Abstract

The past is not in the classroom to observe and study. Thus, creating a lively and understandable image of a past period or situation is an achievement to be learned. A variety of tasks can be used to stimulate students to create an image of the past. In this experimental study, 151 grade 9 students (14–16 years old) participated by completing a drawing task or a writing task on the Roman Forum in Ancient Rome. Their products were compared. Additionally, the students’ perceptions of the tasks were explored by means of a questionnaire and an interview. The findings show that the written products contained more information elements than the drawings. However, in terms of the historical plausibility of the product, the drawn products and written products were comparable. Students who made a drawing reported higher situational interest than students who wrote a text.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historical understanding is an important aim of history education (Husbands 1996; Lee and Ashby 2000). Historical understanding has been conceptualized in terms of substantive knowledge (the contents of history, such as historical persons and situations) and procedural knowledge (the tools of history as a discipline, for example, change and continuity, cause and effect) (Lee and Ashby 2000; Lévesque 2008). An important part of substantive knowledge is knowledge of the physical and mental aspects of life in the past. Dawson (2009) formulated a set of guiding questions that can be used to enhance students’ “sense of period,” such as what would you have seen, what did people wear, in what kind of houses did they live, how did people travel and what attitudes and ideas did they have? Students need to create a concrete and vivid image of life in the past that is based on historical evidence (Lévesque 2008; Husbands 1996). Scholars in the field of history education have suggested a variety of approaches to support this historical imagination, such as the use of visual sources (e.g., paintings or photographs), historical films, and role-taking exercises (e.g., Cunningham 2009; Prangsma et al. 2009; Marcus et al. 2010). In a previous study, we explored the learning processes and outcomes of writing tasks in which students had to produce an image of a historical situation in a written product. In this contribution, we focus on the potential benefits of a drawing activity.

Especially in the science domain, considerable research has examined the use of drawing as a learning activity. By creating visual representations (i.e., using drawing tasks), students form an image of the topic they are studying. Most studies have focused on students drawing a phenomenon that is difficult to observe in the classroom, such as plate tectonics (Gobert and Clement 1999) or the planet Earth (Ehrlén 2008). Students create drawings to visualize such topics, displaying the mental model they have constructed while reading about them. This learning strategy can be used to enhance the understanding of abstract concepts (Van Meter and Firetto 2013). Schmidgall et al. (2018) describe three important components of such drawing activities: generation, visualization, and externalization. By drawing, students enter a generative learning process, make a transfer from text to picture by means of visualization, and externalize their mental representations in the form of a learner-generated drawing.

In the history domain, as in science, most of the topics studied are not directly observable. Situations and people from the past are gone, so they must be “re-constructed” using the historical evidence we do have, such as written sources and pictures (Lévesque 2008). Prangsma et al. (2009) have shown that reconstructions of historical phenomena can be stimulated by means of abstract drawings, such as cause and effect schemes or an illustrated timeline. However, when we want students to construct an image of the physical aspects of life in a particular period and place, representational drawings seem to be a more obvious choice. Representational drawings offer an as accurate as possible reflection of reality (Van Meter and Garner 2005; Van Meter and Firetto 2013). The potential of learner-generated representational drawing in history has not been previously investigated.

The aim of this study is to explore the images of the past that students produce as a result of a drawing task, compared with the images students display as a result of a writing task, which is a more commonly used type of task in secondary history education.

We will first address the potential benefits of learner-generated drawings for (history) education. We will then discuss aspects of the evaluation of these drawings.

Visualization and drawing in (history) education

In this section, we will focus on the possible benefits of visualization and drawing, i.e., making the invisible concrete, especially in history education.

Imagining the past can be very difficult because the past cannot be observed directly. Additionally, the past is often presented in education in terms of long-term developments, for example, Industrialization or the Cold War. However, when teaching about historical phenomena, it is considered beneficial to present topics in a concrete way, because then students will be better able to understand them (Prangsma et al. 2009; Husbands 1996). Research in the field of reading education confirms that concrete examples in a text stimulate students’ reading comprehension (De Koning and Van der Schoot 2013; Bos 2016; Boerma et al. 2016). Stein and Power (1996) propose that drawing tasks stimulate students to make what they have read concrete, and when students create concrete examples, they are “forced to think” (Stein and Power 1996, p. 66).

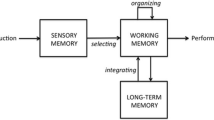

Moreover, drawing is considered a means of stimulating deep processing in various ways (Van Meter and Garner 2005). Students must consider which information they will include in their drawings, and they must organize information from the text. Then they transform that information into an image, connecting verbal and visual knowledge representations (Van Meter and Firetto 2013), as Schmidgall et al. (2018) also demonstrate. This process is in line with dual-coding theory (Sadoski and Paivio 2013), which states that processing both verbal and visual stimuli is a huge challenge for the brain. Processing information both verbally and visually results in more retrieval cues.

Drawing is a form of visualization. Although Bos (2016) views visualization as a “mental leap into imagined worlds,” this does not mean that visualization equals fantasy. Visualization stimulates students to make connections between new information and prior knowledge (Van Meter and Firetto 2013; Dilek 2010), which can be obtained within a school context or outside school, e.g., at home, from peers, or from media (Bronkhorst and Akkerman 2016). In history education, as Wineburg (2001) notes, this can be a challenge: students may be tempted to use anachronisms and presentism (applying items or ideas from the present to the past) (Cf., e.g., Dilek 2010; Huijgen et al. 2014; Wilschut 2012).

Few scholars discussed or studied the possible applications of drawing in history education. Prangsma et al. (2009) have explored how making timelines with pictures helps students grasp historical developments. Students who integrated pictures into a timeline achieved better learning results than students who created textual representations. Fournier and Wineberg (1997) used students’ drawings to explore how students picture the past with regard to gender issues. Levstik and Barton (2015) argue that creating a picture is a form of problem-solving because students must make numerous decisions before creating their final product. This was also stressed by Dilek (2010), who showed that drawing is an activity through which students can show their historical thinking skills. Additionally, Epstein (1994) suggests that students can relate more to the experiences of humans from the past through artwork (paintings and poetry) than through written essay-like tasks.

Learner-generated historical images

Various tasks can be used to prompt students to produce an image of the past. Findings from a previous study (De Leur et al. 2017) suggest that a writing task aiming for historical empathy results in different images than writing a summary. In this study, students were asked to write a short text on a historical event as if they themselves had been present, or through the eyes of a fictional historical character, or summarizing the event. The students who completed the task in one of the empathy conditions produced more rich historical images, in terms of the amount of information drawn from prior knowledge and imagination than the students who wrote a summary. However, the students who wrote a summary reproduced more information and included multiple perspectives. In other words, the type of task seems to matter (De Leur et al. 2017).

When using tasks in which students construct a historical image, an important question is how to assess the quality of this image. Visual representations are a way of expressing knowledge (Lohse et al. 1994), and in terms of drawing style, it is possible to discern between photo-realistic and schematic/iconic drawings (or elements within a drawing) (Van Leeuwen and Jewitt 2002). “Photo-realistic” means the student has drawn as realistically as possible; “schematic/iconic” means the student has used symbols or schematic sketches to represent an object or event. Drawings in both categories can be of equally high quality: one is not “better” than the other (Lohse et al. 1994). Another way of evaluating drawings is by their accuracy, as proposed by Van Meter and Garner (2005): “the degree to which completed drawings resemble the represented object(s)” (p. 299). In this case, accuracy does not take into account the drawing’s technical qualities in the sense of whether the drawing is beautiful. Based on a literature review, Van Meter and Garner (2005) consider the accuracy of a drawing to be a product of comprehension. When a drawing is accurate, the student understands the topic. However, they state that this can only be said of tasks with relatively simple content. Schwamborn et al. (2010) also associate drawing accuracy with comprehension.

In history education, there are some examples of assessment of drawings, and these focus mainly on the drawing’s historical accuracy. Historical accuracy is relevant, because the aim of the drawing is a reconstruction of the past that is grounded in historical evidence. To be historically accurate, drawings should be historically sound and historically bound, according to Dilek (2010) and Levstik and Barton (2015). By historically sound, they mean that evidence was used and that there are no obvious inaccuracies in the drawing. To create a historical image, prior knowledge (when applied correctly) or imagination can also be helpful (Lévesque 2008; De Leur et al. 2017). Historically bound refers to the historical plausibility of the drawing: the drawing must be credible from a historian’s point of view.

Drawing in the classroom: teachers and students

For teachers, drawing tasks provide an opportunity to see what is in their students’ mind’s eye (Epstein 1994). However, drawings cannot be regarded as exact copies of children’s conceptions. Children give meaning to their own drawings, and similar drawings can hold different meanings for the students who drew them. Students can mean more than they can (technically) draw, and similarly, drawings resembling one another can mean different things (Ehrlén 2008). Drawings are not only a source of information for teachers but can also be a tool to enhance further learning. For example, drawings can start a discussion, e.g., when students are asked to explain their drawings to one another (Ainsworth et al. 2011). In the case of history education, Levstik and Barton (2015) argue that drawings can be a starting point for future learning because during the drawing process students are confronted with the gaps in their historical knowledge, especially when they do not know what to draw. When explaining their drawings, students have the opportunity to correct their misconceptions or ask the teacher for help.

Epstein (1994) mentions an additional advantage of using artwork in the classroom for teachers: they can sometimes see students excel who had not done so previously. Moreover, individual differences in preferences for processing verbal or visual information are recognized (Childers et al. 1985; Cox 1999). In terms of processing information, some students prefer to work with words, some with images (e.g., Mayer and Massa 2003; Plass et al. 1998). Epstein (1994) suggests that students who prefer to work with images can show what they know when they are given the chance to work on a drawing task. Moreover, Van Meter and Garner (2005) propose that drawing can stimulate students’ affective processes, possibly resulting in increased interest or pleasure. Additionally, Epstein (1994) suggests that drawing can be an activity that provokes students’ interest.

Although drawing is a natural way for young children to express themselves, when they grow older and begin their formal education, they soon learn that writing is more valued than drawing. Children at school are extensively taught to express their thoughts and ideas in text, not in visual work (Anning 1999). Therefore, both students and teachers can be reluctant to use drawing as a learning activity. Teachers may feel unequipped to support their students or fear problems with classroom management during drawing tasks (Levstik and Barton 2015). Students, on the other hand, may fear drawing activities because they want to “get it right” (Levstik and Barton 2015), but are afraid they cannot draw well enough (Anning 1999), or may perceive drawing as difficult (Schmidgall et al. 2018).

In summary, studies have suggested that prompting students to work with learner-generated images could benefit learning. Based on the literature, we can assume that drawing can contribute to the processing of information, the activation of prior knowledge, and the production of a concrete image. Additionally, students’ preference for verbal or visual approaches may affect the accuracy of the image that is produced and students’ interest.

Research questions

The following research questions are addressed in this study:

- 1.

What is the effect of the type of task (drawing or writing) on the information that students include in their product, the historical plausibility of the image they construct, and the interest provoked by the task?

- 2.

What is the effect of the style of processing preference on the historical plausibility of the images students construct and the interest provoked by the task?

Method

To answer our research questions, we conducted an experimental study, with a drawing task and a writing task regarding the Roman Forum in 200 AD.

Participants and design

In this study, six grade 9 classes participated (N = 151, 14–16 years old). These classes came from four different schools, one in the north of the Netherlands and three in the west. All the schools were located in smaller cities and served students from both the city and the region. Four classes were HAVO (higher general secondary education) classes, whose students were preparing to enter a university of applied sciences. Two classes were VWO classes (the pre-university level). The students were familiar with the topic of Ancient Rome, which, as is customary in the Dutch curriculum and confirmed by the teachers of the participating classes, was taught approximately 18 months before the study. All the students voluntarily agreed to participate, with parental consent, after being informed about the research. We followed the guidelines of the UvA Ethical Board (approval nr. 1016-CDE-6911).

Within each class, students were randomly assigned to the drawing or writing condition, so that half of the students received the drawing task and half received the writing task. Students were not allowed to choose or to switch tasks. The participants in the two conditions were comparable in terms of gender (drawing, 51% male; writing, 49% male), age (drawing mean, 14.81; writing mean, 14.67), country of birth (drawing, 97% born in the Netherlands; writing, 100% born in the Netherlands), and mother tongue (drawing, 86% Dutch; writing. 82% Dutch).

Materials and learning task

The topic of our task was the Roman Forum. The aim of the task was to encourage the students to produce a rich image of the Roman Forum in 200 AD. All the students were given the same set of information to work with, which consisted of both text (509 words) and images (see Appendix). This information included a short introduction to the Roman Empire, to remind the students of what they had been taught earlier, a 3D map of the Roman Forum, a drawing of a Roman street, a description of the Roman Forum, a quotation from a play by Plautus about the people in the Forum, and a schedule of an average day for a Roman citizen. In the history textbooks that the students work with during history lessons, written sources and images are usually presented alongside each other. Thus, we stayed as close as possible to the tasks to which the students were accustomed. In addition, visual and verbal information can complement each other by creating rich mental images (Sadoski and Paivio 2013).

All the students were given the same assignment: “Imagine you are in the Roman Forum in 200 AD. What do you see?” Students in the drawing condition were asked to draw what they observed, and students in the writing condition had to write down their answers. The students were allowed 20 min to read the materials and then to write or draw and were encouraged to use all of that time. All students worked individually and in silence.

Before turning to our participants, we piloted the task in an urban class in Amsterdam at the VWO (pre-academic) level. In particular, we were examining the comprehensibility of the given information and whether students preferred blank paper to draw on or paper with a frame printed on it. As they chose the latter, in the experiments, we gave the students in the drawing condition a piece of paper with a small frame already printed on it. We did not alter the task itself as the pilot students indicated that it was clear and doable. Additionally, we interviewed two students to test our interview protocol, which proved satisfactory.

Measures

Prior knowledge pretest

To explore the students’ prior knowledge and associations, we used free recall answers to the following prompts: “what I know about life in Ancient Rome” and “what I see before me when I think of life in Ancient Rome.” These prompts were based on the word web instrument developed by Savenije et al. (2014) and inspired by Dawson’s (2009) questions related to physical aspects of life in the past. The students could use up to 10 min to write down as much as they knew.

Two teachers working in constant consultation with one another counted how many (correct) answers the students gave for the prompts. The total number of correct answers was used as the students’ prior knowledge score. An example of a correct answer is “there was slavery,” and an example of an incorrect one is “there were castles and knights.” A third rater (the first author) scored the items on a set of 15 randomly chosen tests (10%). The interrater correlation was Pearson’s r = .89.

Verbalizer/visualizer test

To explore the extent to which the participants preferred to work with verbal or visual information, we used the Style of Processing Scale (SOP scale) proposed by Childers et al. (1985). This scale does not measure ability or competence, only preference.

The test consisted of 22 items, scored on a four-point Likert scale (always true, usually true, usually false, always false). Examples of the items are “I do a lot of reading,” “I like to doodle,” and “My thinking often consists of mental ‘pictures’ or images.” Students score each item on a scale of 1 (always true) to 4 (always false). By reversing the items about drawing, the analysis leads to a total score for each student that ranges from a mainly verbal preference (total score close to 1) to a mainly visual preference (total score close to 4). Thus, the higher the score on the SOP scale, the higher the students’ visual preference (for the full Style of Processing Scale, see Childers et al. 1985). The Cronbach’s alpha was .69 (N = 131). To explore the effect of the style of processing preference, we divided the students in our sample into two groups. A total of 72.5% (N = 95) of the students scored lower than 2.5 on the four-point SOP scale and were classified in this study as having a verbal preference. A total of 27.5% (N = 36) of the students had a score of 2.5 or higher and were classified as having a visual preference.

Situational interest questionnaire

The students completed a situational interest questionnaire (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. 2010) that measured the interest evoked by the task they had completed. This questionnaire consisted of 12 statements in which students were asked whether they considered the task enjoyable and engaging (e.g., “the task we just completed was fascinating”) and important and valuable (e.g., “I think that what I learned from working on this is useful”). The students had to rate these statements on a 6-point Likert scale. The Cronbach’s alpha was .94 (N = 145).

Questionnaire and interviews on students’ perceptions

To gather information regarding how the students perceived the process and to explore the meaning the students themselves gave to their products, all the students completed a questionnaire on the task they just finished. This questionnaire consisted of five statements answered with yes or no, and the opportunity to add an explanation of the answer. Examples of statements were “I used the written text from the information leaflet” and “I think I would have liked the other task better.” We used the answers on this questionnaire as input for the interview protocol. Then, we conducted post-task semi-structured stimulated recall interviews, with 16 randomly chosen students from four classes; eight students who completed the drawing task and eight who completed the writing task. In total, we interviewed eight dyads. We chose to interview the students in dyads because it is believed that students are willing to talk more readily in pairs than when they are interviewed alone (Bosschaart et al. 2014; De Leur et al. 2015). Because the students were interviewed in dyads of one student from the writing condition and one student from the drawing condition, they could compare their experiences and comment on each other’s products during the interview. The students had their written product or drawing in front of them and answered prompts such as “How did you handle the task?” “Were there moments when you did not know how to proceed; if so, what did you do then?” and “What do you think you could have learned from this task?”

Analysis of drawings and written accounts

First, we coded the drawings according to their style: photo-realistic or schematic/iconic (cf. Lohse et al. 1994) (see Table 1). Photo-realistic drawings are as realistic as possible (real humans, buildings, etc.). In schematic drawings, iconic images are used, such as stick figures instead of clothed humans.

Then, we coded both the drawings and the written products based on the elements of historical accuracy according to Dilek (2010): information and historical plausibility (see Table 2). We started with reproduced information, which refers to how much of the given information was (verbatim) copied by the students. For this category, we used the following codes: none or one element, two elements and three or more elements. For example, the given information included the phrase “there were rich and poor Romans.” When a student wrote “I can see rich and poor people,” we coded it as reproduction. Reproduction could also be seen in the drawings. For example, the given information includes the phrase “a trip to one of the bathing houses.” When a student drew a building with the heading “bath house,” we coded it as reproduction. We proceeded with the information elements the students added to their products that were not literally in the sources but were derived from prior knowledge or from imagination. We coded this additional information the same way, i.e., none or one element, two elements, and three or more elements. Examples of additional information that appeared in both the drawings and the written products include slaves, a soldier on a horse, or a palanquin. A second rater scored a set of 25 randomly chosen products (17%) consisting of both drawings and writings. Cohen’s kappa was .81 for reproduced information and .87 for additional information, which is considered almost perfect (Landis and Koch 1977).

Finally, we assessed the drawings and written products in terms of the historical plausibility of the student’s image of the forum according to Dileks’s (2010) description of products being historically bound, i.e., credible from a historians’ point of view. We scored the products on three levels: 1 = basic, 2 = intermediate, and 3 = advanced. We labeled products as basic when the displayed image of the forum was poor, a-historic, or consisted of only minimal reproduction of the given sources. Products in which the displayed image of the forum may have been historically correct, which included a sufficient amount of information from the given sources or from prior knowledge to construct an acceptable image, were labeled intermediate. We used the “advanced” label for products in which the displayed image of the forum contained buildings, humans, and human (inter)actions, and consisted of information from the given sources and (correct) prior knowledge. Two teachers working in constant consultation assessed the drawings and the written products and together established a single score for historical plausibility. A third rater then scored a set of 33 randomly chosen products (21%) consisting of both drawings and writings. Cohen’s kappa was .78 which is considered substantial (Landis and Koch 1977).

Procedure

This experimental study was conducted during the students’ regular history classes. First, we asked the students to complete the pretest on the Ancient Romans to explore their prior (associative) knowledge. Next, they filled out the verbalizer/visualizer questionnaire (Childers et al. 1985) which measured their style of processing preferences and answered a questionnaire with demographical questions (age, grade, etc.). In the following week, the students completed the drawing task or the writing task on the Roman Forum. Immediately after completing the task, the students completed the situational interest questionnaire (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. 2010) and the task-related questionnaire. Additionally, we interviewed 16 students. One experimenter (the first author) was present during the intervention (drawing/writing task) and conducted the interviews. The pre-measurements were administered by the students’ regular history teachers, who were all given a manual detailing the instructions to give to their students.

Hypotheses

Due to the lack of previous research on learner-generated representational drawings in secondary history education and because both drawing and writing tasks are believed to enhance information processing, we did not expect to observe differences in historical plausibility. We expected the students in the drawing condition to reproduce less information from the sources and to use more information elements from prior knowledge or from their imagination than students in the writing condition because it was not as easy for students in the drawing condition to directly copy (textual) information. Therefore, we expected them to generate more images of their own. In addition, we expected the students with a stronger preference for visual processing to report higher situational interest in the drawing condition than in the writing condition.

Results

In this section, we report the results of the analysis of the students’ products; the results of the analysis of the effects of type of task, prior knowledge, and style of processing preference; and the findings on the students’ perceptions of the task.

Prior knowledge and style of processing scores

There was no significant difference in the scores for prior knowledge for the drawing (M = 8.71, SD = 4.09) and writing (M = 8.84, SD = 3.61) conditions. There also was no significant difference in the scores for the style of processing preference for the drawing (M = 2.29, SD = .37) and the writing (M = 2.26, SD = .32) conditions. Thus, both conditions are comparable with regard to prior knowledge and style of processing preference.

Analyses of drawings and written accounts

The drawing task was completed by 77 students; the writing task was completed by 74. Of the drawings, 31 were completed in a photo-realistic style, and 46 were done in a schematic/iconic style. The word length of the written accounts varied between 30 and 162 words, with a mean length of 80 (SD = 32). Table 3 shows the results for the amount of reproduced (copied) information and the amount of additional information included in the products (the drawings or written accounts). Using a one-way ANCOVA, we determined the effect of the type of task (drawing versus writing) on the amount of reproduced information. We found a significant effect of the type of task on the amount of reproduction, after controlling for prior knowledge (F(1,139) = 44.27, p = .000). The partial eta-squared (ƞ2 = .24) shows that this is a large effect. The amount of reproduced information in the written accounts was significantly higher than the amount of reproduced information in the drawings. The covariate, prior knowledge, was significantly related to the amount of reproduction (F(1,139) = 4.47, p = .036). Furthermore, we conducted a one-way ANCOVA to assess the effect of the type of task on the amount of additional information included in the product, controlling for prior knowledge. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find a significant effect of the type of task on the amount of additional information. The students who made a drawing did not add more information from prior knowledge or imagination than the students who wrote an account. The covariate, prior knowledge, was significantly related to the amount of additional information in the products (F(1,139) = 29.01, p = .000).

Table 4 shows the results for the historical plausibility of the students’ images of the forum. On average, plausibility was scored between basic (score 1) and intermediate (score 2). The advanced level (score 3) was achieved by 12% of the students in the drawing condition and 20% of the students in the writing condition. In the drawing condition, there was no significant difference in the scores for historical plausibility for the photo-realistic (M = 1.77, SD = .76) and schematic/iconic drawing style (M = 1.54, SD = .62).

Using a two-way ANCOVA, we explored the effect of the type of task (drawing versus writing) and preferred processing style (visual versus verbal) on the historical plausibility of the image of the forum that the students displayed in their drawing or written account, controlling for prior knowledge. In line with our hypothesis, we did not find a main effect of the type of task on the historical plausibility of the students’ images of the forum, after controlling for prior knowledge. We also did not find a main effect of preferred processing style on the historical plausibility of the products, after controlling for prior knowledge. Furthermore, we did not find an interaction effect of the type of task and preferred processing style on the historical plausibility. The covariate, prior knowledge, was significantly related to the historical plausibility of the students’ images of the forum (F(1,126) = 23.03, p = .000).

Situational interest

Table 5 shows the means and standard deviation for the situational interest questionnaire. Using a two-way ANCOVA, we explored the effect of type of task (drawing versus writing) and preferred processing style (visual versus verbal) on the situational interest students reported after completing the task, controlling for prior knowledge. We found a significant main effect of type of task on students’ situational interest after controlling for prior knowledge (F(1,123) = 4.07, p = .046). The partial eta-squared (ƞ2 = .03) shows that this was a small effect. The students who completed the drawing task reported higher situational interest than the students who completed the writing task. We did not find a significant main effect of preferred processing style on students’ situational interest after controlling for prior knowledge. Furthermore, contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find an interaction effect of the type of task and style of processing on students’ situational interest. The drawing task did not trigger a higher level of situational interest for the students with a preference for visual processing than for the students with a preference for verbal processing. The covariate, prior knowledge, was significantly related to the students’ situational interest (F(1,123) = 8.15, p = .005).

Students’ perceptions

We explored the students’ perspectives on the task using the task-related questionnaire and the interviews. The questionnaire the students completed after the task provided some insights into how they worked on the task and their opinions about drawing or writing. As seen in Table 6, the students in the writing condition reported to have used more texts from the given information, while the students in the drawing condition more images (statements 1 and 2). Drawing was considered more difficult (statements 3 and 5). Lastly, an equal number of students would have preferred to do the other task rather than the one they were assigned (statement 4). When prompted to elaborate on the difference between drawing and writing, in the interviews, the students answered about writing in terms of summarizing the sources or reproducing the “correct” sentences from the given information, whereas about drawing they use phrases like “thinking for yourself how the past must have looked like.” For example, a student explains what happens in his head during a drawing task or a writing task as follows: “When drawing, I see pictures in my head, when writing it is just in my head, without seeing pictures or something.” The students’ answers varied regarding whether drawing or writing was a more effective way to learn. Responses included “It depends on the person” and “I was glad I was allowed to draw because I am not good with words, but someone else may be.” Most of the interviewed students commented that drawing was not something they did often in history class, nor was imagining the past, whether in drawing or in writing: “This is thinking about it, and what we normally do is just cramming information in our heads.” Nevertheless, they thought that imagining concrete situations could be helpful “because you remember more when you imagine you are there yourself,” and because “this is about real people and not about the textbook.”

Some of the students in the drawing condition surprised us when they were given the opportunity to elaborate on their drawings. With the students’ explanations, some drawings became clearer. One student talked about his hesitations when drawing a basket at the feet of a street artist. The street artist was present in the given information, so the student knew he could draw him, but there was no information about what the street artist was paid for his performance. The student reasoned that he could not imagine the artist would perform for nothing, so a basket would be in order. As the student was not sure whether the Romans paid in cash, the student decided to draw some fruit in the basket because payment in food seemed the safest option.

In summary, the questionnaire and the interviews show the following tendencies in terms of the students’ perceptions of the task. The students report that they believe drawing is more difficult than writing and that drawing tasks encourages them to think, whereas writing tasks encourage them to copy. Furthermore, the students who completed the drawing task report they focused primarily on the pictures in the given information. The students who completed the writing task reported they mostly used the texts.

Conclusion and discussion

The first research question concerned the effect of the type of task (drawing versus writing) on the information elements, historical plausibility, and situational interest. In line with our expectations, the students in the drawing condition reproduced less information than the students in the writing condition. However, contrary to our expectations, the students in the drawing condition did not include more information from beyond the sources provided (e.g., from prior knowledge or their imagination) in their product than the students in the writing condition. As we expected, the historical plausibility of the image of the forum that the students produced did not differ between the two conditions. The students in the drawing condition reported more situational interest than the students in the writing condition. The second research question concerned the effect of the students’ preferred processing style on the historical plausibility of their products and their situational interest. We found no significant effect of preferred processing style on the historical plausibility of the products or on the students’ situational interest. Finally, contrary to our hypothesis we did not find an interaction effect. Students with a preference for visual processing did not score higher on the situational interest questionnaire than students with a preference for verbal processing.

The students in the writing condition reproduced or copied more information than the students in the drawing condition. An explanation for this finding can be that writing might be a faster process than drawing; adding a just few words can mean adding a great deal of extra information. In our study, the students in both conditions had 20 min to complete their tasks. The pilot showed that in this time most students could complete the task. However, it is possible that this time-limit influenced the amount of information students were able to provide. Additionally, students who made the drawing might have had more difficulty in reproducing some of the information elements in the given texts, for example, the schedule of the day. Similarly, some of the information from the given pictures, such as the stepping stones in the streets, does not appear in the written products. Some students reported that writing tasks encourage them to copy information to complete the task as quickly as possible, whereas a drawing task forces them to think and create their own image. In further research, it would be worth exploring the differences between the amount of information in drawings and written products when the allotted time is longer or unlimited.

In terms of historical plausibility, both the drawings and the written products followed the same pattern: equal numbers of basic and intermediate products and a somewhat smaller number of advanced products. Because the students’ elaboration on their products during the interviews suggested that they had learned a great deal more than was visible in their drawings, it could be worthwhile for teachers to consider using tools such as peer-feedback or whole-class discussions during or following the process of constructing a drawn or written image to increase the products’ level of historical plausibility. For example, in both conditions, a small majority of our students incorporated both buildings and humans. This may not be surprising because the historical topic in question, the Roman Forum, was a busy square. However, almost half of the students presented only buildings or only humans. For teachers aiming to stimulate the construction of a historically plausible image by their students, this might be a matter to address during or after the completion of the task.

More research is needed to investigate whether drawing tasks are more difficult than writing tasks. A large percentage of the students who did the writing task thought the drawing task was more difficult, whereas a small percentage of students who completed the drawing task considered the writing task more difficult. We do not know whether this perception results from students’ fear of not being able to draw well enough (Levstik and Barton 2015; Anning 1999). However, we observed that the style of drawing did not influence the historical plausibility of the drawings. This could be reassuring for both teachers and students.

The students in the drawing condition reported they used the pictures in the given information more than the writing students did, whereas the students in the writing condition reported using the text in the given information more than the students in the drawing condition did. This is in line with the finding of Van Meter and Firetto (2013) that in a drawing task, a student must produce a picture and so begins by looking at the pictures provided. Thus, for a teacher aiming to encourage students to focus on pictures, a drawing task could be helpful. Writing tasks, however, seem to encourage students to concentrate on given texts, as Schmidgall et al. (2018) also found.

Prior knowledge appeared to be an important factor in both conditions. Students with more prior knowledge reproduced more information from the sources in their product, but also added more information from beyond the sources. Furthermore, students with more prior knowledge produced an image of the forum with a higher level of historical plausibility. Finally, students with more prior knowledge reported higher levels of situational interest. Thus, both tasks seemed to enhance the application of prior knowledge.

We should take into account that when we examine the drawings and writings, we only see the finished product. It is possible that not all the images that the task inspired are visible in the drawing (or writing, for that matter). As history education is, generally speaking, a very verbal domain, it would be interesting to see whether making drawings and talking about them evokes the creation of (more) rich images and stories. Further research should explore in more detail the possibility of using drawing as a tool in history education, especially with regard to students elaborating on their drawings.

The students in the drawing condition reported greater situational interest than the students in the writing condition. This is in line with for example Ainsworth et al. (2011) who also mention possible motivational effects of a drawing task. However, contrary to our expectations, we did not find an interaction effect of type of task and preferred processing style on student’s situational interest. We have to take into account that our sample included relatively few students with a strong preference for visual processing. More research with a larger sample of students with a preference for visual processing is needed. Another limitation might be the measurement of preference for verbal and visual processing. The Style of Processing Scale (Childers et al. 1985) is based upon the assumption that people have a preference for either verbal or visual processing, whereas these preferences might not be mutually exclusive (Bagozzi 2008). In addition, some students are more capable of drawing or writing or are more inclined to do so than others. We have begun to explore the influence of visual and verbal learning preferences, but preference and ability are not the same. An interesting subject for further study would be to investigate in more detail the extent to which a students’ actual drawing or writing ability influences his or her construction of concrete images in these kinds of tasks.

All research has limitations and so does this study. First, it was an explorative study with little precedent in the field of history education. The coding of the drawings in particular was a completely original effort. It is possible that other researchers will further refine this coding system. A second limitation of this study is that we did not measure the knowledge the students gained from the task. Although the aim of this task was to create an image, whether students actually acquire knowledge, or are better able to remember characteristics of Roman life over a longer period of time from a drawing task or a writing task is relevant. The third limitation of this study is the choice of participants. Although we worked with a considerable number of students from different schools, all of the participants were approximately 15 years old and in the higher tracks of secondary education. To form more general conclusions that apply to all types of secondary education, more research with other age groups or cognitive levels is necessary. The same applies to the choice of topic. This task addressed a very concrete topic and therefore was relatively simple. Further research could explore whether representational drawings of other, more abstract topics (e.g., colonization or the Enlightenment) work in the same way. The fourth limitation of this study is that we did not measure the students’ actual ability to draw or write. It is possible that gifted writers are better able to perform a writing task and gifted artists a drawing task.

From the literature, we know that teachers might be skeptical about the use of drawing tasks (Levstik and Barton 2015). However, based on the results of this study, we encourage teachers to make an informed choice about using drawing and writing tasks. If a teacher is looking for a task that aims for students to acknowledge sources and reproduce information, a writing task seems to be the best choice. If a teacher aims for students to produce their own image of the past while processing information from sources and prior knowledge a drawing task could also be an option. Additionally, drawing tasks might trigger a higher level of situational interest. The results of this study show that both drawing and writing tasks can enable students to process historical information in a way that results in equally plausible images of the past.

References

Ainsworth, S., Prain, V., & Tytler, R. (2011). Drawing to learn in science. Science, 333(6046), 1096–1097.

Anning, A. (1999). Learning to draw and drawing to learn. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 18(2), 163–172.

Bagozzi, R. (2008). Some insights on visual and verbal processing strategies. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18(4), 258–263.

Boerma, I., Mol, S., & Jolles, J. (2016). Reading pictures for story comprehension requires mental imagery skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1630.

Bos, L. T. (2016). Moving beyond words. Supporting text processing using a situational model approach. PhD-thesis, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Bosschaart, A., Kuiper, W., & Van der Schee, J. (2014). Students' mental models with respect to flood risk. International Review of Geographical and Environmental Education, 24(2), 131–147.

Bronkhorst, L. H., & Akkerman, S. F. (2016). At the boundary of school: continuity and discontinuity in learning across contexts. Educational Research Review, 19, 18–35.

Childers, T., Houston, M., & Heckler, S. (1985). Measurement of individual differences in visual versus verbal information processing. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(2), 125–134.

Cox, R. (1999). Representation construction, externalized cognition and individual differences. Learning and Instruction, 9(4), 343–363.

Cunningham, D. L. (2009). An empirical framework for understanding how teachers conceptualize and cultivate historical empathy in students. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 41(5), 679–709.

Dawson, I. (2009). What time does the tune start?: from thinking about ‘sense of period’ to modelling history at key stage 3. Teaching History, 135, 50–57.

De Koning, B., & Van der Schoot, M. (2013). Becoming part of the story! Refueling the interest in visualization strategies for reading comprehension. Educational Psychology Review, 25(2), 261–287.

De Leur, T., Van Boxtel, C., & Wilschut, A. (2015). ‘Just imagine…’ students’ perspectives on empathy tasks in secondary history education. International Journal of Historical Learning Teaching and Research, 13(1), 69–84.

De Leur, T., Van Boxtel, C., & Wilschut, A. (2017). ‘I saw angry people and broken statues’: historical empathy in secondary history education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(3), 331–352.

Dilek, G. (2010). Visual thinking in teaching history: reading the visual thinking skills of 12 year-old students in Istanbul. Education 3–13, 38(3), 257–227.

Ehrlén, K. (2008). Drawings as representations of children’s conceptions. International Journal of Science Education, 31(1), 41–57.

Epstein, T. (1994). Sometimes a shining moment: high school students’ representations of history through the arts. Social Education, 58(3), 136–141.

Fournier, J., & Wineberg, S. (1997). Picturing the past: gender differences in the depiction of historical figures. American Journal of Education, 105(2), 160–185.

Gobert, J., & Clement, J. (1999). Effects of student-generated diagrams versus student-generated summaries on conceptual understanding of causal and dynamic knowledge in plate tectonics. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36(1), 39–53.

Huijgen, T., Van Boxtel, C., Van der Grift, W., & Holthuis, P. (2014). Testing elementary and secondary school students’ ability to perform historical perspective taking: the constructing of valid and reliable measure instruments. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(4), 653–672.

Husbands, C. (1996). What is history teaching? Language, ideas and meaning in learning about the past. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174.

Lee, P., & Ashby, R. (2000). Progression in historical understanding among students ages 7-14. In P. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history. National and international perspectives. New York, London: New York University Press.

Lévesque, S. (2008). Thinking historically. Educating students for the twenty-first century. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Levstik, L., & Barton, K. (2015). Doing history. New York, London: Routledge.

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Durik, A., Conley, A., Barron, K., Tauer, J., Karabenick, S., & Harackiewicz, J. (2010). Measuring situational interest in academic domains. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(4), 647–671.

Lohse, G., Biolsi, K., Walker, N., & Rueter, H. (1994). A classicfication of visual representations. Communications of the ACM, 37(12), 36–49.

Marcus, A., Metzger, S., Paxton, R., & Stoddard, J. (2010). Teaching history with film. New York: Routledge.

Mayer, R., & Massa, L. (2003). Three facets of visual and verbal learners: cognitive ability, cognitive style, and learning preference. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 833–846.

Plass, J., Chun, D., Mayer, R., & Leutner, D. (1998). Supporting visual and verbal learning preferences in a second-language multimedia learning environment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 25–36.

Prangsma, M., Van Boxtel, C., Kanselaar, G., & Kirschner, P. (2009). Concrete and abstract visualizations in history learning tasks. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(2), 371–387.

Sadoski, M., & Paivio, A. (2013). Imagery and text. A dual coding theory of reading and writing. New York /London: Routledge.

Savenije, G. M., Van Boxtel, C., & Grever, M. (2014). Learning about sensitive history: “heritage” of slavery as a resource. Theory and Research in Social Education, 42(4), 516–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2014.966877.

Schmidgall, S. P., Eitel, A., & Scheiter, K. (2018). Why do learners who draw perform well? Investigating the role of visualization, generation and externalization in learner-generated drawing. Learning and Instruction, 60, 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.01.006.

Schwamborn, A., Mayer, R., Thillmann, H., Leopold, C., & Leutner, D. (2010). Drawing as a generative activity and drawing as a prognostic activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 872–879.

Stein, M., & Power, B. (1996). Putting art on the scientist's palette. In R. S. Hubbard & K. Ernst (Eds.), New entries: learning by writing and drawing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Van Leeuwen, T., & Jewitt, C. (reds.)(2002). Handbook of visual analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Van Meter, P., & Firetto, C. (2013). Cognitive model of drawing construction. Learning through the construction of drawings. In G. J. Schraw, M. T. McCrudden, & D. Robinson (Eds.), Learning through visual displays. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Van Meter, P., & Garner, J. (2005). The promise and practice of learner-generated drawing: literature review and synthesis. Educational Psychology Review, 17(4), 285–325.

Wilschut, A. (2012). Images of time, the role of a historical consciousness of time in learning history. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts. Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Tessa de Leur. Research Institute of Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam and Centre for Applied Research in Education, Faculty of Education, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Nieuwe Achtergracht 127, 1081 WS Amsterdam. E-mail: T.L.deLeur@uva.nl Web site: www.uva.nl; www.hva.nl

Current themes of research:

Historical empathy. Tasks that stimulate historical imagination.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

De Leur, T., Van Boxtel, C. & Wilschut, A. (2017). ‘I saw angry people and broken statues’: historical empathy in secondary history education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65-3, 331-352.

De Leur, T., Van Boxtel, C. & Wilschut, A. (2015). ‘Just imagine…’ Students’ perspectives on empathy tasks in secondary history education. International Journal of Historical Learning Teaching and Research 13:1, 69-84.

Carla van Boxtel. Research Institute of Child Development and Education and Amsterdam School of Historical Studies, University of Amsterdam, Nieuwe Achtergracht 127, 1081 WS Amsterdam. E-mail: C.A.M.vanBoxtel@uva.nl Web site: www.uva.nl

Current themes of research:

The learning and teaching of history. Historical reasoning. The learning of historical concepts. Heritage education. The potential of collaborative learning in small groups and whole-class discussions.

(Selection of) relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Schep, M., van Boxtel, C. A. M., & Noordegraaf, J. J. (2017). Competent museum guides: defining competencies for use in art and history museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 33(1), 2.

de Groot-Reuvekamp, M., Ros, A., van Boxtel, C., & Oort, F. (2017). Primary school pupils’ performances in understanding historical time. Education 3-13, 45(2), 227-242.

Stoel, G. L., van Drie, J. P., & van Boxtel, C. A. M. (2015). Teaching towards historical expertise: developing a pedagogy for fostering causal reasoning in history. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47(1), 49-76.

Huijgen, T., van de Grift, W., van Boxtel, C., & Holthuis, P. (2016). Teaching historical contextualization: the construction of a reliable observation instrument. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(2), 159-181.

Arie Wilschut. Centre for Applied Research in Education, Faculty of Education, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Wibautstraat 2-4, 1091 GM Amsterdam. E-mail: a.h.j.wilschut@hva.nl Webs site: www.hva.nl

Current themes of research:

Relevance of histor. Citizenship education. Bilingual history education.

Relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Oattes, H., Oostdam, R., de Graaff,R., Wilschut, A. (2018). The challenge of balancing content and language: perceptions of Dutch bilingual education history teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 70, 165-174.

Van Straaten, D., Wilschut, A., Oostdam,R. (2018). Measuring students’ appraisals of the relevance of history: the construction and validation of the Relevance of History Measurement Scale (RHMS). Studies in Educational Evaluation, 56, 102-111.

Van Straaten, D., Wilschut, A., Oostdam,R. (2016). Making history relevant to students by connecting the past, present and future: a framework for research. Journal of Curriculum Studies 48;4.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Information leaflet

Life in Ancient Rome

Introduction

Ancient Rome started as a small village near the Tiber River. Between the second century BC and the second century AD, the village of Rome grew into a large city. The big city became a vast empire. At first, the Romans conquered Italy, and later they won the rest of Europe, part of Asia, and North Africa.

Until approximately 50 BC, the Roman Empire was ruled by the Senate: an assembly of old and wealthy Roman men. After a civil war, emperors took their place, but the Senate still existed.

The first emperor, August, organized the empire well. He stimulated trade with the conquered areas, with which the Romans earned a great deal of money. The Romans built aqueducts to provide the people with water and they built theaters and amphitheaters for entertainment. Roads were built to enable the army to move freely through the empire.

The city of Rome was the center of the Roman Empire. More than 1 million people lived in the city: rich and poor Romans and foreigners from all the corners of the empire. In the heart of Rome was the Roman Forum. In this square, trade took place, justice was pronounced, the gods were worshipped, and political decisions were made.

1. The Roman Forum

2. The Forum

The Roman Forum was the most important square in Ancient Rome, situated in the center of the city.

The forum was the place to be, to meet your friends, hear gossip, see improvised performances, and watch lawyers dispute.

At the forum, it was always crowded. In the basilicas, merchants traded and justice was pronounced. The Senate met in the Curia, and the different temples were the religious heart of Rome. For the Roman magistrates, worshipping the Roman gods and being faithful to the Roman Empire went hand in hand.

All the main streets of Rome ended on the forum. Therefore, many people passed the forum at least once a day.

3. Everyone

“At the Forum, you will find all possible kinds of people. There, you can meet whomever you want, good and bad people, decent folks and others.”

(From the play “The Weevil,” written by the Roman poet Plautus)

4. Schedule

For a Roman, the average day was scheduled as follows:

Before sunrise: getting up, putting on a toga or tunic, walking to work or school (men and boys), and working at home or buying groceries (women and girls)

Between 1 and 4 PM: walking back home, siesta (midday rest)

After 4 PM: continuing to work, visiting one of the bath houses, playing outside, going to the theater or amphitheater, or visiting friends

Between 6 and 8 PM: cena (dinner)

Early to bed

5. A drawing of a street in Ancient Rome (reconstruction)

This image was retrieved from: http://members.home.nl/keesdebrouwer/romeinen/06_de_stad.htm.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Leur, T., van Boxtel, C. & Wilschut, A. “When I’m drawing, I see pictures in my head.”: secondary school students constructing an image of the past by means of a drawing task and a writing task. Eur J Psychol Educ 35, 155–175 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00419-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00419-7