Abstract

Recent studies have highlighted the efficacy of and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection among people who inject drugs (PWID), however knowledge of real-world applicability is limited. We aimed to quantify the real-world eligibility for HIV-PrEP among HIV-negative PWID in Montreal, Canada (n = 718). Eligibility was calculated according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines and compared to risk of HIV acquisition according to the assessing the risk of contracting HIV (ARCH-IDU) risk screening tool. Over one-third of participants (37%) were eligible for HIV PrEP, with 1/3 of these eligible due to sexual risk alone. Half of participants were considered high risk of HIV acquisition according to ARCH-IDU, but there was poor agreement between the two measures. Although a large proportion of PWID were eligible for HIV-PrEP, better tools that are context- and location-informed are needed to identify PWID at higher risk of HIV acquisition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While services for the prevention of HIV acquisition have been effective at stabilising or reducing HIV incidence overall, there remain certain groups that experience the greatest burden of HIV. In Canada, surveillance data for 2016 show that injection drug use is the second most frequent HIV exposure category, representing 15% of reported HIV cases, behind sexual contact among men who have sex with men (MSM) [1]. Prevention of HIV acquisition remains a priority, with national and international guidelines informing interventions and harm reduction measures for these groups [2, 3]. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) represents one such intervention, in which antiretroviral therapy is provided to HIV-negative individuals to prevent infection. Significant reductions in HIV incidence rates have been demonstrated in men who have sex with men, female sex workers, transgender females, and serodiscordant couples using PrEP [4,5,6]. Among people who inject drugs (PWID), a randomised controlled trial showed a 49% reduction in the incidence of HIV during four years of follow-up that increased to 74% in the most adherent participants [7]. However, little is known about how to identify and target individuals with the greatest risk of HIV acquisition in order to maximise the real-world efficiency of this intervention as part of a spectrum of preventive interventions for PWID [8].

World Health Organisation guidelines recommend HIV PrEP be offered as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV infection, as part of combination HIV prevention [3]. In 2019, the European AIDS Clinical Society recommended HIV PrEP based solely on sexual risk behaviours and failed to consider injection drug use as a risk [9]. Recent Canadian guidelines include injection-related risk factors, but employ specific criteria requiring information of the injection equipment sharing partner that may be difficult to apply in clinic, such as HIV status, HIV viral load or HIV risk [10]. In contrast, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides comprehensive guidelines for PrEP implementation, suggesting that PrEP be offered to PWID reporting injection equipment sharing or to individuals with sexual risk factors in the past 6 months [2]. Initial estimates of nationally representative data in the USA suggested one quarter of sexually active MSM (25%, n = 492000), one fifth of people who inject drugs (19%, n = 115000), and < 1% of heterosexually active adults (n = 624000) would be eligible for PrEP according to CDC guidelines [11]. Identifying PWID at high risk for HIV represents a challenge and few tools exist to assist clinicians in applying existing guidelines.

Besides sharing equipment, other drug injection behaviours—such as cocaine injection and a high frequency of injection—have been identified as strong independent predictors of HIV seroconversion [12,13,14]. Currently, the CDC guidelines only capture a portion of the risk behaviours of importance (i.e. equipment sharing) and it may be necessary to include additional indicators to increase sensitivity. The assessing the risk of contracting HIV (ARCH-IDU) score, a screening tool developed for PWID within the ALIVE cohort (Baltimore, MD), demonstrated a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 43% in predicting HIV seroconversion at the next visit based on seven indicators: age category, current opioid agonist treatment, and five injection-related behaviours [14]. This is the only recent and empirically-derived HIV risk screening tool that addresses risks related to injection drug use, and has been recommended as a clinical tool for assessing PrEP eligibility among PWID both in the literature and in Canadian guidelines [10]. In order to identify PWID most likely to benefit from PrEP, there is a need to evaluate and compare the applicability of a well-known guideline (i.e., CDC) and clinical screening tool, the ARCH-IDU, to guide clinicians.

The aims of this study are (1) to determine the real-world eligibility for HIV PrEP according to the CDC guidelines among a cohort of PWID in Montréal, and (2) to compare CDC PrEP eligibility criteria with ARCH-IDU HIV acquisition risk scores.

Methods

Study Population

The study population was drawn from the Hepatitis Cohort (HEPCO), a prospective cohort study of PWID in Montréal, Canada examining individual and contextual factors associated with HIV and HCV infection since 2004 [15]. Recruitment criteria include being 18 years of age or older, living in Montréal and having injected drugs within the past 6 months. A baseline questionnaire gathers information on socio-demographic characteristics, detailed past and current drug use patterns, and related behaviours in the past 6 months. This questionnaire was adapted from a previously validated instrument [12]. For the purposes of this study, only HIV-negative participants who completed the baseline questionnaire from March 2011–August 2017 were included. Limiting participants to this timeframe was done to assure an analytical sample reflecting the current substance using and harm reduction context [e.g., opioid agonist therapy (OAT) and needle-syringe access]. Participants who had unknown HIV status at baseline were included if they were confirmed HIV negative at the next follow up visit. All participants received a small stipend (CAD$15–20), and provided informed consent in compliance with the institutional review board of the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board of the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (reference: 17.096) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Measures

The primary outcome of this study was eligibility for PrEP at baseline defined by the CDC guidelines indications for PrEP. The CDC criteria are based on several demographic and behavioural indicators that vary based on the risk population being considered [2]. Among all PWID, PrEP is recommended for those who report injection equipment sharing in the past 6 months. Additionally, among heterosexually active males and females, PrEP is recommended for those who report (1) a recently diagnosed bacterial STI; (2) an ongoing sexual relationship with an HIV-positive partner; (3) infrequent use of condoms during sex with partner(s) of opposite sex who are known to be at substantial risk of HIV infection; or (4) being a behaviourally bisexual male who self-identifies as heterosexual. For sexually active MSM, any condomless anal sex or a recently diagnosed bacterial STI are considered indication for PrEP.

Items from the baseline questionnaire were selected in order to create variables representing CDC eligibility criteria, with slight modifications as necessary. Participants were considered eligible for PrEP if they met at least one criterion at enrolment. Because information regarding ‘partner(s) of opposite sex who are known to be at substantial risk of HIV infection’ was limited, heterosexual men and women were considered to have met this criterion if reporting (1) sex with at least one person who injects drugs, and (2) any infrequent condom use during vaginal or anal sex in the past month. Second, information regarding condom use was assessed for the past month only (compared to the time frame used in the CDC guidelines; past 6 months). Finally, the criteria ‘ongoing sexual relationship with an HIV-positive partner’ was considered as met if participants reported vaginal, oral, or anal sexual activity with ≥ 1 HIV-positive partner in the past month. All other criteria were drawn directly from the questionnaire, as described in Table 2.

For comparison, ARCH-IDU risk scores were calculated for each participant [14]. This brief screening tool allocates a specific score to each category related to (1) age, (2) current OAT enrolment, and (3) a composite injection score comprising recent heroin injection, cocaine injection, cooker sharing, needle-syringe sharing, and visit to shooting gallery (item scores detailed in Table 3). Thereafter, the scores for each item are summed and a cumulative score out of 100 points is generated. In the validation by Smith et al., a score of ≥ 46 was considered high risk for HIV seroconversion, with a sensitivity (i.e., becoming HIV-positive at the next study visit) of 86.2% and a specificity (i.e. remaining HIV-negative at the next study visit) of 42.5%. The same score threshold for high risk was applied in the current study.

Analysis

The proportion of participants considered at high risk for HIV acquisition based on ARCH-IDU was compared to CDC guideline criteria. Agreement between the two measures was assessed using (1) the Cohen’s κ coefficient [difference between observed and chance agreement as a fraction of the maximum difference (one minus chance agreement)], and (2) the Chamberlain’s percent positive agreement (number of individuals both high risk according to ARCH-IDU and eligible according to CDC out of the total number of individuals eligible for at least one of the measures) and percent negative agreement (number of individuals both not high risk according to ARCH-IDU and not eligible according to CDC guidelines out of the total number of individuals not eligible for at least one measure) [16]. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC).

Results

Between March 2011 and August 2017, 761 participants completed the baseline questionnaire, of which 43 were HIV positive and thus excluded from the study. The remaining 718 participants were included in this analysis. Most participants were male (81.3%, n = 584), with a median age of 36 years (IQR: 28.2–43.6) (Table 1). A minority of participants (11.6%) identified as gay or bisexual, and 5.4% of males reported sex with another man in the past 6 months. Sexually active participants reported a median of one sexual partner in the last 6 months. While 35% of participants reported receiving OAT in the last 6 months, 40.3% and 42.9% of participants reported injecting heroin and prescription opioids, respectively, in the last 6 months. Females tended to be younger and more often identified as gay/bisexual, but less likely to report recent incarceration and unstable housing. Additionally, females were less likely to report recent cocaine injection and more likely to report OAT receipt or recent heroin injection.

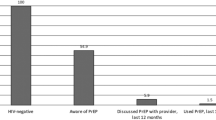

A total of 263 (36.6%) participants were considered eligible for PrEP according to the CDC guidelines (Table 2), of which 184 (25.7%) met the criteria of sharing injection equipment in the last 6 months. Heterosexual risk behaviour was reported for one fifth of participants (n = 142; 19.8%), including an additional 73 that were not eligible based on injecting risk behaviour. Eligibility according to bacterial STI or condomless anal sex among MSM, and bacterial STI, ongoing relationship with an HIV-positive partner, or behaviourally bisexual male among heterosexuals was less frequently reported. Females were more likely than males to be eligible for HIV PrEP according to CDC guidelines (55.2% vs 32.4%), likely driven by higher prevalence of shared injection equipment (35.1% vs 23.5%) and infrequently used condom with 1 or more partners of unknown HIV status (55.0% vs 19.0%) (Table 2). Figure 1 illustrates the overlapping proportions of participants meeting each CDC eligibility risk groups for all participants.

Half of the participants (n = 366, 51%) were considered high risk for HIV acquisition according to the ARCH-IDU protocol, with no difference according to gender (49.5% vs 57.5% for males and females, respectively) (Table 3). Of the participants considered eligible for HIV PrEP according to CDC guidelines, 71.9% were considered high risk according to ARCH-IDU, whereas 38.9% of participants considered not eligible for HIV PrEP were considered high risk according to ARCH-IDU (Table 4). Similar outcomes were observed for both males and females (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which separately presents data for males and females).

There were substantial differences in participant characteristics according to their eligibility for HIV PrEP and risk for HIV acquisition (Table 1). Overall, participants that were both high risk for HIV acquisition and eligible for PrEP tended to be younger, were more likely to be female, identify as gay/bisexual, and recently inject cocaine, heroin, prescription opioid or amphetamine. Less frequent current OAT and younger age in the ‘ARCH-IDU only’ and ‘Both’ groups likely reflect the high score allocated to these variable outcomes in the ARCH-IDU screening tool. Stratified analyses revealed similar trends in age distribution, the proportion of respondents reporting sexual minority status, and substances consumed for both males and females separately. Furthermore, difference in recent incarceration was observed across the groups for males (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which separately presents data for males and females). Among males, higher prevalence of gay/bisexual identity in the ‘CDC only’ and ‘Both’ categories likely reflects the condomless anal intercourse inclusion criteria in the CDC guidelines.

Discussion

The efficacy of PrEP to reduce HIV incidence has not been extensively studied in the population of PWID [7], and indication for its use in real-life settings is still not well established. This study examined HIV PrEP eligibility among a cohort of PWID, and the concordance of CDC guideline criteria and the ARCH-IDU risk score among participants recruited from community-based settings in Montréal, Canada, between 2011 and 2017. Just over one-third of participants were considered eligible for PrEP using CDC guidelines and half were considered at high risk for HIV seroconversion when assessed by the ARCH-IDU score. While the CDC guidelines were predominantly based on sexual risk behaviours—with syringe sharing as the only injecting variable—the ARCH-IDU screening tool incorporated factors related to injection drug use but not sexual behaviours, as they were not retained in the risk prediction model of the initial study. Moreover, the two sets of criteria had only poor to fair agreement, highlighting the heterogeneous nature of current tools to guide clinicians in identifying PWID who would benefit from PrEP in addition to other existing prevention measures.

According to a US national survey, CDC estimated that 19% of PWID would be eligible for PrEP according to their guidelines [11]. Very few studies have determined real-world eligibility among PWID populations. Recently, using the CDC guidelines, Roth et al. found that 89.9% of PWID visiting a syringe exchange program in New Jersey were eligible for HIV PrEP [17]. The authors did not specify the prevalence of individual indicators for HIV PrEP eligibility but reported syringe sharing or syringe-mediated drug sharing in 45% of participants, compared to the 25% injecting equipment sharing seen in the current study. This suggests that eligibility for PrEP may vary widely among different PWID populations and that sharing injection equipment is likely not the only factor to consider when assessing need for HIV PrEP. In the CDC survey, an estimated 25% of MSM and 0.4% of heterosexuals would be eligible for PrEP, however there were no estimated for overlapping populations [11]. The proportion of eligible MSM in the current study (31%) was similar to this estimation, however a greater proportion of heterosexual men and women were eligible (33%) by meeting the sexual-risk criteria, illustrating the variety of risks at play in PWID populations.

Few tools exist to evaluate HIV risk of seroconversion among PWID. No study to our knowledge has evaluated real-world HIV risk using ARCH-IDU in relation to PrEP eligibility. In this cohort, one quarter of the participants were considered at high risk based on ARCH-IDU but not eligible for PrEP according to the CDC guidelines. Although ARCH-IDU assesses a subset of injecting behaviours otherwise unaddressed by the CDC guidelines, its development was based on data prior to widespread opioid epidemics and specific to the ALIVE cohort (Baltimore, Maryland) [14]. As injection behaviours and drug epidemics vary from one region to another, developing a screening tool that universally assesses individual HIV risk may be challenging. In ARCH-IDU, the score attributed to each item may be too sensitive or inclusive, contributing to its lack of specificity. In addition, only a small number of injection behaviours were considered in the development of this instrument. Other items, such as frequency of injecting and sharing behaviours (e.g. washes, backloading, and frontloading), could also be considered when assessing PWID HIV risk [18]. Although ARCH-IDU included sexual risk factors in its initial development—but not infrequent condom use and HIV status of sexual partners—these variables were not included in the final risk prediction model and therefore may not be applicable in other settings [14]. The interplay between drug use and sexual behaviors is complex. Evidence shows that people who inject drugs report low levels of condom use and are at higher risk for the sexual transmission of HIV [19, 20]. As such, ARCH-IDU may exclude an important proportion of PWID at risk sexually for HIV but identified using CDC criteria.

Provision of PrEP should be part of a spectrum of preventive interventions and complimentary to existing harm reduction measures. PrEP prescription among PWID based on injection risk behaviour remains largely absent [21, 22], largely due to a lack of awareness among PWID [23,24,25]. However once aware, willingness to use PrEP as an additional measure to prevent HIV transmission has been found to be moderate to high across multiple studies [26,27,28]. Barriers to the uptake of PrEP are varied, and include individual (e.g. low PrEP knowledge, limited risk perception, competing needs), interpersonal (e.g. negative interactions with health care providers, HIV-related stigma), clinical (poor infrastructure and capacity for PWID), and structural (e.g. incarceration, homelessness, lack of money or insurance) level determinants [29]. On the other hand, a recent study among PWID participating in OAT programs showed a positive response and good adherence to PrEP when it was integrated into usual care services [30]. Similarly, care providers show varying awareness to PrEP and willingness to prescribe. While infectious disease physicians and those providing HIV-related care reported more knowledge and support for the use of PrEP, awareness and interest in PrEP among the PWID population remains a concern [21, 31,32,33,34,35]. Practical and comprehensive tools to help clinicians properly identify individuals who would benefit PrEP are needed.

Tools like ARCH-IDU might not be suited for a population where HIV transmission and incidence are quite low as it could lead to an over-prescription of PrEP, possibly affecting the funding of other preventive measures. Identifying people at most risk is crucial to assure cost effectiveness of PrEP among PWID. According to recent mathematical modeling studies, identifying high-risk PWID seems to be a good strategy to improve the cost effectiveness [36]. To do so, we need context-specific strategies and practical instruments to identify high-risk individuals and provide PrEP to ensure the greatest impact on HIV transmission.

This study has limitations. Using data from a Montréal PWID cohort from 2011 to 2017, injecting behaviours and the drugs used in Montréal may differ from other populations and the current situation. Since Quebec’s HIV incidence is fairly low compared to other cities, CDC PrEP eligibility and ARCH-IDU may have overestimated the size of the population at high risk for HIV acquisition in Montréal. In this study, all participants reporting a sexual partner who injects drugs were considered as not meeting the “monogamous partnership with a person recently tested HIV-negative” requirement since information about the sexual partner was in part limited. To address the CDC definition of sex with partner of unknown HIV status who are known to be at substantial risk of HIV infection, participants were included if they reported condomless vaginal or anal sex with a person who injects drugs, and any infrequent condom use during vaginal or anal sex in the past month. This may have incorrectly resulted in increased eligibility if condom use differed depending on whether sex partners injected drugs or not, or, conversely, in decreased eligibility because only the last month was considered. Canadian guidelines and Quebec INSPQ recommendations were not used in this study due to the lack of information regarding injecting and sexual partners in the cohort questionnaires. Nonetheless their recommendations regarding PWID were also limited to sharing injection equipment. However, Canadian guidelines do recommend the use of ARCH-IDU as a screening tool for PrEP.

Conclusion

Better tools are needed to identify PWID at higher risk of HIV acquisition. In light of recent outbreaks of HIV among people who inject drugs in North America, best clinical practice may include utilization of multiple tools to identify individuals at risk of HIV acquisition and assessing the potential benefit of PrEP for PWID. ARCH-IDU lacks specificity and is probably not suitable for all drug-using contexts and could lead to the over-prescription of PrEP in settings with low incidence. And while CDC guidelines offer a reasonable evaluation of sexual risk, this may not be optimal when addressing certain PWID populations. HIV PrEP for PWID could be an important part of harm reduction services but should not replace existing proven interventions. Whether to use PrEP among PWID populations is a clinical decision that remains to be fully informed and determined. Until the knowledge base is sufficiently developed, available guidelines and tools, while imperfect, offer some guidance.

References

Jonah L, Bourgeois AC, Edmunds M, Awan A, Varsaneux O, Siu W. AIDS in Canada—surveillance report, 2016. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2016;43(12):257–61.

Centers for Disease Control. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States—2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. Altanta: Centers for Disease Control; 2017.

World Health Organisation. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Nikolopoulos GK, Christaki E, Paraskevis D, Bonovas S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: evidence and perspectives. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(18):2579–91.

Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410.

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99.

Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90.

Kaplan EH, Merson MH. Allocating HIV-prevention resources: balancing efficiency and equity. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1905–7.

European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS guidelines version 10.0. Brussels: European AIDS Clinical Society; 2019.

Tan DHS, Hull MW, Yoong D, Tremblay C, O’Byrne P, Thomas R, et al. Canadian guideline on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189(47):E1448–E14581458.

Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, Stryker JE, Hall HI, Prejean J, et al. Vital signs: estimated percentages and numbers of adults with indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(46):1291–5.

Bruneau J, Daniel M, Abrahamowicz M, Zang G, Lamothe F, Vincelette J. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus incidence and risk behavior among injection drug users in montreal, Canada: a 16-year longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1049–58.

Boileau C, Bruneau J, Al-Nachawati H, Lamothe F, Vincelette J. A prognostic model for HIV seroconversion among injection drug users as a tool for stratification in clinical trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):489–95.

Smith DK, Pan Y, Rose CE, Pals SL, Mehta SH, Kirk GD, et al. A brief screening tool to assess the risk of contracting HIV infection among active injection drug users. J Addict Med. 2015;9(3):226–32.

Artenie AA, Roy E, Zang G, Jutras-Aswad D, Bamvita JM, Puzhko S, et al. Hepatitis C virus seroconversion among persons who inject drugs in relation to primary care physician visiting: the potential role of primary healthcare in a combined approach to hepatitis C prevention. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):970–5.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Medica. 2012;22(3):276–82.

Roth AM, Aumaier BL, Felsher MA, Welles SL, Martinez-Donate AP, Chavis M, et al. An exploration of factors impacting preexposure prophylaxis eligibility and access among syringe exchange users. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(4):217–21.

Public Health Agency of Canada. HIV transmission risk: a summary of evidence. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2012.

Kapadia F, Latka MH, Hudson SM, Golub ET, Campbell JV, Bailey S, et al. Correlates of consistent condom use with main partners by partnership patterns among young adult male injection drug users from five US cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(Suppl 1):S56–63.

Li J, Liu H, Li J, Luo J, Jarlais DD, Koram N. Role of sexual transmission of HIV among young noninjection and injection opiate users: a respondent-driven sampling study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(12):1161–6.

Weiser J, Garg S, Beer L, Skarbinski J. Prescribing of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pre-exposure prophylaxis by HIV medical providers in the United States, 2013–2014. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):ofx3.

Hull M, Tan D. Setting the stage for expanding HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use in Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2017;43(12):272–8.

Bazzi AR, Biancarelli DL, Childs E, Drainoni M-L, Edeza A, Salhaney P, et al. Limited knowledge and mixed interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(12):529–37.

Roth A, Tran N, Piecara B, Welles S, Shinefeld J, Brady K. Factors associated with awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among persons who inject drugs in Philadelphia: national HIV behavioral surveillance, 2015. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1833–40.

Sherman SG, Schneider KE, Park JN, Allen ST, Hunt D, Chaulk CP, et al. PrEP awareness, eligibility, and interest among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;195:148–55.

Shrestha R, Karki P, Altice FL, Huedo-Medina TB, Meyer JP, Madden L, et al. Correlates of willingness to initiate pre-exposure prophylaxis and anticipation of practicing safer drug- and sex-related behaviors among high-risk drug users on methadone treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173(Supplement C):107–16.

Stein M, Thurmond P, Bailey G. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among opiate users. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1694–700.

Koechlin FM, Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, O’Reilly KR, Baggaley R, Grant RM, et al. Values and preferences on the use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among multiple populations: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1325–35.

Biello KB, Bazzi AR, Mimiaga MJ, Biancarelli DL, Edeza A, Salhaney P, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization and related intervention needs among people who inject drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):55.

Shrestha R, Copenhaver M. Exploring the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among high-risk people who use drugs in treatment. Front Public Health. 2018;6:195.

Wood BR, McMahan VM, Naismith K, Stockton JB, Delaney LA, Stekler JD. Knowledge, practices, and barriers to HIV preexposure prophylaxis prescribing among Washington state medical providers. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(7):452–8.

Smith DK, Mendoza MCB, Stryker JE, Rose CE. PrEP awareness and attitudes in a national survey of primary care clinicians in the United States, 2009–2015. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0156592.

Mullins TLK, Zimet G, Lally M, Xu J, Thornton S, Kahn JA. HIV care providers' intentions to prescribe and actual prescription of pre-exposure prophylaxis to at-risk adolescents and adults. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(12):504–16.

Adams LM, Balderson BH. HIV providers’ likelihood to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention differs by patient type: a short report. AIDS Care. 2016;28(9):1154–8.

Edelman EJ, Moore BA, Calabrese SK, Berkenblit G, Cunningham C, Patel V, et al. Primary care physicians’ willingness to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1025–33.

Fu R, Owens DK, Brandeau ML. Cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for provision of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS. 2018;32(5):663–72.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rachel Bouchard, Élisabeth Deschênes, Marie-Eve Turcotte, Maryse Beaulieu, and the other staff working at the HEPCO research site. We also thank the study participants; without them, this research would not be possible. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research [(CIHR), Grants MOP135260, MOP210232]; the Réseau SIDA et Maladies Infectieuses du Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé [(FRQ-S), Grant FRSQ5227], and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH NIDA, Grant 1R01DA045713-01). B.J. is supported through FRQ-S and CanHepC post-doctoral fellowships. S.H. is supported through a CanHepC postdoctoral fellowship. E.R. holds the chair in addiction research funded by the Charles LeMoyne Hospital Foundation, and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of Université de Sherbrooke.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Julie Bruneau received advisor fees from Gilead Sciences and Merck and a research grant from Gilead Sciences, outside of this current work. Joseph Cox has received advisory fees, honoraria, and research funds from Gilead Sciences, Merck and ViiV. The authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Picard, J., Jacka, B., Høj, S. et al. Real-World Eligibility for HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among People Who Inject Drugs. AIDS Behav 24, 2400–2408 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02800-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02800-w