor-related disorder diagnosis was adjustment disorder. A meta-analysis reported that psychotherapy is effective in patients with cancer with depressive symptoms, including those with adjustment disorders [34]. Psychotherapy is a specialty of the psychotherapist, the most common occupation who provided support in this study. This result suggests that the psychotherapist is essential in the mental health care of AYA patients with cancer. In Japan, even large hospitals have shortages of psycho-oncologists [19]. Therefore, psychotherapists might play a role in filling these shortages.

In Group YA, 61.5% of patients had no psychiatric diagnoses whereas 90.2% of patients in Group A had no psychiatric diagnoses. In Group YA, 69.7% of patients were supported by a psychotherapist, compared with 91.8% of patients in Group A. These results suggest that there is a great need for psychotherapists to treat adolescents. This may be due to the fact that psychotherapists provided support for psychological reactions after bad news at NCCH.

This study has several limitations. First, this study had a single-center retrospective cohort design. Results might not be generalizable to other settings because the NCCH support system for AYA patients with cancer was robust [42,43,44,45]. Further prospective multicenter studies are needed. Second, all data were collected retrospectively from medical records. The possibility of out-of-hospital mental health care use not documented by the health care provider cannot be ruled out. Third, there were several items that the information in the medical records did not reveal. Because cases with even one missing value were excluded from the analysis in the logistic regression analysis, the results in Tables 1, 2, and 3 were partially inconsistent. For example, although male had a higher percentage of mental health use in Table 1, it was female who were associated with mental health use in the logistic regression analysis. Furthermore, the final number of patients used in the logistic analysis was much smaller than the overall number of patients. The exclusion of cases with any missing value from the analysis may have biased the results. Fourth, because this study was a retrospective medical record survey, with many missing values and a small number of subjects for analysis in logistic regression, this study was unable to examine any difference in the related factors associated with mental health care use between Groups A and YA. Finally, low income was known to be associated with psychological distress in AYA cancer patients [10, 13, 14]. However, items related to economic aspects were not extracted in this study, as it was assumed that such items would be experientially less likely to be included in the medical records of NCCH. The next challenge is to focus on the economic aspects of AYA cancer patients. Finally, study participants were all Japanese. Careful consideration might be required when generalizing our findings to other races and ethnic groups. Despite these limitations, our findings potentially contribute to interventions that provide psychological support to AYA patients with cancer.

Conclusions

Factors associated with mental health care use were identified. Our findings potentially contribute to interventions that provide psychological support to AYA patients with cancer.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L et al (2018) Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 16(1):66–97. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0001

National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: cancer among adolescent and young adults (AYAs) (ages 15–39). http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html. Accessed 16 April 2022

Katanoda K, Shibata A, Matsuda T et al (2017) Childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer incidence in Japan in 2009-2011. Jpn J Clin Oncol 47(8):762–771. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyx070

Kwak M, Zebrack BJ, Meeske KA et al (2013) Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a 1-year longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol 31(17):2160–2166. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9222

Husson O, Zebrack BJ (2017) Perceived impact of cancer among adolescents and young adults: relationship with health-related quality of life and distress. Psycho-Oncology 26(9):1307–1315. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4300

Kaul S, Avila JC, Mutambudzi M et al (2017) Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 123(5):869–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30417

D’Agostino NM, Penny A, Zebrack B (2011) Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 117(10 Suppl):2329–2334. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26043

Phillips-Salimi CR, Andrykowski MA (2013) Physical and mental health status of female adolescent/ young adult survivors of breast and gynecological cancer: a national, population-based, case-control study. Support Care Cancer 21(6):1597–1604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1701-7

Stava CJ, Lopez A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R (2006) Health profiles of younger and older breast cancer survivors. Cancer 107(8):1752–1759. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22200

Kim MA, Yi J (2013) Psychological distress in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer in Korea. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 30(2):99–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454213478469

Xie J, Ding S, He S et al (2017) A prevalence study of psychosocial distress in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Nurs 40(3):217–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000396

Michel G, Francois C, Harju E et al (2019) The long-term impact of cancer: evaluating psychological distress in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in Switzerland. Psycho-Oncology 28(3):577–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4981

Duan Y, Wang L, Sun Q et al (2021) Prevalence and Determinants of Psychological Distress in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer: A Multicenter Survey. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 8(3):314–321. https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-5625.311005

Okamura M, Fujimori M, Goto S et al (2022) Prevalence and associated factors of psychological distress among young adult cancer patients in Japan. Palliat Support Care:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521002054

Akechi T, Mishiro I, Fujimoto S (2022) Risk of major depressive disorder in adolescent and young adult cancer patients in Japan. Psycho-Oncology 31(6):929–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5881

Gunnes MW, Lie RT, Bjørge T et al (2017) Suicide and violent deaths in survivors of cancer in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood-A national cohort study. Int J Cancer 140(3):575–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30474

Marchak JG, Christen S, Mulder RL et al (2022) Recommendations for the surveillance of mental health problems in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Lancet Oncol 23(4):e184–e196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00750-6

Geue K, Brähler E, Faller H et al (2018) Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial distress in German adolescent and young adult cancer patients (AYA). Pycho-Oncology 27(7):1802–1809. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4730

Ohara A, Furui T, Shimizu C et al (2018) Current situation of cancer among adolescents and young adults in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol 23(6):1201–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-018-1323-2

Nakayama H, Toh Y, Fujishita N et al (2020) Present status of support for adolescent and young adult cancer patients in member hospitals of Japanese Association of Clinical Cancer Centers. Jpn J Clin Oncol 50(11):1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa141

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5 (R)). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., pp 596–602

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E et al (1996) A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 49(12):1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3

Matsui T, Tanimukai H (2017) The use of psychosocial support services among Japanese breast cancer survivors. Jpn J Clin Oncol 47(8):743–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyx058

Okamura M, Fujimori M, Sato A et al (2021) Unmet supportive care needs and associated factors among young adult cancer patients in Japan. BMC Cancer 21(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07721-4

Pöder U, Ljungman G, von Essen L (2010) Parents' perceptions of their children's cancer-related symptoms during treatment: A prospective, longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage 40(5):661–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.012

Götze H, Friedrich M, Taubenheim S et al (2020) Depression and anxiety in long-term survivors 5 and 10 years after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 28(1):211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04805-1

Shin T, Kobayashi T, Shimomura Y et al (2016) Microdissection testicular sperm extraction in Japanese patients with persistent azoospermia after chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 21(6):1167–1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-016-0998-5

Levine J, Canada A, Stern CJ (2010) Fertility preservation in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(32):4831–4841. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8312

Takeuchi E, Shimizu M, Miyata K et al (2019) A Content Analysis of Multidimensional Support Needs Regarding Fertility Among Cancer Patients: How Can Nonphysician Health Care Providers Support? J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 8(2):205–211. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2018.0085

Maezawa T, Suzuki N, Takeuchi H et al (2022) Identifying Issues in Fertility Preservation for Childhood and Adolescent Patients with Cancer at Pediatric Oncology Hospitals in Japan. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 11(2):156–162. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2021.0088

Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T et al (2000) Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychologic distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer 88(12):2817–2823. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12<2817::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-n

McCaffrey JC, Weitzner M, Kamboukas D et al (2007) Alcoholism, depression, and abnormal cognition in head and neck cancer: a pilot study. Otolaryngoloy-Head and Neck Surgery 136(1):92–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2006.06.1275

Zaorsky NG, Zhang Y, Tuanquin L et al (2019) Suicide among cancer patients. Nature. Communications 10(1):207. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08170-1

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H et al (2011) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 12(2):160–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X

Pulewka K, Strauss B, Hochhaus A et al (2021) Clinical, social, and psycho-oncological needs of adolescents and young adults (AYA) versus older patients following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 147(4):1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-020-03419-z

Whisenant M, Wong B, Mitchell SA et al (2020) Trajectories of Depressed Mood and Anxiety During Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs 43(1):22–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000670

Tada Y, Matsubara M, Kawada S et al (2012) Psychiatric disorders in cancer patients at a university hospital in Japan: descriptive analysis of 765 psychiatric referrals. Jpn J Clin Oncol 42(3):183–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyr200

Ljubisavljevic V, Kelly B (2003) Risk factors for development of delirium among oncology patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 25(5):345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00070-7

Markar SR, Smith IA, Karthikesalingam A et al (2013) The clinical and economic costs of delirium after surgical resection for esophageal malignancy. Ann Surg 258(1):77–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828545c1

McAlpine JN, Hodgson EJ, Abramowitz S et al (2008) The incidence and risk factors associated with postoperative delirium in geriatric patients undergoing surgery for suspected gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 109(2):296–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.016

Mercadante S, Masedu F, Balzani I et al (2018) Prevalence of delirium in advanced cancer patients in home care and hospice and outcomes after 1 week of palliative care. Support Care Cancer 26(3):913–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3910-6

Ishiki H, Hirayama T, Horiguchi S et al (2022) A Support System for Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. JMA Journal 5(1):44–54. https://doi.org/10.31662/jmaj.2021-0106

Hirayama T, Fujimori M, Yanai Y et al (2022) Development and evaluation of the feasibility, validity, and reliability of a screening tool for determining distress and supportive care needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer in Japan. Palliat Support Care:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895152200092X

Hirayama T, Kojima R, Udagawa R et al (2022) A Questionnaire Survey on Adolescent and Young Adult Hiroba, a Peer Support System for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients at a Designated Cancer Center in Japan. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 11(3):309–315. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2021.0101

Hirayama T, Kojima R, Udagawa R et al (2022) A Hospital-Based Online Patients Support Program, Online Adolescent and Young Adult Hiroba, for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients at a Designated Cancer Center in Japan. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2021.0168

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the AYA patients with cancer who participated in this study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by a research fund from the Japan Health Research Promotion Bureau Research Fund (2020−B-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to study conception and design. Data preparation and analysis were performed by Takatoshi Hirayama, Ryo Okubo, and Satoru Ikezawa. Data collection was performed by Tomoko Mizuta. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Takatoshi Hirayama, Ryo Okubo, and Satoru Ikezawa. Shintaro Iwata and Tatsuya Suzuki commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Approval was granted by the National Cancer Center Institutional Review Board on April 23, 2020 (approval number, 2019-215).

Consent to participate and publish

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design. Opt-out information was published on the website of the National Cancer Center Hospital (NCCH) in Japan.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirayama, T., Ikezawa, S., Okubo, R. et al. Mental health care use and related factors in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Support Care Cancer 31, 247 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07708-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07708-4