Abstract

The purpose of this study was to map the supervision of European trainees in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases during their training. An international cross-sectional questionnaire survey of 38 questions was distributed among trainees and recently graduated medical specialists from European countries. Descriptive analyses were performed on both the total group of respondents and regionally. In total, 393 respondents from 37 different countries were included. The median of overall satisfaction with the supervisor was 4 (interquartile range 3–4) on a Likert scale (range 1, not satisfied at all–5, completely satisfied). Overall, merely 34% of respondents received constructive feedback from their supervisor on a regularly basis, 36% could evaluate their own supervisor, and just 63% were evaluated on their skills using a written plan. Fifty-two percent did not receive the opportunity to do a part of the specialty training abroad and 63% received support from their supervisors to be involved in research projects or publishing papers. A considerable proportion of trainees, mainly in Southern and Eastern European regions, felt that they did not receive sufficient supervision. This information may be useful in the pursuit of harmonizing the quality of training, achieving a common curriculum, and identifying robust and objective criteria to coach and evaluate trainees in a proper way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinical microbiology (CM) and infectious diseases (ID) are two medical specialties with required expertise in diagnosis, management, prevention, and treatment of all types of infections [1]. Usually, both specialists work together to improve the outcome of patients with infections, both with an individual and public health perspectives. CM and ID are not equally recognized as medical specialties in all European countries, which makes it more difficult to strive after and achieve a common European curriculum [2]. Achieving uniformity in knowledge and skills of trainees in CM and ID has proven to be difficult due to intrinsic differences of the curricula between countries [3].

The UEMS (Union Européenne des Médecins Spécialistes) is a non-governmental organization representing national associations of medical specialties at the European level. A common curriculum in CM was recently developed by UEMS section Medical Microbiology, while the ID section is planning the same, both with input of many national medical associations to increase the possibility of free movement of trainees and medical CM/ID specialists within Europe [4]. As part of this development, it is important to acquire insight into how trainees are supervised and evaluated in different countries, as it may help to establish common criteria that could be accepted and adopted in the different national curricula taking into account the different settings.

Unfortunately, there is only limited information about how young CM and ID trainees perceive supervision in clinical and laboratory settings and who contributes to the different aspects of education of trainees. Supervision has been defined as the provision of monitoring, guidance, and feedback on matters of personal, professional, and educational development in the context of the doctor’s care of patients [5]. The final aim is to improve patients’ care, for which good quality of supervision is necessary [6]. Maintaining a high quality represents a clinical challenge for the medical profession and must be a priority for the health system. Effective supervision builds medical professionalism, improving patients’ safety and outcomes, and acquisition of skills by trainees [7].

The aim of this international cross-sectional questionnaire survey was to map the situation of how CM and ID trainees are supervised during their training, how satisfied trainees are regarding the supervision they receive, and to assess the differences in supervision habits between European countries.

Methods

Study design

The questionnaire was prepared by the steering committee of the Trainee Association of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (TAE) to investigate the current status of supervision among European trainees during their training. A pilot phase involving 36 participants from different countries (Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey) was performed in order to assess the feasibility of the questionnaire and to allow for amendments. The final questionnaire was made available online between 1 June and 30 September 2017 using the SoSci Survey platform, which is a free open source professional software made in Germany (www.socscisurvey.de).

Whereas no specific inclusion criteria were applied, participants who did not answer all questions were excluded for this analysis. The aim was to reach as many trainees and young medical CM and ID specialists (i.e., < 3 years after training completion) as possible in order to have a reliable overview of the actual conditions of supervision in Europe. The web link of the questionnaire was distributed by e-mail among trainees in Europe using the TAE network including representatives of both CM and ID national societies from 37 out of 58 eligible European countries. The survey was also promoted by the ESCMID and the TAE in their newsletters and on the ESCMID and TAE websites, potentially reaching more than 10,000 members. The participation of non-European young medical specialists and trainees was allowed due to the international profile of ESCMID and TAE, but results were analyzed as a separate group. Before starting to fill in the questionnaire, each responder was informed about the purpose and anonymity of the survey. No financial or other incentive was provided for the respondents. The complete questionnaire is provided as supplementary material, Table 1. Ethical approval was not required in this case due to volunteering of participants.

Definitions and questionnaire domains

The questionnaire included 20 demographic questions and 18 specific questions on supervision. Overall, there were 12 yes/no questions, 8 multiple-choice questions, 7 numeric questions, and 11 Likert scale self-assessment questions (supplementary material, Table 1). A supervisor was defined as “a superior member of staff holding the same medical specialty as the intended one of the trainee.” The supervisor is directly and officially concerned with the progress and evaluation of the trainee in the department (or specific rotation) where the trainee is working, and has the responsibility for him/her. A young medical specialist was defined as a physician who finished the specialty no more than 3 years ago. European countries were categorized into five geographical regions as proposed by the ESCMID Parity Commission (see supplementary material, Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

The results were collected using SoSci Survey version 2.5.00-i. Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median/IQR depending on the distribution. Differences between the regions were investigated using chi-square or Fisher’s tests as appropriate for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Demographic characteristics

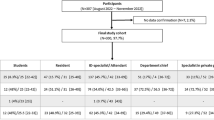

After exclusion of 172 fully incomplete questionnaires, data from 393 participants were analyzed. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of these respondents, coming from 37 countries. The mean age was 34 years (SD ± 7 years). Most respondents worked in Spain (n = 60, 15.3%), Italy (n = 40, 10.2%), The Netherlands (n = 40, 10.2%), Turkey (n = 35, 8.9%), and the UK (n = 30, 7.6%) (Fig. 1). Thirty-one percent of participants worked in countries which belong to Western Europe (n = 123), 14% Northern (n = 55), 7.6% Eastern (n = 30), 27.7% Southwestern (n = 109), 16.5% Southeastern (n = 65), and 2.8% other countries (n = 11). There were 265 trainees (67.4%) and 128 recently finished medical specialists (32.6%), with a CM:ID ratio of 1 to 1.14 for trainees and 1 to 1.41 for medical specialists, respectively.

Distribution of participants according to their country of work. Other countries include those colored as purple plus: the USA (n = 2, 0.5%), Kenya (n = 1, 0.2%), Brazil (n = 1, 0.2%), Algeria (n = 1, 0.2%), Morocco (n = 1, 0.2%), Mozambique (n = 1, 0.2%), Nigeria (n = 1, 0.2%), and Peru (n = 1, 0.2%)

Supervision

Table 2 presents supervisor characteristics in the different regions of Europe. Among respondents, the median number of supervisors was 1, interquartile range (IQR) 1–2, per week. In a Likert scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (completely satisfied), the median of satisfaction with supervisors was 4 (IQR 3–4). Around 60% (229/390) of respondents declared that their supervisor had a superior or colleague of the same level allowing them to get a second opinion about their way of working, and 64% (251/390) stated that they could speak with another superior about difficulties with the supervisor. Nearly 50% (194/390) of the respondents stated that their supervisors had to report to (other) senior staff about the training improvements, and 36% (141/390) of trainees could evaluate their own supervisor.

In a Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), the median of receiving sufficient supervision was 4 (IQR 2–4) according to respondents. The survey evaluated in 8 Likert scale questions how the supervisor contributed to the education in specialty training (1 being never and 5 very often): in 78% (303/390), the supervisor was often or very often available for urgent questions; 54% (209/389) confirmed that the supervisor was available for hand-on help often or very often; 42% (163/387) said that the supervisor never or rarely provided them with updates in the fields of CM or ID; 49% (192/389) stated that their supervisor never or rarely took the initiative to schedule individual meetings with trainees; 40% (154/389) perceived that the supervisor often or very often contributed to the educational part of training; only 34% (186/389) receive constructive feedback from their supervisor often or very often; 50% (83/389) stated that they often or very often learn diagnostic and therapeutic management skills by observing how their supervisor works; and 37% (143/389) of trainees were never evaluated on their skills using a written plan.

Three questions explored if the supervisor was supporting the trainees’ career regarding the possibilities for congress visits, experience outside the main institute, and exposure to scientific activities. Sixty-three percent (247/389) of respondents received the possibility to attend a congress or extra courses. About half of respondents, 52% (201/388), did not have the opportunity to do part of the specialty training or some extra rotations abroad or in an institute not associated with the main education institute. Finally, 63% (245/387) of respondents received support from their supervisors to be involved in research projects and/or publishing papers.

Discussion

We found notable differences in supervision of trainees among the different European regions. Trainees in Western and Northern regions were more satisfied. Furthermore, the possibility to evaluate supervisors and to do rotations abroad is scarce in all regions.

In our study, most respondents were female (62%) with an average age of 34 years. Most of them were married (39%) or single (24%) and had a median of two children. Interestingly, these characteristics reflect social changes in the medical community, which is different to previous times where males represented the vast majority of physicians [8, 9].

Of note, ID was not recognized as a medical specialty in most of the Southwestern countries (majority of respondents came from Spain), whereas for CM, this was the case for mostly the Southeastern countries. Notably, there was no significant difference between European regions regarding the availability of written plans for the entire training period, as such plans were missing in substantial proportions in all regions. This underlines the need and explains the effort and interest of UEMS and ESCMID in creating a common plan and curriculum with the aim to harmonize training curricula to improve the quality of training [2].

According to our data, the workload acceptance was higher in Northern countries. A workload perceived as excessive might lead to burnout, as found in our previous survey about personal life and working conditions of trainees [10]. Preventive and therapeutic measures to avoid burnout syndrome among trainees are needed and some possible solutions may lie in the improved distribution of time and tasks [10]. At the same time, one third of the respondents do more than 20 h of extra work per month. These findings are comparable to those found in other studies [11]. Physicians including trainees play a crucial role in ensuring the functioning of hospitals; therefore, it is crucial not to exceed their work time too much. Consequently, some countries have already limited the maximum working hours of trainees [12].

Trainees usually have one supervisor per week and two thirds of them may count on a supervisor’s superior or colleague for a second opinion about their work in cases of disagreement (64%). In Western European countries, trainees can receive second opinions more frequently than in other countries (76%). Only 36% of respondents can evaluate their supervisor, which is surprisingly low and applies to all regions. In 2017, a study in the UK including 173,652 participants identified that appropriate workload, good supervision practice, and receipt of good quality feedback are key factors for trainee’ satisfaction [13]. Interestingly, our study showed that only 66% received feedback “sometimes, often, or very often” from their supervisors. Also, according to most respondents, the supervisor contributed only “sometimes” (IQR “rarely” to “often”) to the trainee’s education. This result may also reflect the lack of time and human resources as reported previously [14].

Three survey questions explored specifically whether the supervisor pushes the trainee’s career by helping on planning external rotations, attending extra courses, or supporting the involvement in research projects. The supervisor’s support in pushing the trainee’s career was even lower in our current survey in comparison to that of our previously reported study (lack of possibility of doing external rotation 48% versus 31% respectively) [3]. It is remarkable that in Western, Northern and Southwestern regions, supervisors offer more opportunities to follow extra courses, to attend congresses, and to do external rotations compared to other parts of Europe. It is important to state that up to 37% of respondents did not receive support for publishing papers or carrying out research projects, which was highest in the Eastern region (48%). In our opinion, trainees should be offered the possibility of at least a certain period of time for research during the mandatory training period.

The strength of this exploratory survey is that it included many countries and offered an overview of the current situation of supervision of CM and ID trainees. However, limitation is that the survey respondents may not be entirely representative of all trainees in Europe given the relatively small numbers of respondents in some countries, and it was not possible to calculate response rates because for many countries, we do not have information regarding the total number of trainees. Furthermore, a significant proportion of respondents who started the questionnaire did not complete the survey.

In conclusion, this exploratory survey gives an insight into the current supervision conditions for European trainees in CM and ID. Although there are many differences between European regions, a significant proportion of trainees feel that they do not receive sufficient supervision. The supervisor is not as available or accessible as should be. In order to improve the quality of training across different countries, it is important to increase the amount of constructive feedback provided by supervisors, create opportunities for trainees to receive a part of their training outside the main institute, ensure that there is a clear written plan for the specialty training, and provide the availability of another supervisor or superior who is independent and approachable in case there are difficulties between the trainee and the supervisor.

References

abms.org (2017) ABMS guide to medical specialties. American Board of Medical Specialties, Chicago Access 1st January 2018. Available on: http://www.abms.org

Read RC, Cornaglia G, Kahlmeter G et al (2011 May) Professional challenges and opportunities in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 11(5):408–415

Yusuf E, Ong DS, Martín-Quirós A et al (2017) A large survey among European trainees in clinical microbiology and infectious disease on training systems and training adequacy: identifying the gaps and suggesting improvements. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36(2):233–242

UEMS.es, European Union of Medical Specialists. Brussels, access 1st January 2018. Available on: https://www.uems.eu/about-us/medical-specialties

Kilminster SM, Jolly BC (2000) Effective supervision in clinical practice settings. Med Educ 34(10):827–840

McKee M, Black N (1992) Does the current use of juniors doctors in the United Kingdom affect the quality of medical care? Soc Sci Med 34(5):549–558

Forsyth KD (2009) Critical importance of effective supervision in postgraduate medical education. Med J Aust 191(4):196–197

Reichenbach L, Brown H (2004) Gender and academic medicine: impacts on the health workforce. BMJ 329(7469):792–795

Allen I (2005) Women doctors and their careers: what now? BMJ 331(7516):569–572

Maraolo AE, Ong DS, Cortes J et al (2017) Personal life and working conditions of trainees and young specialists in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Europe: a questionnaire survey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36:1287–1295

Tsai YH, Huang N, Chien LY et al (2016) Work hours and turnover intention among hospital physicians in Taiwan: does income matter? BMC Health Serv Res 16:667

Woodrow SI, Segouin C, Armbruster J et al (2006) Duty hours reforms in the United States, France, and Canada: is it time to refocus our attention on education? Acad Med 81:1045–1051

Gregory S, Demartini C (2017) Satisfaction of doctors with their training: evidence from UK. BMC Health Serv Res 17:851

Dickstein Y, Nir-Paz R, Pulcini C et al (2016 Sep) Staffing for infectious diseases, clinical microbiology and infection control in hospitals in 2015: results of an ESCMID member survey. Clin Microbiol Infect 22(9):812.e9–812.e17

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank our colleague trainees and young medical specialists for participating in this survey, and Maximilian Schwarz (Dipl. Psych.) from Marburg for his technical support on the online survey platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The Trainee Association of the ESCMID steering committee (TAE SC) members (ZPB, TCZ, DO, AEM, CR, and CC) designed the study. MS, JRB, and CP supervised the study. The TAE SC members acquired the data. ZPB and TCZ analyzed the data. ZPB, TCZ, and DO drafted the paper. All authors interpreted the data. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Before starting to fill in the questionnaire, each responder was informed about the purpose and anonymity of the survey. No financial or other incentive was provided for the respondents. Ethical approval was not required in this case due to volunteering of participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 1105 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Palacios-Baena, Z.R., Zapf, T.C., Ong, D.S.Y. et al. How are trainees in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases supervised in Europe? An international cross-sectional questionnaire survey by the Trainee Association of ESCMID. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37, 2381–2387 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3386-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3386-4