Abstract

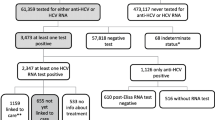

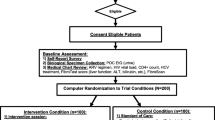

This study describes the self-reported prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection and the HCV care continuum among persons enrolled in the St PETER HIV Study, a randomized controlled trial of medications for smoking and alcohol cessation in HIV-positive heavy drinkers and smokers in St. Petersburg, Russia. Baseline health questionnaire data were used to calculate proportions and 95% confidence intervals for self-reported steps along the HCV continuum of care. The cohort included 399 HIV-positive persons, of whom 387 [97.0% (95% CI 95.3–98.7%)] reported a prior HCV test and 315 [78.9% (95% CI 74.9–82.9%)] reported a prior diagnosis of HCV. Among those reporting a diagnosis of HCV, 43 [13.7% (95% CI 9.9–17.4%)] had received treatment for HCV, and 31 [9.8% (95% CI 6.6–13.1%)] had been cured. Despite frequent HCV testing in this HIV-positive Russian cohort, the proportion reporting prior effective HCV treatment was strikingly low. Increased efforts are needed to scale-up HCV treatment among HIV-positive Russians in St. Petersburg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

There is no associated public data repository for this study.

References

UNAIDS DATA. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2018. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2020.

Tsui JI, Ko SC, Krupitsky E, et al. Insights on the Russian HCV care cascade: minimal HCV treatment for HIV/HCV co-infected PWID in St Petersburg. Hepatol Med Policy. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41124-016-0020-x.

Krupitsky E, Zvartau E, Woody G. Use of naltrexone to treat opioid addiction in a country in which methadone and buprenorphine are not available. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(5):448–53.

Larney S, Leung J, Grebely J, et al. Global systematic review and ecological analysis of HIV in people who inject drugs: national population sizes and factors associated with HIV prevalence. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;77:102656.

Niccolai LM, Toussova OV, Verevochkin SV, Barbour R, Heimer R, Kozlov AP. High HIV prevalence, suboptimal HIV testing, and low knowledge of HIV-positive serostatus among injection drug users in St. Petersburg Russia. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):932–41.

Eritsyan K, Heimer R, Barbour R, et al. Individual-level, network-level and city-level factors associated with HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs in eight Russian cities: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6):e002645.

Heimer R, Usacheva N, Barbour R, Niccolai LM, Uusküla A, Levina OS. Engagement in HIV care and its correlates among people who inject drugs in St Petersburg, Russian Federation and Kohtla-Järve Estonia. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1421–31.

Rhodes T, Platt L, Maximova S, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C and syphilis among injecting drug users in Russia: a multi-city study. Addiction. 2006;101(2):252–66.

Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–83.

Heimer R, Eritsyan K, Barbour R, Levina OS. Hepatitis C virus seroprevalence among people who inject drugs and factors associated with infection in eight Russian cities. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(Suppl 6):S12.

Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, et al. Elbasvir-Grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):625–34.

Hajarizadeh B, Cunningham EB, Reid H, Law M, Dore GJ, Grebely J. Direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C among people who use or inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet GastroenterolHepatol. 2018;3(11):754–67.

Morris L, Smirnov A, Kvassay A, et al. Initial outcomes of integrated community-based hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: findings from the Queensland injectors’ health network. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:216–20.

Elsherif O, Bannan C, Keating S, McKiernan S, Bergin C, Norris S. Outcomes from a large 10 year hepatitis C treatment programme in people who inject drugs: No effect of recent or former injecting drug use on treatment adherence or therapeutic response. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0178398.

American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. 2019. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/. Accessed 13 Feb 2020.

Guidelines for the care and treatment of persons diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273174/9789241550345-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 14 Apr 2020.

Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021: Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246177/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 14 Apr 2020.

Global Hepatitis Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255016/9789241565455-eng.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2020.

Drinking Levels Defined: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al. New data from the addiction severity index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J NervMent Dis. 1985;173(7):412–23.

National Health Interview Survey (ICPSR 2954). United States department of health and human services, National center for health statistics; 1997.

Sobell L, Sobell M. Alcohol timeline followback (TLFB) users’ manual. Toronto: Alcohol Research Foundation; 1995.

Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. Audit The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Guidelines for use in primary care; 2001.

Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the timeline followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(1):154–62.

Sobell L, Sobell M, Buchan G, et al. Timeline Followback Method (Drugs, Cigarettes, and Marijuana); 1996.

Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient care committee & adherence working group of the outcomes committee of the adult AIDS clinical trials group (AACTG). AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–66.

Weatherby N, Needle R, Cesari H, et al. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17(4):347–55.

Needle R, Fisher D, Weatherby N, et al. Reliability of self-reported hiv risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9(4):242–50.

Britton PC, Bohnert AS, Wines JD, Conner KR. A procedure that differentiates unintentional from intentional overdose in opioid abusers. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):127–30.

Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of veterans affairs: results from the veterans health study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):626–32.

Miller W. Form 90: A structured assessment interview for drinking and related behaviors: Test manual US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1996.

Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):797–808.

Rhodes T, Platt L, Judd A, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection, HIV co-infection, and associated risk among injecting drug users in Togliatti, Russia. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(11):749–54.

Vickerman P, Hickman M, May M, Kretzschmar M, Wiessing L. Can hepatitis C virus prevalence be used as a measure of injection-related human immunodeficiency virus risk in populations of injecting drug users? Ecol Anal Addict. 2010;105(2):311–8.

Harris M, Rhodes T. Hepatitis C treatment access and uptake for people who inject drugs: a review mapping the role of social factors. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:7.

Perlman DC, Jordan AE, Uuskula A, et al. An international perspective on using opioid substitution treatment to improve hepatitis C prevention and care for people who inject drugs: structural barriers and public health potential. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(11):1056–63.

Luhmann N, Champagnat J, Golovin S, et al. Access to hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs in low and middle income settings: evidence from 5 countries in Eastern Europe and Asia. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(11):1081–7.

Chikovani I, Ompad DC, Uchaneishvili M, et al. On the way to hepatitis C elimination in the Republic of Georgia-barriers and facilitators for people who inject drugs for engaging in the treatment program: a formative qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0216123.

Amele S, Peters L, Sluzhynska M, et al. Establishing a hepatitis C continuum of care among HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected individuals in EuroSIDA. HIV Med. 2019;20(4):264–73.

Peters L, Laut K, Resnati C, et al. Uptake of hepatitis C virus treatment in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients across Europe in the era of direct-acting antivirals. AIDS. 2018;32(14):1995–2004.

Dara M, Ehsani S, Mozalevskis A, et al. Tuberculosis, HIV, and viral hepatitis diagnostics in Eastern Europe and central Asia: high time for integrated and people-centred services. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(2):e47–53.

Lions C, Laroche H, Zaegel-Faucher O, et al. Hepatitis C virus-microelimination program and patient trajectories after hepatitis C virus cure in an outpatient HIV clinical unit. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol. 2019;32(9):1212–21.

Boerekamps A, van den Berk GE, Lauw FN, et al. Declining hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence in Dutch human immunodeficiency virus-positive men who have sex with men after unrestricted access to HCV therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(9):1360–5.

Boerekamps A, Newsum AM, Smit C, et al. High treatment uptake in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients after unrestricted access to direct-acting antivirals in the Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(9):1352–9.

Kracht PAM, Arends JE, van Erpecum KJ, et al. Strategies for achieving viral hepatitis C micro-elimination in the Netherlands. Hepatol Med Policy. 2018;3:12.

Overton K, Clegg J, Pekin F, et al. Outcomes of a nurse-led model of care for hepatitis C assessment and treatment with direct-acting antivirals in the custodial setting. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;72:123–8.

Papaluca T, McDonald L, Craigie A, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C in prisoners using a nurse-led, state-wide model of care. J Hepatol. 2019;7(5):839–46.

Morey S, Hamoodi A, Jones D, et al. Increased diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C in prison by universal offer of testing and use of telemedicine. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(1):101–8.

Bielen R, Stumo SR, Halford R, et al. Harm reduction and viral hepatitis C in European prisons: a cross-sectional survey of 25 countries. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):25.

Bhandari R, Morey S, Hamoodi A, et al. High rate of hepatitis C reinfection following antiviral treatment in the North East England prisons. J Viral Hepat. 2019;27(4):449–52.

Stöver H, Meroueh F, Marco A, et al. Offering HCV treatment to prisoners is an important opportunity: key principles based on policy and practice assessment in Europe. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):30.

Marco A, Roget M, Cervantes M, et al. Comparison of effectiveness and discontinuation of interferon-free therapy for hepatitis C in prison inmates and noninmates. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(11):1280–6.

Jülicher P, Chulanov VP, Pimenov NN, Chirkova E, Yankina A, Galli C. Streamlining the screening cascade for active Hepatitis C in Russia: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0219687.

Barber MJ, Gotham D, Khwairakpam G, Hill A. Price of a hepatitis C cure: cost of production and current prices for direct-acting antivirals in 50 countries. J Virus Erad. 2020;6(3):100001.

Jo Y, Bartholomew TS, Doblecki-Lewis S, et al. Interest in linkage to PrEP among people who inject drugs accessing syringe services; Miami, Florida. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231424.

Barrett S, Goh J, Coughlan B, et al. The natural course of hepatitis C virus infection after 22 years in a unique homogenous cohort: spontaneous viral clearance and chronic HCV infection. Gut. 2001;49(3):423–30.

Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 Suppl):S58-68.

Tsui JI, Williams EC, Green PK, Berry K, Su F, Ioannou GN. Alcohol use and hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes among patients receiving direct antiviral agents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:101–9.

So-Armah K, Freiberg M, Cheng D, et al. Liver fibrosis and accelerated immune dysfunction (immunosenescence) among HIV-infected Russians with heavy alcohol consumption—An observational cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;20(1):1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in support of URBAN ARCH: U01AA020780, U24AA020779, U24AA020778; and by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research [P30AI042853]. M.C. was supported in this work by a training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [5T32DK007742-22]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in support of URBAN ARCH: U01AA020780, U24AA020779, U24AA020778; and by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853). Maria A. Corcorran was supported in this work by a training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5T32DK007742-22). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of this study, the acquisition of data, data analysis, and/or data interpretation. GP performed the data analysis, assisted by DMC; MAC drafted the manuscript and all authors revised it critically. All authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Judith I. Tsui is the site PI for a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded study, which received donated medications from Gilead. She is also the recipient of a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant from NIH/NIDA (R44DA044053; PI: Seiguer/Tsui) in partnership with a health technology company, emocha Mobile Health Inc. Dr. Debbie M. Cheng serves on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board for Janssen Research & Development. All other authors, including first author Dr. Maria A. Corcorran, have no conflicts of interest to declare. No pharmaceutical grants were received in the development of this study.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Boston University Medical Campus and First Pavlov State Medical University of St. Petersburg, Russia.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to enrollment in the St PETER HIV Study. Participants who were unable to provide informed consent were excluded from the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corcorran, M.A., Ludwig-Baron, N., Cheng, D.M. et al. The Hepatitis C Continuum of Care Among HIV-Positive Persons with Heavy Alcohol Use in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav 25, 2533–2541 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03214-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03214-y