Abstract

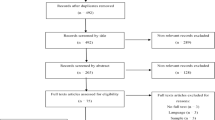

Physiological stress is thought to be one way that early adversity may impact children's health. How this occurs may be related to parental factors such as mothers’ own stress and parenting behaviour. Hair cortisol offers a novel method for examining long-term physiological stress in mother–child dyads. The current study used hair cortisol to examine the role that maternal physiological stress and parenting behaviours play in explaining any effects of adversity on young children’s physiological stress. This cross-sectional study comprised 603 mother–child dyads at child age 2 years, recruited during pregnancy for their experience of adversity through an Australian nurse home visiting trial. Hair cortisol data were available for 438 participating mothers (73%) and 319 (53%) children. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to define composite exposures of economic (e.g. unemployment, financial hardship) and psychosocial (e.g. poor mental health, family violence) adversity, and positive maternal parenting behaviour (e.g. warm, responsive). Structural equation modelling examined maternal mediating pathways through which adversity was associated with children’s physiological stress. Results of the structural model showed that higher maternal and child physiological stress (hair cortisol) were positively associated with one another. Parenting behaviour was not associated with children’s physiological stress. There was no evidence of any mediating pathways by which economic or psychosocial adversity were associated with children’s physiological stress. The independent association identified between maternal and child hair cortisol suggests that young children’s physiological stress may not be determined by exogenous environmental exposures; endogenous genetic factors may play a greater role.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bauer AM, Boyce WT (2004) Prophecies of childhood: how children's social environments and biological propensities affect the health of populations. Int J Behav Med 11(3):164–175. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1103_5

Goldfeld S, O'Connor M, Chong S et al (2018) The impact of multidimensional disadvantage over childhood on developmental outcomes in Australia. Int J Epidemiol 47(5):1485–1496. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy087

Evans GW, Kim P (2010) Multiple risk exposure as a potential explanatory mechanism for the socioeconomic status-health gradient. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186(1):174–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05336.x

Danese A, McEwen BS (2012) Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav 106(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019

Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child, and Family Health et al (2012) The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Gunnar MR, Donzella B (2002) Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 27(1–2):199–220

Gunnar MR, Quevedo K (2007) The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu Rev Psychol 58:145–173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605

Stalder T, Kirschbaum C (2012) Analysis of cortisol in hair—state of the art and future directions. Brain Behav Immun 26:1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.002

Vaghri Z, Guhn M, Weinberg J et al (2013) Hair cortisol reflects socio-economic factors and hair zinc in preschoolers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38(3):331–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.009

Windhorst DA, Rippe RC, Mileva-Seitz VR et al (2017) Mild perinatal adversities moderate the association between maternal harsh parenting and hair cortisol: evidence for differential susceptibility. Dev Psychobiol 59(3):324–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21497

Palmer FB, Anand KJ, Graff JC et al (2013) Early adversity, socioemotional development, and stress in urban 1-year-old children. J Pediatr 163(6):1733–1739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.030

Gray NA, Dhana A, Van Der Vyver L et al (2018) Determinants of hair cortisol concentration in children: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 87:204–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.10.022

Kao K, Doan SN, St John AM, Meyer JS, Tarullo AR (2018) Salivary cortisol reactivity in preschoolers is associated with hair cortisol and behavioral problems. Stress 21(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2017.1391210

Flom M, St John AM, Meyer JS, Tarullo AR (2017) Infant hair cortisol: associations with salivary cortisol and environmental context. Dev Psychobiol 59(1):26–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21449

Karlén J, Frostell A, Theodorsson E, Faresjö T, Ludvigsson J (2013) Maternal influence on child HPA axis: a prospective study of cortisol levels in hair. Pediatrics 132(5):e133–1340. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1178

Olstad DL, Ball K, Wright C et al (2016) Hair cortisol levels, perceived stress and body mass index in women and children living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods: the READI study. Stress 19(2):158–167. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2016.1160282

Liu CH, Fink G, Brentani H, Brentani A (2017) An assessment of hair cortisol among postpartum Brazilian mothers and infants from a high-risk community in São Paulo: intra-individual stability and association in mother–infant dyads. Dev Psychobiol 59(7):916–926. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21557

Ouellette SJ, Russell E, Kryski KR et al (2015) Hair cortisol concentrations in higher- and lower-stress mother–daughter dyads: a pilot study of associations and moderators. Dev Psychobiol 57(5):519–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21302

Halevi G, Djalovski A, Kanat-Maymon Y et al (2017) The social transmission of risk: maternal stress physiology, synchronous parenting, and well-being mediate the effects of war exposure on child psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 126(8):1087–1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000307

Kao K, Tuladhar CT, Meyer JS, Tarullo AR (2019) Emotion regulation moderates the association between parent and child hair cortisol concentrations. Dev Psychobiol. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21850(Epub ahead of print)

Conger KJ, Rueter MA, Conger RD (2000) The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: the family stress model. In: Crockett LJ, Silbereisen RK (eds) Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 201–223

Conger RD, Conger KJ (2002) Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. J Marriage Fam 64(2):361–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x

Neppl TK, Senia JM, Donnellan MB (2016) Effects of economic hardship: testing the family stress model over time. J Fam Psychol 30(1):12–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000168

Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J, Kohen DE (2002) Family processes as pathways from income to young children's development. Dev Psychol 32(5):719–794

Kiernan KE, Mensah F (2011) Poverty, family resources and children's early educational attainment: the mediating role of parenting. Br Educ Res J 37(2):317–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411921003596911

National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (2016) Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0–8. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/21868

Flouri E, Midouhas E, Joshi H, Tzavidis N (2015) Emotional and behavioural resilience to multiple risk exposure in early life: the role of parenting. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24(7):745–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0619-7

Simmons JG, Azpitarte F, Roost FD et al (2019) Correlates of hair cortisol concentrations in disadvantaged young children. Stress Health 35(1):104–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2842

Tarullo AR, St John AM, Meyer JS (2017) Chronic stress in the mother–infant dyad: maternal hair cortisol, infant salivary cortisol and interactional synchrony. Infant Behav Dev 47:92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.03.007

Goldfeld S, Price A, Bryson H et al (2017) 'right@home': A randomised controlled trial of sustained nurse home visiting from pregnancy to child age 2 years, versus usual care, to improve parent care, parent responsivity and the home learning environment at 2 years. BMJ Open 7(3):e013307. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013307

Price A, Bryson H, Mensah F et al (2018) A brief survey to identify pregnant women experiencing increased psychosocial and socioeconomic risk. Women and Birth. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.08.162(Epub ahead of print)

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation, Sydney

Henry JD, Crawford JR (2005) The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 44(2):227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

Zubrick SR, Lucas N, Westrupp EM, Nicholson JM (2014) Parenting measures in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children: construct validity and measurement quality, Waves 1 to 4. Department of Social Services, Canberra

Australian Institute of Family Studies Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/. Accessed 30 Nov 2017

Caldwell B, Bradley R (2003) Home observation for measurement of the environment: administration manual. Family & Human Dynamics Research Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe

Bryson HE, Goldfeld S, Price AMH, Mensah F (2019) Hair cortisol as a measure of the stress response to social adversity in young children. Dev Psychobiol 61(4):525–542. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21840

Dettenborn L, Muhtz C, Skoluda N et al (2012) Introducing a novel method to assess cumulative steroid concentrations: increased hair cortisol concentrations over 6 months in medicated patients with depression. Stress 15(3):348–353. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2011.619239

Wester VL, van der Wulp NRP, Koper JW, de Rijke YB, van Rossum EFC (2016) Hair cortisol and cortisone are decreased by natural sunlight. Psychoneuroendocrinology 72:94–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.06.016

Kirschbaum C, Tietze A, Skoluda N, Dettenborn L (2009) Hair as a retrospective calendar of cortisol production-increased cortisol incorporation into hair in the third trimester of pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(1):32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.024

Goldfeld S, Price A, Smith C et al (2019) Nurse home visiting for families experiencing adversity: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1206

Stalder T, Steudte-Schmiedgen S, Alexander N et al (2017) Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 77:261–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.017

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th edn. Guilford Publications, New York

Brown T (2006) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guildford, New York

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2017) Mplus User's Guide 8th Edition. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Tucker-Drob EM, Grotzinger AD, Briley DA et al (2017) Genetic influences on hormonal markers of chronic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function in human hair. Psychol Med 19:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003068

Rietschel L, Streit F, Zhu G et al (2017) Hair cortisol in twins: heritability and genetic overlap with psychological variables and stress-system genes. Sci Rep 7(1):15351. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11852-3

de Kloet ER (2008) About stress hormones and resilience to psychopathology. J Neuroendocrinol 20(6):885–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01707.x

Gidlow CJ, Randall J, Gillman J, Silk S, Jones MV (2016) Hair cortisol and self-reported stress in healthy, working adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63:163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.022

Abell JG, Stalder T, Ferrie JE et al (2016) Assessing cortisol from hair samples in a large observational cohort: the Whitehall II study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 73:148–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.07.214

Bennetts SK, Mensah FK, Green J et al (2017) Mothers’ experiences of parent-reported and video-recorded observational assessments. J Child Fam Stud 26(12):3312–3326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0826-1

Gridley N, Blower S, Dunn A et al (2019) Psychometric properties of parent-child (0–5 years) interaction outcome measures as used in randomized controlled trials of parent programs: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 22(2):253–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00275-3

Gomez R, Summers M, Summers A, Wolf A, Summers JJ (2014) Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: factor structure and test-retest invariance, and temporal stability and uniqueness of latent factors in older adults. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 36(2):308–317

Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B (2000) The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev 71(3):543–562

Kemper KJ, Kelleher KJ (1996) Family psychosocial screening: instruments and techniques. Ambul Child Health 4:325–339

Acknowledgements

The “right@home” sustained nurse home visiting trial is a research collaboration between the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY); the Translational Research and Social Innovation (TReSI) Group at Western Sydney University; and the Centre for Community Child Health (CCCH), which is a department of The Royal Children's Hospital and a research group of Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. We thank all families, the researchers, nurses and social care practitioners working on the right@home trial, the antenatal clinic staff at participating hospitals who helped facilitate the research, and the Expert Reference Group for their guidance in designing the trial.

Funding

“right@home” is funded by the Victorian Department of Education and Training, the Tasmanian Department of Health and Human Services, the Ian Potter Foundation, Sabemo Trust, Sidney Myer Fund, the Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation, and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, Project Grant 1079418). Research at the MCRI is supported by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. HB is supported by an MCRI Research Group Scholarship and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. SG is supported by NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship 1155290, FM by NHMRC Career Development Fellowship 1111160 and RG by NHMRC Career Development Fellowship 1109889. The funding sources had no involvement in the collection, analysis or decision to submit this article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bryson, H.E., Mensah, F., Goldfeld, S. et al. Hair cortisol in mother–child dyads: examining the roles of maternal parenting and stress in the context of early childhood adversity. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30, 563–577 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01537-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01537-0