Abstract

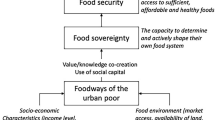

As world food and fuel prices threaten expanding urban populations, there is greater need for the urban poor to have access and claims over how and where food is produced and distributed. This is especially the case in marginalized urban settings where high proportions of the population are food insecure. The global movement for food sovereignty has been one attempt to reclaim rights and participation in the food system and challenge corporate food regimes. However, given its origins from the peasant farmers' movement, La Via Campesina, food sovereignty is often considered a rural issue when increasingly its demands for fair food systems are urban in nature. Through interviews with scholars, urban food activists, non-governmental and grassroots organizations in Oakland and New Orleans in the United States of America, we examine the extent to which food sovereignty has become embedded as a concept, strategy and practice. We consider food sovereignty alongside other dominant US social movements such as food justice, and find that while many organizations do not use the language of food sovereignty explicitly, the motives behind urban food activism are similar across movements as local actors draw on elements of each in practice. Overall, however, because of the different histories, geographic contexts, and relations to state and capital, food justice and food sovereignty differ as strategies and approaches. We conclude that the US urban food sovereignty movement is limited by neoliberal structural contexts that dampen its approach and radical framework. Similarly, we see restrictions on urban food justice movements that are also operating within a broader framework of market neoliberalism. However, we find that food justice was reported as an approach more aligned with the socio-historical context in both cities, due to its origins in broader class and race struggles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The original names of academics interviewed on the concept of food sovereignty in the US have been kept upon permission. Pseudonyms have been given to all other respondents in the Oakland and New Orleans areas.

Similarly, corporate investors are acquiring vast tracts of land in the Global South, particularly in Africa, for timber plantations, food and biofuels production (Lyons et al. 2014).

Interview with Madeleine Fairbairn, New York City, 25 July 2011.

Interview with Raj Patel, San Francisco, 26 July 2011.

La Via Campesina’s website: http://viacampesina.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=27&Itemid=44.

Key informant interview with H. Wittman, 26 July 2011.

Key informant interview with food policy scholar, Oakland, 28 July 2011.

Interview with Alison Alkon, Oakland, 1 August 2011.

Key informant interview with food policy scholar, 28 July 2011.

Phat Beets website: http://www.phatbeetsproduce.org/about/mission-statement/.

Interview with Phat Beets volunteer Sherri Oakes, Oakland, 30 July 2011.

See Alemany Farm website: http://www.alemanyfarm.org.

Interview with Alemany Farm co-manager, Tim Bales, San Francisco, 22 September 2011.

Interview with Alemany Farm co-manager, Tim Bales, San Francisco, 22 September 2011.

Interview with Lisa Palm, Garden for the Environment, San Francisco 2 August 2011.

See Mandela MarketPlace’s website: http://www.mandelamarketplace.org/.

Interview with Nora Pines, Oakland, 3 August 2011.

Interview with Nora Pines, Oakland, 3 August 2011.

Interview with Robert Lohane, New Orleans, 8 August 2011.

Interview with Robert Lohane, New Orleans, 8 August 2011.

NOLA stands for New Orleans, Louisiana.

Interview with Grant Edwards, New Orleans, 8 August 2011.

Interview with Derek Glenn, New Orleans, 31 August 2011.

Holly Grove is a neighborhood garden, market and resource center named after the community it is in.

Interview with Jason Green, New Orleans, 6 August 2011.

Abbreviations

- CSA:

-

Community supported agriculture

- FAO:

-

Food and Agricultural Organization

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- NOLA:

-

New Orleans, Louisiana

- NOFFN:

-

New Orleans Food and Farm Network

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

- USFSA:

-

United States Food Sovereignty Alliance

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alemany Farm. http://www.alemanyfarm.org Accessed 2 October 2011.

Alkon, A., and C.G. McCullen. 2010. Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations…contestations? Antipode 43(4): 937–959.

Alkon, A., and T. Mares. 2012. Food sovereignty in US food movements: Radical visions and neoliberal constraints. Agriculture and Human Values 29(3): 347–359.

Allen, P., M. FitzSimmons, M. Goodman, and K. Warner. 2003. Shifting plates in the agrifood landscape: The tectonics of alternative agrifood initiatives in California. Journal of Rural Studies 19: 61–75.

Bello, W. 2009. The food wars. London: Verso.

Bishaw, A. 2012. Poverty 2010 and 2011: American community survey briefs. United States Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acsbr11-01.pdf. Accessed 26 August 2013.

Bodor, J.N., V.M. Ulmer, L.F. Dunaway, T.A. Farley, and D. Rose. 2010. The rationale behind small food store interventions in low-income urban neighborhoods: Insights from New Orleans. The Journal of Nutrition 140: 1185–1188.

Bondi, L., and N. Laurie. 2005. Working the spaces of neoliberalism: Activism, professionalisation, and incorporation. Antipode 37(3): 393–401.

Bullard, R.D. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class and environmental quality, 3rd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Burch, D., and G. Lawrence. 2009. Towards a third food regime: Behind the transformation. Agriculture and Human Values 26: 267–279.

Burns, R. 2014. Atlanta’s food deserts leave its poorest citizens stranded and struggling. The Guardian. 17 March. http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/mar/17/atlanta-food-deserts-stranded-struggling-survive Accessed 30 March 2014.

Campbell, H. 2009. Breaking new ground in food regime theory: Corporate environmentalism, ecological feedbacks and the ‘food from somewhere’ regime? Agriculture and Human Values 26(4): 309–319.

Campbell, H., and J. Dixon. 2009. Introduction to the special symposium: Reflecting on twenty years of the food regimes approach in agri-food studies. Agriculture and Human Values 26(4): 261–265.

Clapp, J., and E. Helleiner. 2012. Troubled futures? The global food crisis and the politics of agricultural derivatives regulation. Review of International Political Economy 19(2): 181–207.

DuPuis, E.M., and D. Goodman. 2005. Should we go “home” to eat?: Toward a reflexive politics of localism. Journal of Rural Studies 21(3): 359–371.

Fairbairn, M. 2011. Framing transformation: The counter-hegemonic potential of food sovereignty in the U.S. context. Agriculture and Human Values 29(2): 217–230.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2008. The state of food insecurity in the world, high food prices and food security—threats and opportunities. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/i0291e/i0291e00.htm. Accessed 27 September 2011.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2010. The state of food insecurity in the world: Addressing food insecurity in protracted crisis. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1683e/i1683e.pdf. Accessed 27 September 2011.

Friedmann, H. 2009. Discussion: moving food regimes forward: Reflections on symposium essays. Agriculture and Human Values 26: 335–344.

Friedmann, H., and A. McNair. 2008. Whose rules rule? Contested projects to certify ‘local production for distant consumers’. In Transnational agrarian movements: Confronting globalization, ed. S.M. Borras, M. Edelman, and C. Kay, 1–36. Singapore: Blackwell Publishing.

Friedmann, H., and P. McMichael. 1989. Agriculture and the state system: The rise and decline of national agricultures, 1870 to the present. Sociologia Ruralis 24(2): 93–117.

Goodman, D., and M. Watts. 1995. Reconfiguring the rural or fording the divide?: Capitalist restructuring and the global agro-food system. Journal of Peasant Studies 22(1): 1–49.

Goodman, D., and M. Watts. 1997. Agrarian questions: Global appetite, local metabolism: Nature, culture, and industry in fin-de-siècle agro-food systems. In Globalizing food: Agrarian questions and global restructuring, ed. D. Goodman, and M. Watts, 1–32. London: Routledge.

Gottlieb, R., and A. Joshi. 2010. Food justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Guthman, J. 2006. Neoliberalism and the making of food politics in California. Geo-forum 39: 1171–1183.

Holt-Giménez, E., and A. Shattuck. 2011. Food crises, food regimes and food movements. Journal of Peasant Studies 38(1): 109–144.

Holt-Giménez, E., and R. Patel. 2009. Food rebellions!. Oxford: Pambazuka Press.

Holt-Giménez, E., and Y. Wang. 2011. Reform or transformation?: The pivotal role of food justice in the U.S. food movement. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 5(1): 83–102.

Keck, M., and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists beyond borders. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kirkpatrick, S., and V. Tarasuk. 2011. Housing circumstances are associated with household food access among low-income urban families. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 88(2): 284–296.

La Via Campesina. International Peasant’s Movement. http://viacampesina.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=27&Itemid=44. Accessed 20 September 2011.

Lagi, M., Y. Bar-Yam, K.Z. Bertrand, and Y. Bar-Yam. 2011. The food crises: A quantitative model of food prices including speculators and ethanol conversion. London: New England Complex Systems Institute.

Lang, T. 2010. Crisis? What crisis? The normality of the current food crisis. Journal of Agrarian Change 10(1): 87–97.

Lyons, K., C. Richards, and P. Westoby. 2014. The darker side of green: Plantation forestry and carbon violence in Uganda. California, CA: Oakland Institute.

Magdoff, F., and B. Tokar. 2010. Agriculture and food in crisis: Conflict, resistance and renewal. USA: Monthly Review Press.

Mandela Marketplace. http://www.mandelamarketplace.org/. Accessed 5 October 2011.

Mares, T., and A. Alkon. 2012. Mapping the food movement: Inequality and neoliberalism in four food discourses. Environment and Society 2(1): 68–86.

Martine, G., J.M. Guzman, and D. Schensul. 2008. The growing food crisis: Demographic perspectives and conditioners. Food and Agriculture Organization. http://km.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fsn/docs/UNFPAFoodCrisis_DemographicsNov19-versionMarch20.pdf. Accessed 17 September 2011.

Maye, D., L. Holloway, and M. Kneafsey (eds.). 2007. Alternative food geographies: Representation and practice. Oxford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

McClintock, N. 2008. From industrial garden to food desert: Unearthing the root structure of urban agriculture in Oakland, California. ISSI Fellows Working Papers. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley.

McClintock, N. 2014. Radical, reformist, and garden-variety neoliberal: Coming to terms with urban agriculture’s contradictions. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 19(2): 147–171.

McMichael, P. 2005. Global development and the corporate food regime. In New directions in the sociology of global development, eds. F.H. Buttel and P. McMichael, 11, 269–303. Oxford: Emerald Publishing.

McMichael, P. 2009. A food regime genealogy. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1): 139–169.

McMichael, P. 2012. The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. Journal of Peasant Studies 39(3–4): 681–701.

Nyéléni Declaration on food sovereignty. 2007. In Food sovereignty, ed. R. Patel, Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 673–675.

Olopade, D. 2009. Green shoots in New Orleans. The Nation. 21 September. http://www.thenation.com/article/green-shoots-new-orleans?page=0,1. Accessed 30 October 2011.

Patel, R. 2007. Stuffed and starved: Markets, power and the hidden battle for the world’s food system. London, UK: Portobello Books.

Patel, R. 2009. What does food sovereignty look like? Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 663–706.

Peck, J., and A. Tickell. 2002. Neoliberializing space. Antipode 34(3): 380–404.

Phat Beets. 2010. http://www.phatbeetsproduce.org/about/mission-statement/. Accessed 10 October 2010.

Rose, D., J.N. Bodor, C. Swalm, J.C. Rice, T.A. Farley. 2008. Disparities in the food environment in New Orleans and Southern Louisiana. In National Symposium on Race, Place, and the Environment after Katrina, Deep South Center for Environmental Justice at Dillard University; New Orleans, LA.

Sassen, S. 1990. Economic restructuring and the American city. Annual Review of Sociology 16: 465–490.

Schiavioni, C. 2009. The global struggle for food sovereignty: From Nyeleni to New York. Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 682–689.

Smith, N. 2008. Uneven development. Nature, capital and the production of space. Athens, GR: The University of Georgia Press.

Tilly, C. 2004. Social movements, 1768–2004. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

USDA. 2011. Farmers market and local food marketing: Farmers market growth 1994–2011. United States Department of Agriculture. Accessed 14 November 2011.

USDA. 2014. National count of farmers markets directory listings. United States Department of Agriculture. http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=TemplateS&navID=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&leftNav=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&page=WFMFarmersMarketGrowth&description=Farmers%20Market%20Growth&acct=frmrdirmkt. Accessed 28 September 2014.

Weis, T. 2007. The global food economy: The battle for the future of farming. London, UK: Zed Books.

WHO. 2011. United States of America: Health profile. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/gho/countries/usa.pdf. Accessed 14 November 2011.

Winders, B. 2009. The vanishing free market: The formation and spread of the British and US food regimes. Journal of Agrarian Change 9(3): 315–344.

Wittman, H. 2011. Food sovereignty: A new rights framework for food and nature? Environment and Society: Advances in Research, Special Issue on Food 2(1): 87–105.

Wittman, H., A.A. Desmarais, and N. Wiebe (eds.). 2010. Food sovereignty: Reconnecting food, nature and community. Winnipeg: Halifax Publishing.

York, A.M., and D.K. Munroe. 2010. Urban encroachment, forest regrowth and land-use institutions: Does zoning matter? Land Use Policy 27: 471–479.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the time and effort of numerous urban farmers, activists and academics who shared their thoughts on food justice and food sovereignty meanings and practices. Dr Richards also acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP110102299, The New Farm Owners: Finance Companies and the Restructuring of Australian and Global Agriculture. Additional thanks go to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clendenning, J., Dressler, W.H. & Richards, C. Food justice or food sovereignty? Understanding the rise of urban food movements in the USA. Agric Hum Values 33, 165–177 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9625-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9625-8