Abstract

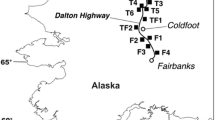

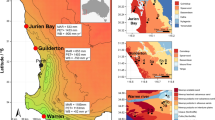

Phosphorus (P) availability in terrestrial ecosystems depends on soil age, climate, parent material, topographic position, and biota, but the relative importance of these drivers has not been assessed. To ask which factor has the strongest influence on long- and short-timescale metrics of P availability, we sampled soils across a full-factorial combination of two parent materials [quartz diorite (QD) and volcaniclastic (VC)], three topographic positions (ridge, slope, and valley), and across 550 m in elevation in 17 sub-watersheds of the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico. VC rocks had double the P content of QD (600 vs. 300 ppm; P < 0.0001), and soil P was similarly approximately 2× higher in VC-derived soils (P < 0.0001). Parent material also explained the most variance in our two other long-timescale metrics of P status: the fraction of recalcitrant P (56% variance explained) and the loss of P relative to parent material (35% variance explained), both of which were higher on VC-derived soils (P < 0.0001 for both). Topographic position explained an additional 10–15% of the variance in these metrics. In contrast, there was no parent material effect on the more labile NaHCO3- and NaOH-extractable P soil pools, which were approximately 2.5× greater in valleys than on ridges (P < 0.0001). Taken together, these data suggest that the relative importance of different state factors varies depending on the ecosystem property of interest and that parent material and topography can play sub-equal roles in driving differences in ecosystem P status across landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amundson R, Jenny H. 1997. Thinking of biology: on a state factor model of ecosystems. Bioscience 47(8):536–43.

Barone JA, Thomlinson J, Anglada-Cordero P, Zimmerman JK. 2008. Metacommunity structure of tropical forests along an elevational gradient in Puerto Rico. J Trop Ecol 24:1–10.

Bawiec WJ, Ed. 1999. Geology, geochemistry, geophysics, mineral occurrences and mineral resource assessment for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. US Geological Survey Open-File Report 98-038 (available online only).

Brimhall GH, Dietrich WE. 1987. Constitutive mass balance relations between chemical composition, volume, density, porosity, and strain in metasomatic hydrochemical systems: results on weathering and pedogenesis. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 51:567–87.

Brookshire ENJ, Gerber S, Webster JR, Vose JM, Swank WT. 2011. Direct effects of temperature on forest nitrogen cycling revealed through analysis of long-term watershed records. Glob Change Biol 17:297–308.

Buss HL, Mathur R, White AF, Brantley SL. 2010. Phosphorus and iron cycling in deep saprolite, Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico. Chem Geol 269:52–636.

Chacon N, Silver WL, Dubinsky EA, Cusack DF. 2006. Iron reduction and soil phosphorus solubilization in humid tropical forests soils: the roles of labile carbon pools and an electron shuttle compound. Biogeochemistry 78:67–84.

Chadwick OA, Derry LA, Vitousek PM, Huebert BJ, Hedin LO. 1999. Changing sources of nutrients during four million years of ecosystem development. Nature 397:491–7.

Chadwick OA, Gavenda, RT, Kelly EF, Ziegler K. 2003. The impact of climate on the biogeochemical functioning of volcanic soils. Chemical Geol 202:195–223.

Cleveland CC, Townsend AR, Taylor P, Alvarez-Clare S, Bustamante MMC, Chuyong G, Dobrowski SZ, Solomon Z, Grierson P, Harms KE, Houlton BZ, Marklein A, Partion W, Porder S, Reed SC, Sierra CA, Silver WL, Tanner EVJ, Edmund VJ, Wieder WR. 2011. Relationships among net primary productivity, nutrients climate in tropical rain forest: a pan-tropical analysis. Ecol Lett 14(9):939–47.

Crews TE, Kitayama K, Fownes JH, Riley RH, Herbert DA, Mueller-Dombois D, Vitousek PM. 1995. Changes in soil phosphorus ecosystem dynamics across a long chronosequence in Hawaii. Ecology 76(5):1407–24.

Cross AF, Schlesinger WH. 1995. A literature review and evaluation of the Hedley fractionation: applications to the biogeochemical cycle of soil phosphorus in natural ecosystems. Geoderma 64:197–214.

Davidson EA, Reis de Carvalho CJ, Figueira AM, Ishida FY, Ometto JPHB, Nardoto GB, Saba RT, Hayashi SN, Leal EC, Vieira ICG, Martinelli L. 2007. Recuperation of nitrogen cycling in Amazonian forests following agricultural abandonment. Nature 449:995–8.

De’ath G, Fabricius KE. 2000. Classification and regression trees: a powerful yet simple technique for ecological data analysis. Ecology 81:3178–92.

Dieter D, Elsenbeer H, Turner BL. 2010. Phosphorus fractionation in lowland tropical rainforest soils in central Panama. Catena 82(2):118–25.

Elser JJ, Bracken MES, Cleland EE, Gruner DS, Harpolse WS, Hillebrand H, Ngai JT, Seabloom EW, Shurin JB, Smith JE. 2007. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in fresh-water, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Lett 10:1135–42.

Frizano J, Johnson AH, Van DR, Scatena FN. 2002. Soil phosphorus fractionation during forest development on landslide scars in the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico. Biotropica 34(1):17–26.

Garcia-Montiel DC, Neill C, Melillo J, Suzanne T, Steudler PA, Cerri CC. 2000. Soil phosphorus transformations following forest clearing for pasture in the Brazilian Amazon. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64:1792–804.

Germer S, Neill C, Krusche AV, Elsenbeer H. 2010. Influence of land-use change on near-surface hydrological processes: undisturbed forest to pasture. J Hydrol 380(3–4):473–80.

Harrison AF. 1987. Soil organic phosphorus: a review of world literature. Wallingford: CAB International.

Hedley MJ, Stewart JWB, Chauhan BS. 1982. Changes in inorganic and organic soil phosphorus fractions by cultivation practices and by laboratory incubations. Soil Sci Soc Am J 46:970–6.

Huffaker, L. 2002. In: Brannon GR, Ragus GF, Eds. Soil survey of Caribbean National Forest and Luquillo Experimental Forest, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. United States Department of Agriculture and Natural Resource Conservation Service. 181 pp.

Jenny H. 1941. Factors of soil formation: a system of quantitative pedology. New York (NY): McGraw Hill.

Johnson AH, Frizano J, Vann DR. 2003. Biogeochemical implications of labile phosphorus in forest soils determine by the Hedley fractionation procedure. Oecologia 135(4):487–99.

Kitayama K, Majalap-Lee N, Aiba S. 2000. Soil phosphorus fractionation and phosphorus-use efficiencies of tropical rainforests along altitudinal gradients of Mount Kinabalu, Borneo. Oecologia 123(3):342–9.

Kurtz AC, Derry LA, Chadwick OA, Alfano MJ. 2000. Refractory element mobility in volcanic soils. Geology 28:683–6.

Larsen MC, Torres-Sanchez AJ. 1998. The frequency and distribution of recent landslides in three montane tropical regions of Puerto Rico. Geomorphology 24:309–31.

McGroddy ME, Daufresne T, Hedin LO. 2004. Scaling of C:N:P stoichiometry in forests worldwide: implications of terrestrial redfield-type ratios. Ecology 85(9):2390–401.

Miller AJ, Schuur EAG, Chadwick OA. 2001. Redox control of phosphorus pools in Hawaiian montane forest. Geoderma 102:219–37.

Pett-Ridge JC. 2009. Contributions of dust to phosphorus cycling in tropical forests of the Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico. Biogeochemistry 94:63–80.

Porder S, Payton A, Vitousek PM. 2005. Erosion landscape development affect plant nutrient status in the Hawaiian Islands. Oecologia 142:440–9.

Porder S, Hilley GE, Chadwick OA. 2007. Chemical weathering, mass loss, dust inputs across a climate by time matrix in the Hawaiian Islands. Earth Planet Sci Lett 258(3–4):414–27.

Porder S, Chadwick OA. 2009. Climate and soil-age constraints on nutrient uplift and retention by plants. Ecology 90(3):623–36.

Porder S, Ramachandran S. 2012. The phosphorus content of common rocks—a potential driver of ecosystem P status. Plant and Soil. doi:10.1007/s11104-012-1490-2.

Raich JW, Russell AE, Crews TE, Farrington H, Vitousek PM. 1996. Both nitrogen and phosphorus limit plant production on young Hawaiian lava flows. Biogeochemistry 32:1–14.

Reed SC, Vitousek PM, Cleveland CC. 2011. Are patterns in nutrient limitation belowground consistent with those aboveground: results from a 4 million year chronosequence. Biogeochemistry 106(3):323–36.

Reich PB, Oleksyn J. 2004. Global patterns of plant leaf N and P in relation to temperature and latitude. PNAS 101(30):11001–6.

Riebe CS, Kirchner JW, Finkel RC. 2003. Long-term rates of chemical weathering and physical erosion from cosmogenic nuclides and geochemical mass balance. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 67(22):4411–27.

Richter DD, Allen HL, Li J, Markewitz D, Raikes J. 2006. Bioavailability of slowly cycling soil phosphorus: major restructuring of soil P fractions over four decades in an aggrading forest. Oecologia 150:259–71.

Sanchez PA. 1976. Properties and management of soils in the tropics. New York: Wiley.

Scatena FN. 1989. An introduction to the physiography and history of the Bisley experimental watersheds in the Luquillo Mountains of Puerto Rico. US Forest Service General Technical Report.

Schuur EAG, Matson PA. 2001. Net primary productivity and nutrient cycling across a mesic to wet precipitation gradient in Hawaiian montane forest. Oecologia 128(3):431–42.

Selmants PC, Hart SC. 2008. Substrate age and tree islands influence carbon and nitrogen dynamics across a retrogressive semiarid chronosequence. Global Biogeochem Cycles 22:1–13.

Silver WL, Scatena FN, Johnson AH, Siccama TG, Sanchez MJ. 1994. Nutrient availability in a montane wet tropical forest: spatial patterns methodological considerations. Plant Soil 164(1):129–45.

Silver WL, Lugo AE, Keller M. 1999. Soil oxygen availability and biogeochemistry along rainfall and topographic gradients in upland wet tropical forest soils. Biogeochemistry 44:301–28.

Syers JK, Johnston AE, Curtin D. 2008. Reconciling changing concepts of soil phosphorus behaviour with agronomic information: efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use. Rome: FAO.

Takyu M, Aiba S, Kitayama K. 2002. Effects of topography on tropical lower montane forests under different geological conditions on Mount Kinabalu, Borneo. Plant Ecol 159:35–49.

Tiessen H, Moir JO. 1993. Characterization of available P by sequential extraction. Soil sampling methods of analysis. Canadian Society of Soil Science. Boca Raton: Lewis Publishers. pp. 75–86.

Townsend AR, Asner GP, Cleveland CC. 2008. The biogeochemical heterogeneity of tropical forests. Trends Ecol Evol 23(8):424–31.

Townsend AR, Cleveland CC, Houlton BZ, Alden CB, White JWC. 2011. Multi-element regulation of the tropical forest carbon cycle. Front Ecol Environ 9(1):9–17.

Turner BL, Haygarth PM. 2003. Changes in bicarbonate-extractable inorganic and organic phosphorus by drying pasture soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 67:344–50.

Turner BL, Engelbrecht BMJ. 2011. Soil organic phosphorus in lowland tropical rain forests. Biogeochemistry 103:297–315.

United States Department of Agriculture. 2002. Soil Survey of Caribbean National Forest and Luquillo Experimental Forest, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Vitousek PM. 1984. Litterfall, nutrient cycling, and nutrient limitation in tropical forests. Ecology 65:285–98.

Vitousek PM, Sanford RL Jr. 1986. Nutrient cycling in moist tropical forest. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 17:137–67.

Vitousek PM, Farrington H. 1997. Nutrient limitation and soil development: Experimental test of a biogeochemical theory. Biogeochemistry 37:63–75.

Vitousek PM, Chadwick O, Matson P, Allison S, Derry L, Kettley L, Luers A, Mecking E, Monastra V, Porder S. 2003. Erosion and the rejuvenation of weathering-derived nutrient supply in an old tropical landscape. Ecosystems 6:762–72.

Vitousek PM. 2004. Nutrient cycling and limitation: Hawai‘i as a model system. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

Walker TW, Syers JK. 1976. The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. Geoderma 15:1–19.

Wardle DA, Walker LR, Bardgett RD. 2004. Ecosystem properties and forest decline in contrasting long-term chronosequences. Science 305:509–13.

Weaver PL. 1991. Environmental gradients affect forest composition in the Luquillo Mountains of Puerto Rico. lnterciencia 16:142–51.

White AF, Blum AE, Schulz MS, Vivit DV, Stonestrom DA, Larsen M, Murphy SF, Eberl D. 1998. Chemical weathering in a tropical watershed, Luquillo mountains, Puerto Rico: I. Long- term versus short-term weathering fluxes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 62(2):209–26 (table headings).

Zarin DJ, Johnson AH. 1995. Nutrient accumulation during primary succession in a montane tropical forest, Puerto Rico. Soil Sci Soc Am J 59:1444–52.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Fred Scatena, Art Johnson, Miguel Leon, Hao Xing, John Clark, Zhuo Wang, Joanna Karaman, and Swee Lim for their expertise and assistance in the field. Laura Schreeg, Katie Amatangelo, Harmony Lu, Whendee Silver and two anonymous reviewers provided insightful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. This work was funded by the Andrew Mellon Foundation and NSF DEB 0918387 to SP, and NSF EAR 0722476 to the University of Pennsylvania.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Contributions

SP and SM conceived the study, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mage, S.M., Porder, S. Parent Material and Topography Determine Soil Phosphorus Status in the Luquillo Mountains of Puerto Rico. Ecosystems 16, 284–294 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9612-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9612-5